Ivory Plaque for furniture, period of King Sargon I (721-725 BCE) allegedly from Nimrud, returned to Iraq from Steinhardt collection, photo DANY.

The legacy of retiring NY District Attorney Cyrus Vance and the future of his anti-antiquities unit, headed by Assistant District Attorney Matthew Bogdanos, is a hot topic in New York.

In December 2021, the antiquities trafficking unit settled its case against 80 year old billionaire, hedge-fund pioneer and philanthropist Michael Steinhardt. Steinhardt agreed to the seizure of 180 antiquities and their return to foreign countries – and to give up antiquities collecting for his lifetime.

The antiquities unit is controversial, in part due to the resources it drains from more direct New York concerns. At the end of his tenure, Vance was already being criticized for having spent nearly $715 million of the District Attorney Office’s funds from asset forfeiture cases, mostly garnered from banks, on a variety of criminal justice programs, leaving a paltry $31 million for the new DA.

Gold Bowl, allegedly from Nimrud, returned to Iraq from Steinhardt collection, photo DANY.

Vance’s alignment with the international antiquities unit was seen by some as beyond his usual responsibilities – others concluded that he relished the national press from art cases. Some in the press have been asking how sending seized assets to foreign countries hostile to U.S. interests benefited New Yorkers.

The new Manhattan District Attorney, Alvin Bragg, says that he wants to focus first on the needs of his New York constituents. He has pledged to be more transparent than his predecessor, to pull back on prosecuting certain offenses, pursue alternatives to incarceration, and to solicit constituent involvement in allocating spending. One of Bragg’s first actions this January, however, was to return a number of seized antiquities to diplomats from Iraq and Libya.

The antiquities trafficking unit.

DA Vance described the unit’s activities in the Steinhardt case Statement of Facts:

“For more than a decade, this Office has conducted extensive criminal investigations into international antiquities trafficking networks that plunder priceless cultural heritage and traffic antiquities into and through New York… These investigations have resulted in the convictions of 11 traffickers and their co-conspirators; the indictment and pending extradition of another 6 traffickers; the seizure of more than 3600 antiquities valued at more than $200 million. As a result, this Office has returned more than 1500 antiquities to the victims of this pillaging—two dozen countries and individuals—around the globe.”

President George W. Bush with recipients of the 2005 National Humanities Medals, Nov. 10, 2005, Colonel Bogdanos stands to the right of the President. White House photo Eric Draper.

Vance’s point man on antiquities trafficking, Assistant District Attorney Matthew Bogdanos had been chasing unscrupulous art thieves for more than a decade before Vance created the special antiquities unit in 2018. A U.S. Marine Corps Reserve Colonel, he had been recalled to active duty after 9/11. He led multi-agency task forces seeking terrorists in Afghanistan and Iraq. Colonel Bogdanos was stationed in Iraq when the Baghdad Museum was looted. He immediately turned to investigating the theft, spending months tracking down and recovering many of its lost objects. He received a National Humanities Medal in 2005 for his services and on his return, wrote a well-received book on his work to recapture the museum’s collections.[1]

Bogdanos is known for his colorful statements about his work; a number of these, together with some surprising admissions – appeared in a recent profile on Bogdanos by investigative reporter Ariel Sabar in The Atlantic magazine, The Tomb Raiders of the Upper East Side. Bogdanos admits that on his return to the US, he invented a job for himself that then existed only in his imagination.[2]

Bogdanos had written in a NY Times Opinion piece:

“…the patina of gentility we usually associate with the world of antiquities has always rested atop a solid core of criminal activity… I will return to the Manhattan district attorney’s office early next year and head the city’s first task force dedicated to investigating and prosecuting antiquities theft and trafficking. We intend to expose those who engage in the illegal trade for what they are: criminals.”[3]

Sabar commented that “a high-ranking official in the Morgenthau administration” told him the antiquities unit “was completely a figment of his own imagination and his self-aggrandizing personality.”[4]

Still, a decade before the special antiquities unit was officially created, Bogdanos was working closely with Agent Brent Easter of Homeland Security Investigations to publicize the evils of the antiquities trade – and to pursue rogue antiquities dealer Subhash Kapoor.

Kapoor inventory group with some distinctive fakes, screenshot from Homeland Security Investigations video.

Subhash Kapoor, formerly a small time dealer of minor objects, appears to have filled the gap left in the Indian antiquities trade after the arrest of Vaman Ghiya in Jaipur in 2003.[5] The case against Kapoor has been ongoing for the last decade in both India and the United States, and has resulted in the return of the largest number of Indian ancient sculptures and other antiquities to India of any investigation.

In 1974, Kapoor, the son of an Indian antique dealer, immigrated to the US, and established a gallery, Art of the Past, selling manuscripts, miniatures, and other Indian antiques. According to Indian law enforcement, around 2005, Kapoor began smuggling ancient sculptures in bronze and stone taken from temple sites in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. A number of temple robbers arrested in the Tamil Nadu region implicated Kapoor as the eventual recipient of their stolen goods via a chain of local dealers.

Outside of India, investigations into Kapoor’s gallery by the office of the New York District Attorney (DANY) were prompted by information shared by his Singapore-based former partner on the Internet in 2010-2011. Then, in October 2011, India’s Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) issued a Red Corner Notice through Interpol; Kapoor was detained at Frankfurt airport, then extradited to India to be held at a prison in Chennai, Tamil Nadu State.

In July 2012, the DANY issued an arrest warrant for Kapoor, charging him with possession of stolen property. Kapoor’s sister, Sareen was arrested and charged with criminal possession of stolen property valued at more than U.S. $1million. Altogether, HSI raided 12 warehouses of Kapoor’s and seized 2,622 miscellaneous artifacts. Hundreds of these artifacts have since been returned to the Government of India. The charges against Kapoor subsequently prompted the voluntary return by U.S. and international museums and private collectors of objects either sold or donated to them by Kapoor.[6]

In India, the case against Kapoor has proceeded very slowly. Although he was arrested in 2012, the first hearing was held five years after he was jailed, in 2016. He is reported to have trouble with fellow inmates, attacked for wasting water at the common tap when washing his clothes.

Sri Lankan bronzes returned from Kapoor investigation. Photo HSI.

On July 7, 2019, a 285-page criminal complaint and arrest warrant was issued against Kapoor by the DANY, charging him with grand larceny, conspiracy, and numerous counts of criminal possession of stolen property.[7] Seven other individuals were also charged in the same warrant with conspiracy and/or criminal possession of stolen property. It is expected that when his Indian case ends, Subhash Kapoor will be extradited from India and the details of his role in the smuggling of international cultural property will be brought to light.

The Kapoor case gave Bogdanos and Easter the opportunity to develop a Robin Hood/Raiders of the Lost Ark narrative in the press. In 2012, Easter received an Investigator/Prosecutor of the Year Award from HSI NY for Operation Mummy’s Curse, which “successfully uncovered and dismantled a cultural-property and money-laundering network based in New York.” Easter was featured in a 2015 short film, The Real-Life Indiana Jones, ESPN Films, on the Kapoor case, alternately hunting down suspect shipments via computer and condoling with grieving Indian villagers.

At the same time, wrote Sabar in The Atlantic, Bogdanos ensured that his Iraq exploits would not be forgotten in a series of “speeches, interviews, and op-eds…” often at museum and academic venues, “promoting the notion that Iraqi insurgents were using the antiquities trade as a major revenue source—“a cash cow”—for terrorism.”

Bogdanos’ and others’ claims that there was a billion or even multi-billion dollar illegal trade in antiquities and that the trade was funding terrorists was debunked in a major analysis by the RAND Corporation, Tracking and Disrupting the Illicit Antiquities Trade with Open-Source Data.

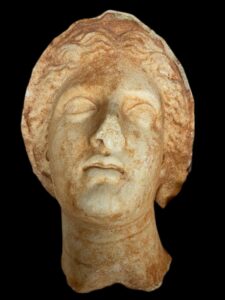

Veiled Head of a Female,” 350 BCE, returned to Libya by new DA Bragg. Photo DANY.

The RAND study identified Bogdanos as among the cultural property activists, bloggers and journalists who have greatly exaggerated the problem of illegal trade. In fact, the RAND report named Bogdanos as a primary source of the widespread but inaccurate belief that antiquities trafficking is linked to trafficking in drugs and weapons.[8]

Not long ago, Bogdanos characterized antiquities dealers as both indifferent to the serious harm looting causes and belonging to “a socio-economic strata that you and I can never hope to attain, with their limousines waiting at the curb and with their bespoke suits.”[9] The description showed a surprising misunderstanding of the working of the antiquities trade, given Bogdanos’ sharp intelligence and familiarity with it.

Of course, criminals should be caught and punished for breaking the law, but Bogdanos’ cases aren’t limited to wrongdoers. Many have involved identifying artworks whose provenance records are unavailable outside law enforcement or objects that were exported long ago from foreign countries and have since passed through the hands of good faith owners.[10] Art dealer associations such as CINOA, the International Association of Dealers in Ancient Art and the UK based Antiquities Dealers’ Association work hard to do due diligence and adhere to ethical standards.

Bogdanos’ sling about “bespoke suits and limousines” was also well off the mark. There are a few very well-heeled dealers (you can count them on one hand). Data on the antiquities market shows that it is the smallest and least valuable section of the global art trade and that most qualify as micro-businesses.[11]

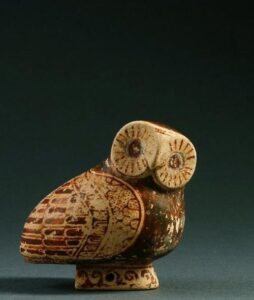

Proto-Corinthian owl figure, 6th C BCE, seized from Steinhardt Collection. Photo DANY.

Bogdanos’ antiquities unit could also be more cautious in its claims about the value of seized antiquities. According to Sabar’s article in The Atlantic, “Bogdanos and his agents have impounded more than 3,600 antiquities, valued at some $200 million.”

Certainly, some of Kapoor’s sales of important Indian bronzes stolen from temples in Tamil Nadu were of high value. However, the DANY’s $100 million dollar list of the items seized from Kapoor appears “greatly inflated.”[12] The Homeland Security Investigations images of the raid on Kapoor’s storage spaces showed numerous objects so obviously fake that museum and other experts who reviewed the footage found it impossible that anyone could take them seriously.[13] Even Indian diplomats have acknowledged as much. It seems that when Kapoor attempted to deceive US Customs by calling his shipments ‘garden statuary,’ he was sometimes not far off the mark. This lack of expert information at the DANY has hopefully been corrected over time.

In 2018, the antiquities trafficking unit was finally officially established: DA Cyrus Vance allocated $2.2 million to it, covering salaries for five years. When the new unit was created, its agenda was clear. Ads placed for ‘antiquities analysts’ stated that the bureau needed staff to provide “critical analysis of records for use in criminal prosecution against trafficking participants such as looters/thieves, smugglers, financiers, shippers, gallery owners, restorers, on-line sites, conservators, auction houses, [and] museum curators…”.[14]

Steinhardt: A major case completed on the eve of Cyrus Vance’s retirement.

The DANY’s antiquities trafficking unit also had targets already in its sights.[15] On January 5, 2018, Bogdanos’ team delivered warrants and seized six objects from the Phoenix Ancient Art gallery and the same day, DANY staff and Homeland Security Investigations agent spent six hours cataloging artworks at the home of Michael Steinhardt. Three years later, after exhaustive research and investigation into sometimes decades of transfers of objects, the District Attorney’s office delivered its results In the Matter of a Grand Jury Investigation into a Private New York Antiquities Collector.

Larnax, chest for human remains from Crete, 1400-1200 BCE. Seized from Steinhardt Collection. Photo DANY.

The Steinhardt case ended with the surrender of 180 objects in early December 2021 from among the approximately 1000 objects he acquired since 1987. The DANY and Steinhardt signed a non-prosecution agreement (the “Agreement”)[16] ending a grand jury probe of Steinhardt and any criminal charges against him. The Agreement also compelled the eighty-year-old billionaire to swear off antiquities collecting for his lifetime.[17]

During the course of the investigation, Bogdanos obtained 17 search warrants for Steinhardt’s antiquities, documents, and digital media. The DANY concluded that 180 of the antiquities in Steinhardt’s possession constituted stolen property under New York law because they were “looted and unlawfully removed from their respective countries.”[18] Some of the objects that will be returned to foreign countries are of spectacular quality, including a magnificent silver and gold rhyton formerly on loan to the Metropolitan Museum that will go to Turkey.

In the Agreement, Steinhardt maintains he did not commit any crimes in buying, selling or dealing in antiquities, while the DA’s office “maintains that the evidence would establish at trial that Steinhardt bought, sold, and otherwise dealt in antiquities and that he knew, or should have ascertained by reasonable inquiry, that the antiquities listed in Exhibit A were stolen.” The lengthy Agreement and Statement of Facts reiterate lists and descriptions of individual objects and their presumed origins, the chain of dealers and collectors that Steinhardt’s acquisitions followed, and the cultural property laws in the countries concerned.[19]

Under the Agreement, Steinhardt will:

- Give up all title to the 180 antiquities and waive all claims against DANY, Homeland Security and any others involved in the seizures;

- Turn over to the DA three pieces now missing from the 180 if they are found;

- Not acquire any more antiquities (defined as artifacts created before 1500 CE) for the remainder of his life; and

- Make no public statement contradicting the provisions of the agreement and obtain DANY permission before making any statement except factual statements in future litigation to which DANY is not a party.[20]

The Ercolano Fresco of the infant Hercules slaying a serpent. Seized from Steinhardt Collection. Photo DANY.

According to the DANY, there was not sufficient evidence of illegality to warrant seizure of other objects owned by Steinhardt.[21] Provided that he does not violate any of the above terms, the District Attorney’s office agreed not to prosecute Steinhardt for any crimes “arising out of his current or prior acquisition, possession, sale, and tax treatment of antiquities.” Regarding Steinhardt’s remaining antiquities collection, numbering approximately 800 pieces, the Agreement states that “DANY takes no position on the legality of the remaining antiquities currently in Steinhardt’s possession, but will not legally challenge the transfer, sale, gift, or bequest of those remaining antiquities.”[22] The Agreement is binding on Steinhardt and the DANY but has no effect on the actions of any other federal, state, or local law enforcement agencies.

Among objects recently seized from American museums: the antiquities collection of a former federal prosecutor.

Other recent announcements of antiquities seizures and returns by the DANY have garnered less press attention, but may have a greater impact on the public, both in New York and elsewhere across the country.

Collector William D. Walsh, a former assistant U.S. attorney who ran narcotic investigations into NY’s waterfront. He was responsible for indicting Vito Genovese, the leader of the Genovese crime family. Later CEO of a venture capital firm, he donated $10 mil. to Fordham’s library together with his antiquities collection.

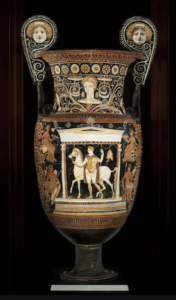

Two hundred ancient objects were returned by the District Attorney to Italy in mid-December 2021. Almost half came from the collection of Fordham University’s Museum of Greek, Etruscan and Roman Art in the Bronx. The museum, which is open free to the public, served as a teaching collection for students and academic researchers. It lost more than one third of its entire collection in the seizure by the DA’s office, including a number of magnificent ceramic vessels. The antiquities had been donated by William D. Walsh, and his wife Jane. Walsh was a Fordham alumnus and himself a former federal prosecutor in NY. The antiquities were displayed in a 4,000 sq ft. section of the Walsh Family Library on the campus, so that books and other reference materials related to the objects were readily accessible to students.

Jennifer Udell, Curator of University Art and the Fordham Museum of Greek, Etruscan, and Roman Art, has described the seizure and return of 99 objects as in the best interest of the museum and the students of the university, giving students insight into “how issues relating to provenance legislation unfold”. In her statement written prior to the return, Dr Udell expressed her hope that after the judge in the case signed a turnover order giving Italy legal possession, Italian authorities would consider the museum’s request to have them back on loan.[23] So far, that has not happened.

Other objects that were returned to Italy in December came from museums outside New York: the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, and the San Antonio Museum of Art in Texas all turned over objects. One returned sculpture was seized from a shipment of antiques purchased in Belgium for the home of Kim Kardashian. The total value of the 200 returned objects was $10 million, an average value of $50,000.

Volute krater, Fordham University Museum, Gift of William D. and Jane Walsh. Credit Fordham University.

Many of the objects were identified as “stolen” because they had been purchased by the Walshes or other collectors from a single Italian art dealer, Eduardo Almagià, a Princeton graduate who lived and did business in New York up until 2003. Almagià is presently living in Italy. Any crimes committed there are too old to be prosecuted under Italian law.

In a phone interview from Italy, Almagià told the NY Times’ Tom Mashberg:

“I sold things from Italy, definitely yes. There are objects in U.S. museums that are undoubtedly stolen from excavations but when they are not objects of the greatest importance, I think they should remain there so they can be appreciated by American visitors…” “There are thousands of items that travel around the world without papers, and they are only asking for papers now, and in the past they never had such requirements,” … “So much money is being spent to persecute dealers when it can be used to repair Italian museums, where so many similar items are already at risk….”

In one thing at least, Almagià is correct. Italy is the second lowest spender in the EU on culture and there are currently millions of uncataloged and unconserved objects in Italian museums.[24]

Aggressive DANY policies and proceedings.

The DANY has been by far the most aggressive prosecutor of alleged antiquities crimes in the United States, taking on numerous cases that federal authorities in the same jurisdiction have not pursued, whether for lack of interest, lack of evidence, or the amount of time that has passed since the alleged crime took place.

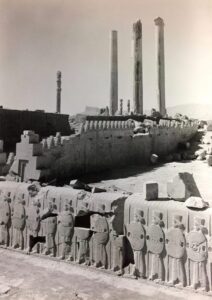

Fragment of a wall frieze from Persepolis, owned for fifty years by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, sold to its insurer, and later seized in New York, then returned to Iran in 2018. Photo: Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

Assistant DA Bogdanos has repeatedly made explicit, both in the Steinhardt Statement of Facts and Agreement and in his correspondence with claimant countries[25] that his position is,

“To prove a suspected crime, all investigations and prosecutions – whether for antiquities trafficking or murder – may also rely on circumstantial evidence. Indeed, New York State criminal law draws no distinction between the weight or importance of direct versus circumstantial evidence in proving a crime.”[26]

What constitutes “sufficient evidence” to show that an object is stolen, in Bogdanos’ view? The Steinhardt Statement of Facts identifies factors the DANY considers indicative of crime. A false statement on an import or export document, for example, is actual, not circumstantial evidence of criminal wrongdoing. People familiar with the art market might not agree that the factors listed by Bogdanos (except #4, depending on the date exported) are indicative of illegality.

According to the Statement of Facts, the “circumstantial evidence” indicating that an object is looted/stolen may include:

- The first documented possessor of the object is a known or convicted smuggler or trafficker of antiquities

- A documented photograph of the object depicts it in a dirty or broken state

- An object is dirty or encrusted

- The find spot or how it was discovered is known or stated in correspondence

- The object was at some time intentionally broken

- An unprovenanced antiquity appears on the international art market for the first time immediately after civil unrest or war in its country of origin

- There is confirmed and specific looting of similar objects at the same time

- The objects are part of a previously unknown hoard

- The object has a false or opaque provenance[27]

Major investment in time and resources.

Among the outside contributors to the Steinhardt case was Christos Tsirogiannis, a forensic archaeologist and dedicated antiquities hunter, who incidentally, had access to the Italian police files that U.S. museums and auction houses were denied. He recently spoke to the Greek Reporter about his work identifying 36 objects in the Steinhardt case. Tsirogiannis described his identification of Steinhardt’s fragmentary Kouros statue valued at about $14 million as “by far a personal best in my career.” Tsirogiannis also told reporter Tasos Kokkinidis that he was disappointed that not a single official in a source country had contacted him “to express thanks or gratitude.” “As usual, everyone wants to take a piece of credit from my work that they don’t deserve,” he said. Tsirogiannis also said that the DANY had two more cases “of the same level” ready to break on which he also worked and identified objects.

Persepolis, area of stolen relief, circa 1933.

The DANY has pursued quite a number of antiquities cases both before and after the anti-trafficking unit was officially organized. Others include:

- The lightning-fast conviction of Japanese art dealer Tatsuzo Kaku under a plea agreement forfeiting a Bhuddapada statue from Pakistan in 2016.

- Two Indian stone statues from the collection of Dr. Avijit Lahiri and his wife Dr. Bratatihi Lahiri were seized by the DANY from Christie’s NY in 2016.

- New York art dealer Nancy Weiner plead guilty in October 2021 to charges of conspiracy and possession of stolen property filed in 2016 for trafficking objects obtained from Subash Kapoor and Douglas Latchford.

- In 2017, the DANY seized a piece of mosaic flooring from the New York home of European antiques dealer, Helen Fioratti, said to have come from the flooring of one of Caligula’s ships, that had been in her home for 45 years.

- Also in 2017, a small piece of a Persepolis frieze valued at $1.2M was seized from a NY art fair and eventually returned to Iran. The theft from Persepolis occurred sometime between 1930 and 1933 and the fragment had been in a Canadian museum for decades.

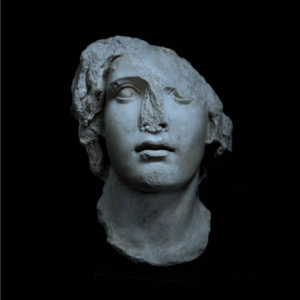

- In 2018, a Head of Alexander was seized from the Safani Gallery that had circulated in known private collections for a least 80 years. The gallery contested the seizure, noting Italy’s complete lack of evidence for its theft. A federal court recently held that Italy was protected from Safani’s lawsuit by foreign sovereign immunity. The case is still pending; the statue’s ownership remains unresolved.

- The Metropolitan Museum in New York agreed to return a gilded coffin to Egypt in 2019 after DANY research indicated it was sold by means of a forged Egyptian export license.

DANY’s policies questioned in NY press.

Head of Alexander the Great as Helios, God of the Sun, c. 300 BCE, courtesy Safani Gallery, Inc.

Recently, Vance and Bogdanos have been castigated in the press for harassing museums and collectors in headline-worthy antiquities cases instead of serving the interests of average New Yorkers. An article in the New York Sun, What Was Cy Vance Doing While Murders Were Soaring on His Watch? was particularly critical of Vance’s anti-antiquities trafficking campaign, noting that the murder rate in Manhattan had nearly tripled since 2018, “while Vance concentrated on the former president’s old tax returns — and playing amateur archaeologist in the arcane world of classical antiquities.”

Noting that the DANY had undertaken joint investigations with law-enforcement authorities in 11 countries: Bulgaria, Egypt, Greece, Iraq, Israel, Italy, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Syria, and Turkey, Stoll wrote:

“If the chemical weapons-using regime in Syria, the Iranian client state in Lebanon, the Hashemite King of Jordan, or the friendlier governments in Israel, Italy, or Egypt want to chase antiques being held by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, or in the hands of private American collectors — well, good luck to them. The statues will not be any safer, or more accessible to scholars, in the hands of the government of the Ba’athist dictator Bashar al-Assad or of Turkey’s Islamist strongman Erdogan than they were at the Metropolitan Museum or under private American ownership.”

He continued, “The ideology undergirding the investigation — with Vance’s talk of “the rights of peoples to their own sacred treasures” — leads to the great museums of New York and London being emptied. What about the rights of peoples not to be gunned down on a Manhattan street corner?”

NY market damaged.

The DANY’s antiquities unit does appear to focus more on ancient art long in the market than on looting today. New cases are much rarer now because dealers and buyers now want to know more about an object’s history.

The antiquities unit appears to have backed off from trying to send offenders to jail. Investigative reporter Ariel Sabar wrote in his Atlantic profile that “proving mens rea, a suspect’s guilty mind, has been harder than Bogdanos imagined.” Bogdanos told him that, “he’s had to reconcile himself to extremely light sentences for some culprits in exchange for testimony against the worst offenders, most of whom have yet to face justice.”

Buddhapada sculpture, footprints of the Buddha. Seized from Japanese art dealer Tatsuzo Taku in 2016.

Whether dealers or collectors go to jail or not, Bogdanos’ willingness to seize objects that he deemed stolen but art dealers and collectors assumed to be legitimate has been enough to seriously damage the antiquities trade in New York, once the largest market in the world and host to the most popular and best attended public fairs for ancient and ethnographic art. If an object is seized, it is both a serious financial loss and a blow to the dealer’s reputation.

Foreign dealers are now wary of bringing objects for sale to New York. Sotheby’s ended its antiquities auctions in NY in 2016 and Christie’s are much reduced. According to reporter Sabar, a study reported that the number of ancient art gallery storefronts in Manhattan had shrunk from a dozen to three, with some dealers operating only by appointment. There do not appear to be any new or younger antiquities dealers in New York.

Steinhardt’s seized antiquities were originally sourced primarily from dealers who have long ago retired. The Steinhardt Statement of Facts states that 169 of the 180 Seized Antiquities prior to his actual acquisition were “trafficked by a total of 12 different criminal smuggling networks” controlled by Giacomo Medici, Giovanni Franco Becchina, Edoardo Almagià, Robin Symes, Robert Hecht, Eugene Alexander, Fritz and Harry Bürki, Gil Chaya, Rafi Brown, Pasquale Camera, George Ortiz, and Noriyoshi Horiuchi.

None of these alleged foreign “controllers of criminal networks” are incarcerated and some have never been charged with crimes. Any cases against them for trafficking in their own countries ended long ago, many without convictions. Italy drops ongoing court cases if they do not end within a certain number of years. The alleged illicit activities took place decades ago and most of the individuals listed are now in their late 70s or 80s – or dead.

Unquestionably, there are many objects that have circulated in the antiquities market that were exported without government permits and in violation of source countries’ laws – their laws on paper, at any rate. Equally unquestionably, objects now deemed ‘stolen’ entered the U.S. legally for decades, but under the Customs rules of the time, were not considered unlawful simply on the basis of foreign export laws. All U.S. Customs asked for for legal importation was accurate descriptions of age and country of origin.

One question for New Yorkers and other Americans today is – should antiquities policy be based on national priorities and defined under federal laws – or should a Manhattan District Attorney’s Office with its own agenda be directing it?

[1] Matthew Bogdanos, Thieves of Baghdad: One Marine’s Passion to Recover the World’s Greatest Stolen Treasures, Macmillan, October 26, 2005. Bogdanos managed the successful return of numerous antiquities to the Iraq Museum.

[2] Although then DA Morgenthau had allowed him to pursue antiquities as part of his work, he had never asked for or gotten approval for a task force. Asked why he’d said this by Sabar, he replied, “You know how when you want something to happen, you say it as if it’s true?” His bosses at that time told Sabar that Bogdanos never presented a viable case. Ariel Sabar, The Tomb Raiders of the Upper East Side, The Atlantic, November 23, 2021, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2021/12/bogdanos-antiquities-new-york/620525/.

[3] Matthew Bogdanos, The Terrorist in the Art Gallery, NY Times, December 10, 2005, https://www.nytimes.com/2005/12/10/opinion/the-terrorist-in-the-art-gallery.html. See also Jason Edward Kaufman, US colonel to lead antiquities anti-theft unit, The Art Newspaper, 31 December, 2005, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2006/01/01/us-colonel-to-lead-antiquities-anti-theft-unit.

[4] Id.

[5] According to police cases filed against Ghiya in his home state of Rajasthan, he illicitly traded in antique sculptures for thirty years, sending some 700 statues to auction via Geneva before finally being arrested in June 2003. Ghiya’s initial conviction was reversed in 2014 by the High Court of Judicature for Rajasthan at Jaipur Bench. In a separate judgement the same day in Vaman Narain Ghiya vs. State of Rajasthan, the High Court of Judicature for Rajasthan overturned Ghiya’s remaining earlier convictions for dishonestly receiving stolen property and habitually dealing in stolen property. Much of the evidence produced at the original trial was held by the High Court to be either inadmissible for lack of proper documentation or to be hearsay. See State of Rajasthan vs. Vaman Narain Ghiya & Anr., (2014) (India) para. 12, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/152498913/. (DB Criminal Appeal No.809/2012, Against The Judgment Dated 20.11.2008 Passed By The Additional Sessions Judge (Fast Track) No.1, Jaipur City, Jaipur IN Sessions Case No..76/2006(141/2003), Judgment January 15, 2014). See Fitz Gibbon Law LLC, Global Art and Heritage Law Series India, Committee for Cultural Policy, 2020, pp 46-48, CCP-Global-Art-and-Heritage-Law-Series-India.pdf.

[6] Fitz Gibbon Law LLC, Global Art and Heritage Law Series India, Committee for Cultural Policy, 2020, pp 49-50, CCP-Global-Art-and-Heritage-Law-Series-India.pdf.

[7] Sarah Cascone, New York Files Charges Against Disgraced Art Dealer Subhash Kapoor in $145 Million Smuggling Ring, Artnet News, July 11, 2019, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/new-york-files-charges-145-million-art-smuggling-ring-1598293

[8] Other sources of claims regarding the size of the antiquities market and its association with terrorism included ATHAR Project’s Katie Paul and the Antiquities Coalition. See Matthew Sargent, James V. Marrone, Alexandra Evans, Bilyana Lilly, Erik Nemeth, Stephen Dalzell, Tracking and Disrupting the Illicit Antiquities Trade with Open-Source Data, RAND Corporation, “The authors [Ed. of a Foreign policy article] quote Danti, who observed that “[t]here is frequently overlap in the smuggling and sale of weapons and antiquities. The two illicit trades, he said, tend to share similar routes, shipments, and dealers.” Although this assumption is widely held among antiquities researchers, there is little evidence to support this conclusion. Most citations supporting this claim refer to a single original source, U.S. Marine Corps Reserve Colonel Matthew Bogdanos’s experiences during the Iraqi Civil War. In fact, evidence from the postings on this channel suggest that there is little overlap of these markets in online platforms.” page 49-50; and “An article in the Wall Street Journal included estimates from Michael Danti, an archaeologist and academic director of ASOR CHI, placing the value of the Islamic State’s antiquities trafficking in the “low tens of millions” annually, while a French security official placed the figure at $100 million. Lehr, of the Antiquities Coalition, estimated that “[c]oming out of Syria, it is $2 billion” and “[w]ith Egypt, it is probably $3–10 billion, globally it has to be a much more significant number.” Id, page 11; and “Our aggregate data suggest that the market for all antiquities, both licit and illicit, is on the order of, at most, a few hundred million dollars annually rather than the billions of dollars claimed in some other estimates … We believe that, going forward, scholars arguing that the illicit market is larger than we suggest here will need to more clearly articulate the means through which these goods are sold.” Id. at page 84-85.

[9] Ben Lewis, What distinguishes an art criminal from a regular crook?, The Art Newspaper, 27 September 2021, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2021/09/27/what-distinguishes-an-art-criminal-from-a-regular-crook.

[10] Italy continues to deny access to information on stolen objects to museums as well as to auction houses and the legitimate art trade, despite the Association of Art Museum Directors, dealer organizations, and auction houses having sought this officially for more than a decade. See Statement of the Association of Art Museum Directors Concerning the Proposed Extension of the Memorandum of Understanding between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of the Republic of Italy Concerning the Imposition of Import Restrictions on Categories of Archaeological Material Representing the Pre-Classical, Classical, and Imperial Roman Periods of Italy, as Amended, Meeting of the Cultural Property Advisory Committee, April 8, 2015, p 10, https://aamd.org/sites/default/files/key-issue/FINAL%20AAMD%20PRESENTATION%202015.pdf

[11] For multiple sources, see Kate Fitz Gibbon, Trade Delivers Reality Check to Money-Laundering Regulators, Cultural Property News, October 30, 2021, https://culturalpropertynews.org/trade-delivers-reality-check-to-money-laundering-regulators/.

[12] Letter from Dr. Stanislaw Czuma, June 2016.

[13] See also The Real Life Indiana Jones, FiveThirtyEight, ESPN Films, a Signals documentary produced and directed by Jason Kohn. This is confirmed in part by Cite to Indian embassy statement about leaving fakes behind.

[14] For hiring information, see https://dany.applicantstack.com/x/detail/a2i2x0xwuww4/aaac

[15] It appears that the DA just happened to be looking into a specific artifact, which led it to Steinhardt, not the other way around. “In February 2017, while investigating a multi-million-dollar marble archaic bull’s head (the “Bull’s Head”) stolen from the archaeological site of Eshmun in Lebanon during the Lebanese Civil War, this Office determined that the Bull’s Head had been purchased by Steinhardt who subsequently loaned it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art (the “Met”).” In the Matter of a Grand Jury Investigation into a Private New York Antiquities Collector, Statement of Facts (hereafter Statement of Facts), Supreme Court New York County, filed December 6, 2021, p 2, https://images.law.com/contrib/content/uploads/documents/292/102693/2021-12-06-Steinhardt-Statement-of-Facts-w-Attachments-Filed.pdf.

[16] In the Matter of a Grand Jury Investigation into a Private New York Antiquities Collector, Agreement (hereafter Agreement), Supreme Court New York County, filed December 6, 2021, https://images.law.com/contrib/content/uploads/documents/292/102693/2021-12-06-Steinhardt-Complete-Agreement-w-Exhibits-Filed.pdf

[17] See Agreement, 4 d., p 2.

[18] Id. at 1.

[19] Note: One dealer who supplied objects to Steinhardt, Svyatoslav Konkin, told the International Association of Dealers in Ancient Art that the Statement of Facts and Agreement contained inaccuracies regarding the provenance and customs entries of objects he sold to Steinhardt. IADAA Newsletter December 2021, January 4, 2022, states, “[the Statement of Facts] also states: “Although Konkin claimed in a letter to Steinhardt that the Gold Bowl “has clear history which goes back at least up to 1970 and earlier, no verifiable provenance prior to Konkin’s 2019 arrival into the United States has ever been identified.” The DA’s media release claims that the bowl was looted from Iraq during its occupation by ISIS, the implication being that this funded terrorism. Konkin says none of this is true and describes the DA’s claims as “fantasy”.”

https://iadaa.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/12-IADAA-Newsletter-December-2021.pdf.

[20] Agreement, 4a-e, p 1-3.

[21] Statement of Facts, p 3.

[22] Agreement, 5b, p 3.

[23] Jennifer Udell, Fordham Museum Helps Resolve Trafficking Case, Fordham Library News, September 1, 2021. https://librarynews.blog.fordham.edu/2021/09/01/fordham-museum-helps-resolve-art-trafficking-case/

[24] Barbie Latza Nadeau, Italy’s Incompetence is Creating New Ruins, Daily Beast, June 04, 2019.

[25] In a letter dated May 29, 2019 to Dr. Khaled El-Enany, Minister of Antiquities of the Arab Republic of Egypt, Bogdanos says, regarding unprovenanced antiquities, “To prove a suspected crime, investigations and prosecutions may also rely on circumstantial evidence. Indeed, New York State criminal law draws no distinction between the weight or importance of direct versus circumstantial evidence in proving a crime. Circumstantial evidence in the case of suspected looted antiquities may include, but is not limited to, the sudden appearance of an object on the market after a source country has been looted of that specific type of object, the first documented photograph of the object depicting it in a dirty or broken state, the existence of inconsistent or demonstrably false provenance for the object, or that the first documented possessor of the object is a smuggler or trafficker of stolen antiquities. Standing alone, any one of these facts may not be sufficient to warrant criminal prosecution. But, when taken together with other evidence, and what may reasonably be inferred from the evidence, such facts are always material, usually probative, and often dispositive.” p 3-4. Bogdanos’ correspondence indicates that even if criminal intent is lacking and a NY owner or seller of an object may not be aware of a source nation’s claim of superior title, civil seizure is justified when there is evidence that an object left an art-source nation after passage of a national patrimony law.

[26] See for example, Agreement, pp 7-8.

[27] Statement of Facts, pp 8-12.

[28] For years, the Italian police have held photographs from the files of members of a previous generation of art dealers who were charged with selling illicitly exported or looted objects. The police have given access to these files to a few academics and researchers as well as other police agencies, who use them to track down artworks when they show up decades later, often after having passed through many hands. See https://culturalpropertynews.org/tsirogiannis-master-of-the-blame-game-goes-after-frieze-masters/

[29] See Statement of the Association of Art Museum Directors Concerning the Proposed Extension of the Memorandum of Understanding between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of the Republic of Italy Concerning the Imposition of Import Restrictions on Categories of Archaeological Material Representing the Pre-Classical, Classical, and Imperial Roman Periods of Italy, as Amended, April 8, 2015, p 5, https://aamd.org/sites/default/files/key-issue/FINAL%20AAMD%20PRESENTATION%202015.pdf.

Assistant DA Matthew Bogdanos, former NY County DA Cyrus Vance and members of the antiquities trafficking unit with seized objects at a press event celebrating their achievements. Credit Office of New York District Attorney.

Assistant DA Matthew Bogdanos, former NY County DA Cyrus Vance and members of the antiquities trafficking unit with seized objects at a press event celebrating their achievements. Credit Office of New York District Attorney.