“The Trump Administration – in its final hours – gifted Turkey the legal rights to claim the vast religious and cultural heritage of the region’s indigenous peoples and minority populations – among them Armenians, Greeks, Assyrians, Chaldeans, Syriacs, Arameans, Maronites, Jews, and Kurds.” Aram Hamparian, Executive Director, ANCA, quoted in an ANCA Press Release, Last Minute U.S.-Turkey Accord Grants Ankara Rights to Christian Cultural Heritage, January 19, 2021.[i]

U.S. Policy to Build a Wall Against the Global Circulation of Art

On June 16, 2021, import restrictions[ii] for a U.S. cultural property agreement with Turkey[iii] came into effect with the issuance of a Designated List of objects prohibited from entry into the United States, covering over a million years of art from Turkey – from 1,200,000 BCE up to 1923. The restrictions bar Mesopotamian, Hittite, Classical, Hellenistic, Byzantine, Seljuk, Ottoman, Greek, Jewish and Armenian art, heirlooms, religious property, and ordinary articles of trade from import into the U.S.

The agreement, in the form of a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between Turkey and the U.S., is the capstone of a U.S. State Department policy to build a wall against the global circulation of art. The MOU with Turkey takes a near-final step toward closing U.S. access to art and artifacts from the Mediterranean world, unless they meet strict documentation requirements that few objects have due to their lengthy circulation – for decades and sometimes for centuries – in the world market.

Chart of Mediterranean by Cavolini, Iconography: winds; cities and flags; shields; Golgotha. Bound in an atlas of six charts. French, highly decorated, unsigned and undated. Date circa 1600, Royal Museums Greenwich catalogue and image metadata.

A few countries remain untethered to this blockade of the Mediterranean region, but the U.S. now has agreements restricting imports of virtually all art without proof of long-ago or lawful export from Morocco, Algeria, Libya, Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Iraq, Turkey, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Greece, and Italy. Tunisian and Albanian requests have been heard by the Cultural Property Advisory Committee at the State Department already. These agreements are both expected – and expected to last.

In fact, these agreements are perpetual for all practical purposes and have already encompassed the globe. Outside of the Mediterranean region, the U.S. has cultural property agreements restricting imports with another thirteen nations,[iv] including most of Central America. Only one agreement has ever lapsed, with Canada, almost 20 years ago. Technically, these agreements are only for 5 years – the time Congress thought it would take to halt a looting emergency and for a requesting country to get its act together. However, they have always been renewed, regardless of the signatory countries’ lack of protection for heritage or performance of the minimal obligations the MOUs seek. Counting both standard bilateral and ‘emergency’ agreements, many have been in place for over 20 years, and a few for 30 years.

Display of antiquities, Izmir Museum of History and Art, Turkey, Photo by Carole Raddato from Frankfurt, 1 April 2015, Germany, CCA-SA 2.0 Generic license.

The approval of ever broader and never-ending 5-year renewals of MOUs make several things clear. First, the Department of State and many of its handpicked appointees to the Cultural Property Advisory Committee (CPAC) are firmly anti-trade and oppose the global circulation of art on principle. The Designated Lists of prohibited imports now routinely include virtually everything ever made within a nation’s borders, including widely circulated antique trade goods and coins, despite the lack of any connection to archaeological looting for the majority of objects.

Second, claims regarding the need for archaeological protection are used to camouflage the State Department’s support for nationalist governments seeking control over both objects and the telling of history. MOUs are signed with authoritarian regimes that have weaponized cultural heritage issues and identity politics to oppress minority populations. Turkey, Egypt, and China are prime examples of dictatorial regimes granted MOUs by the U.S.

And finally, it’s clear that MOUs curtailing entry of art into the United States have proven ineffective to motivate art source countries to do more to protect or preserve archaeological sites. Comprehensive MOUs lasting twenty or even thirty years have failed to solve problems of theft or site destruction inside countries where this occurs.

A Laundry List of Restrictions Covers Sacred Objects and Ordinary Household Goods, Coins and Carpets

Prayer rug, Turkey, Bergama, late 19th century, wool, Huntington Museum of Art, West Virginia, USA. Photo by Daderot, Creative Commons Zero, Public Domain Dedication

The Designated List for Turkey, attached to a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU), was issued June 17, four months after the signing of the MOU on January 19, 2021, the last day of the Trump administration. The Designated List identifies the objects at risk from looting which are prohibited from entry to the U.S. However, instead of blocking imports of objects recently looted from archaeological sites, the new Turkish MOU prohibits U.S. entry to a laundry list of objects, including not only antiquities but also ordinary goods that were made commercially in the hundreds of thousands and which circulated throughout the Ottoman empire and beyond in legal trade.[v]

The list of objects in the Turkish agreement, like all the MOUs signed with Middle East and North African nations, is far more expansive than Congress envisioned under the 1983 Cultural Property Implementation Act, the U.S. legislation authorizing import restrictions. The Turkish agreement covers virtually all handmade objects from the beginning of human occupation, a million years before in the Paleolithic period, up until the establishment of the Turkish state in 1923. The imposition of import restrictions on virtually every single item made throughout human history is clearly contrary to the plain language of the law under which they are made.[vi] The State Department has once again ignored the criteria set by Congress under the CPIA that limit import restrictions to objects actually at risk of current looting and for which the U.S. is a major market nation.

Isnik Bowl, Turkey, 1550-1575, The Museum of Islamic Art, Qatar, Google Art Project.

The so-called ‘archaeological’ materials (up to the 18th century) include not only truly archaeological remains of ancient civilizations but also a far-reaching category of objects deemed religious or ceremonial, including those of Christian and Jewish minorities. The Designated List covers:

Silver coffee pot from Turkey, 19th century, long-term loan to the Honolulu Museum of Art by Doris Duke Foundation for Islamic Art, Photo by Hiart, 2015, Creative Commons Zero, Public Domain Dedication.

“Ceremonial Objects – Ritual and ceremonial objects pertaining to Turkey’s religious communities, in bronze, copper, gold, silver, electrum, iron, and lead. This type includes libation vessels, ritual cauldrons and pitchers, rhytons, masks, chalices, plates, censers, candelabras, crosses, pendants, bells, reliquaries, liturgical spoons, Kiddush cups, book covers and boxes, decorated book spines, Torah pointers, finials, and ampoules.”

Virtually the same objects are also named in the ‘ethnological’ category, with the addition of “prayer beads, icons, amulets, and Bektashi surrender stones,” all the way up to 1923:

“Panel Paintings (Icons)—An icon is a work of art for religious devotion, normally depicting saints, angels, or other religious figures. These are painted on a wooden panel, often for inclusion in a wooden screen (iconostasis), or else painted onto ceramic panels. May be partially covered with gold or silver, sometimes encrusted with precious or semi- precious stone. Approximate date: 4th century A.D. to the 18th century A.D.”

The MOU thus recognizes the Turkish government’s superior rights to those of Jewish, Greek Orthodox, Armenian, and Kurdish religious minorities over their own heritage.

The Designated List also generally covers “material that contributes to the knowledge of the origins, development, and history of the Turkish people,” from the 1st century AD to 1923. The list that follows this general description appears to include every kind of trade good exported throughout the Ottoman Empire and into Europe and elsewhere, even to the coinage used in trade and circulated for centuries!

Bed cover from Turkey, Marash, Armenian, early 20th C, Honolulu Museum of Art, Photo by Hiart, 2015, CCs Zero, Public Domain.

The range of coins on the Designated List is very broad and will significantly limit U.S. collectors and museums from seeking examples of ancient, historic, and pre-20th century coins that circulated in the thousands far beyond Turkey’s present borders. Despite Congress’ explicit statement that import restrictions should apply only to objects that are “first found in” the requesting country; the list instead includes all coins that “that circulated primarily in Turkey,” an impossibly vague standard that impermissibly expands the scope of the U.S. law.

Bindalli (wedding dress) from Turkey, late 19th-early 20th C, Doris Duke Foundation, Photo by Hiart, 2015, CC Zero, Public Domain.

Both the ‘archaeological’ (to 1770) and ‘ethnological” (to 1923) sections include all sorts of “objects of daily use” including “chairs, stools, beds, tables, chests, and desks; kitchen and tableware, book cases, book holders, lecterns, prayer panels, carved diptychs, writing and painting equipment, games, game boxes, combs, clasps, needles, beads, and musical instruments.” The list includes an unspecified variety of textiles, which were the most common Mediterranean trade commodity for centuries, from the medieval to the pre-modern world. These prohibited textiles range from carpets, kilims, and woven and embroidered pillows to fabrics and clothing of linen, wool, cotton, and silk.

All of these objects are available for sale in Turkey’s domestic markets; they are practically an inventory list of goods sold in local bazaars and antique shops across the country. Thus, the Turkish MOU disregards the legal requirement that a U.S. embargo would be efficacious by permitting a requesting nation to sell in its markets the very items it wants to deny to the U.S. market.

Glass and brass lamps, vessels and decorative objects, as well as ceramics and tiles dating up to 1923 are also prohibited entry, despite language in the law stating that import restrictions may only be applied to archaeological artifacts of “cultural significance” “first discovered within” and “subject to the export control” of a specific UNESCO State Party, or to distinctive ethnological materials important to the cultural life of a “non-industrial” society. The Designated List for Turkey fails to heed both the law and the limitations Congress set forth in its 1982 Senate Report.[vii] As the late James Fitzpatrick described the drafting of the CPIA in 2010[viii]:

“Congress spoke of archeological objects as limited to “a narrow range of objects…” [Sen. Report,[ix] p. 4.] Import controls would be applied to “objects of significantly rare archeological stature…”[see Senate Report at 4]

As for ethnological objects, the Senate Committee said it did not intend import controls to extend to trinkets or to other objects that are common or repetitive or essentially alike in material, design, color or other outstanding characteristics with other objects of the same type….”[see Senate Report at 5]

A Diplomatic Plum for an Oppressive Dictatorship and an Insult to U.S. Stakeholders

Kariye Camii aka Chora Church, Istanbul, now converted to a mosque, Anastasis fresco, Paracclesion, July 2007, photo by Gryffindor.

The MOU is a slap in the face to U.S. organizations representing the interests of immigrant communities who have strongly argued against any agreement with the Turkish government. The Turkish agreement is just the latest MOU signed through the Department of State that restricts the rights of oppressed religious minorities to their own heritage. On December 9, 2018, eighteen Jewish organizations sent a letter to U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to protest the inclusion of objects of Jewish heritage in cultural property agreements then being established with Middle Eastern and North African nations.[x] Like the MOU with Turkey, these agreements also included Jewish and Greek and Armenian Christian ritual objects, from antique Torah scrolls to tombstones, books, Bibles and religious writings. Many of the same organizations have voiced strong opposition to the MOU with Turkey.

Greek woman native to Burdur, Turkey. Circa 1870, Photo by Pascal Sébah 1823-1886.

What the Turkish agreement does is to effectively bestows a blessing on President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s hyper-nationalist propaganda and his

blatantly anti-Semitic, anti-Christian, and anti-minority supporters. The Erdoğan government has been unwilling to act to halt demonstrations and false accusations in the media against minorities and has turned a blind eye to the rise of hate speech against non-Muslim faiths.

Religious minority communities are facing increasingly severe prejudice in Turkey. Nonetheless, under this MOU, if Jews, Orthodox Christians, and other religious minorities leave the country, they are unable to take their most precious relics with them. Furthermore, if persons wish to bring artifacts of Turkish origin from any other country into the U.S., they must be able to prove lawful ownership or risk seizure and return of their heritage to the Turkish government.

Overturning Decades of Secular Policy

In 2020, the Erdoğan government converted two major monuments of the Christian faith, Istanbul’s Hagia Sophia and the Chora Church (Kariye Camii), from museums into mosques.[xi] It has since opened Hagia Sofia for Muslim worship. The decision is contrary to Turkey’s secular Constitution and only the latest reconversion by the Erdoğan government of a formerly Christian basilica to use as a mosque. While secularism (laiklik) is enshrined in the Turkish Constitution’s preamble and numerous articles, it is interpreted today as a grant of rights to the state to control religion – not as a guarantee of freedom of religion.[xii] A background study prepared for the European Parliament has well-summarized the links between Turkish domestic political strife and Erdoğan’s Islamizing policies.

Iznik ceramic tiles in Topkapi Palace, photo by Jorge Láscar from Australia, 29 August 2012, CCA 2.0 Generic license.

Erdoğan is using the conversions for explicitly political purposes. He spoke recently of the conversion of Hagia Sophia as gratifying “the spirit of conquest” shown by the capture of Constantinople from the Byzantines in 1453. Erdoğan’s coalition partner, former Deputy Prime Minister and chairman of the Nationalist Movement Party Devlet Bahçeli stated that its conversion was the start of a “new phase” of the Turco-Muslim conquest.[xiii] In August 2020, Imam Ali Erbaş, Turkey’s

head of the Religious Affairs Directorate (Diyanet) gave the first sermon in Hagia Sophia holding a sword. The Imam also used the occasion to state openly that preaching with a sword sends a message about the conversion of Hagia Sophia into a mosque on the one hand and a message of conquest on the other.

When the MOU was announced, Turkey’s Christian minority leaders were pressured to respond with statements of support for the theft of their heritage. Erdoğan’s years of scapegoating and inciting his supporters against minorities have so threatened these vulnerable communities that prelates were compelled to tweet their support for the MOU. This blatant coercion is not surprising, given Erdoğan’s ultranationalist coalition’s emphasis on how Ottoman capitulation to the West was tied to giving civil liberties to religious minorities.[xiv]

Despite the protections assured under the Turkish Constitution, the failure of the Turkish government to grant full legal status to any faith community after almost 100 years has left the non-Muslim and minority religious communities vulnerable to continuing seizures of property and the denial of essential religious and civil rights.

Caravan of 5,000 Christian refugees going from Kharput to Trebizond. circa November 1922, Photographer: C. D. Morris, CCA-SA 2.0 Generic license.

Erdoğan’s Cultural Property Claims are Tied to a Global Political Agenda

Allowing an authoritarian government explicit control of culture can impact international policy in ways the State Department has failed to foresee or acknowledge. In an eye-opening interview with Cultural Property News in September 2020, Elias Gerasoulis, the legislative director of the American Hellenic Institute, explained how Erdoğan has used Turkey’s laws concerning cultural heritage not only to harm its minority religious communities but also to advance a far broader international agenda.

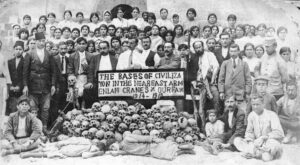

Skulls of Armenians massacred in Urfa, surrounded by Armenian dignitaries and women from the women’s shelter in Urfa’s Monastery of St. Sarkis in June 1919. Wikimedia Commons.

Gerasoulis noted that in September 2020:

“President Erdoğan attacked Israel’s “dirty hand” in his United Nations speech, a blatantly anti-Semitic statement… Erdoğan has talked about seizing Jerusalem and liberating the al-Aqsa mosque. Erdoğan has been condemned by the U.S. State Department for the partnership that he has with Hamas. His own AKP [Ed. The Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi or Justice and Development Party] has talked about the coronavirus being a Jewish conspiracy. I think it is sheer lunacy to give someone who believes anti-Semitic conspiracy theories, who is supporting terrorist groups that organize against Israel, who views himself in the words of his own party as a modern-day Saladin, the twelfth-century conqueror of Jerusalem, to acknowledge his full ownership of Jewish cultural property and heritage, in addition to the cultural property and heritage of other minority groups in Turkey. It should be self-evident why that’s problematic.”

President Barack Obama meeting with Greek Orthodox Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew in Istanbul, 7 April 2009, Photo by Pete Souza, official White House photographer, Public domain.

“There’s a second point, though, which is very important to understand, and that is the geopolitical effect of signing an MOU with Erdoğan as it pertains to the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople… But who can serve as Ecumenical Patriarch is also limited under Turkish law; the Patriarch of Constantinople has to be a citizen of Turkey. Furthermore, the Turkish government does not respect the Ecumenical Patriarch’s international personality and only recognizes him as a local bishop. And there are very few Orthodox Christians remaining within Turkey as a result of the severe persecution and seizures of religious properties during the past 100 years.”

Screenshot of the blessing bestowed upon President Putin of Russia by Russian Patriarch Kirill.

As a result of its policy of driving out Christians while insisting that only a Christian born in Turkey can serve as Patriarch, Turkey has undermined the unifying and centralizing role of the Patriarchate, leaving it open to political manipulation and abuse. In the interview, Gerasoulis explains the international geopolitical aims behind Erdoğan’s attempt to weaken the position of the Ecumenical Patriarch, the spiritual leader of 300 million Orthodox Christians worldwide, in favor of Patriarch Kirill, the head of the Russian Orthodox Church, a close ally of Vladimir Putin. Gerasoulis argues that Turkey’s proposed MoU would significantly undermine the Ecumenical Patriarch and further foment the ambitions of the Russian Orthodox Church and Putin’s adversarial government. Gerasoulis notes that, “For decades, the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople has been an able ally of the United States and the values that we represent; freedom, democracy, and human rights.”

[See Elias Gerasoulis: A geo-political perspective on the Turkish MoU, Cultural Property News, September 30, 2020.]

Poor Stewardship of Turkish World Heritage site, and Bombing of Others’ Monuments Make a Mockery of the Law’s ‘Self Help’ Requirements

As recent incidents both inside Turkish borders and in Syria by the Turkish military and their allies make clear, Erdoğan’s demands for archaeological protection are a specious cover for the political, religious, and economic goals of his ruling party. His actions are also in direct contradiction to the U.S. Cultural Property Implementation Act’s requirement that a government seeking import restrictions take self-help measures to preserve archaeological sites.

Armenian Catholic Church, Diyarbakir. Armenian Weekly.

In recent years, street fighting by Turkish troops destroyed two World Heritage Sites at Diyarbakir, the Armenian Catholic Church of Diyarbakir, a 1700-year-old Syriac Orthodox Church of the Virgin Mary and a Jewish synagogue. The Armenian Surp Giragos Catholic Church was ordered expropriated by the Turkish government.[xv]

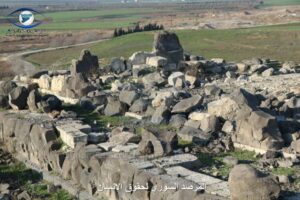

In January 2018, Turkish air forces flew into Syria and deliberately destroyed 60% of the Iron Age temple of ‘Ain Dara, the most outstanding, 3000-year-old Syro-Hittite monument ever excavated. ‘Ain Dara stands near to the northern Syrian town of Afrin. The temple was famous for its powerful, rough-cut guardian statues of lions and sphinxes, its intricate wall-carvings, and the giant, three foot long footprints carved into its stones at its entrance. Huge stone slabs were thrown for 300 meters by the bombing and giant statues smashed. Although the ancient site was open to the sky, providing no possible cover (and no claim was made by Turkey that insurgents were present), the bombing was characterized as part of a campaign against Kurdish separatists and apparently intended to extend Turkey’s buffer zone along the Syrian border.[xvi]

Temple at Ain Dara, after bombing by Turkish forces, Syrian Human Rights Observatory.

The Erdoğan administration has repeatedly sacrificed archaeological preservation inside Turkey in the cause of infrastructure development, for example, in the recent filling of the Hasankeyf Valley in Turkey’s Kurdistan region, to create the Ilisu Dam and hydroelectric project. The sites destroyed include the 12,000-year-old town of Hasankeyf, believed to be one of the world’s oldest cities. Hasankeyf contains remains of Neolithic cave-dwellers, a Byzantine bishopric, a Seljuk city, Arab fortress, and Ottoman military outpost. More than 300 historical sites will be submerged. The dam that will inundate these thousands of years of history is estimated to last for only 100 years.

Hasankeyf before the inundation by the dam, 23 May 2007, Photo by Herbert Frank from Wien, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.

The Association of Art Museum Directors stated in its testimony on the proposed Turkish MOU to the Cultural Property Advisory Committee at the Department of State on January 21, 2020 that:

“The AAMD does not support the request for an MOU because the Turkish government failed to satisfy any of the four determinants required for import restrictions under the CPIA. While all of the facts are important, perhaps the most troubling is Turkey’s failure to take measures to protect its cultural patrimony. Instead, it is taking affirmative steps to eradicate some of the country’s most important heritage—particularly that of its minority cultures and religions—through state sanctioned destruction of cultural patrimony. Nobody should condone this conduct. But that is exactly what the Committee will do if it concludes that Turkey qualifies for import restrictions and recommends the MOU.”[xvii]

Turkey Intends to Use MOU as a Tool to Claim Art from U.S. Collections, Not Halt Looting

Konya Archaeological Museum, sarcophagi and other antiquities from the ancient city of Çatalhöyük. By Murat Özsoy 1958, 27 November 2019, CCA-SA 4.0 license

There is little evidence of items looted from Turkey today making their way into U.S. museums or private collections. Instead, Turkey has sought to repatriate only very valuable objects that have been in U.S. collections for decades and even exhibited for many years in American museums, such as the Gueggnol Stargazer.[xviii] Turkish Culture and Tourism Minister Mehmet Nuri Ersoy admitted as much, saying that that the chief benefit of the Turkish MOU was that demands for repatriation of Turkish objects from the U.S. would be much simplified: “Legal struggles that last for years with enormous costs will be concluded in a very short time and with low costs. This is the biggest deterrent we have.”

In 2012-2013 the Metropolitan Museum in New York, the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, and the Pergamon Museum in Berlin all received demands from Turkey for the return of objects that have been in the museums’ collections for decades in what many called an “art war.” Technically, the new regulations can’t be

Pergamon Altar at Pergamon Museum, Berlin, Photo Raimond Spekking, 24 March 2004 © Raimond Spekking, license CC BY-SA 4.0

applied to objects already in U.S. museums and private collections. However, Turkey says it now wants proof that foreign museums have legal rights to numerous objects based upon Ottoman laws of 1884 and 1906. It says it has both legal and moral claims to artworks that have rested in foreign museums for more than a century. Of course, another reason for these domestically-promoted claims is the Turkish government’s plan to fill a new trophy museum with reclaimed treasures – the 270,000 square foot “Museum of the Civilizations” to be completed in Ankara in 2023.

This goal was reiterated in Turkey’s application for an MOU. According to the Public Summary of the Turkish request for an MOU made in 2019, “It is known that many cultural objects originating in Turkey exist in several museums and private collections in the USA and Europe. The sales at auction houses abroad as well as the online sales show that there is a flow of cultural property from Turkey to other countries.”

Cameo with portrait heads, 278–270/69 B.C. Greek, Sardonyx, from Pergamon

Antikensammlung, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

This argument is not supported by the facts. What auction and other sales actually showed is that many objects have left Turkey for centuries in trade throughout the Mediterranean world and beyond. Antiquities were not only exported because officials were lax and laws unenforced; many also came through legal agreements with the Ottomans, including through partage in archaeological excavations over more than 150 years. Sales of items in circulation for centuries are not actual evidence of current illegal traffic between Turkey and the U.S. They are evidence of past trade in objects, ranging from the common to the sublime.

While minor objects undoubtedly slip through its borders even today, Turkey has had a very effective Customs control for at least the last thirty years. The problems are mostly in the past; Turkey has long been known as a very bad place to be caught with smuggled antiquities. It not only has tough police and worse jails – Turkey has citizen activists committed to stopping smuggling. For decades, as well as inspection by Turkish Customs, shipments of antique items for export have been regularly reviewed by these volunteer experts, who are often associated with academic institutions and museums. But export review is internal and documentation that would help to establish the legitimacy of exported objects is not often provided. If Turkey provides no documents to legitimate exporters on the broad range of objects covered by the MOU, it is doubtful that under the MOU’s restrictive enforcement by U.S. Customs that the thousands of items shipped legitimately out of the country for decades can ever be proved to have been lawfully exported.

Cultural Heritage Enclave at the State Department Has Pursued a Policy at Odds with Human Rights and Religious Freedom

Boyun Egme. Gezi Park protesters, photo by Mstyslav Chernov, June 7, 2013, CCA-SA 3.0 Unported license.

The signing of the agreement with Turkey is the culmination of a State Department policy that puts dictatorships in charge of art and ideas. It rationalizes and justifies the absurd claim that a government whose secret police can sweep down and arrest tens of thousands of “subversive” students, teachers, journalists and intellectual enemies of the state somehow cannot stop looting by a few peasants, a few bad dealers or a few corrupt officials (since looting almost always happens with the collusion of local authorities).

The agreement of the US to block entry of religious property belonging to minority groups of Turkish origin now living abroad – many forced out by the Turkish government – and to return it to a country whose policies condone abuse of those same minorities raises serious questions about the administration of the Cultural Property Advisory Committee at the Department of State.

A whirling Sufi wearing gas mask at 2 June 2013 protests in Turkey in Gezi Park, Photo by Azirlazarus, CCA-SA 3.0 Unported license.

The State Department’s Bureau of Education and Cultural Heritage has encouraged claims by governments for all art from all periods of any country and has not hesitated to offer help on making such requests to the United States. The Bureau’s proactive pursuit of MOUs, despite its ostensibly administrative role, is aided and abetted by anti-collecting advocacy groups with ties to foreign governments that work closely with the State Department behind the scenes. It is noteworthy that the Antiquities Coalition strongly supported the signing of the Turkish MOU.

What makes the U.S. decision to ban entry to Turkish objects even worse, is that the State Department knows that the US-Turkish MOU will strengthen President Reccip Erdoğan’s ultra-nationalist agenda and his administration’s use of cultural nationalism to foster anti-democratic, anti-minority political goals.

The agreement requested by Turkey would recognize its government’s ownership of art made over the entire history of the region. Yet whose culture is actually being claimed? Modern Turkey’s history of antisemitism and religious discrimination and its 20th century genocides against Armenians and Greeks drove its non-Muslim and minority communities into the diaspora. Most of these peoples had lived in the region for thousands of years.

Academy Vigil Continues, academics protesting the detention of their colleagues, who were arrested because of signing the Academics for Peace leaflet. Photo by Hilmi Hacaloğlu, 9 April 2016, Voice of America, public domain.

Shouldn’t this history – and the current censorship of both history and ideas by the Turkish government – make the U.S. think twice? Shouldn’t the Turkish government’s denial of minorities’ role in its history and destruction of minority heritage be a factor in the decision whether to impose import restrictions under the CPIA? How can the U.S. say that Turkey is doing the best it can to preserve its heritage when the Turkish government is busy covering up and distorting history instead?

This is not the first time that the State Department’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs has handed a foreign dictatorship a diplomatic plum at the very moment that oppression of its own people by that dictatorship is worsening. The Bureau has recently ignored a scheduled review of a cultural property agreement with China despite that country’s active destruction of Uyghur culture and monuments – and its genocide against the Uyghur people.

The Bureau was eager to renew an MOU with Egypt this year, despite Egypt’s continuing, horrific human rights abuses of any individuals or group even mildly critical of its government. In the last two years, the Bureau has overseen the signing agreements giving dictatorial governments the right to control the heritage of religious minorities to Libya and five more MENA nations.

People protesting imprisonment of journalists from Cumhuriyet newspaper in Şişli, İstanbul.

1 November 2016, Photo by Hilmi Hacaloğlu, Voice of America, public domain.

It is remarkable that this has happened at the same time that other State Department sections that set policy on human rights and religious freedom have vigorously condemned Turkey, China, Egypt, and others for horrific abuses against minorities. There is an explicit contradiction between the severe criticism leveled at the Turkish government by the State Department’s human and religious rights sections and the blessing bestowed on Turkey’s policies of repression by its Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs. Such contradictory policy should raise questions about the administration of the Cultural Property Advisory Committee, both by Congress and in the highest levels of an administration that claims to be committed to transparency and ethical governance.

[i] Armenian National Committee of America (ANCA), “Last Minute U.S.-Turkey Accord Grants Ankara Rights to Christian Cultural Heritage,” https://anca.org/press-release/last-minute-u-s-turkey-accord-grants-ankara-rights-to-christian-cultural-heritage/

[ii] Import Restrictions Imposed on Categories of Archaeological and Ethnological Material of Turkey, Federal Register, Vol. 86, No. 114, Wednesday June 16, 2021, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2021-06-16/pdf/2021-12646.pdf

[iii] Memorandum of Understanding Between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of the Republic of Turkey Concerning the Imposition of Import Restrictions on Categories of Archaeological and Ethnological Material of Turkey, January 19, 2021, https://eca.state.gov/files/bureau/signed_mou_english.pdf.

[iv] Currently the U.S. has import restrictions on objects from Algeria, Belize, Bolivia, Bulgaria, Cambodia, China, Chile, Colombia, Cyprus, Ecuador, Egypt, El Salvador, Greece, Guatemala, Honduras, Iraq, Italy, Jordan, Libya, Mali, Peru, Syria, and Yemen. See https://eca.state.gov/cultural-heritage-center/cultural-property-advisory-committee/current-import-restrictions.

[v] Supra, note 2.

[vi] Currently, Designated Lists form complete embargoes against objects from source countries. This is contrary to the terms of the Cultural Property Implementation Act and beyond the authority given under the law. Under the CPIA, archaeological material must be (1) of cultural significance; (2) at least 250 years old; and (3) normally discovered as a result of scientific excavation, clandestine or accidental digging, or exploration on land or under water. Ethnological material must be (1) the product of a tribal or nonindustrial society; and (2) important to the cultural heritage of a people because of its distinctive characteristics, comparative rarity, or its contribution to the knowledge of the origins, development, or history of that people. Cultural Property Implementation Act (CPIA), 19 U.S.C. §2601; for additional discussion of the criteria for cultural property agreements and the U.S. State Department’s administration of the CPIA, see Kate Fitz Gibbon, “CPAC – Building a Wall Against Art,” Cultural Property News, June 28, 2018, https://culturalpropertynews.org/cpac-building-a-wall-against-art/.

[vii] S. Rep. 97-564 at 2, 12 (2d Sess. 1982).

[viii] James F. Fitzpatrick, “Falling Short – the Failures in the Administration of the 1983 Cultural Property Law,” 2 ABA Sec. Int’l L. 24, 24 (Panel: International Trade in Ancient Art and Archeological Objects Spring Meeting, New York City, Apr. 15, 2010).

[ix] Supra, note 7 at 4, 12.

[x] See “Coalition Opposes Cultural Property Requests by Repressive Governments,” Cultural Property News, August 27, 2020, https://culturalpropertynews.org/coalition-opposes-cultural-property-requests-by-repressive-governments/

[xi] On July 11, 2020, Turkey’s Council of State issued an order that administration of Hagia Sophia (Aya Sofia), a major World Monument and one of Turkey’s most popular museums since 1934, should be transferred from the administration of Turkey’s Ministry of Culture to the Presidency of Religious Affairs. See Gary Vikan, “Hagia Sophia No Longer a Museum: US Should Deny Turkey’s Request for Blockade on Art,” Cultural Property News, See also “Interview with Robert G. Ousterhout: The Preservation and Reconversion of Kariye Camii,” https://culturalpropertynews.org/interview-robert-g-ousterhout-the-preservation-and-reconversion-of-kariye-camii/

[xii] For a broad discussion of the changing meaning of laiklik, see Mustafa Akyol, “Turkey’s Troubled Experiment with Secularism,” Century Foundation, April 25, 2019, https://tcf.org/content/report/turkeys-troubled-experiment-secularism/?agreed=1

[xiii] Aykan Erdemir and Tugba Tanyeri-Erdemir, “Turkish Government’s Hagia Sophia Rhetoric Adds Insult to Injury,” Providence, July 24, 2020, https://providencemag.com/2020/07/turkish-government-hagia-sophia-rhetoric-adds-insult-injury/.

[xiv] Aykan Erdemir and Nadine Maenza, “Turkey Needs to Change its Policy and Rhetoric Toward Religious Minorities,” Newsweek, April 29, 2021, https://www.newsweek.com/turkey-needs-change-its-policy-rhetoric-toward-religious-minorities-opinion-1586803

[xv] See Leela Jacinto, “Destruction of Kurdish Sites Continues as Turkey Hosts UNESCO,” FRANCE 24, July 14, 2016, https://www.france24.com/en/20160714-turkey-unesco-heritage-sites-damage-kurdish-diyarbakir-sur

[xvi] “Turkey Bombs 3,000 Year Old Syro-Hittite Site to Rubble,” Cultural Property News, February 3, 2018, https://culturalpropertynews.org/turkey-bombs-3000-year-old-syro-hittite-site-to-rubble.

[xvii] AAMD, “Statement of the Association of Art Museum Directors Concerning the Request by the Government of Turkey to the Government of the United States of America Concerning the Imposition of Import Restrictions to Protect its Cultural Patrimony Under Article 9 of the 1970 UNESCO Convention,” January 21, 2020, Meeting of the Cultural Property Advisory Committee.

[xviii] Maximiliano Duron, “Turkey Seeks to Recover $14.4 M. Stargazer Sculpture in U.S. Federal Court,” ARTnews, April 12, 2021, https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/turkey-stargazer-sculpture-christies-lawsuit-1234589493.

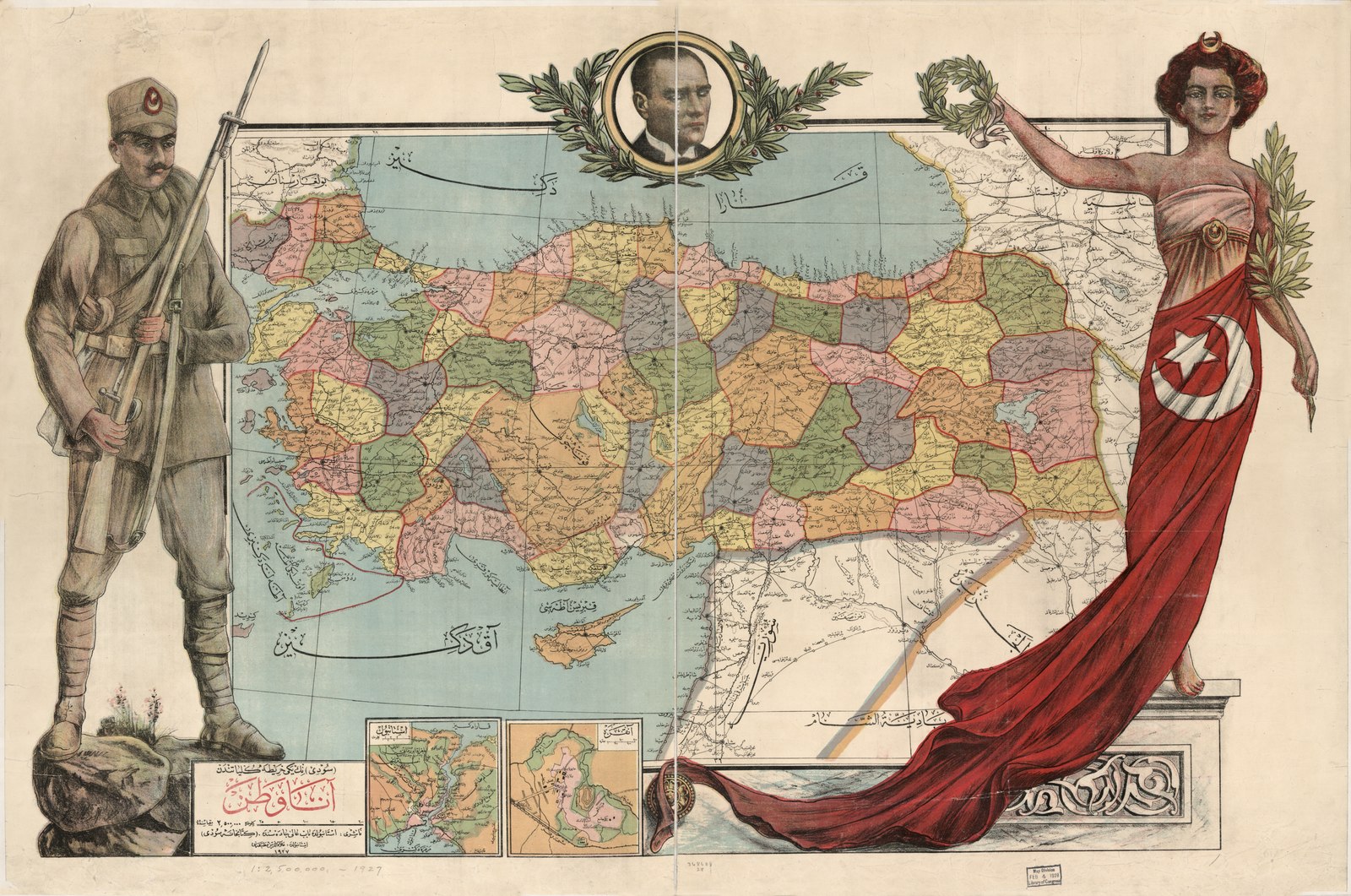

Map of Turkey’s political and administrative boundaries in 1927 with insets showing the Istanbul Region and Ankara, a portrait of Atatürk, and a soldier and a woman draped in the Turkish flag. Kitabkhane-Yi Sûd, Collection of US Library of Congress's Geography & Map Division.

Map of Turkey’s political and administrative boundaries in 1927 with insets showing the Istanbul Region and Ankara, a portrait of Atatürk, and a soldier and a woman draped in the Turkish flag. Kitabkhane-Yi Sûd, Collection of US Library of Congress's Geography & Map Division.