“Understanding the important role of the green highlands in providing habitat for subsistence plants and animals, as well as capturing and filtering water from passing storms, the Navajo refer to such places as “Nahodishgish,” or places to be left alone.”

President Barack Obama, December 28, 2016

Bears Ears National Monument Given Endangered Status

Bears Ears National Monument in Utah was named as an endangered site on the World Monuments Fund (WMF) list for 2020. Bears Ears was selected from among 250 nominations. The site was one of 25 around the world chosen to highlight situations where conservation efforts are urgently needed to protect cultural heritage and to preserve the sites’ social impact. The WMF cited the monument’s relationship to regional tribes and pueblos, its vast number of archeological and sacred sites, and the impending threat to these from a new management plan proposed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) in late summer 2019 that would open vulnerable lands to oil and gas, agricultural, and off road recreational development.

Juniperus osteosperma (Utah juniper) at Bears Ears. Photo by Brewbooks from near Seattle, USA. 23 September 2010. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license. Wikimedia Commons.

The future impact of federal management plans can be seen in decisions made for other monuments. Federal agencies pressing for large scale mechanical vegetation removal projects such as the BLM’s plan to remove some 30,000 acres of pinyon pine forest from one section of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in Utah lost a bout in the courts in September 2019. The plan would have used a shredder to destroy trees in place and drag large chains between two bulldozers to rip trees from the ground, a process called “mastication.” Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance (SUWA), Western Watersheds Project, The Wilderness Society, and the Grand Canyon Trust succeeded in halting the plan in Grand Escalante. According to Kya Marienfeld, wildlands attorney for the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance, plans for using these scientifically unjustified processes continue in other parts of Grand Staircase. Conservationists note that these destructive vegetation removal processes are included in the Bears Ears management plan.

Litigation regarding the status of Bears Ears National Monument has focused on the community and ecological losses resulting from radically shrinking and splitting apart the protected lands – and then opening them to development. It has been ongoing since President Donald Trump announced a 85% reduction of the size of the newly created 1.35 million acre Bears Ears National Monument on December 4, 2017.

Lawsuits Filed Against Use of Antiquities Act and Damaging Management Plans

Environmental groups, Native American tribes, paleontologists, archeologists, and Patagonia, a retailer of outdoor recreational goods, immediately filed three lawsuits, which were later consolidated into a single case currently being considered in Federal court. The plaintiffs contended that the President lacked authority under the Antiquities Act of 1906 to reduce the size of monuments, a role the law has allocated to congress.

Ruins at Chaco Culture National Historical Park. Photo by National Park Service. Chaco Canyon was a major center of Puebloan culture between AD 850 and 1250. The Chacoan sites are part of the homeland of Pueblo Indian peoples of New Mexico, the Hopi Indians of Arizona, and the Navajo Indians of the Southwest. Wikimedia Commons.

The defendants, Donald Trump, Brian Steed (former Deputy Director of Programs and Policy, Bureau of Land Management and current Executive Director of Utah Department of Natural Resources), Ryan Zinke (former US Secretary of the Interior), Sonny Perdue (US Secretary of Agriculture), and Tony Tooke (former Chief of the U.S. Forest Service) moved to dismiss the combined lawsuits on the grounds that the “Plaintiffs lack standing to bring their claims, that Plaintiffs’ claims are not ripe for adjudication, and that the Antiquities Act, and the Act alone, provided President Trump with the authority to decrease the size of the monument.” The motion to dismiss was denied on September 30, 2019.

In her order, Federal District Judge Tanya S. Chutkan also noted that the plaintiffs could file an amended complaint to address “the impending release of a series of new management plans regarding Bears Ears National monument.”

Numerous reports indicate that the move to shrink the monument was an energy extraction decision. Native American and environmental groups have argued that all management plans and oil and gas lease sales should be deferred within the monument’s original boundaries since President Trump’s 2017 order to reduce Bears Ears National Monument is being challenged in federal court. Nonetheless, the BLM has proposed a management plan and Environmental Impact Statement for Shash Jaa and Indian Creek portions of Bears Ears National Monument

In February 2019 the Utah School and Institutional Trust Lands Administration (SITLA) withdrew parcels from auction and refunded the winning bids on the parcels that had already sold within the original monument boundary.

New Navajo Majority San Juan County Commission Sustains Monuments Protected Status

Also in February 2019, a newly reconstituted San Juan County Commission, seated in the county where Bears Ears National Monument is located, and which had previously opposed creation of the monument, passed two resolutions aimed at protecting the Monument.

The San Juan County Commission’s about-face came after a November 2018 special election when the county’s first majority Navajo commission was sworn into office. This precedent followed redistricting ordered by U.S. District Court Judge Robert Shelby after finding San Juan County districts racially gerrymandered, in violation of the Voting Rights Act. That decision was upheld after an appeal by San Juan County at the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals.

The first resolution rescinded all prior Commission resolutions in opposition to the monument and replaced them with a resolution to oppose the reductions in the monument’s size. The second resolution withdrew the Commission from the Bears Ears lawsuit as interveners on the side of the federal defendants.

Since the redistricting, the commission has faced a number of challenges to its new authority. The most recent was a November ballot initiative, San Juan County Proposition 10, which would have “created a study committee to consider and possibly recommend a change to the county’s form of government.” According to Zak Podmore, a Report for America corps member who writes about San Juan County for the Salt Lake Tribune, “Many saw [the proposition] as an attempt to undermine the county’s first majority-Navajo commission.” The initiative was defeated.

Chaco Cultural Heritage Area Protection Act Update

Kivas, Chaco Canyon, New Mexico. Photo by National Park Service, U.S. government agency. Wikimedia Commons.

On April 9, 2019 New Mexico Congressman Ben Ray Lujan introduced H.R. 2181, the Chaco Cultural Heritage Area Protection Act. The bill passed the House and was introduced as S. 1079 in the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources in the Senate on October 31, 2019. The act withdraws 316,076 acres of federal land rich in oil, natural gas, coal and other minerals surrounding Chaco Cultural Historical Park from development.

Increased oil and gas drilling close to the park had sparked concern among New Mexico and Arizona tribes and pueblos, as well as the general public, that encroachment would impact archeological and ceremonial sites in the region. Environmental and archeological groups have voiced concern that energy extraction development so close to the park would impact its status as a World Heritage site and International Dark Sky Park.

Back and Forth Decisions and Delays in Court Hearings Will Allow More Damage

In May 2019, the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled on the question of “whether the Bureau of Land Management violated the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) and the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) in granting more than 300 applications for permits to drill horizontal, multi-stage hydraulically fracked wells in the Mancos Shale area of the San Juan Basin in northwestern New Mexico.” (Dine Citizens Against Ruining our Environment v. Bernhardt, No. 18-2089)

The Court upheld the lower court’s dismissal of the claim that the BLM failed to comply with the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA). At the same time it reversed the lower court’s decision in regard to National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) claims as to five specific Environmental Assessments (“EAs”)

Wolfman Panel located on Comb Ridge in southeastern Utah. Author Phil Konstantin,

8 February 2017, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

In this part of the decision, the Court upheld the environmental and tribal plaintiffs’ claims, stating that “…the BLM never considered the cumulative impact of the water use associated with the 3,960 reasonably foreseeable horizontal Mancos Shale wells for five specific EAs.”

The BLM quickly responded with Findings of No Significant Impact (FONSIs) and Environmental Assessments (EAs) that denied that serious environmental problems would result from the drilling.

Eighteen environmental and tribal groups quickly rallied with a letter to Tim Spisak, State Director of the New Mexico State Office of the BLM, asking him to reject the reports and requesting public hearings in response to the 10th Circuit’s findings.

WildEarth Guardians, an environmental advocacy organization focused on wildlife and wilderness issues, had submitted technical comments to the BLM’s State Director and to the Farmington field office describing discrepancies in process and lack of data in the FONSIs and EAs.

In August 2019 a coalition of citizens’ and environmental groups, including Diné Citizens Against Ruining our Environment, and WildEarth Guardians, filed a new lawsuit [Dine Citizens Against Ruining our Environment v. Bernhardt (1:19-cv-00703)] in the US District Court for New Mexico “to leverage the [higher] court’s precedent and target Bureau of Land Management’s approval of wells between September 2016 and the present.”

The lawsuit is accompanied by a motion for a temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction. The motion calls on the court to order a halt to further development of the wells at issue in the case.

Within days, oil companies BP America Production Co. and DJR Energy Holdings sought to intervene as defendants, stating that a temporary restraining order would affect their investments. Since then, other groups have motioned for leave to intervene as defendants, including the American Petroleum Institute and a group of citizens from the Navajo Nation, “the Navajo Allottees”, whose mineral rights could be affected by the injunction.

By the end of August the court issued an Order Regarding Setting of Hearing on Motion For Injunctive Relief to clarify the “speed with which matters in this complex environmental case can be heard.” Judge William Paul Johnson said there would be significant delay given the Court’s exceedingly high caseload of criminal cases along the border, and the need to review over 3,200 exhibits from all parties in the case. He denied the environmental and Native American plaintiffs’ request for a temporary restraining order. The delay could result in considerable more damage to the lands concerned, since in the interim, hydraulic fracturing “fracking” will continue in the area around Chaco Culture Historical Park.

Congresswomen from U.S. and Brazil Stress Importance of Protecting Wildlands and Indigenous Lands

U.S. Congresswoman Deb Haaland and Brazilian Congresswoman Joênia Wapichana cited to a recent Yale study in a joint opinion piece, Protecting indigenous lands protects the environment. Trump and Bolsonaro threaten both, in the Washington Post. They summarized the study’s findings: “indigenous peoples in control of their lands are the most effective stewards of climate-regulating tropical forests.”

The southwestern United States is uniquely positioned in this debate. It contains some of the largest deposits of minerals and fossil fuels on the planet as well as some of the “densest and most significant cultural landscapes in the United States.”[1] The Southwest is also home to multiple tribes and pueblos that have retained and are reviving their lifeways and traditions with direct ties to these cultural landscapes, the sites that they contain, and “the traditional ecological knowledge “ that “offers critical insight into the historic and scientific significance of the area.”[2]

The opinion piece echoed broad concerns among environmental and climate scientists. A letter signed by over 11,000 scientists from around the world set forth powerful evidence that climate change is accelerating much faster than anticipated and that right human action could slow down and even reverse this trend if applied quickly enough. NASA notes that the extraction and use of fossil fuels is at the center of the climate change debate, and account for the majority of the “greenhouse gases” linked to an overall warming of the planet.

Most agree that slowing the extraction of oil and gas would have a significant impact on the future climate of the planet. Maintaining and protecting biodiversity and ecosystems, planting trees, reducing dependence on fossil fuels would help the planet to recover and stabilize. A growing body of research also demonstrates that indigenous culture and lifeways help protect biodiversity, and can provide guidance for how people can live in harmony with diverse ecosystems and a changing climate.

Cultural Background on Bears Ears and Greater Chaco Region

What is now Chaco Culture Historical Park in the northwest corner of New Mexico was once at the center of a vast civilization extending hundreds of miles in all directions. It included the area around Bears Ears National Monument. The Hopi, Zuni, Navajo and Pueblo peoples of the Four Corners region (Utah, New Mexico, Colorado, and Arizona) all have spiritual ties to this region. Chaco Canyon and Bears Ears are held in cultural memory through oral tradition, stories passed down from generation to generation linking Native American communities to the land.

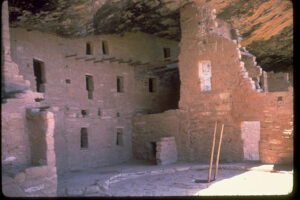

Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado, Mesa Verde offers a spectacular look into the lives of the Ancestral Pueblo people who made it their home for over 700 years, from A.D. 600 to A.D. 1300. Today, the park protects over 4,000 known archeological sites, including 600 cliff dwellings. These sites are some of the most notable and best preserved in the United States. Photo by National Park Service. Wikimedia Commons.

The Ancestral Puebloan culture flourished for over 300 years in what is now the US Southwest. There was an extensive trade network with Mesoamerican cultures evidenced by archaeological finds of cacao, in Chaco Canyon, and macaws in the Chaco Canyon and Bears Ears regions. Marine shells from the Pacific coast and raw and crafted copper came from what is now western Mexico. Even today, the importance of these items can be seen in their use as elements of traditional costumes at pueblo dances and in the names of the clans within pueblos.

It has been estimated that in the original Bears Ears National Monument alone there are over 100,000 archeological sites; most are unexcavated or documented in detail. Chaco Canyon holds the remains of grand kivas and great houses – Pueblo Bonito, Una Vida, Peñasco Blanco and others. Linked to this canyon are thousands of other sites, roads and outliers for hundreds of miles in all directions.

Cultural Property News will continue to report on the impact by energy development interests on the cultural landscape of Bears Ears National Monument and Chaco Culture National Historical Park. Previous coverage includes:

Chaco Canyon Update: BLM Delays Leases Affecting Industry, Indians, Archaeologists, March 7, 2018.

Greater Chaco Leases OK’d: Natives, Environmentalists Stunned, Cultural Property News, April 26, 2018.

Chaco Canyon Update: One Year Later, February 4, 2019.

Chaco Canyon, Grand Staircase-Escalante, and Bears Ears Roundup: Washington DC’s Energy Policy, Cultural Heritage, and the American Southwest, July 27, 2019.

[1] Presidential Proclamation — Establishment of the Bears Ears National Monument, President Barak Obama, December 28, 2016, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2016/12/28/proclamation-establishment-bears-ears-national-monument

[2] Id.

Cedar-mesa Ruins Bears Ears National Monument. Photo by US Bureau of Land Management, 10 August 2016. Public domain.

Cedar-mesa Ruins Bears Ears National Monument. Photo by US Bureau of Land Management, 10 August 2016. Public domain.