On January 31, 2018, a new Emergency Red List for Yemen was announced at a ceremony at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The Red List was funded, produced, and published in partnership between the US Department of State’s Bureau of Cultural Affairs and the International Council of Museums (ICOM). The Yemen Red List has raised extreme concerns among the broader Jewish community, and especially among exiled Jews from the Middle East. Yemen is just the latest nation to assert its government’s ownership and control over the heritage of Jewish peoples that were persecuted and driven to leave en masse in the mid-20th century, after the partition of Palestine and creation of a Jewish state in 1947.

Iraq, Syria, Egypt, and Libya have already laid claim to all of their former Jewish population’s heritage. Yet the Department of State has long held to the position that people do not have legitimate claims to their history or their art; only governments have claims to art and history.

The Department of State describes Red Lists as “illustrated booklets designed for customs officials, police officers, museums, art dealers, and collectors, to help them recognize the general types of archaeological, ethnographic, and ecclesiastical objects that have been looted from cultural sites, stolen from museums and churches, and illicitly trafficked.”

While Red Lists may accomplish the goal of helping law enforcement to recognize a country’s most distinctive artworks, they do not help to determine if an artwork has been stolen or illicitly trafficked – or not. They are instead a simplified laundry-list of characteristic items originating in a specific geographic area – in this instance, within the borders of the present day nation of Yemen.

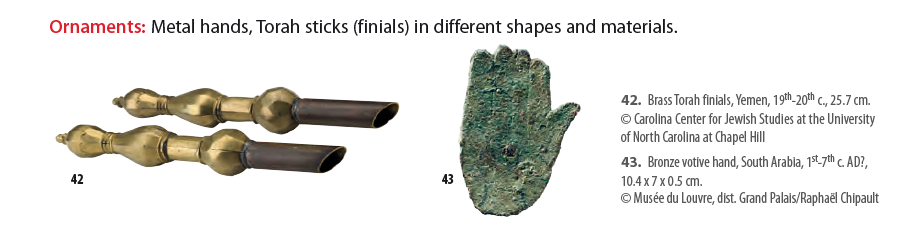

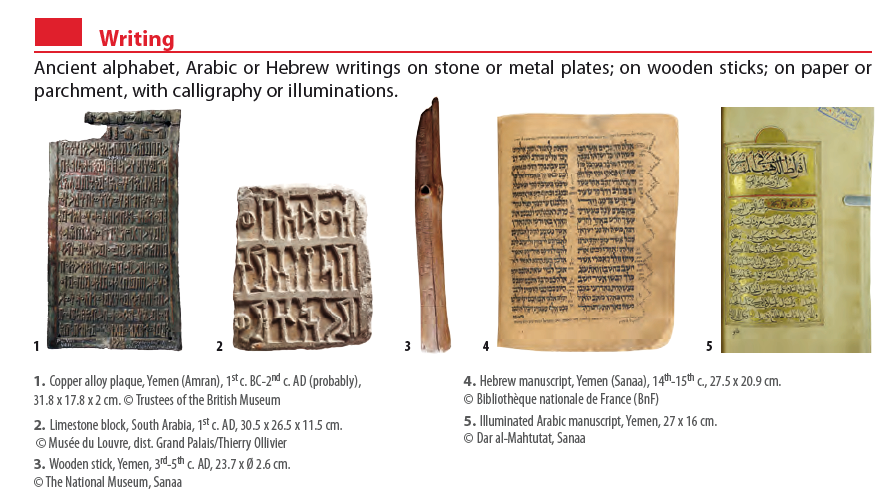

Illustrations from Yemen Emergency Red List. Credit ICOM and US Department of State.

The photographs that accompany Red Lists are not pictures of actual looted objects; on the contrary, the text acknowledges that they depict objects in museum collections. Despite the overlap in appearance between items in legitimate trade and items that may have been stolen or illicitly exported, ICOM’s France Desmarais stated that, “We are now strongly advising collectors to avoid the objects on the list altogether, or at least to be extra cautious and thoroughly check the legality of provenance.”

While caution in acquiring antiquities is the duty of any responsible museum or collector, especially when they may come from a nation in the midst of a civil war, do ICOM and the Department of State view all cultural heritage outside a source country as illicit?

It seems so. The texts that accompany each Red List make no mention of any lawful trade in antiquities. More importantly, there is no acknowledgement of legitimate private or community ownership, even in the case of heritage belonging to exiled peoples. And surprisingly, since ICOM is a ‘museum’ organization, the list says nothing about the role of museums in preserving heritage.

Instead, the Red List emphasizes that all the items listed are legally the property of the government of Yemen. When asked whether collectors would be able to obtain licenses for export, Desmarais told The Art Newspaper that “It’s difficult, but not impossible. It is important to respect the sovereignty of nations, so if it is required by law, we must abide.”

The announcement of the Emergency Red List did not indicate how Yemeni art and artifacts were shown to be at risk of illicit trafficking. In fact, Met curator of Islamic art Sheila Canby stated that few objects of Yemeni origin had come on the market since the war began in 2015. She told the Art Newspaper that, “I haven’t really seen anything from Yemen in any of the big auctions since the most recent war began. Nor has any art dealer come to us with anything from Yemen,” but went on to warn the art market and collectors of the need to be vigilant.

Other documentation of illegal trafficking from Yemen also shows it to be at a minor level. The World Customs Organization released a 249 page Illicit Trade Report in early February 2018, devoting many of its pages to examining the trade in cultural property – although compared to other forms of illegal trafficking, the cultural property segment was miniscule. A report specifically on Yemen’s illicit cultural property trade stated that Yemen Customs reported five seizures in 2016, resulting in the retention of over 110 individual cultural objects, including coins, statues and calligraphy. The goods were destined for East Africa and Jordan. All the items were in personal luggage stopped at the airport or on their way there, and clearly smaller items.

Deliberate Damage and Destruction Has been the Hallmark of the Yemeni Conflict

Dhamar Museum Before 2015. https://imgur.com/a/iQwBJ

Yemen has suffered terrible damage to all of its architectural and monumental heritage during the ongoing conflict. In March 2015, the Shia al-Badr and al-Hashoosh mosques in Sana’a were attacked during midday prayers, killing 142 people and wounding more than 350; ISIL claimed responsibility. Museums have also been seriously damaged; the Zinjibar Museum in Abyan Province was looted and is now used as shelter for refugees. In July 2015, the 16th century mosque of Sheikh Abdulhadi al-Sudi in Taez, in southwestern Yemen, was bombed by Salafist gunmen. The mosque was the most famous of Taez’ antique buildings, known for its association with Yemen’s Sufi tradition. Sufism’s mystical teachings are rejected by the ultra-conservative Sunni Salafist movement.

The 2500-year-old Old City of Sana’a has been a UNESCO World Heritage site since 1986. It holds one hundred mosques and thousands of pisé rammed-earth, tower-like houses, many of which are decorated with geometric patterns of fired-brick and white gypsum. This architectural style dates to the 11th century, when Sana’a became a center for the spread of Islam from the 7th century onward. The Great Mosque of the city was built only 6 years after the Hijra and was the first mosque outside of Mecca and Medina. Although the government of Yemen mandated the preservation of Sana’a through its Antiquities Law of 1997 and Building Law of 2002, it has long been criticized for failing to preserve the building standards required under the UNESCO designation.

Now, the situation is far worse. Not only have terrorist groups and other non-state actors deliberately demolished many monuments and homes, but outside government forces, notably Saudi Arabia, have targeted civilian and historic sites in Sana’a and other areas of Yemen.

Dhamar Museum After Saudi Airstrikes in 2015. https://imgur.com/a/iQwBJ

The Dhamar Museum, a major regional museum that housed over 12,000 artifacts, was blown to bits by Saudi forces in May 2015. A major documentation project by the Uniersity of Pisa and Yemen means the records of 700 ancient inscriptions are available to scholars online. The director of the documentation project, Alessandra Avanzini told National Geographic that, “Frankly, when we started the project, I did not imagine that ‘to save’ was to be taken literally.”

The Great Dam of Marib, built by the Sabaeans in 800 BCE, was one of the most important archeological sites in the Arabian Peninsula. In May 2015, it was destroyed by Saudi bombing. In a 2017 article in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Abdulhakim al-Sayaghi, an architect and senior consultant with the Cultural Heritage Unit of the Social Fund for Development, stated that, “More than 95 percent of [the destroyed] sites have been destroyed by the Saudi-led coalition.”

Given that the destruction of war has been so great, and the illicit removal of cultural items so relatively sparse, as shown in the World Trade Organization report, why is the Department of State so focused on illicit trade, when a US ally is actively engaged in obliterating key monuments of Yemen’s cultural heritage?

Red List Identifies Yemen’s Rich Jewish Heritage as Yemeni Government Property

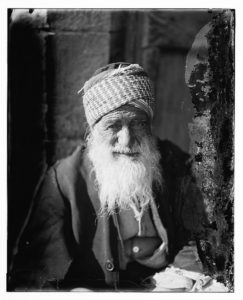

Arab Jew from Yemen, http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/matpc.06795, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

The government of Yemen seems very concerned with reclaiming the heritage of its exiled peoples. Jewish (and also Christian) art, artifacts and heirlooms are included in the items covered by the Red List. Jewish religious artifacts and manuscripts are pictured and explicitly included. The Yemen Red List includes photographs of a pair of Torah finials and a Hebrew manuscript.

The Red List emphasizes that all cultural items listed are legally the property of the Yemeni government. It references two provisions of Yemen’s Law on Antiquities, one of which prohibits the sale of archaeological objects or giving of national cultural heritage objects, whether registered or not, or to transfer cultural property. It is also forbidden to export archaeological or cultural objects or natural samples except for restoration work or temporary loan.

During the 2000 years that Jewish communities lived in Yemen, they experienced violent persecution under some South Arabian rulers, and at other periods were a tolerated and respected element of the region’s cultural and economic life. Jews were famed craftsmen, creating some of the earliest sophisticated textiles of the Islamic world, including 10th century silk ikats; they worked in metal of all kinds, and produced inlaid and decorated furniture.

Jewish craftsmen are also famed for carving the traditional Yemeni daggers, but because of sumptuary laws in Yemen were forbidden from wearing them, or from wearing new clothes.

Jews were most famous for making the silver jewelry for which Yemen is renowned. Writing in “The Yemenites: Two Thousand Years of Jewish Culture,” author Ester Muchawsky-Schnapper writes that:

“Making jewelry was an almost exclusively Jewish profession everywhere in Yemen, and even in areas like the Hadramat, where the silversmiths were Muslims, it now appears that many of them were descendants of Jewish converts. In the silver market of Sana’a, for instance, there were up to 300 Jewish silversmiths at a certain time, and in the town of Dhamar one third of all the Jewish craftsmen were silversmiths.”

The Yemenites: Two Thousand Years of Jewish Culture, p 113.

The Government of Yemen Claims Superior Rights to Jewish Heritage

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu holds an 800 hundred years old torah scroll as he poses for a picture with Yemenite Jews who were brought to Israel earlier this morning as part of a secret rescue operation, at the Knesset, the Israeli parliament in Jerusalem, March 21, 2016. Photo by Haim Zach/Government Press Office Israel.

Between 1949 and 1950, following the 1947 UN Partition Plan, 47,000 individuals, the majority of the Yemeni Jewish population, were brought from Yemen to Israel in an emergency airlift dubbed Operation Magic Carpet. Only small pockets of Jewish communities remained.

Nineteen Jews remaining in Yemen in 2016 were brought to Israel in what is described as a “covert airlift.” There are fewer than 40 or 50 remaining in Yemen today. In April 2017, Yemen’s information minister Moammer al-Iryani told Israel Radio that the community in Sana’a which is held by the Houthis are a severe risk because the Houthi see Jews as enemies who must be removed from Yemen in an ethnic cleansing.

The refugees who came in 2016 brought with them their community’s 800-year-old leather Torah, and proudly displayed it at a meeting with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Sulaiman Dahari, a rabbi, had carried it to Israel in a duffel bag.

Soon after, there were reports that an Orthodox Jewish man and an airport employee had been arrested. The airport employee, a Muslim, was accused of purposefully allowing Dahari to pass through security with the Torah.

Moti Kahana, of the New York based NGO Amalia, which holds Jewish community artifacts from Syria, was quoted saying, “When I saw the scroll in the media I knew the Yemenite government would complain – they would say that international law was broken.

Avi Mayer of the Jewish Agency told the Jewish Chronicle in March 2016 that, “The notion that the Torah should have been left, without protection, in a country torn apart by a violent civil war involving several parties that are viciously hostile to Jews, is preposterous. The Torah is part of the proud heritage of Yemenite Jewry and that heritage will live on in the state of Israel.”

In the Red List, however, there is no recognition whatsoever that any Jewish community in the diaspora has rights to cultural property; all Jewish cultural heritage is under the authority and control of the government of Yemen, and any items seized by other nations as a result of publication on the Red List should be returned to the government of Yemen.

Red Lists Closely Parallel US Import Restrictions

While the stated intention of the Emergency Red Lists is to make it easy for law enforcement and others to recognize objects at risk of looting from each country, historically, Red Lists have also served other aims.

In addition to the Yemen list, the State Department has supported the publication of lists for Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, West Africa, Libya, Egypt, Cambodia, China, Central America and Mexico, Haiti, Colombia, and Peru..

The State Department’s Bureau of Cultural Affairs, which funds and partners ICOM in creation of the Red Lists, also administers the Cultural Property Advisory Committee to the President, or CPAC. CPAC operates under the 1983 Cultural Property Implementation Act to respond to emergency situations and to requests from UNESCO-member art-source countries for import restrictions when looting threatens their cultural heritage.

If CPAC determines that the requesting nation has met certain criteria, then CPAC may recommend that the President impose selective import controls on that nation’s cultural property.

These criteria, much simplified, are that specific cultural property in a nation is at risk, that the nation has taken steps to protect its own cultural property, that it has endeavored to make its heritage accessible through cultural exchange with the US, that other nations with major markets have imposed similar restrictions, and that no less drastic step will help. (For more on CPAC and the Memorandum of Understanding process, see Cultural Property News, Get the Facts)

Every single Red List supported by the Department of State is paralleled by a Memorandum of Understanding under the Cultural Property Implementation Act or a separate piece of legislation supported by the State Department that imposes identical restrictions to a MOU. The only exception is Mexico, which is covered by even more longstanding US legislation barring importation of antiquities. The Department of State reviews these Memoranda of Understanding every five years, and the issuance of Red Lists further incentivizes the apparently perpetual renewal of restrictions on import into the US.

In order for the ICOM Emergency Red Lists to be respected as expressing the views of a disinterested international organization, there is a need for greater transparency regarding how ICOM and the State Department create the Red Lists, and what process is followed to ensure that the Red Lists truly serve the purpose of assisting customs authorities worldwide, not merely smoothing the way to more and more restrictions on the circulation of cultural property across the globe.

Until that happens, there is a strong likelihood that the main result of its publication will be a request from Yemen for US import restrictions.

Illustrations from Yemen Emergency Red List. Credit ICOM and US Department of State.

Illustrations from Yemen Emergency Red List. Credit ICOM and US Department of State.