“The Hopi footprints and clouds are part of a living, sacred landscape that nourishes and sustains Hopi identity. This landscape is steeped in cultural values and maintained through oral traditions, songs, ceremonial dances, pilgrimages, and stewardship.”

Letter from The Hopi Tribe to President Barak Obama and Utah Senators and Congressmen, dated September 30, 2014.

Most reporting on the current administration’s reductions in the size of major Southwestern monuments center on the collision between energy and mineral developers on one side and archaeologists, environmentalists, and native groups on the other.

Monument designations are about much more than land use, however. Although the monument designations were all made under the 1906 Antiquities Act, tribal council decisions (and in part, the eventual monument designations) were threads within a broader public policy discussion involving the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA), Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), The Archaeological Resources Protection Act of 1979 (ARPA), the American Religious Freedom Act and Executive Order 13007 (1996)(which acts in furtherance of federal treaties and includes accommodations for sacred sites).

Beyond the development of public policies for monument designation, there is a fundamental concept – something called the “Native American Traditional Cultural Landscape” on which Indian objections are also grounded. The concept of a “cultural landscape” has become part of the legal arguments for and against reducing the size of the lands that form the Monuments. Native concerns for preserving the cultural landscape are an integral part of the arguments for a more expansive definition of these monuments.

Southwestern Tribes and the Native American Cultural Landscape

The Hopi have long argued in support of a National Conservation area or National Monument that would include greater Cedar Mesa including Alkali Ridge and Montezuma Canyon in Southeastern Utah. A letter dated September 30, 2014 from the Hopi tribe describes its relationship to ancestral lands and the archaeological sites within it:

“Hopi migration is intimately associated with a sacred Covenant between the Hopi People and Maasaw, the Earth Guardian, in which the Hopi People made a solemn promise to protect the land by serving as stewards of the Earth. In accordance with this Covenant, ancestral Hopi clans traveled through and settled on the lands in and around southeastern Utah during their long migration to Tuuwanasavi, the Earth Center on the Hopi Mesas.”

“The land is a testament of Hopi stewardship through thousands of years, manifested by the “footprints” of ancient villages, sacred springs, migration routes, pilgrimage trails, artifacts, petroglyphs, and the physical remains of buried Hisatsinom, the “People of Long Ago,” all of which were intentionally left to mark the land as proof that the Hopi people have fulfilled their Covenant. The Hopi ancestors buried in the area continue to inhabit the land, and they are intimately associated with the clouds that travel out across the countryside to release the moisture that sustains all life.”

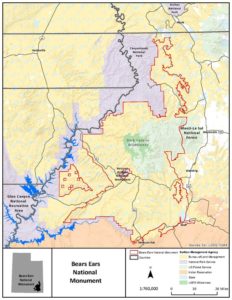

The deeply felt relationship of tribes in the Southwestern region to a larger regional landscape is a major reason that the councils of the tribes and pueblos sought the creation of an extensive monument. Archeologists have noted that that there are at least 100,000 sites in the region, including not only settlements but also the migration routes and pilgrimage trails referenced in the letter from the Hopi tribe. 121 archeologists supported and lobbied for the designation of a national monument covering these sites. The proposed monument was designated by President Barack Obama as the 1.3 million acre Bears Ears National Monument in 2016. Just one year later, the monument was reduced by 85% by President Donald Trump.

United States Forest Service map of Bears Ears National Monument December 31, 2016

The legality of the Bears Ears National Monument reduction is currently being challenged in federal court. Pressure by energy interests is thought to be a major reason that the current administration reduced the size of the monument: in addition to being rich in cultural resources the area also contains oil, coal, and uranium.

Contrast the Site-Oriented Legal Opinion

In March 2018, U.S. District Court for the District of New Mexico Judge James O. Browning indicated in a lengthy memorandum that he considered the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to have failed to fully comply with the National Historic Preservation Act. Groups opposing reduction of the size of the monuments were cautiously encouraged. (See Cultural Property News, BLM Failed to Comply with National Historic Preservation Act, April 15, 2018)

However, Judge Browning issued an order soon after, on April 25, 2018, that focused on BLM’s general compliance with the 1966 National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA). (See Greater Chaco Leases OK’d: Natives, Environmentalists Stunned, April 26, 2018, Cultural Property News, published in social media as Judge in Chaco Canyon Drilling Case Dismisses Suit)

Central to Judge Browning’s decision was the 2014 State Protocol Between the Bureau of Land Management and the New Mexico State Historic Preservation Officer Regarding the Manner in which BLM will meet its responsibilities under the National Historic Preservation Act in New Mexico. According to Browning the protocol indicates that “a project’s adverse effect on an archaeological site is limited to whether the project could physically destroy or damage the archaeological site. See 2014 Protocol at 30 (A.R.0169242)” ( DINÉ CITIZENS AGAINST RUINING OUR ENVIRONMENT; SAN JUAN CITIZENS ALLIANCE; WILD EARTH GUARDIANS; And NATURAL RESOURCES DEFENSE COUNCIL V. SALLY JEWELL, 1:15-cv-00209-JB-LF, p. 121)

The judge then opined that “Such a limitation makes sense, as the archaeological site’s historical value stems from the historical data recoverable from the location and not the historical property’s setting or feeling associated with it.” (Id., p. 121)

Tribes, Archeologists, the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (ACHP), and Even the National Park Service Disagree

Cedar Mesa Monument in Bears Ears National Monument, August 4, 2012, US Bureau of Land Management.

“Cultural Landscapes”, their relationship to archeological sites, and the cultural communities associated with those sites and landscapes through the millennium have been an ongoing conversation in historic preservation circles.

On the Federal policy level, the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (ACHP) – an advisory council to the President and Congress on preservation issues regarding our nation’s heritage, established by the 1966 National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) – has been in consultation with tribes to define Native American cultural landscapes and include them in NHPA Section 106 decision making and the tribal consultation process for nearly a decade.

According to the ACHP website “Landscapes can be defined as large-scale properties often comprised of multiple, linked features that form a cohesive area or place. They have cultural and historical meanings attached to them by the peoples who have traveled, used, and interwoven these places into generations of practice. “

An example of this is quoted above in the letter from The Hopi Tribe to Utah’s congressional delegation. Like the Hopi, the other tribes and pueblos in the American Southwest – The Navaho, Zuni, Acoma, Jemez, Laguna, Ute, Ysleta del Sur Pueblo, and others – all have similar relationships with the cultural landscape of the Four Corners region. The oral traditions and narratives of these groups as well as archeological findings and limited genetic research, link these tribes to ancestors who lived throughout the Four Corners area – relationships to the cultural landscape going back over 12,000 years, according to the tribes.

In recognition of these relationships, in November 2011, the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (ACHP) launched a Native American traditional cultural landscapes initiative and adopted an action plan. The plan calls for the ACHP and the Department of the Interior (DOI) to promote recognition and protection of Native American traditional cultural landscapes on the federal, state and local levels and “to address the challenges of the consideration of Native American traditional cultural landscapes in the Section 106 review process as well as in National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) reviews.”

The ACHP is the only entity with the legal responsibility to encourage federal agencies to factor historic preservation into federal project requirements.

Recognizing the Cultural Landscape.

The U.S. National Park Service recognizes the relationship between cultural landscape and historical value. The Chaco Culture National Historical Park website states, “The distinctive architecture of the Chaco civilization was “oriented to solar, lunar, and cardinal directions. Lines of sight between the great houses allowed communication. Sophisticated astronomical markers, communication features, water control devices, and formal earthen mounds surrounded them. The buildings were placed within a landscape surrounded by sacred mountains, mesas, and shrines that still have deep spiritual meaning for their descendants.”

It appears that Judge Browning chose not to consider these relationships when deciding on the Chaco case. Likewise, the current administration seems unwilling to listen to the counsel that Native American tribes and pueblos had given to the Federal Government that contributed to the Bears Ears National Monument designation.

Bears Ears National Monument, Utah, By US Bureau of Land Management, via Wikimedia Commons.

Bears Ears National Monument, Utah, By US Bureau of Land Management, via Wikimedia Commons.