“In mediaeval Hebrew, Geniza, or Beth Geniza, designates a repository of discarded writings. For just as the human body, having fulfilled its task as container of the [heavenly] soul should be buried, i.e. preserved to await resurrection, thus writings bearing the name of God, having served their purpose, should not be destroyed by fire or otherwise, but should be put aside in a special room designated for the purpose or in a cemetery.”

S.D. Goiten, The Documents of the Cairo Geniza as a Source for Mediterranean Social History, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 80, No. 2 (Apr. – Jun., 1960), pp. 91-100.

A report in VIN News this March described the discovery of a storehouse of religious, family, and economic records of unknown date by Cairo’s Jewish community while they were working to clean a long-neglected Jewish cemetery. Such archives, known as Geniza, are very rare. Often dating back centuries, they are primary sources for the history of Jewish communities in the Middle East.

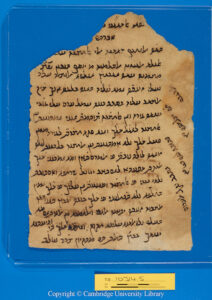

Letter (T-S 10J14.5) Recommendation by Moses Maimonides to a judge in a provincial town. 1235 CE, Donated by Dr Solomon Schechter and his patron Dr Charles Taylor in 1898 as part of the Taylor-Schechter Genizah Collection. © Cambridge University Library.

According to reporter Roi Kaisos, when Egyptian officials learned of the discovery, employees of the Antiquities Authority “broke into the cemetery… and began dumping the contents of the Geniza into dozens of plastic bags.” The Antiquities Authority staff spent 48 hours simply loading everything in the Geniza onto a truck without examining what they were tossing into bags. Antiquities Authority officials ignored protests by members of the Jewish community, who pleaded that at the least, a rabbi should be present to oversee the dismantling of the relics of their community.

Kaisos writes that the Cairo Jewish community has been unable to find out where the Geniza records were taken or what their fate will be. Community representatives went to the U.S. Embassy in Cairo to to try to enlist its assistance in obtaining information from the Antiquities Authority. The community has stated that they only wish to be involved in the Geniza’s preservation and care. They say that the Geniza should remain in Egypt but asked that it be accessible to the community. So far, they have received no response from the Egyptian government and the Geniza’s whereabouts is unknown.

Rabbinic law prohibits the destruction of old books, documents, and letters that contain the name of God; such texts must be either buried with the respect offered a person, as Torahs are, or preserved in a Geniza. While many Geniza documents are religious texts and commentaries, Geniza archives can be incredibly varied. They contain not only the records of politics and the actions of rulers as experienced by Jewish communities but also highly personal documents; they are an immediate, direct window into the past, sometimes stretching back a thousand years. Family, business, and community relationships can be seen through thousands of personal communications, detailed marriage and divorce records, in the letters sent home by distant traders and the negotiation of property and business contracts.

Geniza records have been essential to our understanding of domestic and international trade in the ancient world. For example, the details they contain have enabled researchers not only to understand the routes and patterns of trade and international rates of exchange. They also helped to identify the internationally valued textiles that were the most important commodity in ancient trade, and to know what type of fabrics a bride or a merchant or a prince wore in the eleventh century, what distinguished the cloths, where they came from, and what they cost in India, Baghdad, or Andalusia.

Geniza records were irreplaceable sources for some of the greatest modern historians of the medieval world, such as the scholar S.D. Goiten. They contain an extraordinary variety of documents illuminating the lives of ordinary people where historical records are otherwise unavailable.

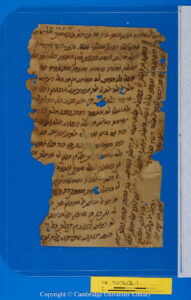

Letter (T-S 10J18.1) to Maimonides from his sister Miriam. 12th C. © Cambridge University Library.

Documents from Egyptian Genizas dating to the medieval period are now stored in libraries around the world. The collection of Geniza records began in earnest in the 1890s when a quantity of Geniza documents from Cairo were collected in the Bodleian Library at Oxford University and at the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York in 1896. Dropsie College in Philadelphia and the Freer Gallery at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington have smaller, but important collections.

The largest repository of Geniza records in the world is presently in the Taylor-Schechter Cairo Genizah Collection at Cambridge University Library. The collection is from the Ben Ezra synagogue of Fustat, in Old Cairo. In 1896-97, Cambridge scholar Dr Solomon Schechter learned of the Ben Ezra Geniza. He received the permission of its Jewish community to take it, under the supervision of their rabbi, to bring it to England and preserve it. He brought 193,000 books, texts, and back to Cambridge. The library is now in the process of digitizing the entire collection; more than 18,000 documents are currently available online.

Many Geniza documents make fascinating reading. As Goiten described a single letter in the 1960 article cited above:

“Thus the MS. T. S. 18 J 4, f. 18, represents a business letter sent from Aden to India, to a Jewish merchant from Tunisia, who ran a bronze factory and did other business out in that distant country. The recipient, having stayed a long time in India, returned to Aden in the autumn of 1149, but remained there and in the interior of Yemen for another three years; then, he had to make the long journey through the Red Sea, the terrible desert between it and the Nile river, and, finally, on the Nile from Upper Egypt to Cairo. Despite the humidity of the climate of India and Aden and the hazards of the journey on sea and through the desert – and the more than eight hundred years which have elapsed since it was written, the letter is in perfect condition, with even the smallest dot or stroke clearly discernible.”

Rescuing books from the basement of Iraqi secret police office, courtesy Dr. Harold Rohde. https://www.ija.archives.gov

The seizure from the Cairo cemetery appears disturbingly similar to the seizure of an 18th-20th century repository from a synagogue in Iraq by the secret police of Saddam Hussein. That collection was later discovered in a flooded basement in Baghdad and carefully restored by the U.S. National Archives. Since there is no longer a Jewish community in Iraq, this collection of mostly family and personal records, known as the ‘Iraqi Jewish Archive’ is claimed by both the Iraqi Jewish community in the diaspora and the government of Iraq.

Whether this most recent Cairo discovery is of ancient or relatively modern date, it is hoped that the Egyptian authorities will make the Geniza records taken by force from the cemetery available to students and scholars. Access should not be denied to the tiny Cairo Jewish community – and international pressure may help to ensure its preservation in the custody of the community to which it belongs.

Related:

Will Iraqi Jewish Heritage Stay in U.S.? CPN, August 10, 2018

US Rescue of Iraqi Jewish Archives Imperiled, CPN, October 2, 2017

After forcing entry to a Cairo Jewish cemetery, Egyptian Antiquities Authority Authority piles bags filled with the contents of the Geniza onto a truck. Roi Kaisos, VIN News.

After forcing entry to a Cairo Jewish cemetery, Egyptian Antiquities Authority Authority piles bags filled with the contents of the Geniza onto a truck. Roi Kaisos, VIN News.