Benin and gone.

Edo people, Benin, Queen Mother Pendant Mask: Iyoba, 16th century

Collection Metropolitan Museum of Art, Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Gift of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1972

Every few weeks, a fresh announcement appears – another museum is repatriating or committing itself in principle to returning a Benin bronze to Nigeria. There is a strong consensus among museum professionals that the bronze[1] and ivory objects looted by British troops in 1897 from the palace of the Oba of Benin should be returned.

The Benin Dialog Group (BDG), made up of Western museums and their Nigerian cultural partners, was established a decade ago as a forum to work collaboratively toward a permanent display of Benin works of art in Nigeria. In 2017, plans were announced for a new museum in Benin City designed by British-Ghanaian architect David Adjaye. The museum, to be known as the Edo Museum of West African Art (EMOWAA), would also be a cultural center, a school for artists, and an active archaeological site. If the bronzes were returned, there would be a worthy place for them.

(See Nigeria Welcomes Future Edo Museum of West African Art (EMOWAA), Cultural Property News, January 20, 2021 on the work of the Benin Dialog Group and the designs for the EMOWAA.)

Where will the ‘bronzes’ go and who will control them?

But EMOWAA is still a “vision.” It isn’t being built yet and the most positive reports say its opening is delayed until 2025. The Nigerian government, the Edo State Government, and the Oba Ewuare II, traditional ruler of Benin City, each say that they have the ultimate decision about where returned artifacts will be housed – and who will control them.

Godwin Obaseki, the charismatic governor of Edo State, acknowledges that repatriation of artworks is traditionally a national government to national government process, but continues to urge the importance of a Benin City locale for returned objects. This is not only because of the artworks’ historical ties to the Oba’s court and Benin City; the museum could also spur development and bring tourists to the impoverished region.

David Adjaye, Design for Edo Museum of West African Art, Courtesy Adjaye Associates.

Governor Obaseki, a skilled negotiator and businessman, has brought together Nigerian and foreign partners in an Edo Museum of West African Art Trust, to be funded by foreign donors and hold returned objects from Western museums. The existence of a Western-modeled, professional museum managed by an independent trust that would take responsibility for the returned objects is an attractive concept for Western museums concerned about the security of Nigerian museums and the safety of the bronzes, but has less appeal for the Nigerian government. Yet should the Nigerian Commission for Museums and Monuments (NCMM) and National Museum of Nigeria let an independent trust manage its national heritage?

David Adjaye, Design for Edo Museum of West African Art, Courtesy Adjaye Associates.

The Oba of Benin claims the Benin Bronzes as well. Many in Edo State believe that “the Oba of Benin is next to God,” a sentiment that Oba Ewuare II, a power player in politics in Edo State, would not deny. The current traditional ruler of Benin wants his ownership recognized and the bronzes to be held by his family in a ‘royal museum’ in a design similar to his palace and under their control. In May 2021, the Oba issued a statement ‘disowning’ imposters who claim any rights over the objects being returned and warning Enotie Paul Ogebor, who is in partnership with Godwin Obaseki in various projects, against his “unsolicited activities.”

“For avoidance of doubts, His Royal Majesty, Omo N’ Edo Uku Akpolokpolo, Oba Ewuare II, Oba of Benin remains the legitimate custodian of all insignia, symbols and such other artifacts depicting the rich cultural heritage of the Benin people.”

According to the statement, the Oba of Benin and the Benin Traditional Council, “has set up a very robust framework and body corporate to midwife and coordinate all efforts aimed at retrieving the looted and stolen artifacts from all over the world.”[2]

“The issue of ownership should never be in doubt,” says Charles Edosowan, a senior advocate and Benin chief, speaking recently on Nigerian television about the inalienability of the bronzes from the ruling family of Benin and their emotional and spiritual ties to the Oba’s kingship. While acknowledging that it is the job of the federal government to negotiate with foreign parties, Edosowan made clear the Oba’s expectation that the federal government would eventually deliver them to his control and that his own Benin royal museum – similar in construction to his palace – will be built to house them.

Benin Dialog Group meeting at the Nationaal Museum van

Wereldculturen,

The Netherlands, 19 October 2018.

While expressing great respect for the traditional status of the Oba, Nigeria’s Minister of Information and Culture Alhaji Lai Mohammed says that Nigeria’s federal government is the only proper recipient and custodian of the retuned bronzes. The Nigerian government is the only party capable of the government-to-government negotiations with cultural ministers in foreign nations. Although members of the Oba’s Court and Governor Obaseki have participated in the Benin Dialog Group and been involved in turnover ceremonies and celebrations of return in Nigeria, the objects all remain under Nigerian government control. In July 2022, at a tour of the Benin objects in the British Museum, Lai Mohammed thanked Curator Sam Nixon and Keeper Lissan Bolton and the museum for caring for the bronzes for so long, but after the meeting stated:

“Before now, they said we did not make a demand, but in October last year, almost nine months ago we made a formal request for the return of the artefacts especially the Benin bronzes for which we have not got any response… We also made it clear to them that they cannot hide under legislation and no Act of Parliament will make what you have stolen to become yours.”

Flood of returns.

Museum donors are moving faster to return objects than the Nigerian government is to provide a home for them. Some museums have already returned objects to the NCMM while others have legally transferred ownership to the Nigerian government, sometimes with agreements to retain some objects on long term loan.

Bust of Queen-Mother Idia, Benin, Nigeria, Humboldt Forum, Berlin, Germany.

Jesus College, Cambridge returned its famous bronze cockerel in the first public return of an object to Benin in October 2021; the same month the University of Aberdeen turned over a bronze head of an oba. Then the Church of England, which owns several bronze Benin sculptures that it was given 40 years ago, announced that it would return them. Then in November 2021, the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris returned 26 objects.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York transferred three Benin objects to the NCMM at the end of 2021. Glasgow Museums announced the return of 17 Benin bronzes on April 14, 2022. The Denver Museum of Art, which holds a number of artifacts from Benin, deaccessioned one dating to the 1897 punitive expedition in May 2022, while holding others of later date.

Also in May, a survey by the Washington Post found that 16 other U.S. museums had plans to return objects to Nigeria. In June, the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC voted to return 29 Benin bronzes from the National Museum of African Art. In July, Germany delivered two bronzes to cultural authorities while announcing the legal transfer of 1100 more objects to Nigeria, whose status as returns or loans back to German museums would later be negotiated. The Horniman Museum and Gardens in London announced the return of 72 artifacts this August.

The Weltmuseum in Vienna, a member of the Benin Dialog Group, holds some 173 Benin artifacts, but these were collected long before by the Hapsburgs. There are 136 Benin artifacts at Cambridge University’s Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology and about 100 at the Pitt Rivers collection at Oxford University.

The British Museum hold 928 objects. The BM has worked for years in active partnership with Nigeria on conservation, display, training, and even archaeological work, but has not yet resolved the ownership status of the objects it holds. This is due, at least in part, to legal restrictions on deaccession that are now potentially changing.

(See UK Charity Act Opens Door to Restitutions, Cultural Property News, September 26, 2022.)

The 1897 raid.

In early 1897, over one thousand British troops captured, burned and looted what is now Benin City, bringing to an end the Benin Kingdom, one of the oldest and most highly developed West African civilizations. The punitive expedition was launched ostensibly in retaliation for an attack that killed unarmed British trade envoys and their accompanying bearers.

Tensions had been building between the regions numerous kingdoms and British traders for years. The British had been eyeing its resources and wealth for decades and viewed the dominant role of the Oba (Divine King) of Benin as a hindrance. Pressure mounted regarding a trade agreement that the Oba refused to sign. British Consul-General James Phillips perceived noncompliance with the accord as a hostile act. He informed the Oba that British trade envoys would be arriving to persuade him to sign. The Oba attempted to delay the visit, saying that an important religious event was pending. A delegation of nine white men set off with 250 African bearers accompanying them. Although the Oba does not appear to have been directly involved in ordering hostilities, his surrounding sub-chiefs ambushed the expedition, killing seven of the nine envoys and most of the bearers and provoking the punitive military expedition in 1897.

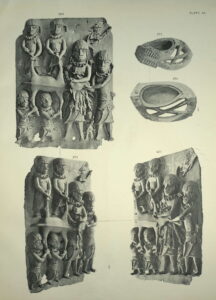

Human Sacrifice. What the raiding troops found on their way into Benin City.

Illustration from Antique works of art from Benin (1900) by A. Pitt-Rivers. Public domain.

What the British troops of the punitive expedition found when they arrived at Benin City confirmed the British public’s most gruesome fantasies of the ‘barbarism’ of the oba and his court.

The expedition’s doctor, Felix Norman Roth, described the entry of the first troops into Benin City.

“As we neared Benin City we passed several human sacrifices, live women-slaves gagged and pegged on their backs to the ground, the abdominal wall being cut in the form of a cross, and the uninjured gut hanging out. These poor women were allowed to die like this in the sun. Men-slaves, with their hands tied at the back, and feet lashed together, also gagged, were lying about. As our white troops passed these horrors one can well imagine the effect on them — many were roused to fury, and many of the younger ones felt sick and ill at ease. As we neared the city, sacrificed human beings were lying in the path and bush — even in the king’s compound the sight and stench of them was awful. Dead and mutilated bodies seemed to be everywhere — by God! may I never see such sights again!”

“In the king’s compound, on a raised platform or altar, running the whole breadth of each, beautiful idols were found. All of them were caked over with human blood, and by giving them a slight tap, crusts of blood would, as it were, fly off. Lying about were big bronze heads, dozens in a row, with holes at the top, in which immense carved ivory tusks were fixed. One can form no idea of the impression it made on us. The whole place reeked of blood. Fresh blood was dripping off the figures and altars (months afterwards, when we broke up these long altars, we found that they contained human bones). Most of the men are in good health, but these awful sights rather shattered their nerves.”

Illustration from Antique works of art from Benin (1900) by A. Pitt-Rivers. Public domain.

“The king’s house is rather a marvel — the doors are lined with embossed brass, representing figures, etc., while the roof is formed of sheets of muntz metal, and the rafters to support the same artistically carved. In front of the king’s compound is an immense wall, fully twenty feet high, two to four feet thick, formed of sun-dried red clay. This wall must be a few hundred yards long, and at each end are two big ju-ju trees. In front stakes have been driven into the ground, and cross-pieces of wood lashed to them. On this frame-work live human beings are tied, to die of thirst or heat, and ultimately to be dried up by the sun and eaten by the carrion birds, till the bones get disarticulated and fall to the ground. There were two bodies on the first tree and one on the other. At the base of them the whole ground was strewn with human bones and decomposing bodies, with their heads off. Three looked like white men, but it was impossible for me to decide, as they had been there for some time; the flesh was off their hands and feet, and the heads had been cut off and removed. The bush, too, was filled with dead bodies, the hands being tied to the ankles, so as to keep them in a sitting posture. It was a gruesome sight to see these headless bodies sitting about, the smell being awful. All along the road, too, more decapitated bodies were found, blown out by the heat of the sun; the sight was sickening. To-day was occupied in blowing down these ju-ju trees.”

(Henry Ling Roth and Felix Norman Roth authored “Great Benin; its customs, art and horrors,” 1903. Felix Norman Roth worked with the medical service of the Niger Coast Protectorate. His brother Henry Ling Roth was an anthropologist of the early type.)

Given this reporting, it’s not surprising that the British public did not question the taking of the Benin bronzes, which were advertised as being sold to pay for the cost of the punitive expedition.

Britain’s sale of the bronzes.

Palace of Benin, destroyed by fire. Photo 1897.

At the end of the ransacking of Benin City the British left with over 2,500 artifacts, primarily of ivory and brass/bronze. Most of these pieces were from the royal palace and many served as a record of royal history. Some of these items were auctioned to pay for the expedition, some were gifted to individuals in the British military, and almost a thousand were accessioned to the British Museum in London. The Pitt Rivers Museum, at Oxford University, holds nearly one hundred works of Benin art, mostly purchased by General Pitt-Rivers at the time. Thirty-nine of them, taken from Benin City by the British Chief of Staff of the Punitive Expedition, Captain George Leclerc Egerton, are on long-term loan from the Egerton family. German museums were the most enthusiastic buyers of the Benin bronzes when they were auctioned, purchasing more than any other institutions.

Benin bronze head of an oba or king, circa 1650. Presented to Queen Elizabeth II by General Yakubu Gowon, Head of the Federal Military Government of Nigeria, during his State Visit to the United Kingdom, 12-15 June 1973. Courtesy Royal Collection Trust.

The exceptional quality of these masterworks of African art has encouraged their continuing circulation into smaller collections and individual objects from Benin may be found in many dozens of museums around the world. Some of the British Museum’s bronzes were considered “duplicates” and were sold in the mid-20th century. The British Museum sold 4 Benin bronze plaques to a London gallery for £1100 pounds in order to determine a general valuation, but then sold at least 27 more to the Nigerian government for as little as £75 pounds each, according to a 1972 report. A number of these disappeared from the National Museum in Lagos and reappeared on the market, including two plaques acquired by a New York collector and donated to the Metropolitan Museum in 1991, which were recently returned to Nigeria by the Met.

It is not known how many of the Benin objects in Nigerian museums at the time of independence are still located there. In 1973, displeased with the quality of a replica he had ordered as a state gift for Queen Elizabeth, the then Nigerian head of state simply took one from the Lagos National Museum and presented it to her. It is still in theWindsor palace collection.

Keeping Benin’s art on view in world museums.

Benin bronze plaques displayed at British Museum. Photo Joyofmuseums, 16 July 2018, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

Some objections to blanket returns of all objects from Benin have come from specialists in the field who are concerned about preservation of objects or their access to global scholars. Other questions are quietly being raised by museums that also feel an obligation to give an important place to African art in their collections and tell the story of Benin to a diverse and international public.

There is also an argument that including Benin materials and other fine works of art from Africa in museums around the world is key to giving it an equal place together with the most brilliant artworks of other past civilizations. Writing in The Atlantic, David Frum has pointed out that scholars and collectors had to battle for decades in the 20th century to gain acceptance for African art – to have great African art displayed in museums as the equal of art from anywhere else in the world, instead of being derided as ‘primitive’.[3]

While many people in the countries where Benin bronzes are held feel that justice requires their return, together with apologies for the brutal raid in which they were taken, others have argued that this is not the whole story.

Links between the Benin bronzes and the slave trade.

Benin, sculpture of a Portuguese soldier, bronze, Bode Museum, photo by Sailko CCA 3.0 unported license.

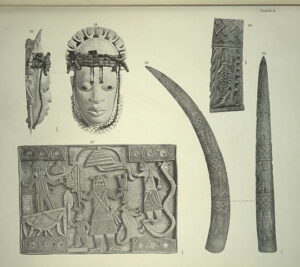

The Benin bronze plaques themselves were made from the copper used to buy and sell slaves in the region. Brass bracelets brought by Portuguese traders known as ‘manillas’ were the currency exchanged for slaves. Portuguese traders are depicted along with Benin elite and warriors on the plaques, while the crescent shaped manillas with flaring ends, symbolic of material wealth, form a decorative pattern in the background.

The records of Portuguese traders provide clear evidence of the use of copper and brass manillas in the slave trade. Historian Toby Green, Professor of Precolonial and Lusophone African History and Culture at King’s College London has written:

“The key currency initially was copper, and imports grew rapidly. An early account described how copper was used in the first trade between the Bini [the inhabitants of the kingdom of Benin] and the Portuguese. The Portuguese bought enslaved persons from the Bini, Duarte Pacheco Pereira wrote around 1506, with each war captive selling for 15 manillas of copper. This, of course, was not very much, and documents from 1517 show that already the number required for the purchase of captives had risen to 57. By 1522, manillas were also being used to buy basic provisions in Benin, such as yams, wood and water, all of which were needed to feed enslaved persons on ships for the return voyage to the new sugar plantations of Sâo Tomé. Manillas would become a currency widely used throughout this part of West Africa long into the nineteenth century…”

“…So what on earth were the imported manillas used for? Beyond the melting down of copper for recasting in military hardware, as shields and helmets, Dapper’s compilation of existing accounts in the seventeenth century provides a significant clue. When describing the oba’s palace, he noted that it had innumerable courts and apartments, ‘containing within fair and long Galleries, one larger than the other, but all supported on Pillars of Wood, cover’d from the top to the bottom with melted copper, whereon are Ingraven their Warlike Deeds and Battels, and are kept with exceeding Curiosity’. In other words, quite a large part of the manillas would appear to have been melted down to construct the famous bronzes. Thus, what distinguished this use of currency from the use of gold in Europe and silver in China to accrue surplus value at this time was that Benin appears to have employed much of the new currency base to refashion self-images and identities.”[4]

Detail, Benin Bronze plaque depicting Chief Uwangue and Portuguese traders holding ‘manilla’, bronze bracelets used to purchase slaves; from the Horniman Museum collection to be sent to Nigeria. Courtesy Horniman Museum and Gardens, London.

According to the Oba Ewuare II Foundation publication, Benin Monarchy: An Anthology of Benin History:[5]

“Copper and brass were originally imported from the mines to the south of the Sahara, but towards the close of the fifteenth century, migrating Arab tribes penetrated inland up to the territory of present-day Chad and broke the traditional trade routes heading towards West Africa The role of metal importers to the kingdom of Benin was taken over by the Portuguese, who traded imported metal in the form of bracelets (manillas) for slaves, spices, and ivory in the sixteenth century.”

Restitution Study Group says the full story must be told.

An organization of African American human rights activists, the Restitution Study Group, believes in the importance of presenting the Benin bronzes – wherever they are located – as part of a more complete narrative that includes the Benin kingdom’s role in the slave trade. The Restitution Study Group is a U.S. nonprofit that has worked for years to raise awareness of the continuing impact of slavery on peoples of the United Kingdom, Caribbean Commonwealth nations and United States whose ancestors were enslaved.

Benin plaque depicting the head of a Portuguese soldier with a background of manillas, copper bracelets used in the slave trade. 16-17th C. Photo by Sailko, GNU free documentation license.

In its correspondence with museums that have announced returns of Benin Bronzes, the Restitution Study Group requests repatriating museums to hold back returns until there is a guarantee that the truth about the manillas depicted on the bronze plaques and the Benin kingdom’s history of human sacrifice and its slave trade will be told in Nigerian and all other museum exhibitions.

The Restitution Study Group group, led by Executive Director Deadria Farmer-Paellmann, objects to the return of the Benin bronzes made with the manillas from the 1500’s through the 1800’s. Instead, says Farmer-Paellmann, the bronzes should be held in trust and ownership should be jointly vested in the descendants of the thousands of men, women and children captured and sold by the slave-trading kingdom of Benin. She notes that 82% of Jamaican slave descendants have DNA from Nigeria, and 93% of African American slave descendants have Nigerian DNA.

In an August 15, 2022 letter directed to the UK’s Charity Commission, whose permission was being sought for transfer of the 72 Benin objects held by the trustees of the Horniman Public Museum and Public Park Trust, Farmer-Paellmann wrote:

“We want to secure access to these relics for our children and families at museums in the UK and USA… The Kingdom of Benin through Nigeria would be unjustly enriched by repatriation of these relics they made with manilla currency: they were paid to raid villages with illegal guns and other weapons, steal women, children and men, sell them into the Transatlantic slave trade, and sometimes kill them in ritual sacrifices.”

“At a time when DNA descendants are engaged in efforts to secure justice for slavery, there has been no major media outlets reporting on the fact that most of the Benin Bronzes are made with metal manillas the Kingdom of Benin was paid for selling humans into the Transatlantic slave trade. Extensive scholarship exists verifying this fact. It is doubtful that any petition you receive to transfer the Benin bronzes will mention the slave trade origin of the metal in the Benin bronzes.”

“Black people do not support slave trader heirs just because they are Black… Nigeria and the Kingdom of Benin have never apologized for enslaving our ancestors. They have no remorse and yet they claim to be the victims. It is true there was one Punitive Expedition in 1897, but it ended the sale and sacrifice of enslaved people who suffered 300 years of Punitive Expeditions at the hands of the Kingdom of Benin.”

Waist pendant plaque, Benin Kingdom, court style, Edo peoples,, Benin City Nigeria 18th century, ivory, courtesy Dallas Museum of Art .

The Restitution Study Group has submitted similar letters to German cultural authorities including Dr. Hermann Parzinger of Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz, to museum directors and state and federal ministers. In correspondence with Ngaire Blankenberg, newly appointed director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art and with other museum directors, the Restitution Study Group has urged further due diligence research before sending Benin bronze materials to Nigeria.

Within eleven days of her appointment in October 2021, Ms. Blankenberg had directed the removal of the National Museum of African Art’s Benin bronze plaques from display and announced the museum’s intention of returning them. At the time, she told ArtNews that “it is very important for us at NMAFA that the Benin Bronze process be seen within a much wider context and strategy. Our process of trust-building with African and African diasporic peoples starts with decolonization – proactively evaluating the impact of unequal power relations in our sector, looking carefully and in many instances changing how we hire, document, conserve, interpret, program – and yes it may also include repatriation.” Then in March 2022, the Smithsonian’s Board of Regents announced that “most” of its 39 bronzes would be deaccessioned and returned under an agreement with Nigeria’s NCMM, but that some would be brought back as long term loans for public display. According to email correspondence seen by Cultural Property News, Ms. Blankenberg informed Farmer-Paellmann on July 29, 2022 that the decision over the return of the Bronzes was final.

[1] Though these objects, now found in museums all around the world, are often called the “Benin Bronzes,” this is actually a misnomer as they are made of many different materials including ivory, cloth and wood; and the items that are made of metal are actually not bronze, but an amalgamation most closely resembling brass.

[2] Stolen Artifacts: Oba of Benin disowns ‘impostors’, Premium Times, May 11, 2021, https://www.premiumtimesng.com/regional/south-south-regional/460954-stolen-artifacts-oba-of-benin-disowns-impostors.html

[3] David Frum, Who Benefits When Western Museums Return Looted Art?, The Atlantic, September 14, 2022, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2022/10/benin-bronzes-nigeria-return-stolen-art/671245/.

[4] Toby Green, A Fistful of Shells: West Africa from the Rise of the Slave Trade to the Age of Revolution, University of Chicago Press, 2019, pages 165-166.

[5] Oba Ewuare II Foundation publication, Benin Monarchy: An Anthology of Benin History, Benin Traditional Council Editorial Board, 2018, p 205.

Benin plaque depicting a Portuguese soldier with a background of manillas, copper bracelets used in the slave trade. 16-17th C. Photo by Sailko, GNU free documentation license.

Benin plaque depicting a Portuguese soldier with a background of manillas, copper bracelets used in the slave trade. 16-17th C. Photo by Sailko, GNU free documentation license.