“All armed groups have targeted historic sites one way or another since March 2015. However, the most blatant and systematic of them is without any doubt, the Saudi coalition, and they are the ones who have made the most irreparable damage in Yemen.” American archeologist Lamya Khalidi, The New Arab, March 26, 2018

A US-Yemen agreement to block all cultural artifacts from Yemen – based upon erroneous and misleading data – is well underway. The questionable data appears designed to increase the scope of future import restrictions to advance Yemeni government claims of blanket ownership to all ethnographic and antique objects, including the cultural heritage of religious minorities driven out of Yemen.

Proposed U.S. responses promoted by anti-trade advocacy groups are raising serious questions about the agenda behind unsupported claims that Yemeni art is being looted– when the evidence shows that rampant destruction, not looting for sale, is the problem.

State Department’s Mistaken Focus on Market

Why are the Department of State, through its sponsorship of the Yemen Red List, and advocacy groups such as the Antiquities Coalition, proposing that destruction is the result of a supposed $8 million dollar trade in antiquities taken from Yemen over the last ten years, when official U.S. import data does not show that at all? How can looting be market-driven when there is no U.S. market, except for well-provenanced artworks and Jewish manuscripts?

A blind child carries a dove at a protest against the attack on the al-Nour Center for the Blind in Sana’a, Yemen, Jan. 10, 2016. Students say neither the school, nor themselves, have taken any side in the war. (A. Mojalli/VOA)

Some have postulated that the drive for a cultural property agreement with Yemen blockading imports is simply to add another brick to the U.S. wall against importing ethnographic and ancient art from around the world. This wall is certainly getting higher, with 17 countries already subject to import restrictions, more pending from 2018 and 5 others expected in 2019.

Others have concerns that moves to include Yemen in cultural property agreements will create a smokescreen protecting the U.S. from accusations of supporting the Saudis deliberate bombings of heritage sites. American Jewish groups also see a future Yemen agreement as reinforcing repressive Middle Eastern governments’ claims to the heritage of minority religious groups. (See: 18 Jewish Organizations Protest MENA Nationalization of Heritage to State Department, Cultural Property News, December 20, 2018.)

A Department of State official announced in 2018 that five additional cultural property agreements with Middle Eastern and North African nations were in the works for 2019. Egypt, Syria, Iraq, and Libya imports of ancient and ethnographic art are currently restricted, and a request for import restrictions from Jordan was announced Jan 31, 2019. Ultimately, the intent is to have the entire region covered by import restrictions.

A more sinister aim, however, is to obscure the fact that indirectly, even if unwillingly, the U.S. government shares responsibility for the ongoing cultural devastation.

The Yemeni heritage crisis is the result of bombing campaigns targeting museums and historic sites. The destruction is not a new problem; it has been ongoing throughout the war. And too often, the destruction is caused by U.S. allies using U.S. supplied weapons.

Digital Documentation is Key

U.S. and U.K. art trade groups are in favor of alerting the public to the risk that stolen artifacts may circulate globally, and for ensuring that the photos and descriptions of objects from Yemeni museums are well-known to art dealers, collectors and museums – although today, artworks without provenance are virtually unmarketable in the West.

Information on Yemeni museum holdings are available through the work of CSAI/DASI, the Digital Archive for the Study of Pre-Islamic Arabian Inscriptions centered at the University of Pisa. Any objects taken from Yemen’s cultural sites, monuments, and institutions are already illegal to sell, and must be tracked down and returned to Yemen when it is safe to do so. Fortunately, the digitization program will make this possible, not only in the U.S., but internationally.

Jewish Organizations Protest

Further, organizations representing the Jewish diaspora maintain that it is wholly unjustified to impose blanket restrictions on the circulation of lawfully owned objects from Yemen, or to grant the government of Yemen ownership and control over Jewish, Christian, Baha’i, and Hindu cultural objects belonging to minority religious communities. They have raised powerful arguments for limiting any future agreement to objects that actually have been looted, and for insisting that any agreement be limited by the criteria set by Congress.

A letter was sent on December 9, 2018 by 18 Jewish organizations to Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, asking that the State Department’s Bureau of Education and Cultural Heritage adhere “to the limitations set by Congress under the Cultural Property Implementation Act by denying broad, excessive import restrictions to nations that have neither valued nor cherished the ancient heritage of Jewish, Christian, and other minority peoples.”

Benayah ben Sa’adyah ben Zechariah. Yemen: 1469. Valmadonna Trust Library, MS 11. Courtesy Sotheby’s Inc.

Customs Data Contradicts Claims

Data from U.S. Customs raises serious doubts about allegations that marketable objects are being looted to be sold anywhere in the West, and both Customs and auction house records point to the lack of any U.S. market for Yemeni antiquities, outside of antiquities with a solid legal provenance. These include antique Jewish religious artifacts such as Torahs, and religious manuscripts such as those from the Valmadonna Trust Library that have been outside of Yemen for many decades. The destruction of Yemeni heritage is horrific and ongoing – but there is no evidence that it is market-driven.

The Limited Market for Art and Artifacts from Yemen

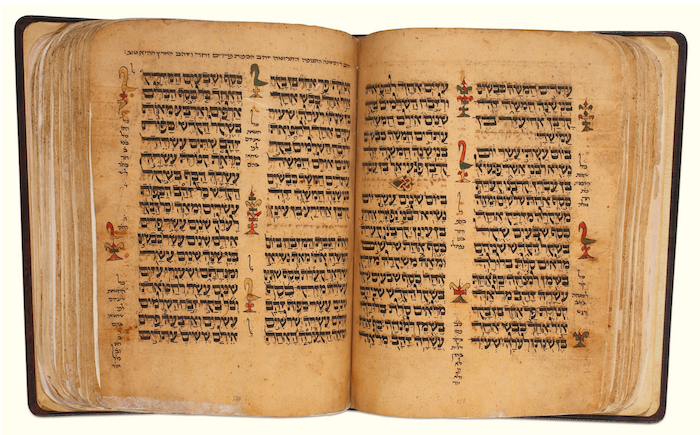

Moreover, the only significant sales of imported Yemeni artifacts in the last decade, are of objects collected long before the war began in 2015. The most valuable U.S. sales by far in the last decade came from Jewish libraries in Europe, including two Hebrew Bibles sold at Sotheby’s in 2015 from the Valmadonna collection in the UK, the finest private collection of Hebrew books and manuscripts in the world.

Yemeni Jewish necklace, collected 1980s.

The only other antiquities originating in Yemen for which there has been a market are the stone (and occasionally bronze) sculptures known as South Arabian, some of which originated in South Arabian lands that are presently part of the territory of the modern nation of Yemen, and others originating in present day Saudi Arabia. A summary of the auction sales for both Sotheby’s and Christie’s is linked. Four objects in ten years were sold at Sotheby’s New York, one in 2009, three in 2015, that is, before the war. Thirty-two sculptures were sold at Christie’s, almost all in 2009 and 2010, the last one in 2014, again, before the Yemen war began, and most from much older collections. The very limited art market for Yemeni antiquities is not interested in objects that might be looted.

As for the silver and base metal bead ornaments traditionally worn by Jewish brides, these are generally sold for silver weight, no more. They may be identified as from Yemen in U.S. Customs records, as is proper, but they most often come from Israel, to which most Yemeni Jews emigrated, or are already in circulation from the popular U.S. bead market of the 1970s and 1980s. There are only 50-some Jews remaining in Yemen, living hidden lives in fear of both government and rebels.

Both U.S. Allies and Rebels Are Bombing Museums and Historic Sites

On January 28, 2019, the Saudi state news agency SPA reported that Yemen’s director of the General Authority of Museums, Antiquities and Manuscripts Fayez Al-Dhibiani said Iran-backed Houthi fighters had stormed and were thought to have looted the Baynun Archeological Museum in Dhamar.

The collections from Baynun are also documented on the website of CSAI. Under U.S., U.K. and European laws, any object stolen from a museum collection is illegal to sell; no special cultural agreement is required. That the far larger archaeological collections in the Dhamar Regional Museum had been destroyed when the museum was flattened in a deliberate Saudi rocket attack in 2015 was not mentioned in the report.

U.S. archaeologist Lamya Khalida has described the complete destruction of the Dhamar Regional Museum, where she had worked documenting artifacts for years. She says the Saudi bombing resulted in the complete loss of 12,000 artifacts from 400 sites. She also said that the Saudis have ignored alarms raised by the U.S. State Department and a UNESCO no-strike list of heritage sites, public buildings and monuments. As quoted in the Irish Times, Khalida said, “While [Islamic State] and al-Qaeda have targeted historic sites, their damage was insignificant compared to what the coalition has done.”

According to a preservation program sponsored by Council of American Overseas Research Centers, the CAORC-Kaplan Responsive Preservation Initiative, Yemen’s General Organization of Antiquities and Museums has been working to find objects in the rubble of the Dhamar Regional Museum and to document and preserve the collections of the Baynun Museum, which it described in 2018 as threatened “by encroaching Al Qaeda forces and the possible onset of aerial bombardment.”

Violating Human Rights and Cultural Rights

Zinjibar, Museum, ZM-A 13=NAM 346=AM 737, photo courtesy DASI, Collection of the objects of the Zinjibar Museum.

CPN has reported on cultural destruction and violations of civilians’ human rights in Yemen by all parties in the war. (See Mwatana for Human Rights: Destruction of Yemen’s History, Cultural Property News, November 26, 2018 for an extensive list of sites and monuments destroyed and damaged by all sides in the war.) Organizations such as Mwatana for Human Rights have also described the perilous position of minority religious groups, which include Hindu, Baha’i, Christian and Jewish communities under dire threat. Yemeni monuments, ancient dams, and museums, and many of its unique architectural treasures, including traditional houses with Star of David decorations, have been deliberately bombed or burned in a campaign targeting noncombatants in its ancient cities. The same bombing raids have caused untold horrors for Yemen’s civilian population, leaving 75% of the population in need of humanitarian assistance, according to U.S. National Intelligence Director Dan Coats.

A U.S. cultural property agreement could force return of religious items to the Yemen government, which claims ownership of all antiques, despite having failed to protect the tiny, terrorized remnant of what was once a flourishing Jewish community. In 2018, nineteen Yemeni Jews left Yemen in a covert airlift for Israel; almost their only belonging was an 800-year-old leather Torah. They could take nothing from their homes. In Yemen, the government did not allow Jews to wear good or new clothes, or to carry the curved Yemeni daggers that are made by Jewish craftsmen. After they arrived with the community’s Torah, the Yemen government arrested a Jewish man and a Muslim airport employee, accusing them of removing government owned artifacts and demanding the Torah’s return.

Misleading Claims by the Government of Yemen and the Antiquities Coalition

An influential Washington, D.C. organization, the Antiquities Coalition, which urges an across-the board expansion of blockades on U.S. imports of Middle Eastern and North African art, has offered misleading statements regarding a supposed trade supporting terrorism many times over the years.

In an opinion piece for the Washington Post on January 1, 2019, Deborah Lehr of the Antiquities Coalition and Ahmed Awad Bin Mubarak, former permanent representative of Yemen to the UN wrote:

“There is good reason to believe that the United States is a destination for pillaged Yemeni artifacts, because it remains the largest art market in the world. Research by the Antiquities Coalition demonstrates that, over the past decade, the United States has imported more than $8 million worth of declared art and antiquities from Yemen. There is reason to suspect that the total is much higher. While it is impossible to know the true scale of the illicit trade, it is distressingly familiar, as plunderers across the region have seen museums and ancient sites as opportunities to raise easy money.”

Fact: According to U.S. Customs data, in the past decade, the United States has imported $703,495 of antique, ancient, and ethnographic objects that originated in Yemen. This number includes imports from Europe and Israel of Yemeni origin. Are Ms. Lehr and Awad Bin Mubarak suggesting that U.S. Customs is not competent to detect smuggling from Yemen? What is the reason to suspect that the total is higher?

The only way to get a number close to $8 million is to count all imports of goods from art to antiques to postage stamps under Harmonized Tariff Code 41320, that would include all such goods that originally came from Yemen at any point in history, and that entered the U.S. from any country from 2008 onward. Moreover, the total drops to $1.3 million for the last five years, and during the last two years the total was only a tenth of that. Shrinking numbers are not evidence of a growing problem or a need for emergency restrictions. (See below how the U.S. Customs ‘country of origin’ import documentation works and why this number pertains primarily to importation of antique goods from Europe.)

Statement by Deborah Lehr in NPR interview:

“We have evidence of al-Qaida raids on some of the museums in Yemen and we have evidence in Europe, even in Brussels, of dealers who have been selling al-Qaida Yemen’s sponsored antiquities… There’s definite evidence of ISIS benefiting. In a special forces raid of one of the complexes of essentially the person who was the chief financial officer of ISIS, we found receipts of about $5 million worth of antiquities over the course of a year that they had sold.” (starting at 2.15)

Fact: Wrong country, wrong numbers. The supposed evidence of ISIS benefitting was from a special forces raid in Syria, not Yemen, and was incorrectly used to claim, with respect to Syria, that ISIS was garnering huge profits from antiquities. Documents acquired by U.S. Special Forces in the May 2015 raid of Abu Sayyaf’s hiding place demonstrated that the only primary source documents “put the figures at around $4m a year and that includes money from mineral and metal extraction.” (See also, Bearing False Witness: The Media, ISIS, and Antiquities, Cultural Property News, December 1, 2017.) These claims have triggered another alarmist chorus in the press and in Congressional offices, despite their obvious factual flaws.

Statement by Lehr on how many antiquities have left Yemen in NPR interview:

“It was one of the centers of the spice and incense trade and in fact developed [as] the Manhattan of the desert, as a major trading center, with the first skyscrapers of the 16th century, and one of the first major dams in the 8th century B.C. All of these have been targeted for destruction and we’re losing significant amounts of what was really very rich history to these thieves.” (starting at .55)

Fact: Saudi Arabian forces bombed and destroyed the ancient Marib Dam in 2015.

Statement: from Lehr and Awad Bin Mubarak in the Washington Post opinion piece: “Three major museums — the Taiz National Museum, the Aden National Museum and the National Museum of Zinjibar — have been pillaged and largely cleared of their collections. “

1: Incorrect, the Taiz National Museum was not pillaged. The museum’s contents were destroyed, burning for two days after Houthi rocket shelling. Local fighters had been leaving their military vehicles in the museum compound; both sides blamed each other for triggering the attack. It held primarily Islamic manuscripts and antiques.

2: We can find no mention of pillaging or an attack on the National Museum of Aden. However, by August 2017, the Aden Military Museum (once a Jewish children’s school) had been damaged in fighting that drove the Houthi from Aden. (The National Museum of Aden is a different museum located in a colonial building, held the collection of Kaiky Muncherjee, a rich Indian trader living in Aden, who collected all kinds of antiques and knickknacks in the early 20th century, as well as a substantial collection of South Arabian statuary. Although it is described as having many of its objects “lost, stolen, or destroyed” after the civil war in 1994, the CSAI project, a joint Italian -Yemeni documentation project, photographed and recorded 195 inscribed objects from the collection of between 2006-2009.)

3: The National Museum of Zinjibar was looted in 2012, three years before the Yemen war began. It held fifteen ancient objects, all of which are documented in the CSAI database.

Statement by Deborah Lehr in NPR interview.

“They meet with sophisticated middle men and they’re being bought by collectors and others in major Western markets. Some of it is even showing up in the United States. These monies are going back and being used by the Houthis and other terrorist organizations in the region.” (starting at 1.55)

Fact: Customs Data Shows No Looted Items in U.S.

Contrary to claims made by the Antiquities Coalition and others seeking justification for a U.S.-Yemen cultural property agreement, U.S. Customs data shows no evidence for a U.S. market for looted Yemeni goods.

The U.S. Census Bureau is the agency tasked with collating and publishing all data on U.S. imports and exports. Despite the claims of the Antiquities Coalition, what import data tells us is very different. The listing of import data and values by the Census Bureau is based on the Country of Origin, not the country of export. In fact, the U.S. Census Bureau does not publish statistics based on the country of shipment.

Yemeni necklace of type worn by Jewish brides.

Thus, an object of Yemeni origin that had been in Europe or Israel for decades would still be entered into the US as from Yemen.

This has two effects.

- Items will be identified as from Yemen in US trade data even if they have actually been in a third country for many years.

- The most valuable objects from Yemen are Jewish Bibles and religious manuscripts. If a U.S.-Yemen agreement is made under the Cultural Property Implementation Act, community or individually owned objects of Jewish heritage that left Yemen long ago with Jewish owners could be subject to import restrictions, seizure on import, and return to Yemen unless there was proof of export from Yemen dating back a decade or more. Proof of export for many objects is unlikely to be available.

Correlating the import data with the auction sales of Yemeni artifacts imported into the U.S. from European collections, such as the Valmaddona Collection manuscripts, demonstrates that it is unlikely that even the very few U.S. sales of Yemeni origin articles over the last decade were imported directly from Yemen.

More Real Numbers

Other documentation of illegal trafficking from Yemen also shows it to be at a minor level. The World Customs Organization released a 249 page Illicit Trade Report in early February 2018, devoting many of its pages to examining the trade in cultural property – although compared to other forms of illegal trafficking, the cultural property segment was minuscule. A report specifically on Yemen’s illicit cultural property trade stated that Yemen Customs reported five seizures in 2016, resulting in the retention of over 110 individual cultural objects, including coins, statues and calligraphy. The goods were destined for East Africa and Jordan. All the items were in personal luggage stopped at the airport or on their way there, and clearly smaller items.

Yemen Finally Offers to Sign 1970 UNESCO Convention

The proposed blockade of all cultural artifacts from Yemen began as an effort to bypass normal review – setting a dangerous precedent that could impact U.S. cultural relations with many other countries. Since Yemen never signed the 1970 UNESCO Convention, which requires nations to commit to preserving their own heritage and helping to safeguard other nations’ art and artifacts, it raises questions about its performance of the international obligations that it avoided for almost 50 years by not signing. However, only UNESCO 1970 signatories can benefit from U.S. import restrictions under the Cultural Property Implementation Act, 19 U.S.C. §§ 2601-2613.

In January 2019, the government of Yemen indicated it willingness to sign UNESCO in a cabinet decision. The only apparent reason to sign UNESCO now is to enable Yemen to seek a blockade on its art and artifacts though the Cultural Property Advisory Committee at the U.S. Department of State.

Yet Yemen’s government has failed to protest the destruction of sites and monuments by its own allies.

The Destruction Continues

In September 2018, the International Red Cross said there had been 1800 airstrikes in the four-year long war, equivalent to one every 99 minutes, and that one third of the targets were civilian. Civilian deaths in Yemen surged after last June’s Saudi-led offensive, and fighting at the port of Hodeidah has also interrupted humanitarian aid, worsening famine conditions in much of the country. Targeting civilian sites also means destruction of heritage in Yemen, a country where ancient architectural traditions have been scrupulously preserved.

In an opinion piece for the New York Times in June 2015, archaeologist Lamya Khalida wrote:

“The desecration of these archaeological sites and monuments, as well as the architecture and infrastructure of Yemen’s historic cities, can be called only a targeted and systemic destruction of Yemeni world heritage. Yet it has not been named as such…The same obscurantist ideology by which the Islamic State justifies its destruction of cultural heritage sites appears to be driving the Saudis’ air war against the precious physical evidence of Yemen’s ancient civilizations. There is no other explanation for why the Saudi-led offensive should have laid waste to these irreplaceable world archaeological treasures…several sources have confirmed that Unesco and the State Department gave the coalition a list of specific sites to avoid. But far from rebuking its ally for ignoring this advice, the United States is providing logistical, intelligence and moral support for the Saudi air campaign.…This Saudi cultural vandalism is hard to distinguish from the Islamic State’s.”

Will the academic community once again fall in step with the Antiquities Coalition and others demanding a blockade of Yemeni goods, even if it has no positive effect at all?

As the high-pressure campaign continues, it raises another major question:

Will legislators, administration officials, and the academics who have historically backed unnecessary and overbroad import restrictions, including the professors and archaeologists who sit on the Cultural Property Advisory Committee at the State Department, finally take a stand and urge that U.S. policy be based on the facts and on U.S. law?

Hebrew Bible: (Pentateuch: Shemot-Devarim) Yemen: Early Fifteenth Century. David Solomon Sassoon, then Valmadonna Trust Library, MS 7. Sotheby's, December 2015.

Hebrew Bible: (Pentateuch: Shemot-Devarim) Yemen: Early Fifteenth Century. David Solomon Sassoon, then Valmadonna Trust Library, MS 7. Sotheby's, December 2015.