Kim and John Holland have lived in the same Colonial-style brick house in a leafy area of Northwest, Washington, D.C, for over twenty years. The time has finally come for them to start downsizing in advance of retirement. This has been a slow and somewhat painful process of saying goodbye to long held objects associated with beloved friends and family members as well as important parts of their lives.

Young cat on a piano, photo by Lizibou123, 14 August 2014, CCA-SA 40. International license

Kim’s piano is just such an artifact. It is a 1940’s era upright; nothing fancy, but meaningful none the less. Kim has fond memories of her family singing along as her mother played it years ago as some of the only entertainment on a secluded ranch in Montana. After her mother moved to assisted living in Missoula, Kim had the piano shipped across the country to her home in Washington, D.C. Since then, the piano has sat prominently in Kim and John’s living room. Although it doesn’t get played that much, the piano is often festooned with decorations appropriate to the season. When Kim does play, she prefers her cat, Tigger, as her audience. Tigger certainly is appreciative. He sits in rapt attention listening to Kim play old favorites. Her other cat, Puff, is also piano aficionado in his own way. Every so often Kim and John hear Puff “playing” as he walks on the keyboard during one of his nocturnal rounds of the house.

Memories or not, Kim knows that it’s time to part with her piano, but what to do with it? One possible complication is that its white keys, like most from the period, are sheathed in elephant ivory. Kim has wondered if this might be a problem since she got the piano tuned on its arrival to D.C. At that time, the piano tuner indicated that if Kim wanted to replace some of the keys, the replacements would have to be in plastic, not ivory. Kim decided not to spend the money on such a repair but tucked what the piano tuner told her in the back of her mind.

Now that she is considering what to do with her piano, Kim decided to investigate further. As a retired attorney for the federal government, Kim certainly did not want to run afoul of any laws. So, using the research skills she honed over her long career, Kim plumbed the Internet on the subject. Kim already had a notion that that disposing of items containing ivory might be a problem and she was right.

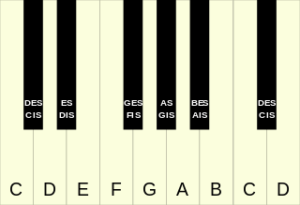

Sounds of the octave written on the piano keys, author Dbc334, Ashaio, 27 February 2016, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

Kim learned that the limits on the sale and transfer of ivory originated with the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), which was designed to ensure that trade in endangered species does not threaten their survival. CITES provides for varying degrees of protection to over 30,000 animal and plant species. It places species into different categories based on the extent to which they are endangered. African and Asian Elephants are listed in Appendix I, which indicates that elephants are considered to be threatened with extinction linked to the international trade in ivory. Under that Convention, the international trade of ivory from African and Asian elephants is generally banned with some very limited exceptions.

CITES is not self-executing and had to be incorporated into a federal law, the Endangered Species Act and its implementing regulations. These federal rules generally ban the U.S. commercial trade in both African and Asian elephant ivory, subject to some exceptions. The major exceptions include what is known as the ESA antique exemption and the de minimis exemption for African elephant ivory. Federal laws do not, however, prohibit donations or gifts of an ivory item, provided that it was acquired lawfully and there is no exchange for other goods or services.

These federal laws only apply to items imported into or exported from the United States or which transit in inter-state commerce. As a result, animal welfare groups have lobbied states and other localities to ban the ivory trade within their jurisdictions. After doing some additional research, Kim located a press release that indicated that a coalition of Washington D.C. based animal protection organizations had successfully lobbied the D.C. Council to ban the sale of ivory within the District of Columbia. That press release certainly made the law sound like the ban was a complete one. However, when Kim read the bill’s actual text, she noted that it contained exemptions for gifts or donations, as well as for sales of antiques over 100 years old and musical instruments produced before 1972 as long as they contain less than 20% ivory by volume.

Paul Cezanne, Juene fille au piano, 1866, Hermitage Museum, public domain.

Not surprisingly, such restrictions have been criticized by antiques dealers and collectors who believe they have been steamrolled by well-organized animal welfare advocacy groups which have relied more on emotion than facts to push their agenda. They complain that draconian restrictions on the trade in antiques will do nothing to protect elephants endangered today but will likely cause the neglect or outright destruction of important artifacts of cultural value. They note that ivory—antique or not—that is confiscated is either burned or pulverized, typically before the cameras so that the authorities can show they are “doing something” to protect endangered elephants.

As draconian as the laws are here, there are even more stringent regulations elsewhere. Recently, the United Kingdom passed the Ivory Act of 2018 which further limits the ability of British citizens to hold even antique ivory. Under that law, there is a total ban in the trade of ivory with very limited exceptions for items made before 1918 of “outstandingly high artistic, cultural or historic value” with valid exemption certificates, and for other limited categories of objects (including pre-1975 musical instruments) that have been registered with the authorities.

In any case, the federal and D.C. laws suited Kim just fine because she planned to gift her piano to her niece anyway. She now just hopes that her niece will be interested. If not, she will have to come up with an alternative, which hopefully will keep her mom’s piano from ending up in a landfill.

Next Month: Will my African Art be repatriated as reparations for the Colonialist past?

Piano-Key butterfly, photo Charles Patrick Ewing, 26 November 2016, CCA 2.o Generic license.

Further Reading:

New Publication: Ivory 2020 Art and Heritage Law, Cultural Property News (July 13, 2020)

Washington, D.C. passes law to ban the sale of ivory & rhino horn, IFAW Press Release (May 5, 2020), (last visited October 13, 2022).

D.C. Law 23-126. Ivory and Horn Trafficking Prohibition Act of 2020, (last visited October 13, 2022).

[1] Peter K. Tompa has written extensively about cultural heritage issues, particularly those of interest to the numismatic trade. Peter contributed to Who Owns the Past?” (K. Fitz Gibbon, ed, Rutgers 2005). He currently serves as executive director of the Global Heritage Alliance. This article is a public resource for general information and opinion about cultural property issues and is not intended to be a source for legal advice. Any factual patterns discussed may or may not be inspired by real people and events.

Piano keys gif, 19 March 2011, author Adwiii, public domain.

Piano keys gif, 19 March 2011, author Adwiii, public domain.