Born from panic and propaganda, the EU’s Regulation 2019/880 was justified by explosive—but unproven—claims that ISIS funded terrorism through a billion-euro antiquities trade. Despite law enforcement investigations, academic reports, and customs operations finding no evidence of such trafficking, the European Commission clung to the myth, empowering a regulatory regime built on fear, not fact. As international agencies, NGOs, and consultants profited from the narrative, the legitimate art trade was left to navigate a punitive system designed to fight a crime that may never have existed.

Beginning in the early 2010’s, alarming claims circulated that ISIS was funding its operations through the looting and sale of antiquities from Iraq and Syria. Widely repeated by media, politicians, and international bodies, this narrative alleged a vast, multimillion or even multibillion euro illicit trade in cultural property.

Passage of EU’s Regulation (EU) 2019/880 and the European Commission’s subsequent refusal to modify it were widely justified as a response to this alleged ISIS-directed looting. At hearings, EU Parliament members cited fears that sales of illicit antiquities could fuel further global attacks.

False claims about terrorists looting art to order for Western collectors were widely publicized in campaigns by the Antiquities Coalition, including by its 2016 #CultureUnderThreat Task Force, which summarily declared a causal effect between the “multi-billion-dollar demand for art and antiquities” and the looting and destruction of archaeological sites. Antiquities Coalition founder Deborah Lehr had laid the grounds for these evidence-free tales by repeated public announcements associating illicit trade with political unrest, telling an audience at the Middle East Institute in 2014 that there was a “very conservative estimate” of $3 billion looted in Egypt since the revolution in 2011, based on satellite imagery and sales on the local markets, and stating that, “With Egypt, it is probably 3-10 billion, globally it has to be a much more significant number” and “Coming out of Syria, it is $2 billion” (Deborah Lehr 2014).

However, concrete evidence for these claims was never produced. Reputable investigations, such as the 2016 report by the Dutch National Police’s War Crimes Unit, found no meaningful data to support the idea that ISIS profited significantly from antiquities trafficking. Customs and law enforcement agencies in Europe and the U.S. reported no increases in seizures or arrests connected to Middle Eastern antiquities.

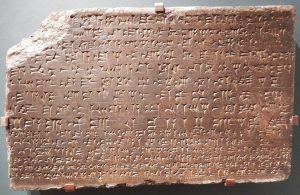

Fragment of a stone relief in the Northwest Palace, carved with the ‘standard inscription’ that records the king’s names, titles and ancestry in Assyrian. This part relates to Ashpurnasirpal’s conquest of lands from Uratu to the mountains of Lebanon. ANLOAN109.1 By BabelStone (Own work) CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

In the United States, all imports of Iraqi cultural goods had been banned since 2004 under the Emergency Protection for Iraqi Cultural Antiquities Act. This law banned importation of items as minor as postage stamps and personal records – yet it appeared to do little to prevent the destruction of cultural heritage during conflict. The individuals caught with Iraqi artifacts have for the most part been journalists, contractors, or soldiers, not dealers or collectors.

To test the assumptions of widespread trafficking of ISIS-looted objects entering Europe, the first Operation Pandora, a joint operation among 18 countries, was launched in 2017. After 40,000 checks, no Middle Eastern war zone artifacts were identified in the EU market. Similarly, the World Customs Organization’s 2016 Illicit Trade Report documented no seizures in Western Europe (except in Switzerland) of looted Middle Eastern antiquities.

The RAND Corporation’s thorough analysis in 2018 documented the lack of verifiable instances where antiquities sales directly funded terror – and found few being trafficked online – and identified anti-trade activists and law enforcement as responsible for circulating a false narrative (RAND 2018). On their part, European and American art dealer representatives made stringent efforts to self-police galleries and art fairs for possible ISIS-linked items, reporting suspicious activities to police and making it clear that these illicit antiquities were not welcome in Western markets.

Despite this, EU officials—including Commissioner Pierre Moscovici—continued to cite long-debunked figures (such as a €2.5–5 billion annual trade) including in the July 2017 Fact Sheet they published to justify sweeping new legislation. These claims were even refuted by the Commission’s own Deloitte report, which failed to find evidence that the European art market funded terrorism.

Facing mounting pressure and poorly substantiated regulatory initiatives, major art market stakeholders—including the Confédération Internationale des Négociants en Oeuvres d’Art (CINOA), the International Association of Dealers in Ancient Art (IADAA), and national dealer associations—organized to contest the proposed measures. Between 2017 and 2019, they submitted independently verified data, met with officials, and wrote to UNESCO’s Director-General Irina Bokova, calling for transparency and asking her to distinguish between the legal trade and criminal actors.

They emphasized that the EU already banned imports of cultural goods from Iraq and Syria, rendering additional legislation redundant. Moreover, the new rules—particularly Regulation (EU) 2019/880—would delay trade, damage small businesses, and impose significant burdens on legitimate art market participants.

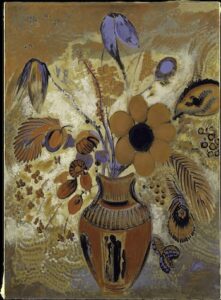

Odilon Redon (French 1840–1916) Etruscan Vase with Flowers, 1900–10. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Maria DeWitt Jesup Fund, 1951.

Despite these clear flaws, Regulation 2019/880 was approved in April 2019. The Commission’s own Ecorys report on the illicit trade had been completed, but its publication was delayed until after the legislation had passed, perhaps because it showed no real evidence!

In March 2021, the Commission released the Draft Implementing Regulations for 2019/880. These 45 pages of procedures and documentation requirements were described by market groups as “unnecessarily complicated, burdensome, and disproportionate.” Critics emphasized the regulations would obstruct art fairs, chill international lending to EU museums, and pose legal risks due to vague and unworkable standards.

After a short four-week comment period, objections were submitted by dozens of organizations and individual members of the art trade, including the International Association of Dealers in Ancient Art (IADAA), Antiquities Dealers’ Association (ADA), SNA, IAPN, ACCG, and CINOA. Still, the final regulations advanced with little substantive change, and the European Commission continued to treat the link between terrorism and the art market as settled fact, despite the lack of evidence.

In June 2023, the European Commission announced the creation of a dialogue framework with the art trade under the umbrella of the Cultural Heritage Forum, coordinated by the Directorate General for Education, Sports, Youth and Culture (DG EAC). A new sub-group was established specifically to address issues related to the protection and trade of cultural goods within the EU single market.

While this appeared to be a long-overdue opportunity for cooperation, the art trade’s participation did not result in meaningful change. There were only three meetings and given the structure of the DG EAC, most trade and tax issues fell under the purview of other Directorates General, limiting opportunities for direct influence. Despite the presentation of evidence-based concerns and suggestions for improvement, the Commission was willing to make only minor changes to either the regulation or its implementation process, where it still had leeway to do so, such as raising the threshold for inclusion of objects. The working group, while a formal mechanism for communication, has had little demonstrable impact on policy outcomes so far. Stakeholders described the exercise as symbolic rather than substantive, reinforcing concerns that policy decisions were being driven by politics, not facts. Time will tell whether damage to EU economies and cultural institutions will eventually propel the European Commission to make needed regulatory changes.

A Policy Built on Myths and Money

As of 2025, the European cultural goods regulatory framework remains fundamentally shaped by unsubstantiated claims of antiquities trafficking linked to terrorism and money laundering. (It’s worth noting that as the lack of any connection to terrorism became obvious, accusations of money-laundering got louder. These claims were only anecdotal and easily disproved, as art businesses use banks like other businesses.)

Regrettably, despite the trade’s calls for a rational, evidence-based approach, the EU’s regulatory apparatus has cemented a punitive regime that fails to differentiate between the legitimate trade and the very criminals it purports to target.

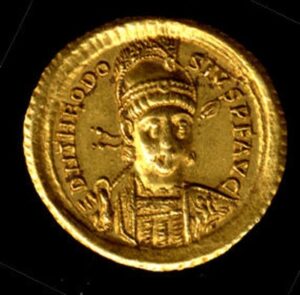

The coins of early Byzantine emperors conveyed imperial ideals through inscriptions and images. They were used in international trade, to pay soldiers and taxes. CCA-SA international license.

The art and antiquities trade has repeatedly offered cooperation, transparency, and proactive measures to protect heritage. Yet UNESCO, the European Commission, and other bodies have largely refused meaningful dialogue, preferring to legislate based on speculative threats rather than demonstrable realities.

It is noteworthy that the reported multi-billion-dollar illegal trafficking has also generated an industry of sleuths, from amateurs to actual police, who have built careers around hunting for illicit antiquities. These activities have so far provided little evidence to show that there is a current market for looted antiquities. Facebook and other Internet venues have featured essentially worthless items – the decades-old detritus of the bazaars and hundreds and hundreds of fakes. U.S. police, notably Manhattan Assistant District Attorney Matthew Bogdanos’ Antiquities Trafficking Unit, have been left making cases against museum and collectors who have possessed the objects for decades – even for 70 years! Italy’s Carabinieri have ended up arresting domestic Italian tombaleros and pressuring the return of long-held objects from U.S. and European museums and collectors. Nonetheless, spicy rumors of a Dark Internet marketplace and antiquities crypto-businesses continue to circulate without any evidence.

What is often forgotten is that the industry “experts” who contributed to the EU Commission process also have a financial interest in promoting a terrorist or organized crime narrative. The Financial Action Task Force (FATF), the global money laundering and terrorist financing watchdog, continues to argue that antiques are used for laundering money funding terrorism. Despite the fact that antiquities are not only the smallest (less than 1%) but also the weakest art market sector, and that ISIS’s real funding came from looting minerals and oil, not antiquities, FATF’s updated risk frameworks and AML mandates influenced EU regulation. FATF’s guidance (2023) on “Art and antiquities” markets as risk sectors continue to benefit its own regulatory mission and expansions.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) reports often lack specific case documentation, but as advocacy tools, they ensure continued funding and institutional relevance. Wildly inaccurate estimates of the annual profits from illicit trade (in each case ranging between a few hundred million and three to six billion dollars– not much of an “estimate”!) on page 8 of UNODC’s 2016 report are frequently referred to as UNODC figures, when they are not, and used to justify further restrictions.

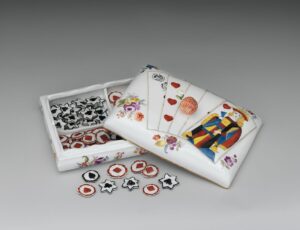

Box with eighty-one game counters, ca. 1760, Hard-paste porcelain, Meissen Manufactory (German, 1710–present). For the Ace of Spades, the painter used an original card bearing the Saxon tax stamp that was imposed on all imported playing cards.

UNODC hosts EU grant-funded workshops and increased regulation reinforces its authority. The Association for Research into Crimes against Art (ARCA) presented at EU hearings and issued “risk indicators.” ARCA receives EU funding for training and consultancies focused on anti-trafficking frameworks—so stricter laws directly sustain its revenue stream. Many of these bodies are funded to train enforcement authorities, creating potential mission-based incentives to amplify the “terror” threat. The Antiquities Coalition, a U.S. nonprofit with ties to Middle Eastern governments, has campaigned vigorously against so-called “blood antiquities,” and has received over $1.3 million in U.S. government grants.

Scholarly sources caution that trafficking claims often rely on high-profile incidents rather than systematic data. Without pointing the finger at any of these entities for deliberately promoting a false narrative, it should be clear that they have a financial stake in encouraging burdensome regulation and heavy-handed enforcement through a variety of government entities – while the art trade is on its own in working to ensure a transparent, lawful circulation of antiquities.

A March 2025 survey of a dozen leading bodies from law enforcement (FBI, Homeland Security, Interpol, Europol, World Customs Organization, FATF) to NGOs (UNESCO) and governments (European Commission, US State Department) found that none was able to supply independently verifiable data on looting and trafficking of cultural property. The WCO went as far to state that the figures did “not exist.”

CONCLUSION

The concerns surrounding Regulation (EU) 2019/880 are well-founded and supported by extensive expert commentary. The regulation imposes a high-stakes compliance regime, placing the burden of proof squarely on the importer. National authorities—particularly in France—are bracing for market disruption, while the Netherlands appears committed to strict enforcement, raising fears of trade displacement from major European art markets such as Maastricht.

In essence, the new regime will likely have a chilling effect on legitimate trade in ancient and ethnographic art. Many objects cannot be documented to the required standard, and the risk of criminal liability for these unknowns is likely to deter cautious collectors and dealers. Rather than achieving transparency, the regulation may instead push trade toward less regulated markets outside the EU.

In this new landscape, importers will face complex and burdensome compliance requirements, legal uncertainties, and fragmented enforcement. The result is a policy environment that damages the cultural sector, burdens governments, and does little to protect heritage from actual destruction or looting in conflict zones.

SELECTED SOURCES

James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903), Taxes! (from Sketchbook 1854–55), Black ink and graphite, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY.

Antiquities Coalition, #CultureUnderThreat: Recommendations for the U.S. Government, 6 (Apr. 2016)

Antiquities Dealers Association, Unesco Marks 50th Anniversary Of 1970 Cultural Heritage Convention With Fake Campaign (Dec 2021)

Antiquities Dealers Association, None of the world’s top authorities able to supply accurate global data on cultural goods trafficking (Mar 31, 2025)

Anna Brady, About to throw a wrench in the market: a legal expert’s view on upcoming changes to EU import law, The Art Newspaper (3 June 2025).

Anna M. de Jong, The Cultural Goods Import Regime of Regulation (EU) 2019/880: Four Potential Pitfalls, Santander Art and Culture Law Review 2/2021 (7): 31-50.

Kate Fitz Gibbon, Katherine Brennan, Bearing False Witness: The Media, ISIS and Antiquities, Art and Heritage Law Report, Committee for Cultural Policy (December 2017)

Kate Fitz Gibbon, RAND Corp Report Demolishes Assumptions on Antiquities and Terror, Cultural Property News (July 30 2020)

Deborah Lehr, Middle East Institute, Stolen Heritage: Cultural Racketeering in Egypt, YouTube (April 24, 2014) https://youtu.be/h4BaIXjMWnw.

Ivan Maquisten, No EU problem with terrorist antiquities, so let’s legislate for it, Cultural Property News, (Sep 21 2017)

Matthew Sargent, James V. Marrone, Alexandra Evans, Bilyana Lilly, Erik Nemeth, Stephen Dalzel, Tracking and Disrupting the Illicit Antiquities Trade with Open-Source Data, RAND Corporation, (2020).

Tom Seymour, The EU law that’s threatening to up-end the antiquities market,

Financial Times Ben Taub, The Real Value of the ISIS Antiquities Trade, The New Yorker, (Dec 4 2015)

Pierre Valentin, EU Regulation 2019/880 on the importation of cultural goods – The EU Commission Q&A (Part 2) Fieldfisher (June 3 2025).

Pierre Valentin, EU Regulation 2019/880 on the importation of cultural goods – The EU Commission Q&A (Part 1) Fieldfisher (April 4 2025).

Alexandre François Desportes, Still Life with Silver, French, 1720s, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY. Desportes worked for Louis XIV and Louis XV of France, in the tradition’s most opulent vein. It replicates the ostentatious display of actual dining room buffets of fruits together with sculptures, silver metalwork, and other objects that attested to their owner’s buying power and global reach, including Japanese Kakiemon and Imari porcelain bowls. Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY.

Alexandre François Desportes, Still Life with Silver, French, 1720s, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY. Desportes worked for Louis XIV and Louis XV of France, in the tradition’s most opulent vein. It replicates the ostentatious display of actual dining room buffets of fruits together with sculptures, silver metalwork, and other objects that attested to their owner’s buying power and global reach, including Japanese Kakiemon and Imari porcelain bowls. Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY.