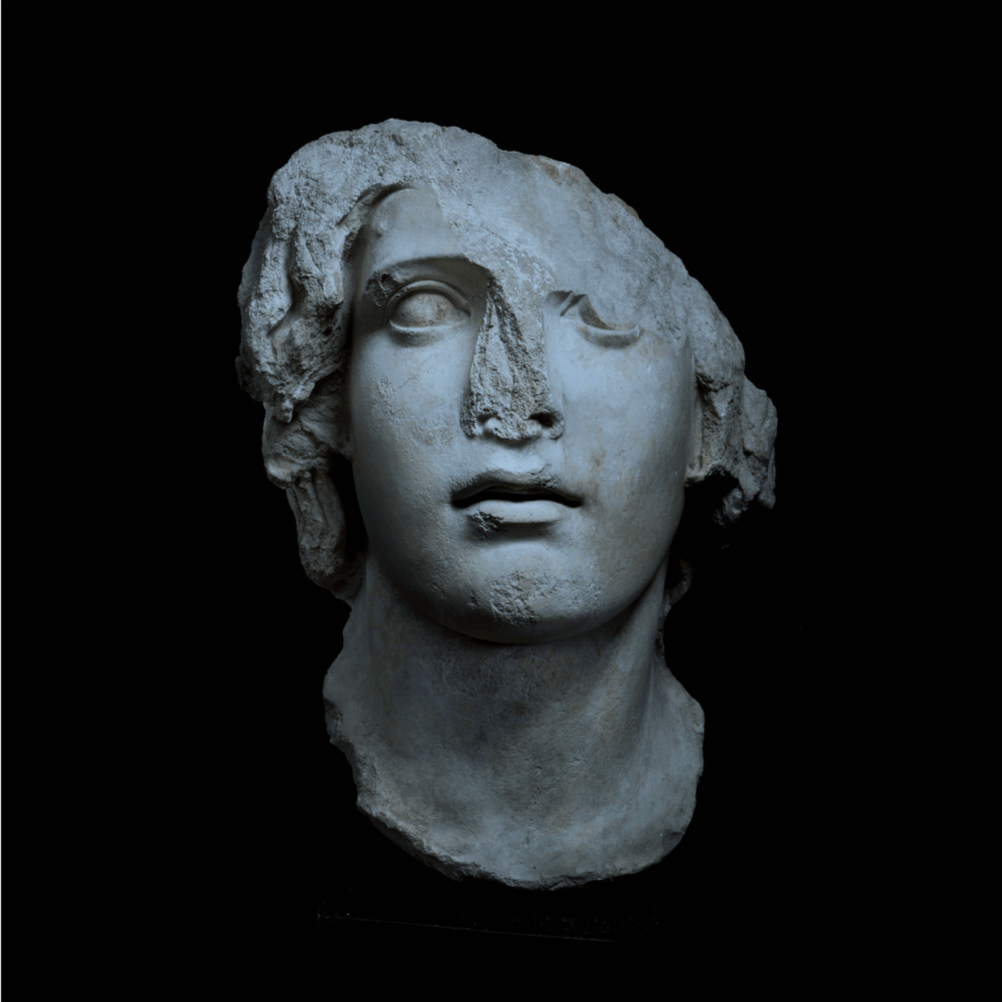

The Safani Gallery, one of the oldest antiquities galleries in New York, has filed a lawsuit against the Italian Republic in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York. The Safani Gallery purchased a statue dating to about 300 BCE, known as the Head of Alexander from a Foundation through a London-based dealer, Classical Galleries Ltd., in June 2017. The Safani Gallery paid $152,625 for the statue, which was previously in the world-renowned collection of Hagop Kevorkian, and was known to have circulated in the international market for many decades afterwards, and to have been sold at public auction. The Complaint filed by the gallery notes that it was given express representations and warranties of the authenticity, ownership, export licensing, and other attributes of the provenance from the Foundation that sold it. The Safani Gallery states that it followed all U.K and U.S. laws regarding the import of the statue into New York.

The gallery claims that it is the sole and legal owner of the statue. It is seeking a declaratory judgment from the court that the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office wrongfully seized the marble bust from the gallery. (The Manhattan DA was acting as agent of the Italian Republic in the seizure action.) The gallery’s lawsuit states that the head was improperly seized and that there is no actual evidence that it had ever been stolen or unlawfully exported.

The gallery’s Complaint, filed on November 12, 2019, seeks the immediate return of the marble bust and damages for losses caused as a result of Italy’s wrongful action.

The lawsuit details the history of legitimate, public sales of the statue before it was purchased by the gallery. It notes that despite the statue being publicly sold and published several times, Italy made no complaint and never challenged a prior sale.

Research performed by the Art Loss Registry showed that the bust had been in the Kevorkian Collection, most likely dating prior to WWII. Auction records also show that on multiple occasions since 1958, the Head of Alexander appeared in illustrated catalogs and was on public display at auction houses. A Sotheby’s 2011 auction listing also attests to both Kevorkian’s ownership and date when he is thought to have acquired it.

Italy has argued that the Head of Alexander was likely taken from the Forense Museum (Antiquarum Forense) in Rome but has not presented evidence that it was ever in any museum or museum inventory.

The Manhattan DA’s office asserted in court filings in 2018 that the lack of a paper trail or an export permit authorizing the statue’s removal from Italy from 50-100 years before marks it as a typical clandestine export in violation of Italy’s national patrimony law. The Safani Gallery countered in its Complaint that the Head was not the type of object covered by Italian patrimony law at that time. It further states that Italy has no evidence that it required or issued export licenses for similar objects, and that Italy has not retained any record of any export license from the time period.

The Safani Gallery makes the point that export without an export license does not by itself turn an object into stolen property or lead to a legal conclusion that it is stolen property.

The gallery’s Complaint notes that the Italian Republic’s claim that the head was stolen is based on its assertion that (1) the bust was excavated after 1909 and was and remains Italian property because of a national patrimony law, and (2) that Italy can find no record of an export license authorizing its removal from Italy. But the Complaint notes that there is no evidence to establish that the Head is covered by Italy’s patrimony laws, and points out that Italy itself informed the Manhattan DA that the Head was likely excavated around 1899.

On November 13, Justice Thomas Farber of the New York State Supreme Court denied a ‘turnover’ request for the marble head of Alexander seized by the Manhattan District Attorney’s office in 2018. The Manhattan District Attorney’s office sought to turn the bust of Alexander over to Italy based on there being no documentation from the 1970s and earlier; the gallery argues that an object cannot reasonably be deemed stolen when there is no evidence that it is stolen, simply because there are no records from 50 or more years before.

Cultural Property News will follow this developing story.

Related stories:

Head of Alexander the Great as Helios, God of the Sun, c. 300 BCE, courtesy Safani Gallery, Inc.

Head of Alexander the Great as Helios, God of the Sun, c. 300 BCE, courtesy Safani Gallery, Inc.