This article is drawn in part from a lengthy analysis of U.S. cultural property policies, laws, and enforcement prepared by the Committee for Cultural Policy for a nine-country project initiated by CCP and administered by TrustLaw, a program of the Thomson Reuters Foundation. In an earlier article, Cultural Property News discussed the 1983 Convention on Cultural Property Implementation Act (CPIA).

The United States has two independent and at times conflicting international cultural property legal regimes. One is the 1983 Convention on Cultural Property Implementation Act (CPIA). (See CPAC – Building a Wall Against Art, Cultural Property News, June 28, 2018.) The second U.S. legal regime governing ownership and the trade in cultural property operates under a theft statute, the 1934 National Stolen Property Act, which was intended to prosecute transportation of stolen objects, such as cars, across state lines.[i] It is a criminal violation of the National Stolen Property Act to knowingly possess, conceal, sell, or dispose of any goods of the value of $5,000 or more, which have crossed a State or U.S. boundary after being “stolen.”[ii] This general theft law, not the Cultural Property Implementation Act, is now the primary legal foundation in the U.S. for foreign ownership claims for antiquities and other cultural property.

The National Stolen Property Act (NSPA) covers all forms of tangible property, including cultural property, both foreign and domestic, simply as a form of “property.” (Civil forfeiture, under which property may be seized as “stolen” without having to prove the criminal elements of a National Stolen Property Act violation, is also commonly used in cultural property cases.)

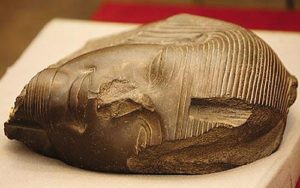

Fragment of a wall frieze from Persepolis, owned for fifty years by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, sold to its insurer, and later seized from a dealer in New York, then returned to Iran in 2018.

The Meaning of “Stolen”

It is important to note that anything “stolen” in the traditional sense of the word – taken unlawfully from a person or institution – will always be treated as stolen in the U.S., and such items would be returned to their owners under both state and federal laws. However, an object considered “stolen” under a foreign national ownership law does not have to be actually taken from a person or an institution that possesses it.

When objects in a museum collection are described as “stolen” in the press or by cultural property activists, they are often not using the word in its ordinary sense. Instead, the term “stolen” is used in the context of:

- taken out of a foreign country without explicit permission from its current government,

- taken out of a foreign country with permission, but at a time when the country was subject to a colonial government, or when the foreign government was in a weak position relative to Western powers, to

- taken out of a foreign country with a national ownership law, whether the law was enforced or not.

Much of the debate surrounding the enforcement of foreign governments’ claims under the NSPA involve cases where the meaning of “stolen” under a national ownership law does not match what is considered “stolen” in the ordinary sense of the word.

Often, foreign ownership laws are not compatible with U.S. concepts of private property rights; the foreign laws may “nationalize” private property. Some find it troublesome that the U.S. is enforcing foreign laws against U.S. citizens that would not meet constitutional standards under U.S. law.

Foreign national patrimony laws may treat unknown objects, that is, objects still under the ground, objects sold by their legal owners without permission of the government, or objects in private ownership whose owners have not registered them timely with the foreign government as automatically “stolen.” These foreign laws, which vest ownership of all cultural property in the state, can also make objects “stolen” under U.S. law if they are exported without permission.

Head of Amenhotep on its return to Egypt, Schultz case. Daily Telegraph, Photo: Jane Mingay

By whatever means an object is defined as “stolen” under U.S. law, there are serious consequences to that designation. No thief can pass good title to that “stolen” object. A “stolen” object retains its stolen status forever, no matter how long ago the “theft” occurred or how many owners’ hands the object passed through. Its “stolen” status does not change if it is purchased in good faith without knowledge of the original theft.

McClain and Schultz

The National Stolen Property Act first became a key element of U.S. cultural policy when the court in the 1979 McClain case[iii] found a foreign national patrimony law to be enforceable in the U.S. if it met certain criteria. An object could be considered “stolen” in the U.S. if the country of origin could show that the object was discovered within its territory, that a patrimony law that vested ownership of all such objects in the State was in effect when the object was removed from that country, and that the foreign patrimony law was not so vague as to violate the due process requirements of the U.S. Constitution.

Today, as a result of McClain and the Schultz case[iv] that followed it decades later, foreign nationalizing laws, if held valid by a U.S. court, can determine the ownership of foreign cultural property in the U.S. Foreign countries often protect cultural property through both export controls and national patrimony laws. The U.S. does not enforce foreign export control laws, but under the McClain doctrine, it does recognize national patrimony laws as creating an ownership interest held by the foreign state.

Under the McClain doctrine, an object sold by a private owner in a foreign country, but exported without permission of the foreign government may be considered “stolen” under the foreign government’s national ownership law. The allegedly stolen property in the US may be seized, and if deemed stolen, the object is forfeit to the US government.

Conflict with the CPIA

Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, architect of the 1983 Cultural Property Implementation Act, critic of its operation, and author of legislation to eliminate its conflict with the N.S.P.A., U.S. Congress photo

The congressional sponsors of the Cultural Property Implementation Act understood that there was a conflict between the CPIA’s selective import restrictions and foreign nations’ blanket assertions of ownership of all cultural property. It was clear that an importer, art collector or museum could be in compliance with the CPIA, and at the same time be in violation of the NSPA, a federal criminal law with harsh penalties.

The ability to use a foreign nationalizing statute rather than the congressionally–mandated legal regime under the 1983 Cultural Property Implementation Act (CPIA) has made prosecutions of dealers or collectors of art easier and effectively eliminated the protections in the CPIA granting repose both to art long in the United States, and to art which enters the U.S. after a lengthy stay in a third country.

The congressional architects of the CPIA, Senators Patrick Moynihan and Bob Dole, sought to ensure that the CPIA, which was intended to stop current looting and which reserved independent judgment to the U.S. on the scope of its import controls, rather than allowing a foreign country to unilaterally define what cultural property could legally enter the U.S., was not made moot through use of the National Stolen Property Act. A different Congressional committee had jurisdiction over the National Stolen Property Act, however, so separate legislation was needed to make the carve-out.

The senators introduced a companion bill, S. 2963 in 1982, and again in the form of S. 605 in 1985, soon after passage of the CPIA, to amend the National Stolen Property Act so that the NSPA would not “apply to any… archaeological or ethnological materials taken from a foreign country where the claim of ownership is based only upon… a declaration by the foreign country of national ownership of the material…”[v]

However, the State and Justice Departments opposed S. 2963 and S. 605, based upon their desire to retain the ability to use the NSPA in a limited number of “egregious” cases. Without their support, both bills failed to pass. without any limitations on the scope of the NSPA, the NSPA and its related doctrine of civil forfeiture became the defining cultural property law of the U.S. (Recent attempts to amend the NSPA would have vastly expanded the scope of the NSPA. These include the failed U.S. Terrorism Art and Antiquity Revenue Prevention Act of 2016, or TAAR Act, which, among other things, proposed reducing the threshold of $5,000 value in the NSPA to $50 for cultural property.)

Senator Bob Dole, who worked with Moynihan to reform the N.S.P.A.

As William Pearlstein states in White Paper: A Proposal to Reform U.S. Law and Policy: [vi]

“The disjunction between the two statutes is nowhere more apparent than on this practical, mechanical level. McClain throws into confusion the validity of the import certification process established under the Implementation Act, a feature that is critical to the integrity of the CPIA. An importer of Designated Materials who takes the trouble to comply with the “satisfactory evidence” safe harbor under Section 307 or the “published/old collection” safe harbor under Section 312(2) should be dismayed to learn that McClain makes such compliance irrelevant.”

U.S. courts have examined foreign national patrimony statutes in several cases, coming to somewhat different conclusions but essentially laying out criteria that may determine whether a specific national patrimony statute is valid. Key cases include United States v. McClain, Peru v. Johnson,[vii] and United States v. Schultz. However, whether a foreign statute will qualify as an ownership law for the purpose of a prosecution under the NSPA is not decided until a case comes to trial. However, only a handful of source country laws have been examined in the courts. The uncertainty and expense of a defense leaves U.S. collectors and collecting institutions unwilling to risk opposing a foreign claim. This lack of legal certainty chills individual and museums’ willingness to participate in the global art trade, even when buying from overseas, and even from other museums.[viii]

State and County Level Cases Involving the National Stolen Property Act

Colonel Matthew Bogdanos, USMC, conducts a Pentagon press briefing on Sept. 10, 2003. Author Helene C. Stikkel, U.S. Marine Corps photo.

In addition, U.S. federal and even county-level authorities have implemented ad hoc anti-antiquities trade policies in which civil forfeiture is used to seize objects that are assumed to be “stolen” without proof of the circumstances. U.S. courts have been willing to accept a foreign nation’s patrimony law to define an object as“stolen” under US law. Authorities have utilized state laws not specifically designed for cultural property matters by adopting the terms of foreign patrimony laws that deem objects as stolen from ownership by the foreign state.

In New York City, the art capital of the United States, an Assistant District Attorney for the County of New York, Matthew Bogdanos, has recently raised the stakes for collectors, auction houses, and art dealers with seizures of antiquities that were not recently looted, but have been in private collections for many decades. (See New York District Attorney Goes After Art Collections, Cultural Property News, Feb. 11, 2018) A string of seizures using a state law regulating pawnbrokers have resulted in agreements to forfeit very valuable antiquities. The New York District Attorney’s office relies on the same national patrimony laws that are litigated in NSPA cases to establish that the cultural property seized under the NY pawnbroker’s law is actually stolen. Since a court would not determine the validity of a foreign state’s ownership claims until well along in a court case, both the costs of defending against such charges and the potential damage to an owner’s reputation are high. Under these circumstances, civil forfeiture has become “a third theory of liability.”[ix]

A number of legal scholars have criticized the McClain/Schultz doctrine as poor public policy, arguing that objects covered by a foreign patrimony law are not really owned by the nation and that recognition of such ownership rights greatly decreases the availability of objects for both private collectors and museums in the United States. Proponents of McClain/Schultz doctrine argue that patrimony laws are an effective means of reducing incentives to purchase undocumented antiquities because they deny title to the finder. Given that the vast majority of antiquities are undocumented, this argument can amount to a general assertion that the market in antiquities should not exist.

Criminal Possession or Transportation related to NSPA

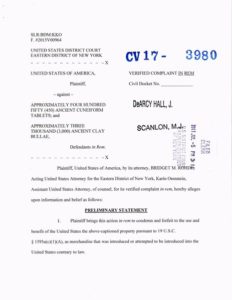

United States government civil complaint from a smuggling case involving Approximately Four Hundred Fifty (450) Ancient Cuneiform Tablets and Approximately Three Thousand (3000) Ancient Clay Bulae, the Hobby Lobby case.

In order to be charged with criminal possession under the National Stolen Property Act, an individual must know that the cultural property in his or her possession was “stolen” in the traditional sense, or removed from a foreign country without permission after enactment of a national patrimony law. In many cultural property cases, there is not sufficient evidence of knowledge to proceed criminally. Stolen property can be forfeited in these cases administratively or through a civil in rem action. Civil forfeiture, however, enables law enforcement to seize art without proving the elements required to obtain a criminal conviction.

To obtain a seizure warrant, a law enforcement agent writes an affidavit explaining the facts of a case to the judge (i.e., probable cause to believe the cultural property in question is stolen). Once the agent obtains a seizure warrant, he or she may seize the stolen property. If prosecuting a defendant, the Assistant U.S. Attorney can use criminal forfeiture to establish title in the U.S. government. Once convicted, one of the penalties is forfeiture of the item to the U.S. government.

[i] 18 U.S.C. §§ 2314–2315.

[ii] The full text is [w]hoever transports, transmits, or transfers in interstate or foreign commerce any goods, wares, merchandise, securities or money, of the value of $5,000 or more, knowing the same to have been stolen, converted or taken by fraud.” 18 U.S.C. § 2314.

[iii] United States v. McClain, 551 F.2d 52 (5th Cir. 1977), 545 F.2d 998 (5th Cir. 1977), 593 F.2d 658 (5th Cir. 1970, cert. denied, 44 U.S. 918 (1979).

[iv] United States v. Schultz, 333 F.3d 393 (2d Cir. 2003), cert. denied, 540 U.S. 1106 (2004).

[v] S. 2963, 97th Con. (1982); S. 605, 99th Cong. (1985).

[vi] Pearlstein continues, “Even if one assumes that U.S. Enforcement Agencies would not apply McClain against Designated Materials imported in compliance with Section 307, it is clear that McClain continues to apply to non-Designated Materials from the same State Party. This leads to the absurd result that the criminal penalties for importing non-Designated Materials are worse than the civil penalties to which Designated Materials are subject. William G. Pearlstein, White Paper: A Proposal to Reform U.S. Law and Policy, 32 Cardozo Arts & Ent. L. J. 561, 594 (2014). https://www.culturalheritagelaw.org/resources/Pictures/Pealstein.White%20Paper.pdf

[vii] 720 F.Supp. 810 (C. D. Cal. 1989).

[viii] Kate Fitz Gibbon, No More Good Provenance, Cultural Property News, Mar. 29, 2013, https://culturalpropertynews.org/no-more-good-provenance/.

[ix] William Pearlstein, Symposium, Reform of U.S. Cultural Property Policy: Accountability, Transparency, and Legal Certainty, April 10, 2014, https://culturalpropertynews.org/reform-of-u-s-cultural-property-policy-accountability-transparency-and-legal-certainty/

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officers recently recovered three stolen vehicles in Baltimore that were being shipped to Africa, including two premium 2017 models. CBP officers at the Port of Baltimore routinely examine outbound vehicles and export documentation and occasionally encounters vehicles that are reported stolen. Photo provided by: U.S. Customs and Border Protection

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officers recently recovered three stolen vehicles in Baltimore that were being shipped to Africa, including two premium 2017 models. CBP officers at the Port of Baltimore routinely examine outbound vehicles and export documentation and occasionally encounters vehicles that are reported stolen. Photo provided by: U.S. Customs and Border Protection