The cultural heritage world is well aware that infrastructure development, from dams to metro building, can lead to both archeological discoveries and the loss or destruction of cultural resources. The demolition of a building in Mexico City may reveal a new temple to the Aztec wind god Ehécatl; an Incan pyramid is destroyed to make way for a new building in Lima, Peru.

Climate change both reveals and destroys the archaeological record. At the same time that water levels are rising in Venice, submerging sidewalks and threatening the city’s structural integrity, artifacts uncovered by glacial melt around the world have created a new field, Glacier Archaeology.

In February 2018, CPN described Scotland’s impressive response to climate change in developing systems to assess preservation measures for cultural sites at risk. Over the next few months CPN will explore other aspects of the effect of climate change on cultural heritage.

Climatologists are now projecting that ocean levels will rise by as much as six feet by 2100. This will result in increasingly higher tides and coastal flooding around the world. The rising water will inundate many low lying island nations in the Indian and Pacific oceans. At their highest point, the Maldives are a little less than 8 feet above sea level; the average elevation of the atolls and island of Kiribati is just around 6.5 feet. The elevation of Tuvalu and the Marshall Islands is about the same. Facing the possibility that a significant portion of their land mass will soon be submerged, these island nations are assessing their options. Some are considering moving whole populations to higher ground on other islands or in other nations. Others are looking to technology and help from the international community to increase their height and landmass by building man-made islands.

‘Climate-induced migration’ and ‘climate refugees’ are terms that have developed to describe what will happen to populations that will need to leave their homelands due to raising ocean levels, desertification, crop failure, drought, glacier melt, soil salination and other effects of a changing climate. There is much debate over climate change – whether it is happening, whether it is man-made, whether specific natural events are related to it – but no one can deny that ocean levels are rising.

The loss of land, homes, and livelihood that migration brings is devastating enough. But there is also the deeper loss of the connection to the land and to the historical and cultural sites significant to the people of these threatened regions. Humanitarian aid organizations note that in refugee populations, retaining cultural identity is important to community well-being. The rituals, stories, dances, songs and culturally significant portable objects specific to a group of people help to keep a culture together and provide familiar meaning to life in a new context. But what can’t easily migrate with a population is the land and what grows on it – the homes and familiar foods grown and shared between neighbors, or the burial sites and shrines that are deeply intertwined with personal and community identity.

The Republic of Kiribati, a Case Study

The Republic of Kiribati (formerly the Gilbert Islands) has been inhabited for over 3,000 years. Like many island nations in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, Kiribati exists as a series of coral atolls – 33 in this case. The islands straddle the equator north of Fiji, spreading across 1.3 million square miles of ocean. Kiribati is an example of one government leader’s attempt to meet the challenge of inevitable environmental change with a safety-net providing for organized migration. It also shows how a backlash against such innovative strategies, funded by global economic powerhouses, can result in complete denial of the consequences of environmental change and a focus on short term development instead.

The Kiribati people are deeply connected to the sea, the land and to the spirits that they believe reside there. The Te Kamaraia and Nei Temakua shrines, which are composed of sacred stones and shells, are just two of many shrines to these spirits that have been utilized for generations. Both are under threat from rising seas. The people wonder what will happen to the spirits and in turn their connection to the spirit world when the land is submerged.

Maneaba in Babaroroa, North of Arorae island, Kiribati. Author: Rafael Ávila Coya, 20 August 2010, Wikimedia Commons.

Central to Kiribati life is the Maneaba, the meetinghouse that is the heart of the community. In their origin story the Kiribati tell that the Great Spirit Nareau originally created the Maneaba for his people.

“Before anything else existed, there was Nareau. He was awakened from eternal sleep by a voice calling to him as a breeze against the warm night, “Nareau. Nareau. Nareau arise. There is much work to be done.” As he awoke from his sleep, he realized that the voice was his own and that the visions he had experienced were not his dreams but a foretelling of the world he would create. A sealed sphere emerged from the darkness, which Nareau realized he must open. He stomped on it in an effort to break the form open, but only managed a small crack. This was enough to see that inside were various creatures including the octopus, shark, turtle, and eel. He also saw the flattened bodies of humans. He enlisted the help of the creatures to pry open the shell from within. He instructed the octopus to donate two arms as sustenance for the eel who was to force the sphere apart to his furthest reaches. As the eel lifted, the octopus stepped upon his tail causing the eel to leap into the heavens, and can now be seen in the night sky as the Milky Way. The creatures succeeded in breaking apart the sphere. This enabled Nareau to breath life into the flattened people, thus becoming the People of Creation. Nareau then surveyed the limitless waters as they merged with the infinite sky and was disturbed by the loneliness. He gathered his people beneath the maneaba structure and told them “This land and the vast expanse will become a world of fellowship amongst men.””

– Arthur Chen, “Cultural Heritage of Kiribati Field Study,” Center for World Heritage Studies.

Building a Maneaba is a community endeavor and each part of the structure has a symbolic meaning and particular function. The orientation of the Maneaba is related to the direction of the sea, with the entrance to that side. The organizational structure within the Maneaba is the basis of community and national governance.

Central Intelligence Agency, USA, map of Pacific Ocean islands near the equator.

Already, Kiribati communities have experienced the effects of rising seas. Buildings that stood on dry land a few decades before are now inundated with water during high tides. Changes in rainfall and soil salination from rising sea levels are affecting areas where traditional foods such as breadfruit and taro are grown. The loss of viability for plant life impacts individual livelihoods and redirects the islanders toward increased dependence on different, imported foods.

In 2014, President Anote Tong purchased over 5,000 acres of land on Fiji, ostensibly to create a new home for a portion of Kiribati’s 103,000 inhabitants. The project was challenging, as Ilan Kelman reported in Difficult decisions: Migration from Small Island Developing States under climate change, “many unknowns remain in terms of whether or not that land is suitable for resettling everyone from Kiribati, on top of the uncertainties regarding the need for and speed of any migration.” Nonetheless, Tong, who was regarded as the most forward thinking of island nation leaders, was convinced that regardless of efforts to restrict emissions in the industrial nations, the rise in water levels was unstoppable, and the consequences for Kiribati, inevitable. François Gemenne, an academic specializing in migration told The Guardian that, “The government has launched the ‘migration with dignity’ policy… The aim is to avoid one day having to cope with a humanitarian evacuation.”

But a planned migration for the Kiribati appears to have been set aside for now, as a 2016 change of government upended former President Tong’s strategies entirely. The new president, Taneti Maamau, has chosen instead to build economic infrastructure and industry as quickly as possible, promoting fishing, resort building and tourism, all with the help of multinational corporations.

Another island nation, Tonga, is currently expiring catastrophic losses through combined climate change and government negligence. Like the Kiribati, Tongan peoples have a complex belief system: part of their ancient understanding of the world was based upon relationships to the stars and constellations that are only now beginning to be explored and documented. Regrettably, low-lying ancient sacred sites in Tonga that appear related to ancient ritual practices are inundated. Worse, ancient Tongan stone monuments are being deliberately bulldozed by the government to make way for shoddy housing developments – in what is actually a natural swamp.

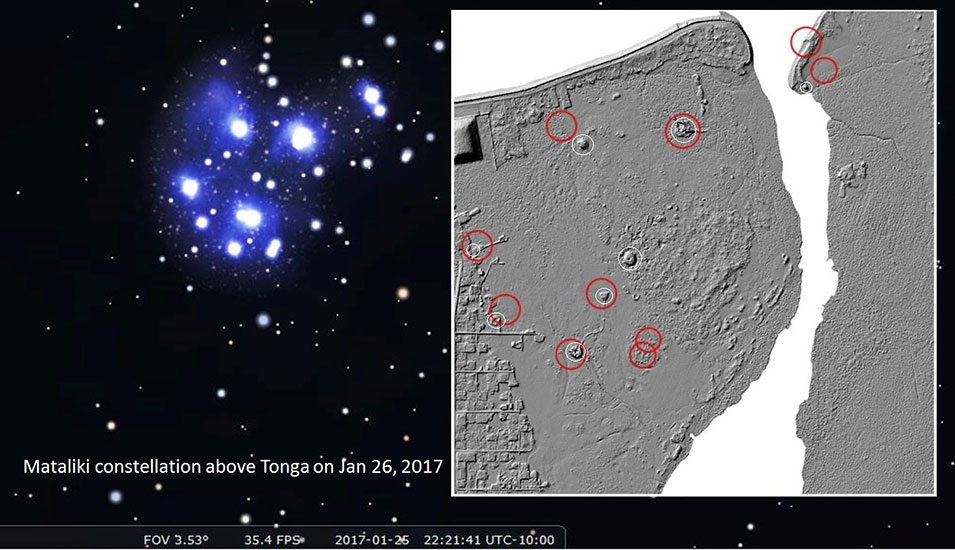

A possible correlation between the layout of the ancient complex of pigeon snaring mounds and walkways on the lagoon edge of Tongatapu and the Associated star constellation Mataliki (Pleiades). Compilation images courtesy of Shane Egan and the Tonga Heritage Society. Matangi Tonga Online.

Canals have been dug through previously untouched low-lying areas areas holding the ancient stone platforms and walkways belonging to early ritual sites called Sia. These Sia functioned both for pigeon-snaring, a royal sport in Tonga, and also associated with the Tongan creation story. Researchers Ka’ili and Shane Egan have suggested that there is a relationship between the ancient stone circles and platforms and the appearance of the Pleiades in the Tongan night sky. They believe there is a possible correlation between the positions of the mounds and the constellation, which was used by ancient Tongan navigators to cross the seas. Rising sea levels are expected to even more frequently inundate these formerly scared areas, and render the shanty-towns uninhabitable.

Climate changes have already exposed the vulnerability of low-lying islands and fragile reef ecosystems in other island nations. Tiny states in the Indian and Pacific Oceans have had to make difficult decisions because of the immediate impact of climate change on their populations. Tuvalu is a similar island nation to Kiribati and is struggling with similar issues of a changing land mass and impacts to traditional culture. According to Laura Corlew, in The Cultural Impacts of Climate Change: Sense of Place and sense of Community in Tuvalu, A Country Threatened by Sea Level Rise, community leaders and cultural experts explained that it would be difficult, if not impossible to maintain Tuvaluan culture when not in Tuvalu. “A person”s home island is at once their identity, their family, their community, their pride, and their responsibility.” (page 12)

In the Marshall Islands, there are reports of burial sites washing away to the sea. This is a particularly disturbing development for Marshall Islanders because, as the website Countries and Their Cultures notes, in the Marshall Islands, “Death represents the passage to becoming a non-corporeal ancestor, a being who continues to interact with community members, but one for whom the last vestiges of one’s body are “planted” to become a part of the soil which has already been reshaped by the energies of one’s lifetime.”

Tombstones in the courtyard of the Old Friday Mosque or Hukuru Miskiiy (1656) in Male, Maldives. Tombstones with pointed tops are for males, those with rounded tops for females. The small buildings are family mausoleums. Author: David Stanley, Nanimo, Canada, 16 December 2016, Wikimedia Commons.

The Maldives, which are made up of 1,100 islands in the Indian Ocean, are on average only 1.3 meters above sea level. The Maldives government predicts that the entire island nation will be disappear under the waves in as little as 30 years. The best known historic sites on the Maldives are a group of intricately carved Coral Stone Mosques that are over 800 years old. There are also hundreds of prehistoric, Buddhist, and Hindu archeological sites on the islands. (However, at this time, the Buddhist historical sites are more threatened by Islamic extremism than by climate change.)

Dozens of other island nations are facing similar issues as they deal with a changing climate that places their cultural heritage in peril. Former Maldives President Mohamed Nasheed summed up the sentiment of many island peoples in his keynote address at the International Bar Association’s annual conference in Tokyo in 2014, saying, “We will leave behind the beautiful Friday Mosque, carved out of coral stone three centuries ago. We will leave behind the trees we grew up with, the sands we played on, the sounds we hear every day. The sea will claim those things, and with it, the soul of a people.”

Map of Oceania, Central Intelligence Agency, US.

Map of Oceania, Central Intelligence Agency, US.