Five years ago, on November 30, 2016, the US signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with Egypt to limit importation of ancient and ethnographic Egyptian art into the US. The ostensible purpose of the 2016 agreement was to reduce the incentive for looting in Egypt. The legal basis for the agreement was a U.S. law, the Convention on Cultural Property Implementation Act, or CPIA. The CPIA created the Cultural Property Advisory Committee (CPAC), whose members review requests for cultural property agreements under the CPIA and make recommendations to the President. (Actually, the decision maker is an official at the State Department to whom the President delegates his authority.)

Egypt has now requested a five year renewal of import restrictions by the U.S. The CPIA provides for renewal of agreements with foreign nations after five years if the conditions that justified the original agreement still exist. To meet the legal requirements of the CPIA for renewal, Egypt needs to show that looting of both ancient and ethnographic art is a serious current problem in Egypt and that Egypt’s government has taken self-help measures over the last five years to protect and preserve cultural heritage inside Egypt. Under U.S. law, import restrictions may only be applied to archaeological artifacts of “cultural significance” and important ethnographic items from a non-industrial society. CPAC will need to make determinations that U.S. import restrictions would be of substantial benefit in deterring looting in Egypt, that less drastic remedies are not available, and that the import restrictions will be in the interest of the interchange of cultural property among nations for scientific, cultural, and educational purposes.

Site of the excavation of Heliopolis, 2015. Courtesy of the Egyptian Museum Georg Steindorff, University of Leipzig, Germany.

As part of the original agreement, Egypt was also obligated to “use its best efforts to preserve its heritage,” to “inventory its collections in museums, storerooms, and historic sites consistent with established international professional standards” and to “endeavor to build fruitful relationships with Egyptian civil society groups concerned with protecting and preserving Egypt’s cultural heritage.” Egypt was also to report to the U.S. government “on the implementation of the measures agreed to in this MOU” to determine if it should be renewed.

On March 3, 2021, the Committee for Cultural Policy (which publishes Cultural Property News) and Global Heritage Alliance submitted joint written testimony on Egypt’s request to the Cultural Property Advisory Committee. A slightly shortened version of this testimony is below. The CPAC committee will meet on March 17, 2021 at the Cultural Heritage Center at the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs at the Department of State to consider both the renewal of the MOU with Egypt and a new request for import restrictions from the Government of Albania.

For background on the operation of the Cultural Property Advisory Committee and how it has indefinitely renewed virtually all import restrictions for the last thirty years, see CPAC- Building a Wall Against Art on this website.

Summary

In 2016, over the strong objections of the U.S. museum community,[1] the United States and Egypt entered into a Memorandum of Understanding restricting import of undocumented Egyptian antiquities and ethnographic objects, including the possessions of Egypt’s persecuted Christian and Jewish communities.[2] The Government of Egypt has renewed this request but has not made public the facts justifying the renewal under the CPIA.

In response to past requests from source countries for import restrictions, CPAC’s deliberations have focused on the art market, particularly on claims from archaeologists and anti-trade advocates that a U.S. art market in looted objects is a primary cause of site destruction today, even if there is little or no evidence of recently looted artifacts being sold. Presenting the facts and verifiable history of the trade in Egyptian antiquities is therefore of great importance in determining whether looting today– since, by law, today is what the CPIA is concerned with – or if lawful export in the more distant past is the source for materials in the current market.

Renewing the Egyptian MOU is Contrary to Fundamental U.S. Public Policy

The renewal request from the Arab Republic of Egypt also raises serious public policy questions particularly relevant to a determination CPAC must make that import restrictions are in the public interest. These policy questions include but are not limited to:

- U.S. domestic concerns that restrictions could not be implemented fairly by U.S. Customs given the lack of available documentation of lawful export by Egypt and Egyptian authorities’ false claims about past unlawful export,

- the limitation of public access to ancient materials and uncensored information regarding art and history resulting from an import embargo with a country that controls what can be published by archaeologists who work there,

- the specific harms to dispossessed religious communities in the U.S. resulting from approving Egypt’s nationalist claims to the ancient and ethnographic heritage of religious minorities, and

- the social and geopolitical impact of a U.S.-Egypt bilateral agreement that effectively approves not only of the El-Sisi regime’s use of cultural heritage as a tool of its repressive, ultra-nationalist cultural policies, but which accepts its violations of human, civil, and religious rights without criticism or comment.

It is inconsistent with the general interest of the U.S. and the international community in the interchange of cultural property among nations for scientific, cultural, and educational purposes to renew a cultural property agreement with the brutal, dictatorial El-Sisi regime. It is especially dangerous to do so when the regime uses the agreement as a token of U.S. support, to bolster its domestic political standing and to counter U.S. and international criticism of its appalling human, civil and religious rights record.

Renewal of the US-Egypt agreement would not be consistent with the core US foreign policy objective of encouraging international civil society development and freedom of cultural and other forms of expression. Agreements and renewals should be based upon the compliance of requesting nations with fundamental American and international values respecting the rule of law and individual rights, including cultural freedoms, freedom of religion, speech, and assembly.

Giulio Regeni, photo Asiaecica, Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Egypt, under President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi, has been deservedly criticized for its human rights abuses, murder, forced disappearances, sexual abuse and torture of activists, political prisoners, and ordinary citizens whose opinions or way of life differ even slightly from what the El-Sisi government considers ideal.[3] How can this be reconciled with respecting cultural rights?

The Egyptian government human rights violations include the torture-murder in 2016 of Cambridge University PhD student Giulio Regeni for collecting information for his thesis on trade unions[4] and the incarceration, disappearances and summary executions of hundreds of its own politically active citizens, to actions that would be ludicrous if the consequences were not so serious. In 2020, the Egyptian government, in what was described widely as a “culture war,” arrested nine young women and has sentenced several already to lengthy prison terms on charges of violating “family values” for lip-syncing in Tik-Tok videos.[5]

Renewal of the US-Egypt agreement is not consistent with the core US foreign policy objective of opposing persecution and discrimination of individuals and religious institutions for religious reasons. An MOU with Egypt would condone its government’s seizure of the personal property of its forcibly displaced Jewish community and its denial of Jewish and Christian religious minorities’ claims to movable and immovable property, which has been confiscated or forcibly abandoned.

Renewal of the US-Egypt agreement would not be consistent with the U.S. and international interest in the halting of government corruption surrounding antiquities, ensuring responsible caretaking of archaeological resources, and upholding of site security at archaeological sites. All of these responsibilities are essential tasks for a government’s protection of its own cultural heritage.

The Egyptian government uses the MOU with the U.S. for domestic and international political purposes to demonstrate U.S. support for its authoritarian regime. Yet the El-Sisi government has one of the worst human rights records in the world.[6] It would be an unconscionable step for CPAC to recommend renewal, to ignore the Egyptian government’s corruption and neglect of its monuments and archaeological sites, to validate its claims to the cultural heritage of religious minorities forced from its borders and to give cover to the El-Sisi regime’s appropriation of Pharaonic heritage for political purposes.

In sum, it would be contrary to fundamental U.S. public policy for CPAC to recommend the renewal of the Memorandum of Understanding with the Government of the Arab Republic of Egypt after the current five-year period expires.

The vast majority of Egyptian objects in global circulation were exported during a century and a half of tolerated, and then permitted export. The Egyptian government denies the fact of some 70 years of fully licensed, legal export and continues to seek repatriation of all objects, placing U.S. authorities in the position of seizing goods that were lawfully exported simply because their past ownership is insufficiently documented.

Antiquities have been lawfully exported from Egypt in greater numbers than any other type of ancient art in circulation. Antiquities were exported under both Ottoman and colonial rulers, as well as shared out in partage agreements with archaeologists. Even given restrictions on paper on export in the 19th century, selling antiquities found in the ground has been a legal, even a licensed, business in Egypt for much of the last 200 years, and many hundreds of thousands of objects have travelled in trade around the world in that time. An important academic study by Danish scholars Frederik Hagen and Kim Ryholt, The Antiquities Trade in Egypt 1880-1930, The H.O. Lange Papers,[7] is a comprehensive study of the antiquities markets in Cairo, Kafr el-Haram at Giza, Qena, Luxor, Alexandria and other locations. This study makes clear the vast scale of the antiquities trade from the early 19th century up to the cessation of official licensing in 1983.

The first significant trade coincided with the invasion of Egypt by Napoleon Bonaparte and the development of early European studies of Egypt by scholars such as the philologist Jean-François Champollion. From the mid-19th century until the antiquities trade became licensed in 1912, a network of Egyptians and foreigners acted as quasi-diplomatic “consular agents” who supplied antiquities to foreign buyers, often on a grand scale. These agents contracted with diggers and dealers and removed hundreds, even thousands of items at a time for major foreign buyers.[8] Excavation permits were also issued to antiquities dealers by the 1880s and formalized under law in 1891. A portion of all excavated items could be exported after division with the Egyptian Antiquities Service. Even in 1862, tourist demand in Egypt was such that,

“all antiquities are dearer in Thebes than in London, and less likely to be genuine… the most absurd sums are given by travelers for what dealers at home would be only too glad to get rid of for a trifle.”[9]

This upside-down market also resulted in the mass production of fakes from the early 19th century onwards.

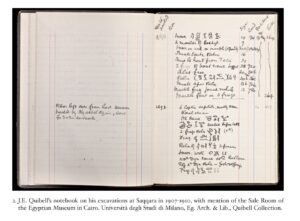

Photograph of two pages from the Register of the Sale Room of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. Università degli Studi di Milano, Eg. Arch. & Lib., Bothmer Collection. Plate 1, Forming Material Egypt: Proceedings of the International Conference, London, 20-21 May, 2013, Patrizia Piacentini, “The antiquities path: from the Sale Room of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, through dealers, to private and public collections. A work in progress.” EDAL IV, 2013/2014.

The Egyptian government’s Antiquities Service built very large collections of objects through excavations and the division of archaeological spoils. The Antiquities Service established a salesroom in the 1880s, first selling surplus items from museum storage, but later making archaeological expeditions specifically to supply a salesroom in the Cairo Museum with objects to sell. Sites known as good sources for bronzes and amulets were among those quarried by the Antiquities Service. [See Ex. 3, Saleroom of the Antiquities Service, Ex. 4, Pages from the Register of the Saleroom, Ex. 5, Notebook on Excavations at Saqqara in 1907-10 with reference to the Saleroom, Ex. 6. Showcase, 1913]

A 1912 Egyptian law formalized the trade in antiquities, enabling licensing of authorized dealers. In its first year, some 200 applications were received for licenses. Only about 100 applicants qualified to receive the licenses, and it appears that this was the average number of licenses active each year. The highest numbered license was #127, but the same numbers were reused for subsequent licensees. A chief purpose of the licensing process was to ensure that taxes were paid on the items sold. Receipts were issued by the licensees but as taxes were assessed by the shipping case, not the contents, the permits provided only vague descriptions, such as a dozen or a hundred or more “Egyptian Antiquities over 100 years old.”[10]

The largest numbers of objects were exported in the 20th century by the several hundred art dealers in Cairo and Alexandria licensed by the government between 1912 and 1983 to sell antiquities. These antiquities shops became key suppliers to foreign museums and collectors. They sold thousands of scarabs, pieces of jewelry, glass and ceramic vessels, statues and statuettes, bronzes, papyri, coffins and coffin lids, complete mummies, and other objects each year. A number of important shops were located adjacent to the chief European hotel in Cairo, Shepheard’s, while nearby, a veritable palace filled with many thousands of antiquities was used as his showcase by one of the most important Egyptian dealers, Louis Nahman. Many smaller antiquities shops were located in the Muski and other areas welcoming to foreigners in Cairo and nearby Giza.[11]

Some Egyptian dealers traveled to Europe to buy antiquities at auction; one of these businesses was Kalebdjian Freres in Cairo, which operated between 1900 and 1956. The brothers opened a saleroom in Paris in 1905, but they also purchased Egyptian artifacts in Paris and London at the auction sales of the Amelineau Collection (1904), the Hilton Price Collection (1911), the MacGregor Collection (1922), and the Hearst Collection (1939), and then brought their purchases back to Egypt to sell them at a higher price.[12], [13]

Showcase on the first floor of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, probably 1913. Università degli Studi di Milano, Eg. Arch. & Lib., Varille Collection. Plate 23, Piacentini. “When the Museum moved to Midan Ismailya — now Tahrir, in the first years of the Twentieth century, the Sale Room was located in room 56 of the ground floor, accessible from the western entrance…”

(pls xvii-xviii). Id. at 116.

Ignoring this history, the present Egyptian government has often blamed Western art dealers and collectors who hold historical inventory for current looting inside Egypt. Such claims have been disputed by Egyptian officials such as former Antiquities Minister Mamdouh al-Damaty, who has stated that most Egyptian artifacts abroad had been legally exported,[14] and even the notoriously repatriation-happy Zahi Hawass has admitted that about 70% of Egyptian antiquities exhibited at European and American museums are considered to have come out of Egypt legally as a result of partage agreements.[15] Nonetheless, blanket claims of national ownership and demands for repatriation are regularly made by Egypt’s government when Egyptian objects are publicly sold.[16]

Subsequent to the imposition of export restrictions under the 2016 MOU, some important Egyptian antiquities with documentation of ownership have continued to be imported into the U.S. from countries other than Egypt. (This is far more likely in the case of high value objects for which ownership records are likely to exist.) However, the documentary requirements for the majority of Egyptian objects in circulation for entry to the U.S. cannot be met, particularly for low-value items and coins, due first to the failure of the Egyptian government to sufficiently document their lawful export and the lack of subsequent documentation of ownership outside of Egypt. [See: Ex. 10: Imports to the United States, Egypt Country of Origin – all art 2008-2020, current date 03/02/2021]

Egypt’s government has not followed its own antiquities laws or consistently enforced them. The U.S. should not be forced to enforce past Egyptian laws that the Egyptian government often ignored.

Egyptian cultural officials have often stated that laws dating to the mid-19th century establish that virtually all Egyptian antiquities in circulation have been “stolen.” While laws relating to antiquities date to the early 19th century, export restrictions were much more limited, even on paper and despite legal restrictions, export was not only permitted; it was also extremely common.

The first Egyptian legislation, the 1835 High Order of Muhammad Ali, attempted to regulate the rampant destruction of sites in the early 19th century by unrestricted excavation and the wholesale removal of monuments, but the controls set forth in that law were little regarded. The “museum” created by the 1835 order failed, as its collections were repeatedly depleted by being given away to visiting foreign dignitaries.

In March 1869 regulations for excavations of “antiquities items” were issued defining what could be taken out of the country – establishing a division of objects. Later rules regarding partage were amended to apportion objects differently, to recognize duplicative objects as allowed for export and to specifically grant the Antiquities Service first rights to choose.

In the law of March 24, 1874, underground/undiscovered antiquities were stated to be the property of the government. Article 34 stated that antiquities seized from smugglers were to be confiscated. Under the law of August 12, 1897, Article 2, antiquities involved in unlawful activity were deemed the property of the government. Despite these laws apparently curbing the illegal trade:

“At the dawn of the Twentieth century, the Sale Room was very active, and the “duplicates” found during the excavations were regularly sold to finance the activities of the Antiquities Service… To increase its income and try to reduce robberies and unfettered trade, the Antiquities Service decided to sell complete funerary chapels discovered in Saqqarah to foreign museums, as those in New York, Chicago, London, Berlin, Paris, Bruxelles.”[17]

The June 12, 1912, Law No. 14, officially recognized the existence of a busy, ongoing antiquities trade. Antiquities were prohibited from export without a license/certificate of export granted by the Antiquities Department. Antiquities exported without a license could be seized and confiscated by the government.

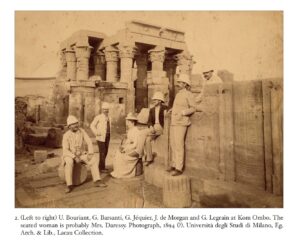

Archaeologists, group photo, U. Bouriant. G. Barsati, G. Jequier, J. de Morgan and G. Legrain at Kom Ombo. The seated woman is probably Mrs. Daressy, circa 1894, Universita degli Studi di Milano, Eg. Arch. & Lib., Lacau Collection.

The export of certain rare items was hoped to be reduced through passage of Law No. 215 of 1951. It required written approval of the Department of Antiquities for export, which was to be granted only if multiple similar items were already present. This law increased the penalties for theft or smuggling of antiquities. A Department of Antiquities review process was through committees including the director of the concerned museum, a museum curator, and a representative of the Department of Customs.

The legal trade and export of antiquities finally came to a halt after promulgation of Decree No. 14 of 1979, issued after a March 29, 1979 decision by the Board of the Egyptian Archaeological Organization, stated that the “granting of license to individuals for the export of antiquities, irrespective of their source outside the Arab Republic of Egypt” would end. Nonetheless, dealers were given a year or more to deal with their existing stock.

The August 11, 1983 Law No. 117, “Issuance of Antiquities Protection Law,”[18] actually ended licensing and established the Egyptian Antiquities Authority as “supervisor of all archaeological affairs at museums, store[house]s, archaeological and historical places, even if discovered by accident.” All antiquities are deemed “public property” and possession of such antiquities is prohibited, with the exception of antiquities whose ownership was already established when the law came into effect in 1983.[19] An “antiquity” under the Egyptian law includes any movable or immovable property that is “a product of any of the various civilizations or any of the arts, sciences, literatures, and religions of the successive historical periods” from prehistory until “one hundred years before the present.”[20]

Article 5 of the 1983 Law No. 117 set scientific standards for licensing domestic and foreign archaeological expeditions. Article 6 made all antiquities public property except waqfs (waqfs are Muslim trust organizations, often holding religious buildings and other property). Article 7 prohibited trade in antiquities, giving current tradesmen a one-year grace period in which to dispose of their stock, after which anything remaining would be subjects to the law’s provisions on the possessors of antiquities. Article 8 required owners of antiquities to notify the Egyptian Antiquities Authority and to preserve the antiquities until the Authority registered them. Even after this, the possessors of antiquities could obtain approval of the Authority for the disposal of antiquities so long as they remained within Egypt. Inheritance of antiquities was permitted. The Authority could take possession of antiquities from tradesmen “in return for a valuable consideration.” Under Article 24, the finder of a movable antiquity must report it to the nearest administrative authority within 48 hours. It states that some compensation might be paid.

There are serious questions whether the Government of Egypt has utilized the powers and responsibilities enumerated in the 1983 law to actually enforce restrictions on domestic trade and to document its inventory of ancient objects and the inventories in the many known collections of antiquities that have continued, even after official “registration” was required, to exist in private hands.

Importantly, in Article 26 of the 1983 law, the Antiquities Authority has the responsibility of “enumerating, photographing, drawing, and registering immovable and movable antiquities together with gathering information pertaining to said antiquities in registers.” Article 28 requires that antiquities be kept together and “all shall be put at the authority’s museums and stores,” and the Authority is tasked with “supervising the necessary means of protection and security for said contents.” Article 29 charges the Antiquities Authority with “taking care of antiquities, museums, stores, and archaeological sites and areas and historical buildings besides the guarding of such through competent police, and special watchmen and guards.”

J.E. Quibell’s notebook on his excavations at Saqqara in 1907-1910, with mention of the Sale Room of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. Università degli Studi di Milano, Eg. Arch. & Lib., Quibell Collection. Id. Plate 2.

One rarely used provision under the 1983 law granted the Antiquities Authority the ability to exchange movable and duplicative antiquities “with states or museums or scientific institutes whether Arab or foreign.”

The most frequently abused provision in the 1983 law had to do with the failure of the authorities to preserve and protect archaeological and historical sites. Destruction or pulling down “real antiquities” was not permitted under the law. Neither was expropriation of lands or real estate by the state. However, individually owned lands could be expropriated for their archaeological importance. Although no one is allowed to build constructions, roads, canals, establish cemeteries or cultivate on archaeological sites under the 1983 law, these abuses are frequent.

We note that the April 2018 amendments to Law No. 117 of 1983, punished theft or hiding of antiquities, including registered antiquities, owned for the purpose of smuggling, from imprisonment for 7 years and a fine of not more than LE 500,000 (a tenfold increase) to life imprisonment, with fines of one million to five million Egyptian Pounds. The punishment for destruction of antiquities or damage to monuments or illegal digging increased from 1 year to life imprisonment. According to Minister of Antiquities Khaled El-Enani, these penalties would fully protect the antiquities in Egypt.[21]

Egypt’s has failed to protect its own cultural property under its own laws.

While press reports of unauthorized digging by people looking for antiquities have increased in recent years, that in itself may reflect other factors – lack of funding by Egypt’s government for site security, desperation from want of employment in tourist sites rich in archaeological materials, and popular beliefs among the uneducated that antiquities are likely to contain hidden gold. Altogether in 2019, the government reported that 930 individuals had been arrested for opportunistic looting in upper Egypt,[22] where the looting is said to be the worst. Given Egypt’s highly censored press, this reporting also indicates an increased interest on the part of the government to highlight looting for objects as the cause of site destruction, rather than the equally widespread destruction of sites through unauthorized and unchecked building and road construction.

Much criminal activity related to antiquities in Egypt is extremely petty, although one recent case in which a former diplomat was convicted in absentia involved over 20,000 objects, several hundred times the number found in more typical cases:

- 2016 – Authorities arrested three men selling pieces taken from Pyramids and selling them to tourists.

- November 2017 – Tourism police seized 464 artifacts, including Ushabtis and statues made of paste from antiquities merchants in Fayoum.

- April 2018 – Cache of mostly fakes seized by police before smuggling from Minya

- August 2017 – An attempt to smuggle 124 objects from a Ministries of Antiquities storage facility in Maadi was foiled.

- December 2017 – 29 ancient coins were seized from an Egyptian airline passenger en route to France.[23]

- 2017-2018 – Italy seized objects apparently from a large cache of private antiquities in Egypt. The case implicated a former Italian consul and close family members of officials in the former Mubarak government.[24]

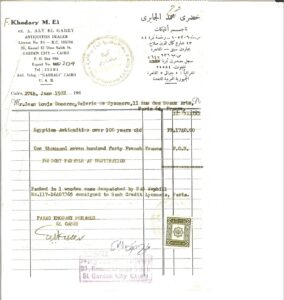

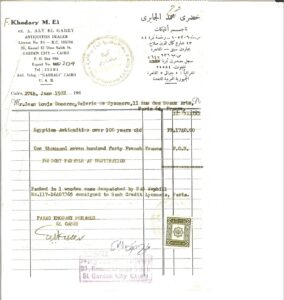

Export permit for Egyptian antiquities, dated 1972, Khodary M El Gabry, Courtesy International Association of Dealers in Ancient Art (IADAA), Note that licenses contain no description or pictures, hence they were not retained and are very rare today.

Egypt does not provide the public with detailed documentation of arrests or convictions for antiquities looting, adequate records of what is seized from travelers or attempts at illicit exports. All information is partial or anecdotal. This lack of information is regrettable, especially given that, at least in the press, actual seizures of objects seem to be better reported by authorities outside Egypt than within it. “Sometimes I’m sure that inspectors are complicit, and the police are frequently complicit and in some cases the military is complicit because they fly things out in military planes,” a foreign archaeologist told ABC, speaking on condition of anonymity.[25]

Egypt has failed to curb an epidemic of do-it-yourself home excavations. Clandestine home excavations, where people dig under their houses, have increased dramatically in Upper Egypt during the pandemic. The loss of jobs, especially in the archeological tourist sector, and the myth of easy money from artifacts have contributed to the illegal excavations in regions where there is a popular belief among the uneducated population that many antiquities contain hidden gold. Unfortunately, the digging has frequently turned deadly when poorly constructed tunnels collapsed.[26]

The Egyptian government has largely ignored the corruption of officials who allow housing, factory, road building and other construction in vulnerable areas where sites are known to be located – even turning archaeological sites into garbage dumping grounds. A striking example is right outside of Cairo:

“Another such site used as dumping ground was the Masalla section of Al Matariya district, which is the location of ancient Iwn or Heliopolis and contains one of Egypt’s few remaining freestanding obelisks. The area behind the Dynasty XII obelisk of King Senusert I had been turned into a garbage dump picked over by sheep and goats, and a nearby spot where remains of a Middle Kingdom temple lies was used as a swimming pool for dogs.” Subterranean water had leaked into the archaeological pit where the remains lie, filling it with water, and dogs are taking a plunge to escape the summer heat.” [27]

For many years, poor storage methods, disabled security devices, and falsified and missing documentation have characterized Egyptian antiquities storage facilities. Archaeologist Monica Hanna was quoted in Al-Monitor, saying, “…this campaign can only succeed if all obstacles are addressed. This requires making archaeological artifacts available to researchers and academics for scientific publication. When artifacts are documented in international libraries, their recovery becomes easier if stolen.” She added, “The other crisis is that there are thousands of artifacts not registered with the ministry of antiquities, and there are archaeological warehouses that have never been inspected.” [28]

The work that has begun deals only with a fraction of what sits in store. In July 2017, Gharib Sunbul, head of the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities’ central administration for maintenance and restoration, said that an inventory of 5,000 artifacts was almost complete. Although 5,000 artifacts represents a tiny fraction of the countless antiquities estimated to be held in warehouses throughout Egypt (when 200,000 were moved, even this number was said to have been a small fraction), the inventory signaled a beginning to the process of protecting Egypt’s long neglected stored cultural heritage from deterioration and theft. As the Grand Museum project has been given priority and revenues have dropped, this work is effectively on hold. Deterioration and destruction of objects from poor storage methods is a bigger issue than theft. Many artifacts are poorly packaged and placed in wooden boxes, precariously stacked one on top of the other, in facilities where conditions allow water, heat, insects and even sewage to damage the objects. Reports of artifacts placed directly on dirt floors are not uncommon, and neither are the stories of spiders, mice and other insects making nests in and meals of leather, paper and wooden antiquities.

“There are at least 72 archaeological warehouses in Egypt [other writers guesstimate the number at 200]. Of them, 35 are museum warehouses, 20 are expedition warehouses and 17 are smaller on-site warehouses spread across Egypt’s . Only 14 warehouses out of 72 have ever been inspected.”[29]

Finally, Egypt does not enforce its laws requiring owners of antiquities to register and turn over collections, leaving them in place and providing a primary source of objects available for unlawful export without any current illicit excavation. A general failure to enforce its own laws can also be measured by Egypt’s low standing in the Corruption Perception Index compared to its level of urbanization and industrial development.[30]

Egypt has declined to collaborate in projects to enable the public to distinguish between lawfully exported and illicit objects.

As we have noted, the Egyptian export licenses available as proof of legal export are usually summaries of large lots and fail to itemize or describe items. It is well recognized that Egyptian export licenses are inadequate to identify specific legally exported objects. Another documentation mechanism is clearly required in order to distinguish between objects already in circulation in the global market and items stolen from storage facilities and looted from sites in order to prevent them from reaching the market.

Export permit for Egyptian antiquities, dated 1972, Khodary M El Gabry, Courtesy International Association of Dealers in Ancient Art (IADAA), Note that licenses contain no description or pictures, hence they were not retained and are very rare today.

Unfortunately, even today, Egypt rejects collaboration with dealer organizations to document and track Egyptian antiquities in order to distinguish between objects long in circulation and recently looted objects, effectively removing an opportunity to try a “remedy less drastic” than import restrictions.

For example, in late 2017, the British Museum announced the creation of a database of Egyptian and Nubian antiquities in circulation in private collections and on the international art market, known as CircArt.[31] Funding for the project was encouraged by the Antiquities Dealers Association (ADA)[32] and the International Association of Dealers in Ancient Art, (IADAA),[33] both of which were active partners in its development. The IADAA stated that it viewed the project as essential for “reducing crime; enhancing due diligence; and promoting constructive relations between collectors, dealers/auctioneers, museums, law enforcement and antiquities officials.” IADAA’s endorsement in June 2017 opened the door to a £998,769 grant for the project.

However, the Egyptian government objected to acknowledging any art trade’s association with the project, even insisting on removal of the logos of trade professional organizations and auction houses from the original British Arts Council press announcements.

The database was originally designed to be “free for the public to search” and its purpose “not to locate looters or thieves, but it is rather to help establish the provenance of legitimately collected artefacts,” but the Egyptian government declined to make the database publicly accessible, so it cannot now be used to identify works of questionable provenance by the public.

Egypt has largely failed to engage with museums in the U.S. except to sell Pharaonic exhibitions with extraordinarily high rental fees.

Despite its vast collections, Egypt has done little to further the circulation of Egyptian artworks in U.S. and other international museums or to allow long term loans of archaeological and ethnological material. Egyptian cultural monies and energies are overwhelmingly dedicated to the Grand Egyptian Museum project and other projects celebrating Pharaonic greatness. The cost of the Grand Egyptian Museum has now escalated to well over U.S. $1 billion (estimate as of October 2017 and still increasing), 75% of which has been raised through loans from Japan to the Egyptian government.[34] In September of 2020, the Egyptian government announced the opening of three new and renovated museums: the Kafr el-Sheikh Museum (Pharaonic and biblical art), Royal Chariots Museum in Cairo (royal chariots used by kings and rulers throughout Egyptian history), and the renovated Sharm el-Sheikh Museum (now including Pharaonic and other ancient materials). The Egyptian government’s announcement of the museum openings said they were in celebration of Egypt’s “6th October 1973 victory”[35], the start of the 6-Day War which began with Egypt’s surprise invasion of Israel on Yom Kippur.[36]

‘Cultural exchange’ from Egypt amounts to ‘blockbuster’ exhibitions designed to fundraise for the Grand Egyptian Museum now and promote international tourism to it afterward. The exhibition “Tutankhamun, the Golden Age of the Pharaohs,” which had four U.S. venues in 2005 ($30 per person tickets in Los Angeles), charged a $5 million flat fee to each museum venue.[37] That exhibition was commercially packaged by Arts & Exhibitions International and National Geographic.

Saleroom of the Antiquities Service in the Cairo Museum, 1960s. Source: International Association of Dealers in Ancient Art (IADAA).

Another show of King Tut’s treasures, “Tutankhamun: Treasures Of The Golden Pharaoh,” traveled to Los Angeles, Paris, and finally to the Saatchi Gallery in London from 2018 to May 2020, when Covid forced museum closures.[38] This exhibition is an updated rendition of the King Tut show of the late 1970s that opened Egyptian authorities’ eyes to the commercial possibilities of exhibitions (and generated a hit single for comedian Steve Martin[39]). Tickets were about $27 individual, $65 family, the high prices due to the hefty fees charged by the Egyptian government to hosting museums.

More Egyptian gold will be featured in another expected moneymaking exhibition announced by Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, “Ramses and the Pharaohs’ Gold,” November 2021 – January 2025. The show will open at the Houston Museum of Natural Sciences, then move to the De Young Museum in San Francisco to Castle Hall in Boston, the London Exhibition Hall in London and La Felette Hall in Paris.[40]

Egypt’s international cultural property policy ignores the human and cultural rights of religious minorities both within Egypt and in the Diaspora.

The Cultural Property Advisory Committee has approved MOUs not only with Egypt, but also with other Middle Eastern and North African nations – all of which have been granted practically all-encompassing import restrictions on ancient and ethnographic materials. These form a disturbing pattern of unduly comprehensive import restrictions with Middle Eastern nations. The restrictions exclusively benefit the nation’s governments and their property claims over cultural and religious artifacts— at the expense of the ownership rights and basic human rights of individuals in minority populations.

On December 9, 2018, eighteen Jewish organizations led by JIMENA and including B’nai B’rith International and the World Jewish Congress North America sent a letter to U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo[41] to protest the inclusion of objects of Jewish heritage in cultural property agreements with Middle Eastern and North African nations. Jewish and Christian ritual objects, including antique Torah scrolls, tombstones, books, Bibles and religious writings are covered under these agreements. Family heirlooms, furnishings, and even clothing and jewelry broadly described as “Ottoman” are also blocked from entry, although these objects are hardly objects of national heritage, but instead were typical handicrafts manufactured for general use by all the urban inhabitants of Middle Eastern urban communities. The letter states, in part:

“The Cultural Property Implementation Act (CPIA) was enacted to deter the looting of archeological sites by enacting temporary import restrictions on significant cultural items as part of a multilateral effort. Unfortunately, over time these restrictions have expanded beyond both the law’s intent and its legal authority.

“We recognize the importance of these MOU agreements in deterring the pillaging of archaeological and ethnological materials. However, an additional goal of these agreements, as noted in the Convention on Cultural Property Implementation Act, is to, “increase international access to cultural property.” This has a particular relevance with regard to Jewish heritage, which encompasses both moveable (e.g., Torah scrolls, ritual objects, libraries, communal registers) assets and immovable (e.g., synagogues, cemeteries, religious shrines) assets. Regrettably, it is not safe – and in many cases forbidden by national law – for Jewish refugees from Arab countries to return to the countries that exiled them.

“…[R]equesting MOUs should be asked to present an inventory of remaining Jewish moveable and non-movable patrimony and an account of what they are actively doing with respect to the care of synagogues, cemeteries and other sites and items of Jewish and Christian heritage.

“The recent statement by the Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary for Near East Affairs, Joan Polashick, that the State Department is working on an additional five MOUs with Middle Eastern and North African nations makes it essential that a policy is in place that protects Jewish and Christian heritage by explicitly excluding them from any import restrictions and rejecting any state claims to individual and communal property.”[42]

Inside of the Synagogue of Moses Maimonides before its renovation in 2010, Jewish quarter, el-Muski, Cairo, Egypt, 27 February 2006.

Despite the serious concerns raised in this letter, the “additional five MOUs” it references are already completed and only one excludes certain – but not all – items of Jewish heritage from its Designated List.

The Memorandum of Understanding between the United States and Egypt that entered into effect on November 30, 2016 not only included Jewish religious items, it also covered objects that would have formed the personal property and heirlooms of Jewish families who were denied the opportunity to take these items with them when persecution by the Egyptian government led to their forced emigration.[43] Like other Designated Lists from MENA countries accompanying the MOUs, its import restrictions are far broader than any evidence of actual trade could possibly justify.

The Egypt MOU’s Designated List of protected cultural objects includes “scrolls, books, manuscripts, and documents, including religious, ceremonial, literary, and administrative texts. Scripts include hieroglyphic, hieratic, Aramaic, Hebrew, Greek, Latin, Coptic and Arabic.”[44] Writings on a variety of materials, from wood to metal and stone that contain such languages are also prohibited from entry.[45] It should be noted that only Islam and Christianity are mentioned by name on the Designated List’s protected objects. Nonetheless, virtually all objects of Egyptian cultural heritage dating from the Predynastic period (5,200 B.C.) through 1517 A.D are included.[46]

What is particularly concerning is the devastating impact of national ownership claims on heritage of each country’s Jewish as well as other minority religious communities. These communities were severely persecuted in the 20th century, their goods and property seized , and many were forcibly expelled by these States’ governments.

One of the most powerful reasons to reject renewal of the Egyptian MOU is that Egypt’s government claims national ownership of Jewish and Christian heritage belonging to religious minority communities driven from Egypt[47] and demands return of Jewish and Christian religious artifacts through this renewal of the MOU with the U.S.

Zaoud el Mara, Jewish Quarter, Alexandria Egypt, 1898, stereoscopic photograph, B.W. Kilburn.

The Egyptian government has pursued a bifurcated path with respect to Jewish and Christian minority heritage. On the one hand, Egyptian Christians face periodic violence, damage and destruction of Church property and ongoing discrimination in daily life. Egypt’s once vibrant Jewish community has been reduced to a few elderly residents and access to Jewish records held by the Egyptian government is a serious continuing problem.

On the other hand, Egypt has spent considerable sums to restore badly dilapidated Jewish properties that no longer serve a religious function because there are so few Jews remaining in Egypt. The most striking example of this is the restoration of the original Maimonides Yeshivah dating to the 12th century and the adjacent Rav Moshe Synagogue, known as the Maimonides synagogue, a 19th century building on a site in Cairo that has belonged to the Jewish community since the 10th century. The reopening of the beautifully restored synagogue was, however, marred by cancellation of further celebrations by the then Director of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, Zahi Hawass, who stated that Jews were drinking wine and dancing inappropriately.[48] The better-known urban Jewish sites have for the most part been protected and guarded in recent decades under the auspices of the Egyptian government. They are designated by the Supreme Council of Antiquities as “protected” under Egyptian law. While the local Jewish communities’ original ownership the buildings is recognized, their contents cannot be removed and it is not known what will happen when the last of Egypt’s Jews has died, nor what will be the fate of the records of the community.

Egypt effectively denies access to these essential records of the Jewish community and refuses even to allow digitization for academic purposes. The Egyptian government has said for years that it would digitize the records in the Jewish Library of Cairo, but in 2016, the Cairo Post reported that the Cairo Jewish community’s leader, Magda Haroun, had called on the government to scan the records, saying the records were not properly stored and that she feared continuing neglect.[49] Haroun had asked the Biblioteca Alexandria to digitize the records but it had declined, saying the request needed to come from the Ministry of Antiquities.[50] It is essential for Jews in the Diaspora to be able to access these records, not only for purposes of scholarship, but because they contain the detail marriage and birth records necessary for the approval of marriage alliances among traditional Jewish communities. We note that Ms. Haroun has issued a public letter just this month that contains no criticism whatsoever of the Government of Egypt and fulsomely praises its friendly relations with the Cairo Jewish community, which now number five persons or less, all elderly women. Ms. Haroun’s comments, however sincere, and her appreciation that she is now able to pray in a synagogue owned and also used by the government for various non-Jewish community activities, does nothing to lessen the history of oppression, seizures of property, and attacks on Egypt’s Jewish community that led virtually its entire population of Jews to flee Egypt in the 20th century. Nor does it lessen the harm of denying access to records or the seizure of religious and community property left behind.

In July 2017, another major restoration project was announced; the Egyptian government stated in February 2018 that it has expended approximately $5 million dollars US to restore the Eliahu Hanavi Synagogue in Alexandria.[51] While reluctant to engage directly with Israel on heritage matters, the Egyptian government has been willing to discuss funding from American Jewish groups to restore and maintain Jewish heritage in Egypt and the tiny remaining Cairo community has received some American support.[52]

The nave of the Eliahu Hanavi synagogue in Alexandria. Author David Lisbona, Haifa, Israel, 2006, Wikimedia

After decades of fighting with Egyptian authorities, Egyptian Jewish activist Carmen Weinstein was unable to obtain assistance from the Egyptian government to prevent the inundation of Cairo’s primary Jewish cemetery with sewage water. Weinstein was finally buried in April 2013, far from her family’s water-soaked tombs.[53] The Egyptian government accepted funding in 2020 from the U.S. State Department’s Ambassadors Fund for Cultural Preservation (AFCP) for the conservation of the 9th century cemetery, one of the oldest Jewish cemeteries in the world.[54]

Christian as well as Jewish cultural heritage in Egypt is threatened, despite official government policies of protection. In January 2018, the U.S. called on Egyptian President Sisi to continue efforts to promote diversity and to remedy relations with Egyptian Coptic Christian groups.[55] Many Christian sites in Egypt have been severely damaged in the civil instability of the last decade. The Egyptian army has also been culpable. An Egyptian archaeological group reported in 2011 that the 5th century St. Bishoy monastery had been attacked by army forces in the Wadi Natrun, and at the Monastery of St. Makarios of Alexandria in Wadi el-Rayyan, in the Faiyum, a monk was killed and 10 injured.[56]

Restoration projects like that of the Red Monastery Church, which spanned a period of great unrest in the Middle East, including the rise of Muslim extremism, increased persecution of Coptic Christians in Egypt, and the Arab Spring, have shown that Egyptian officials can work together with minority religious communities. This project also demonstrated that the interests of foreign archaeologists and historians could willingly be circumscribed by the choices of the minority community – and the community itself left to determine how access would be allowed.[57]

That autonomy and community decision-making role is far more often neglected or denied. While officially, the value of Pharaonic, Islamic, Coptic, Christian, and Jewish heritage is acknowledged, there is little other public evidence that the Egyptian government recognizes the longstanding role of the Jewish or Christian population in Egypt. For example, when the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization partially opened in Cairo in 2017, it was reported that no Jewish items were placed on display.[58]

Cultural rights are human rights.

Within the 2016 MOU, the Egyptian Government promised to “endeavor to build fruitful relationships with Egyptian civil society groups concerned with protecting and preserving Egypt’s cultural heritage as represented in the Designated List.”[59] The Designated List of protected cultural property specifically notes that “such items often constitute the very essence of a society and convey important information concerning a people’s origin, history, and traditional setting.”[60]

The Designated Lists of restricted objects for Iraq, Syria, Libya, and Egypt all state the purpose of the United States’ implementation of the CPIA as “preserving cultural treasures that are of importance to nations from which they originate” and achieving a “greater international understanding of our [alternatively mankind’s] common heritage.”[61] This is, of course, a worthy goal—if application of this goal was not so difficult to reconcile with traditional notions of culture, property rights, and human rights—or so difficult to reconcile the content of existing MOUs with the requirements of the CPIA. The fourth requirement of the CPIA states that import restrictions on cultural property must be “consistent with the general interest of the international community in the interchange of cultural property among nations for scientific, cultural, and educational purposes.”[62]

We must then ask: what is the “general interest of the international community in the interchange of cultural property” that the CPIA requires CPAC to consider? To some scholars, the 1970 UNESCO Convention “globalized the concept that cultural property is worth protection on moral, not just economic, grounds.”[63] Others have noted that the protection of human rights is one of the central tenets of international art law.[64]

While there is not an internationally recognized “human right to cultural property” or “human right to cultural heritage,” international law does indeed recognize a “human right to culture.” Article 22 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that: “Everyone, as a member of society… is entitled to realization, through national effort and international cooperation and in accordance with the organization and resources of each State, of the economic, social and cultural rights indispensable for his dignity and the free development of his personality.”[65]

The UNESCO Declaration of the Principles of International Cultural Co-operation, (1966) echoes the same sentiment to protect “mankind’s common heritage” that the CPIA and the import restrictions seek to protect:

1. Each culture has a dignity and value, which must be respected and preserved. 2. Every people has the right and the duty to develop its culture. 3. In their rich variety and diversity, and in the reciprocal influences they exert on one another, all cultures form part of the common heritage belonging to all mankind.[66]

One contributor to UNESCO, in defining “cultural rights” in 1970, noted that “[t]here can be no doubt that the most strenuous efforts must be made to protect the cultural rights (the absolute freedom of expression) of the individual, who is the basic cultural unit.”[67] It is difficult to see how an entity (the State’s government) can assert a superior ownership claim to both human and community rights to cultural property. [68]

How do we reconcile the human right to “rights in property” with the enforcement of State ownership of all cultural property in Egypt, and where the very nature of state ownership deprives dispossessed minority religious communities and individuals of not only their own property, but also their “cultural right” to access such property? The countless human rights violations in Egypt and in other nations that have been granted import restrictions, despite the flagrant abuse of human and community and religious rights, historically and today should cause CPAC to reconsider whether renewing an MOU that would restitute State-appropriated objects to persecuting States is the right thing to do.

Conclusion

Import restrictions under the CPIA have provided for near permanent bans on the import of virtually all cultural items from the prehistoric to the present time from the countries which have sought agreements. If CPAC fails to heed the concerns of Congress regarding overbroad import restrictions unsubstantiated by clear evidence of meeting the four determinations, CPAC acts in derogation of U.S. law.

In considering the request for renewal of the MOU with the Arab Republic of Egypt, CPAC should be mindful of the primary determinations required for renewal. Congress placed procedural and substantive constraints on the executive authority to impose import controls under the CPIA and consideration of all these criteria is mandated at interim review and for proposed renewals. Restrictions may only be applied to archaeological artifacts of “cultural significance” “first discovered within” and “subject to the export control” of the requesting nation.[69] There must be some finding that the cultural patrimony of the requesting nation is in jeopardy.[70] The imposition of import restrictions must be part of a “concerted international response” “of similar restrictions” of other market nations, and can only be applied after less onerous “self-help” measures are tried.[71]

It is up to CPAC to read the law and to find the plain meaning in each one of these terms: “cultural significance,” “first discovered within,” “subject to the export control,” “self-help,” and “remedies no less drastic… are not available” are all key concepts that must be examined under each proposed MOU. Most important of all, import restrictions must also be consistent with “the general interest of the international community in the interchange of cultural property among nations for scientific, cultural, and educational purposes.”[72] This requirement has been so eviscerated – often relegated to a discussion of, “Were there any museum loans?” that CPAC seems to have forgotten it is even there.

In the case of the Egyptian renewal, it is time to look again at the requirements under the law. If the MOU is renewed, then it should be made subject to Egypt’s taking important steps to preserve its heritage to:

- Ensure adequate site protection by guards and enforcement of prohibitions on building and dumping at the sites.

- Require all archaeological projects to pay a living wage to excavators, security staff and local employees, establishing training programs and continuing site management plans to make cultural value equal economic benefit for locals.

- Complete a comprehensive digitalization of all objects held in excavation storerooms and museum storage for a national register of Egyptian heritage.

- Establish a transparent system of reasonable rewards for persons who find and report ancient objects located by accident, during farming or construction activities.

- Make public education on the benefits of preservation of heritage a priority, including it as part of the curriculum from childhood.

However, based upon the continuing neglect of these important aspects of the protection of its cultural heritage by the Egyptian government after the signing of the first MOU, the Committee for Cultural Policy and Global Heritage Alliance respectfully request that Egypt’s request for import restrictions be rejected.

Kate Fitz Gibbon

Executive Director, Committee for Cultural Policy, Inc.

Link to 2021-03-03 Exhibits for CPAC Testimony on Egypt Request.

[1] See “Statement of the Association of Art Museum Directors Opposing any Bilateral Agreement Between the United States and the Arab Republic of Egypt,” Association of Art Museum Directors, 2 June 2014, https://aamd.org/sites/default/files/key-issue/FINAL%20AAMD%20comments%202014.pdf

[2] Memorandum of Understanding Between the Government of the United States of American and the Government of the Arab Republic of Egypt Concerning the Imposition of Import Restrictions on Categories of Archaeological Material of the Arab Republic of Egypt, Nov. 30, 2016.

[3] “Egypt”, Human Rights Watch, https://www.hrw.org/middle-east/n-africa/egypt.

[4] Regeni’s body was found on February 3, 2016 in a ditch outside Cairo. It showed signs of extreme torture from beatings, including brain hemorrhage, two dozen bone fractures including all fingers, toes, legs, arms and shoulder blades, stab wounds, burns, slashings with razor blades, and punctures with an awl. A false trail was created by Egyptian police who alleged he had been killed by gang members, all of whom were then shot by police. Four Egyptian official were named by Italian prosecutors in 2020 as directly involved in his kidnapping and death. See “Italy charges Egyptian security agency officials over murder of Giulio Regeni.” https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/dec/10/italy-charges-four-egyptians-over-of-giulio-regeni. Before Cambridge, Regeni attended UWC-USA, an international baccalaureate school outside Santa Fe, New Mexico.

[5] According to the NY Times, “Numerous Egyptians have been jailed for posts on Twitter and Facebook deemed critical of the government, or of President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, and at least five hundred news websites have been blocked.” “Egypt Sentences Women to 2 Years in Prison for TikTok Videos,” https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/28/world/middleeast/egypt-women-tiktok-prison.html

[6] The most recent U.S. Government Country Report on Human Rights Practices 2019 states, “The significant human rights issues included: unlawful or arbitrary killings, including extrajudicial killings by the government or its agents and terrorist groups; forced disappearance; torture; arbitrary detention; harsh and life-threatening prison conditions; political prisoners; arbitrary or unlawful interference with privacy; the worst forms of restrictions on free expression, the press, and the internet, including arrests or prosecutions against journalists, censorship, site blocking, and the existence of unenforced criminal libel; substantial interference with the rights of peaceful assembly and freedom of association, such as overly restrictive laws governing civil society organizations; restrictions on political participation; violence involving religious minorities; violence targeting lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) persons; use of the law to arbitrarily arrest and prosecute LGBTI persons; and forced or compulsory child labor.” https://www.justice.gov/eoir/page/file/1258346/download

The United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner has published over 200 recommendations from member nations regarding Egypt’s arbitrary arrest and detentions, disappearances, torture and cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment of prisoners and detainees, extrajudicial, summary and arbitrary judicial executions, lack of freedom of expression, failure to administer justice and fair trials, and suppression of social, religious, and cultural rights. https://uhri.ohchr.org/en/search-human-rights-recommendations, last visited 2021-02-20. In 2020, Freedom House ranked Egypt as “Not Free” in its annual Freedom in the World report. It gave Egypt a “Political Rights” score of 7/40 and a “Civil Liberties” score of 14/60, with a total score of 21/100. The same year, Reporters Without Borders ranked Egypt at 166th place out of 180 countries, the 14th worst, in its Press Freedom Index. https://rsf.org/en/ranking

[7] Frederik Hagen and Kim Ryholt, The Antiquities Trade in Egypt 1880-1930, The H.O. Lange Papers, Scientia Danica. Series H, Humanistica, 4 · vol. 8, 2016.

[8] To give just one example, the collections made by George A. Reisner between 1899 and 1905 for Phoebe Hearst, now in the Hearst Museum of Anthropology at the University of California, Berkeley, amount to approximately 17,000 objects, forming the largest Predynastic era collection outside of Egypt. Phoebe Hearst’s Collections, Hearst Museum of Anthropology, Berkeley, CA, https://hearstmuseum.berkeley.edu/collection/phoebe-hearst-collections/

[9] Fairholt, Up the Nile and Home Again, 266-267, 1862, quoted in Frederik Hagen and Kim Ryholt, The Antiquities Trade in Egypt 1880-1930, The H.O. Lange Papers, 129, Scientia Danica. Series H, Humanistica, 4 · vol. 8, 2016.

[10] Frederik Hagen and Kim Ryholt, The Antiquities Trade in Egypt 1880-1930, The H.O. Lange Papers, 129, Scientia Danica. Series H, Humanistica, 4 · vol. 8, 2016.

[11] Id.

[12] Frederik Hagen and Kim Ryholt, The Antiquities Trade in Egypt 1880-1930, The H.O. Lange Papers, 129, Scientia Danica. Series H, Humanistica, 4 · vol. 8, 2016.

[13] The Wiliam Randolph Hearst Collection , Photographs and Acquisition Records on Microfiche, The Library of the C. W. Post Campus of Long Island University, Clearwater Publishing Co., NY.

[14] Al-Masry Al-Youm, “Retrieving artifacts from abroad not in Egypt’s favor: former minister,” Egypt Independent, 2 March 2017, https://www.egyptindependent.com/retrieving-artifacts-abroad-not-egypt-s-favor-former-minister/

[15] Adel Dargali, “Zahi Hawass: Egypt has much better museums than Europe and America,” El Watan News, 15 November 2015, https://www.elwatannews.com/news/details/1595058

[16] To give an example, just days before the opening of The European Fine Arts Fair (TEFAF) in New York in October 2018, the Consulate General of the Arab Republic of Egypt in New York sent a letter to fair administrators demanding that the consulate be given photographs and documents of all Egyptian items sold there in order to ensure that the items were legally owned and exported. In justification, the consulate stated that unnamed exhibitors at the fair had previously exhibited looted Egyptian antiquities and asserting “that [a] number of those antiquities, illegally possessed by ***REDACTED***, have been repatriated to Egypt.” The letter was cc’d to Manhattan Assistant District Attorney Matthew Bogdanos. However, the Egyptian export licenses the Consulate said should be shown as proof of legal export are usually summaries of large lots and fail to itemize or describe items. In the end, there were no seizures, attempted seizures, or claims raised about any Egyptian antiquities at the fair.

[17] Forming Material Egypt: Proceedings of the International Conference, London, 20-21 May, 2013, Patrizia Piacentini, “The antiquities path: from the Sale Room of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, through dealers, to private and public collections. A work in progress.” EDAL IV, 2013/2014, p 117-118. Citing to F.Ll. Griffith, Progress of Egyptology, in Id. (ed.), Egypt Exploration Fund. Archaeological Report 1902-1903, London [1903], p. 12.

[18] Egyptian Law on the Protection of Antiquities, Law No. 117, art. 6 (1983).

[19] Id.

[20] However, the definition of “antiquity” also includes more recent objects that fit these categories even if it does not fall within that time frame, “where the Prime Minister so decides.” Id. at art. 1.; art. 2.

[21] Marina Gamil, New law increases penalties for antiquity-related crimes, Egypt Today, 24 April 2018, https://www.egypttoday.com/Article/1/48513/New-law-intensifies-penalties-for-antiquity-related-crimes

[22] Mussa Youssef and Muhammad Ibrahim, “From “Zamalek apartment” to the heart of Europe…The Smuggling of Pharoanic Antiquities,” Daraj, 27 February 2021, https://daraj.com/en/43010/

[23] Marina Gamil, “New law intensifies penalties for antiquity related crimes,” Egypt Today, 24 April 2018, https://www.egypttoday.com/Article/1/48513/New-law-intensifies-penalties-for-antiquity-related-crimes

[24] Ladislav Otakar Skakal, a former Italian honorary consul in Luxor was sentenced in absentia to a fifteen-year jail sentence in Egypt on January 2020 for smuggling antiquities. The crime was not discovered in Egypt; Italian authorities became suspicious after a container was left on the dock in the Italian port for three months. According to Egyptian authorities, Skakal’s diplomatic status enabled him to ship the items out of Egypt without a customs inspection, although Skakal’s diplomatic status actually was withdrawn in 2015 after he left his post. He was said to have been working with Egyptian accomplices who supplied the antiquities to him. In 2017 Italian police found what Egyptian officials described as 21,660 coins of all periods, 151 Shabti statues, eleven pottery utensils, five mummy masks – and a wooden sarcophagus inside boxes said to be household goods of the consul. Egyptian authorities arrested the owner of the shipping company, Medhat Michel Girgis Salib. Also arrested was Raouf Boutros Ghali, the nephew of former U.N. Secretary-General, the late Boutros Boutros-Ghali, and brother of Youssef Botros Ghali, Egypt’s former Minister of Finance from 2004-2011 under President Hosni Mubarak. Raouf Boutros Ghali was convicted in a Cairo court in February 2020 for his involvement in the operation, sentenced to thirty years in prison and fined 6 million Egyptian pounds (~$382,000). Id.

[25] Walt Curnow, “Real-life tomb raiders: Egypt’s $US3 billion smuggling problem,” ABC News Australia, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-10-21/egypts-3-billion-dollar-smuggling-problem/10388394

[26] Egypt faces increased home illegal digging for antiquities amid COVID-19 pandemic.”, http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2020-12/28/c_139622582.htm

[27] The Management of Egypt’s Cultural Heritage, Vol. 2. (pp.14-47) Editors: F. A. Hassan, G. J. Tassie, L. S. Owens, A De Trafford, J. van Wetering, O. El Daly, January 2015, Golden house Publications and ECHO, p 21

[28] Khalid Hassan, “Egypt takes stock of neglected antiquities,”https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2017/07/egypt-antiquities-campaign-prevent-theft.html

[29] Id.

[30] The 2020 Cultural Perceptions Index ranks Egypt as 117th out of 180 countries worldwide, with a score of only 33 out of 100. The Cultural Perceptions Index is not able to maintain a national chapter in Egypt, whose government is hostile to NGOs concerned with corruption and human rights violations. https://www.transparency.org/en/countries/egypt, last visited 2021/02/20.

[31] See Alex Capon, “British Museum unveils antiquities database but dealers raise concerns,” Antiques Trade Gazette, 20 April, 2020,

https://www.antiquestradegazette.com/print-edition/2020/april/2439/news/british-museum-unveils-antiquities-database-but-dealers-raise-concerns/. See also “Egypt Rejects Accessible Database of Art in Circulation.” Cultural Property News, March 12, 2019, https://culturalpropertynews.org/egypt-rejects-accessible-database-of-art-in-circulation/. The project also brings trainees in provenance documentation from Egypt to the British Museum, and provides on-site training in Egypt and Sudan to antiquities staff from Egypt’s Ministry of Antiquities in Egypt and Sudan’s National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums (NCAM).

[32] Antiquities Dealers Association, https://theada.co.uk/

[33] International Association of Dealers in Ancient Art, https://iadaa.org/

[34] Al-Masri Al-Youm, “Japan contributed to 75% of Grand Egyptian Museum’s cost: minister,” Egypt Independent, October 31, 2017, https://egyptindependent.com/japan-contributed-75-grand-egyptian-museums-cost-minister/.

[35] Although the Egyptian army swept successfully into the Sinai Peninsula in the October 6, 1973 surprise attack that began the Six Day War, Egypt did not gain back territory, but lost both the 23,500-square-mile Sinai Peninsula and the Gaza Strip. The war ended with Israel’s rout of Egypt and Syria and their Iraqi and Jordanian allies.

[36] Al-Masri Al-Youm, “Egypt’s Antiquities Ministry to open 3 museums at LE725 million,” Egypt Independent, https://egyptindependent.com/egypts-antiquities-ministry-to-open-3-museums-at-le725-million/

[37] Lynn Neary, “Paying for the King Tut Exhibit,” NPR, 16 June 2005, https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=4705671

[38] Thomas Dowson, “Tutankhamum Treasures of the Golden Pharaoh 2019-2023,” Archaeology Travel, https://archaeology-travel.com/exhibitions/tutankhamun-treasures-of-the-golden-pharaoh/

[39] Martin’s recording, which hit #17 in the charts, featured the lyrics, “Now, if I’d known, They’d line up just to see you, I’d trade in all my money, And bought me a museum – King Tut.” Songfacts, https://www.songfacts.com/lyrics/steve-martin/king-tut. See also, https://youtu.be/FYbavuReVF4

[40] Sarah Buder, “A Rare Exhibition of Egyptian Treasures Will Debut in the US this Year,” 3 February 2021, AFAR, https://www.afar.com/magazine/massive-exhibition-of-egyptian-gold-treasures-to-debut-in-2021.

[41] Letter to Secretary of State Mike Pompeo Regarding Cultural Property Agreements, JIMENA, 12/9/2018, https://www.jimena.org/letter-to-secretary-of-state-mike-pompeo-regarding-cultural-property-agreements/

[42] Id.

[43] With the establishment of Israel, in 1948, the Egyptian government began enforcing aggressive and repressive measures against Jews. During the Suez crisis, Egypt’s government declared all Jews enemies of the state. In the aftermath, some 25,000 Jews fled Egypt. After the Six Day War, when many Egyptian Jews were imprisoned and tortured, only 2500 Jews remained in Egypt. Throughout these expulsions, the Egyptian government seized Jewish businesses and personal property. In 1971 it was estimated that Jews lost $500 million in personal property, $300 million in communal religious property, and $200 million in religious artifacts. Today, only five Jews, all of them older women, are estimated to remain. Source JIMENA, http://jimenaexperience.org/egypt/about/past-and-present/.

[44] 81 Fed. Reg at 87,809, sec. X. “Coptic Paintings” and mosaics that contain “religious images and scenes of Biblical events” are also prohibited from U.S. import. Sec. XI (F); Sec. XII.

[45] Id. at XIII.

[46] Id.

[47] “According to a local Jewish nongovernmental organization (NGO), there are six to 10 Jews [in Egypt].” International Religious Freedom Report for 2019, United States Department of State, Office of International Religious Freedom, p. 3.

[48] Kate Fitz Gibbon, Now That Jews are Gone, Egypt Says it will Restore Sites, Cultural Property News, May 27, 2017, https://culturalpropertynews.org/now-that-jews-are-gone-egypt-says-it-will-restore-sites/

[49] Samir Samir, “Jews of Egyptian descent petition Sisi to digitize records”, Cairo Post, 2/21/2016, https://nsnbc. me/2016/02/21/jews-of-egyptian-descent-petition-sisi-to-digitize-identity-records/

[50] 124 News, “Egypt’s Jewish Literary Heritage in danger of being forgotten,” 12/20/2015, https://www.i24news. tv/en/news/international/middle-east/97298-151229-egypt-s-jewish-literary-heritage-in-danger-of-being-forgotten. When asked about the books in the Jewish Library’s future, Mohamed Abdel-Latif, head of Islamic, Coptic and Jewish Antiquities Section of the Ministry of Antiquities, said that “The body authorized to be responsible for Jewish books and manuscripts is the Ministry of Culture.” Culture minister, Helmy al-Namnam then stated that “there is nothing called ‘Jewish books in Egypt,’ the books scientifically should be classified as Arabic, Persian, Turkish, etc.”

[51] Al-Masri Al-Youm, “25% of restoration of Alexandria Eliyahu Hanavi Synagogue completed,” Egypt Independent, 2/10/2018, http://www.egyptindependent.com/25-of-restoration-of-alexandria-eliyahu-hanavi-synagogue-completed/

[52] Jacob Wirtschafter, “Egypt plans to restore Alexandria synagogue in bid to promote diversity”, USA Today, 7/27/2017, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2017/07/27/egypt-plans-restore-alexandria-synagogue-bidpromote-diversity/517356001/. The efforts were speculated to be part of Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi’s attempts to ameliorate and promote the public understanding of “diversity” after a series of bombings in minority communities carried out by the Islamic State.

[53] Sarah El-Deeb, “Egyptian Jewish Leader buried in cemetery she tried to restore,” 4/19/2013, Times of Israel, https://www.timesofisrael.com/egyptian-jewish-leader-buried-in-cemetery-she-tirelessly-tried-to-restore/

[54] U.S.-Funded Conservation Project at Bassatine Cemetery Highlights Egypt’s Diverse Cultural Heritage” U.S. Department of State, 23 January 2020,“As part of the longstanding strategic partnership between the United States and Egypt, since 2001 the American people have funded the conservation and restoration of over a dozen Egyptian cultural heritage sites under the AFCP.” https://eg.usembassy.gov/bassatine-cemetery/

[55] Jenna Johnson, “In Cairo, Pence praises the friendship and partnership between the U.S. and Egypt,” Washington Post, 1/20/2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/post-politics/wp/2018/01/20/in-cairo-pence-praises-the-friendship-and-partnership-between-the-u-s-and-egypt/

[56] The Looting in Egypt has Increased, ECHO, 3/18/2011, http://www.e-c-h-o.org/news/increasedlooting.htm

[57] Kate Fitz Gibbon with Elizabeth Bolman, “Elizabeth Bolman Interview: The Red Monastery Church,” Cultural Property News, 22 February 2020, https://culturalpropertynews.org/elizabeth-s-bolman-interview-the-red-monastery-church/.

[58] Emmanuel Parisse, “Egypt’s last Jews aim to keep heritage alive,” The Times of Israel, Mar. 26, 2017, https://www. timesofisrael.com/egypts-last-jews-aim-to-keep-alive-heritage/

[59] 81 Fed. Reg at 87,809, sec. X. “Coptic Paintings” and mosaics that contain “religious images and scenes of Biblical events” are also protected. Sec. XI (F); Sec. XII.

[60] Id. at Art. II (3).

[61] See e.g. Executive Order 13350 (2005); Import Restrictions Imposed on Archaeological and Ethnological Material of Iraq, 73 FR 23,334 (Apr. 30, 2008) (19 C.F.R. 12)

[62] 19 U.S.C. § 2602(a)(1)(D).

[63] Kimberly L. Alderman, The Human Right to Cultural Property, 20 Mich. State Int’l L. Rev. 69, 74 (2011).

[64] Erik Jayme, Human Rights and Restitution of Nazi-Confiscated Artworks from Public Museums: The Altmann Case as a model for Uniform Rules?, Kunstrechtsspiegel 49 (2007) https://journals.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/index.php/

[65] Universal Declaration of Human Rights, art. 22 (1948).

[66] Declaration of Principles of International Cultural Co-operation, art. 1, Nov. 4, 1966

[67] Breten Breytenbach, Cultural interaction, UNESCO Definition of Cultural Rights at 40.

[68] Yehudi A. Cohen, From Nation State to International Community, UNESCO (1970) at 77; 79. http://unesdoc.unesco. org/images/0000/000011/001194eo.pdf . Cohen does argue that strengthening national regimes, will ultimately assure securing of individual rights.

[69] 19 U.S.C § 2601

[70] Id. § 2602.

[71] Id.

[72] Id.

Site of the excavation of Heliopolis, 2015. The German expedition, upon their return after a year, found their excavation partly covered by a garbage dump, requiring them to start each morning by shoveling the trash out of the excavation. In 2016, an illegal concrete construction was found on the spot where they had begun excavating a temple the prior season. Courtesy of the Egyptian Museum Georg Steindorff, University of Leipzig, Germany.

Site of the excavation of Heliopolis, 2015. The German expedition, upon their return after a year, found their excavation partly covered by a garbage dump, requiring them to start each morning by shoveling the trash out of the excavation. In 2016, an illegal concrete construction was found on the spot where they had begun excavating a temple the prior season. Courtesy of the Egyptian Museum Georg Steindorff, University of Leipzig, Germany.