The art world is dominated today by stories about spectacular multi-million dollar sales of contemporary artworks at shows and auction houses. Yet the market for ancient and ethnographic artworks has no such lofty expectations. There are far fewer important ancient artworks offered at auction in the US than just a decade ago, and there are fewer foreign exhibitors (or even American galleries) willing to show at major antique fairs in New York.

US authorities’ aggressive seizures of artworks from long-held collections and the unprecedented number of prosecutions based upon foreign laws that nationalize virtually all antique artworks have made art dealers, collectors, and museums hyper-cautious. These enforcement actions threaten to end the once-dominant New York market in global antique and tribal art.

Paul Mellon and National Gallery director John Walker examine paintings to be installed in a 1967 exhibition. National Gallery, Washington, DC.

In any case, when prosecutors describe acquisitions made 50 years or more ago as “criminal,” caution and due diligence may not be enough. Why take the chance of importing art when you do not know if it will be seized based on secret information, or on a foreign law never before enforced in the US (or for that matter, not enforced by the foreign country itself)?

Background

Americans have been collecting foreign art and artifacts since this nation was founded. The great US museum collections began through massive, almost royal donations by magnates such as Andrew Mellon and J. Pierpont Morgan, but over time, it has been gifts from tens of thousands of smaller donors that brought the vast majority of the artworks to US museum collections.

Museums have benefited hugely through the far wider scope and diversity of gifts from collections built in the 1960s-1990s. African, Asian, and South American artworks flowed into museums that served an increasingly diverse American public. This was one of the most enthusiastic, wide-ranging, and eclectic periods for collecting global art in history – inspired in part by the awakening interest in foreign philosophy, spirituality, and culture among the post-war Peace Corps and hippie generation.

Press photo of The Beatles during Magical Mystery Tour, By Parlophone Music Sweden [CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

It is no coincidence that archaeologists and anthropologists of the same generation were the first to argue against the pillaging of art-source nations for the Western market. Nor, sadly, is it surprising that their pleas for archeological protection were quickly co-opted by political leaders in those same source countries. Today, nationalist claims for exclusive control over ancient heritage trump international concerns for a humanist approach to history or archaeological interests. In no small part, this radical policy change is due to the work of a dedicated coterie of foreign service officers that built a virtually autonomous mini-agency at the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs within the Department of State. There, the DOS’s Cultural Heritage Center dispenses grants to academics, exchanges personnel with archaeological groups and university departments, and directly coordinates with US Customs and prosecutors.

Most importantly, by tightly controlling the membership, public access and even the information supplied to Presidential appointees at the Cultural Policy Advisory Committee, the Cultural Heritage Center has forwarded an exclusively state-centric, foreign-nationalist cultural policy agenda for the US. For the last twenty years, it has encouraged foreign states to seek import restrictions for cultural goods into the US, regardless of merit and often in defiance of the requirements set by Congress, closing off access to entire areas of the world to US art collectors and museums.

Today, art agreements that benefit foreign governments are the rule, and it appears to make no difference to US policymakers if authoritarian rulers in China, Cambodia, or Egypt exploit their authority over culture to abuse human rights or harm cultural minorities.

Through the Cultural Property Advisory Committee (known as CPAC), the US government supports an anti-internationalist perspective on art collecting that not only blocks imports, but whose influences extend even into academe. At its most extreme, this anti-collecting perspective not only inhibits exhibition of artworks – it curtails the art-historical dialog by making art without a proper archaeological pedigree unpublishable – treated as if it did not exist.

The 1970 Fallacy and Art “Orphans”

The 1970 adoption date of the UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property is now assumed to have given notice of an international policy change and created red line between lawful and unlawful objects. (Never mind that the Convention’s passage rated just a few paragraphs in the NY Times when it was signed in 1970, and received little other notice for several decades. Prior to passage, the Times did cover US opposition to elements of the pending 1970 agreement in an article on Turkish officials’ demand for return of objects from US museums.) Objects that can be proven to have been collected before 1970 are categorized as “good” for marketing, collecting and museum acquisition purposes. Objects without proof of collection date or collected post-1970 are “bad.”

In fact, a pre- or post-1970 acquisition date has no legal effect on title or ownership. Nor do art source countries limit their claims to objects exported after 1970; Turkey refuses to acknowledge Ottoman period partage agreements that divided archaeological finds between local and foreign archaeologists. Greece says the Ottomans had no right to hand over the Parthenon marbles to France and England in 1801 because to them, the Ottomans who held Greece for 250 years were an occupying power.

Orpheus and two Sirens. J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu, California, USA. I, Sailko [GFDL CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons.

Museums were faced with accusations of buying from looters. The museums needed to establish consistent due diligence standards, and the AAMD adopted a threshold year, refusing to accept international objects acquired after a certain date. Unfortunately, the AAMD chose to use a 1970 date – long before there was general awareness among collectors or art dealers of the harms caused by archaeological looting and well before US Customs began to ask for any kind of permits for importation.

In consequence, potential donors or sellers must now provide museums with proof of legal import/export from almost 50 years before, when no US customs law ever required keeping, or even having such records in the first place. (Even now, despite provisions included in US-foreign cultural agreements asking foreign nations to create lawful systems for export, none have done so in response.)

The AAMD decision cut off acquisitions and gifts of international objects at the very point that the international collecting revival began in the early 1970s. It also turned hundreds of thousands of legally owned artworks in private collections into “orphan objects” that, because of their unrecorded provenances, cannot be donated to US museums.

History of CPIA and CPAC

However, the 1970 rule is a self-imposed injury done by museums to museums. It did not create a complete barrier blocking museum and public access to art. The primary laws that have done so are the 1983 Cultural Property Implementation Act (CPIA), 19 U.S.C. §2601 and the 1934 Stolen Property Act (to be covered in the August 2018 Newsletter). Both laws have been around for a long time, and both have impacted US cultural policy in ways never intended by the legislators who wrote them.

United States Department of State headquarters at 2201 C Street, NW in Washington, D.C. By AgnosticPreachersKid at English Wikipedia [CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Mark B. Feldman, who was the primary State Department negotiator on both the CPIA and on treaties with Mexico, has said,

“there have been dramatic changes in U.S. law and practice that have established a very different policy balance than the one the State Department negotiated in the UNESCO Convention and that Congress approved in the implementing legislation.”

When Congress passed the CPIA in 1983, the law established criteria for agreements that would result in selective import controls, rather than an across-the-board import ban on illegally exported material. It also placed supervision of CPAC with the US Information Agency instead of the Department of State, attempting to keep the CPIA from being used as a diplomatic band-aid or risking US access to art being negotiated away in exchange for more pressing US diplomatic, economic, and security interests.

The CPIA authorized seizure and forfeiture of certain designated objects that are illegally imported. It not only implemented Article 9 of the 1970 UNESCO Convention, permitting the bilateral import restriction agreements to protect objects in “jeopardy,” it also made Article 7(b) into US law, so that any object taken unlawfully from a foreign museum, church or any other public institution or private collection is treated as stolen under US law as well.

For the most part, stakeholders in either government or the arts agreed that this was an appropriate balance that would protect archaeological sites, ensure that stolen items did not enter the US, and thus enable a continuing circulation of art in a lawful market for the benefit of US museums and the public.

Speaking of the limits imposed by Congress, Feldman continued:

“Ultimately, most stakeholders agreed that carefully focused import controls were necessary to dampen market incentives for pillage of archeological sites and endorsed an international convention for that purpose provided it had no retroactive effect on existing American collections. The panel rejected the “blank-check” approach that would have implemented foreign export controls designed to keep art at home in favor of targeted import controls intended to discourage looting that threatened to destroy the record of human civilization while preserving imports of ancient art to promote study of ancient civilizations.”

The limited import restrictions imposed under early agreements have long since expanded into blanket blockades covering virtually every object from ancient civilization through colonial periods and beyond.

State Department announcement of Celebration of Italian MOU.

States Feldman:

“In recent years, the State Department has implemented the program vigorously believing strongly in its mission to help protect the cultural heritage of mankind and responding to the demands of foreign states. This is commendable provided the Department complies with its statutory mandate. The Executive is not authorized to establish import controls without international cooperation unless an emergency condition exists as defined by law, and Congress did not intend to authorize comprehensive import controls on all archeological objects exported from a country of origin without its permission. The purpose of the program is not to keep art at home, but to help protect archeological resources from pillage; the findings required by the CCPIA were established for that purpose.”

The moderate policies of the 1980s have been abandoned and the State Department now “celebrates” every all-encompassing agreement as a positive achievement, instead of a regrettable but necessary step to assist nations that cannot help themselves to protect threatened archaeological sites.

What is Cultural Property?

The CPIA’s Section 2601 uses a general definition in Article 1 of the Article 1 of the 1970 UNESCO Convention to define what is “cultural property.” It is “property which, on religious or secular grounds, is specifically designated by each State as being of importance for archaeology, prehistory, history, literature, art or science.”

This UNESCO definition includes, but is not limited to:

specimens of fauna, flora, minerals and anatomy, and objects of paleontological interest, property relating to social, political, science and technology and military history, products of archaeological excavations (including regular and clandestine), elements of artistic or historical monuments or archaeological sites, antiquities more than one hundred years old, such as inscriptions, coins and seals, objects of ethnological interest, pictures, paintings and drawings, original works of statuary art and sculpture, engravings, prints and lithographs, rare manuscripts and incunabula, old books, documents and publications of special interest (historical, artistic, scientific, literary, etc.), postage, revenue and similar stamps, archives, including sound, photographic and cinematographic archives, articles of furniture more than one hundred years old and old musical instruments.

This all-inclusive definition of “cultural property” is clearly not limited to items of “cultural significance” in the statute[1], and as Congress set forth in its 1982 Senate Report[2]. [3]

Signing of a Memorandum of Understanding between the United States and the Government of Libya. Department of State.

What Criteria Must Be Met Under the Law for an Agreement Under the CPIA?

To impose import restrictions, the CPAC must determine whether the request satisfies all four requirements set forth in the statute. The requirements are:

- The cultural patrimony of the State Party is in jeopardy from the pillage of archaeological or ethnological materials of the State Party.

- The State Party has taken measures to protect its cultural patrimony.

- The application of the requested import restriction if applied in concert with similar restrictions implemented, or to be implemented within a reasonable period of time, by nations with a significant import trade in the designated objects, would be of substantial benefit in deterring a serious situation of pillage, and other remedies are not available.

- The application of the import restrictions is consistent with the general interest of the international community in the interchange of cultural property among nations for scientific, cultural, and educational purposes.

For almost 20 years, critics of the operation of CPAC by the Department of State (including a number of former members of CPAC) have argued that the MOUs entered into by the United States have blatantly disregarded the requirements of the law.

James Fitzpatrick is an attorney who was personally involved in the negotiations surrounding passage of the CPIA in 1983 and in frequently giving testimony on proposed agreements under it with foreign nations on behalf of ancient art dealers. According to Fitzpatrick, since the transfer of the CPIA’s administration to the US Department of State in 1999, the State Department’s decisions have been:

- Essentially to read the “concerted international agreement” requirement out of the Act;

- To promulgate across-the-board embargos extending to a nation’s entire cultural history, or thousands of years of it;

- To disregard the requirement that a U.S. embargo would be efficacious by permitting a requesting nation to sell in its markets the very items it wants to deny to the U.S. market;

- Conducted all its proceeding in the tightest grip of secrecy, denying the public the opportunity to evaluate its activities;

- Permitting the MOU process to become a diplomatic bargaining chip instead of making decisions based on the cultural criteria contained in the Act.[4]

Objects seized from Iraq, and returned in a special ceremony to the Iraqi nation by ICE.

Too Broad Categories and No ‘Concerted International Response’

Particularly galling to Fitzpatrick was the fact that the ‘multinational response’ requirement was key to enabling the CPIA’s final compromise in Congress in 1983. The fact that the US would not act alone in placing import restrictions on foreign objects, simply pushing objects to other markets, but rather that other major market nations would join the US to ensure import restrictions was what enabled passage of the CPIA in the first place.

“The concept that U.S. import controls should be part of a concerted international effort is embodied in article 9 of the Convention and carried forward in section [2602 of the 1983 Act]. In previous years’ consideration of various proposals for implementing legislation, a particularly nettlesome issue was how to formulate standards establishing that U.S. controls would not be administered unilaterally. The Committee believes that the language now adopted…and which is agreeable to all private sector parties that have contributed actively to the Committee’s consideration of the bill, satisfies the twin interests of obtaining international cooperation while achieving the goal of substantially contributing to the protection of cultural property from further destruction.” (emphasis added) See S. Rep. No. 564, 97th Cong., 2nd Sess. at 6 (1982)[5]

Fitzpatrick notes,

“Section 2602(2)(c) explicitly denies the President the authority to enter into an import limitation unless there is a concerted international response to the particular problem of pillage identified by a requestor nation…Significantly, under Section 2602(d), the President shall suspend our MOU if other art importing countries have not implemented “import restrictions” that are similar to our import restrictions.”[6]

The State Department has not only failed to require any proof that objects are under threat, but instead has routinely executed blanket agreements that extend to a nation’s entire cultural history.[7] Says Fitzpatrick, “Not only was the scope of the Act meant to be narrow, it was never contemplated that the President’s authority would extend to restricting the import of the entire cultural patrimony of a country.”

He goes on,

“on their face, wall-to-wall embargoes fly in the face of Congress’ intent. Congress spoke of archeological objects as limited to “a narrow range of objects…” [Sen. Report, p. 4.] Import controls would be applied to “objects of significantly rare archeological stature…” [Ibid.] As for ethnological objects, the Senate Committee said it did not intend import controls to extend to trinkets or to other objects that are common or repetitive or essentially alike in material, design, color or other outstanding characteristics with other objects of the same type….”[Id. at 5]

Since Fitzpatrick’s 2010 statement, not only has the State Department ignored the requirement that “archaeological or ethnological material” be of cultural significance, it has stretched the bounds of reason to prohibit importation of colonial-period Catholic religious paintings and sculpture and Ottoman period Jewish religious artifacts[8] in agreements on the basis that they fit Congress’ description of “products of a tribal or non-industrial society.”[9]

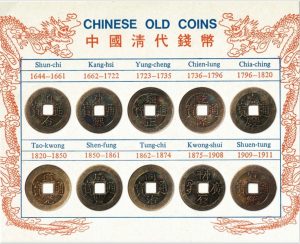

Chinese coin sampler.

Items Restricted from US Import Are Sold Openly in Source Countries

Numerous commentators have noted that the State Department does not require a requesting country to remove those artworks from requests for embargo that are sold in open, domestic trade. Probably the most egregious example of this is the US-China Memorandum of Understanding (MOU), forbidding entry of Chinese art up through the Tang Dynasty in the US. China is the world’s largest market for antique and ancient art from China, and approximately 100 new museums were opened in China during the 2016 year alone. Yet the MOU denies US citizens access to the same items China allows its own citizens to buy. Other major market nations: Hong Kong,[10] Japan, Singapore, Taiwan, and Great Britain, also have no import restrictions against traded Chinese art.

Granting National Ownership Claims to Dictatorial Regimes Rather than Oppressed and Exiled Minorities

The claims of religious and cultural minorities to objects from their own heritage are disregarded in US cultural property agreements, not only when governments are actively engaged in destroying the minority culture (such as China is in its Tibetan and Uyghur regions) but also when the minorities have been driven out of their homes and country, and forced to leave their possessions behind, as in the case of minority populations in the Middle East.

Through inclusion of Torahs, icons, religious books and ritual objects on Designated Lists, the State Department has recognized the authority of oppressive nationalist regimes in the Middle East over Jewish and Christian artifacts. Jewish and other minority peoples have been driven out of Syria, Libya, Iraq, and Egypt – regions where they lived for thousands of years, but objects belonging to their cultural heritage are now claimed as property of those states.

HSI special agents display an artifact at a Mexican repatriation ceremony. https://www.ice.gov/history

No Entry of Art from Major World Cultures to the US

Right now, there are 20 foreign countries whose art and artifacts are subject to comprehensive blockades against US entry. Belize , Bolivia , Bulgaria , Cambodia , China , Colombia , Cyprus , Egypt, El Salvador , Greece, Guatemala , Honduras , Italy , Libya, Mali , Nicaragua , and Peru have bilateral agreements that once implemented, have been renewed again and again every 5 years, so that some, such as El Salvador, have been in place for over 30 years. Iraq (2008) and Syria (2016) are currently subject to legislative “emergency actions.” (Mexico is covered in another longstanding treaty.)

Months after a CPAC review, the American public and US art dealers, auction houses, and museums learn what the import restrictions will be through publication in the Federal Register. The restrictions will be effective from that day of first publication for 5 years.[11] Based on the past record of the CPAC and its State Department administrators, the restrictions on artifacts from every country are likely to be extremely broad and renewed every five years through the foreseeable future.

US Customs Overreach

Goods entering the US on a Designated List after that day can be seized, and unless an importer can prove to US Homeland Security’s satisfaction (and there is nothing limiting HSI’s demands) that the items were out of the source country for 10 years or they were out of the originating country prior to the date of import restrictions, then they will be returned to the source country. US Customs (CBP) takes the position that the importer, not Customs, has the burden of showing that goods meet these restrictions, but that is not actually what the statue says – one reason for a pending case in the 4th Circuit.[12]

In theory, under the CPIA, importation of an object that can be proved to have been outside of the source country for at least ten years will not encourage looting in that type of object; it may therefore be lawfully imported into the U.S. Homeland Security and ICE policy is not lenient with regard to imports of ethnographic and ancient art, however, and complaints are frequent that the months and years it can take to resolve a forfeiture claim, the repeated requests for more documentation, and the cost of paying an attorney to deal with a forfeiture mean that almost all objects are abandoned at Customs, rather than fought for. They are then returned with much ceremony to source country embassies by ICE, as recovered “stolen” objects.

Delegation from the Peoples republic of China at the Cultural Heritage Center at the US Department of State. US Department of State.

Fundamental Bias at the State Department’s Cultural Heritage Center

CPAC has also been widely challenged as not operating in the public interest. The fundamental issue with the operation of CPAC is its pro-archaeological and anti-art trade bias and overt manipulation of the committee’s decision-making process by State Department staff. William G. Pearlstein sums up the situation in his thorough analysis of US cultural policy, White Paper: A Proposal to Reform U.S. Law and Policy Relating to the International Exchange of Cultural Property:

“Simply put, archeologists’ desire to use the CPIA as a vehicle to advance a statist model lacks any support in the terms of UNESCO, the CPIA, the Senate Report, the legislative history of CPIA, or the scholarship that underlies the CPIA. Their viewpoints are nevertheless allowed to dominate Committee deliberations because the State Department’s legal advisors to the CPAC have taken permissive internal interpretive positions in order to facilitate the grant of import restrictions.”[13]

Legal scholars Andrew L. Adler and Stephen Urice plainly describe the State Department’s bias toward import restrictions:

“Journalists and former members of CPAC have asserted that, not only has the State Department eliminated transparency, but it has also transformed CPAC into an institution engaged in the proactive pursuit of broad import restrictions. Indeed, one reporter has characterized CPAC’s staff as having “pursued a veritable — and intensifying — fatwa against the antiquities trade…[,] successfully hijack[ing] American foreign policy on cultural patrimony” by employing a number of aggressive tactics, such as: selectively controlling the information provided to members of CPAC; employing staff members with an archaeological background, who control CPAC’s mission and even prepare its reports; manipulating the CPAC nomination process; silencing the views of stakeholders (especially dealers); and unevenly applying conflict-of-interest rules. While the State Department is legally permitted to advise the President to reject CPAC’s recommendations, it has no legal authority to prevent CPAC from carrying out its mission in the manner prescribed by Congress.”[14]

CPAC Operates on Short Notice in Hyper-Secret Committee Meetings

Compared to these egregious abuses, the tactics used to limit public input seem petty, but should be mentioned. Several requests in 2017-2018, including a new MOU requested by Libya, gave only one week’s notice to provide written comment online. This unjustifiably limited time frame has resulted in the Association of Art Museum Directors refusing to respond, because there is insufficient time for the organization to reach out to its museum members for comment.

Jay Kislak, CPAC Chairman from 2003 to 2008, made a sworn Declaration supporting a claim that State Department staff had altered the committee’s recommendations and failed to notify Congress:

“During my tenure as Chairman of CPAC, I became concerned about the secretive operations of the Cultural Heritage Center and its lack of transparency in processing requests for import restrictions made on behalf of foreign states. I believe this lack of transparency has hampered the ability of museums, private parties and others to make useful presentations to CPAC. I also believe that this lack of transparency has also hampered the ability of CPAC to provide recommendations to the executive branch about the best way to balance efforts to control looting at archeological sites against the legitimate international exchange of cultural artifacts.”

“I believe that the release of details of foreign requests for import restrictions could promote transparency and allow CPAC to be better able to make recommendations. I also believe that the release of CPAC’s reports in full could also promote the same goals. I do not believe that release of this material after a decision has been made will discourage CPAC members from discussing the merits of each case. To the contrary, release of CPAC reports will allow interested parties to frame their arguments more effectively when import restrictions come up for renewal every five (5) years. In addition, release of this documentation will also promote the accountability of Cultural Heritage Center Staff to both CPAC and the public at large.”[15]

There is no legal requirement for the total secrecy of CPAC meetings, although classified information, if it was ever presented, could reasonably be restricted. Yet, CPAC members are warned never to make anything about the meetings public and told that punitive action will be taken if they do so.[16] Information can rarely be obtained about the country requests or the recommendations of the CPAC committee, even through Freedom of Information Act requests, which if they are answered at all, are highly redacted.

Former Chairman Kislak stated in a public program that, “[Maybe others] heard state secrets discussed. I never did. I never heard anything that was diplomatic material.”[17]

At the same panel, this author (also a former CPAC member) stated, “The argument that looters will use the Committee briefing materials to seek out sites is ridiculous. In one briefing report that we received, eighty percent of the items were things from eBay — showing there was a market.”[18]

The Composition of the CPAC and its Administration

Whether the current blockades are based upon emergency actions, agreements, or legislation with attached Designated Lists of objects subject to import restrictions, all have been colored by anti-art trade activism at the Cultural Heritage Center at the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs.

Implementing ever-broader import restrictions has been a consistent pattern since 2000, when oversight of the CPAC moved from USIA to the Department of State, and remained under the direction of the same individual, Maria Kouroupas, for 18 years.[19] Kouroupas retired in 2018, but her protégés remain, and not only at the Cultural Heritage Center. Some have played important roles in other federal agencies and in the White House, most notably in the person of Dr. Bonnie Magness-Gardiner, now semi-retired as Program Manager of the Art Theft Program (National Stolen Art File and Art Crime Team) at FBI headquarters in Washington, DC.

The failure to seat individuals representing the balanced range of interests Congress sought has been a major problem at CPAC since it came to the Department of State. By law, CPAC must consist of 11 experts appointed by the President: 2 members representing museum interests, 3 members expert in archaeology or ethnology, and 3 experts in the international sale of cultural property (understood to represent the interests of the art trade), and 3 members representing interests of the general public.

The current members of CPAC are:

- Chairman, Jeremy Sabloff, Museums Member, Anthropologist

- Lothar von Falkenhausen , Archaeology Member, Professor of Chinese Archaeology

- Rosemary Joyce, Archaeology Member, Professor of Anthropology

- Nancy Wilkie, Archaeology Member, Professor of Anthropology

- Karol Wight, Museums Member, President and Executive Director, Corning Museum of Glass

- James W. Willis, Art Trade Member, James Willis Tribal Art

- Dorit D. Straus , Art Trade Member, Art and Insurance Advisor, Visiting Lecturer at the Association for Research into Crimes Against Art

- John Frank , Art Trade Member, attorney at Microsoft, specialties security, software licensing, and copyright law.

- Adele Chatfield-Taylor, Public Member, President Emerita, American Academy in Rome

- James K. Reap, Public Member, Professor and Graduate Coordinator, Masters of Historic Preservation program, University of Georgia

- Shannon Keller O’Loughlin, Public Member, Executive Director, Association on American Indian Affairs

The Committee’s makeup was expected to balance competing viewpoints among archaeological, museum, dealer and public stakeholders regarding importation of cultural objects into the United States. But critics say that the operation of CPAC lacks transparency, that members of the art trade and collecting museums are chronically underrepresented (or absent), and that archaeological and anti-trade interests permanently fill a majority of the seats. Currently, there is only one art dealer on CPAC, instead of the three required by statute (the others do not represent dealer or collector interests), and there are four archaeologist and anthropologist members, overflowing the three designated archaeological seats.

The CPIA versus the National Stolen Property Act

A second major cause of the change in US art policy comes from the unprecedentedly aggressive enforcement of foreign nationalizing laws under the 1934 National Stolen Property Act (NSPA) – especially in the last decade. Cultural Property News will discuss the NSPA more fully in the August 2018 Newsletter of the Committee for Cultural Policy.

In brief, the transfer of objects inside the US and across federal borders is covered by multiple, sometimes conflicting laws and court-made precedents. Because of these conflicting laws, what is legal under one law may be illegal under another. The most egregiously conflicting statute with the CPIA is the National Stolen Property Act (NSPA). The NSPA makes it a criminal violation to knowingly possess, conceal, sell, or dispose of any goods of the value of $5,000 or more, which have crossed a State or US boundary after being “stolen.”

(In contrast, the CPIA (or CPIA-like laws) apply to only 20 countries (as of June 2018) and enable lawful entry of art and artifacts that can be proved to have been outside the country of origin for 10 years or more.)

The NSPA treats foreign laws that nationalize ownership of all cultural property, within certain conditions, as creating US-recognized national title in those objects. Therefore, an object sold by a private owner in a foreign country, but exported without permission of the foreign government may be considered “stolen” under the foreign government’s national ownership law. The allegedly stolen property in the US may be seized, and if deemed stolen, the object is forfeit to the US government, which eventually delivers it back to the claiming country.

*Note: The author formerly served on CPAC as a trade representative. Two other members of the Board of Directors of the Committee for Cultural Policy, which produces Cultural Property News, also served on CPAC, as museum representatives.

Part II of this article on the National Stolen Property Act will appear in Cultural Property News and the August 2018 issue of the Newsletter of the Committee for Cultural Policy.

[1] Convention on Cultural Property Implementation Act, Definitions: 19 U.S.C. §§2601(1)(2)(C)(i)(I).

[2] S. Rep. 97-564 at 2, 12 (2d Sess. 1982).

[3] The very broad definition in UNESCO is also very different from the description of “cultural item” in Section 3 of the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) as human remains, sacred objects, funerary objects, and cultural patrimony. See 25 U.S.C. § 3001(3). The 1979 Archeological Resources Protection Act, which applies to Native American and Hawaiian artifacts, has an extremely broad definition of an “archaeological resource” that covers virtually anything made by human hands over 100 years old, whether found in the ground or not. See 16 U.S.C. § 470bb(1). The National Stolen Property Act (NSPA) covers cultural property simply because cultural property is a form of “property.” See U.S.C. §§ 2311, 2314–2315 (1934).

[4] James F. Fitzpatrick, Falling Short – the Failures in the Administration of the 1983 Cultural Property Law, 2 ABA Sec. Int’l L. 24, 24 (Panel: International Trade in Ancient Art and Archeological Objects Spring Meeting, New York City, Apr. 15, 2010).

[5] Senate Report No. 564, 97th Cong., 2nd Sess. at 6 (1982)

[6] Id.

[7] See e.g. the Import Restrictions Imposed on Certain Archaeological and Ecclesiastical Material for Bulgaria (aka the Bulgaria Designated List) issued January 16, 2014 as 19 CFR Part 12 [CBP Dec. 14-01, RIN 1515-AD95, cover virtually every type of material produced in Bulgaria “from the Neolithic period (7500 B.C. through approximately 1750 A.D.”

[8] See e.g. Import Restrictions Imposed on Archaeological and Ethnological Material of Syria, 81 Fed. Reg. 53916, 53920 (2016).

[9] 19 C.F.R. §12.104(a)(2)(i).

[11] 19 U.S.C. §2602(b).

[13] William G. Pearlstein, White Paper: A Proposal to Reform U.S. Law and Policy Relating to the International Exchange of Cultural Property, 3 Cardozo Arts & Entertainment 561, 561-650, 644.

[14] Stephen K. Urice & Andrew L. Adler, Unveiling the Executive Branch’s Extralegal Cultural Property Policy 28–30 (Miami Law Research Paper Series, Working Paper No. 2010-20, Sept. 2010).

[15] Declaration of Jay I. Kislak, dated April 20, 2009, Ancient Coin Collectors Guild v. U.S. Department of State, Civ. Act 07-72074 (RSL) (U.S. D.D.C. 2009.

[16] Fitzpatrick, Falling Short, states: “In this regard, one former CPAC member has said: “…when I asked CPAC’s [legal] counsel whether I could share a dissenting opinion with someone outside the committee, I was told ‘you can, but it is probably the last thing you will do on this committee.’” (internal citations omitted).

[17] The Who, What, Why and How of the Cultural Property Advisory Committee (CPAC), 10 IFAR J. No.3-4, at 41 (2008) (Statement by Jay Kislak).

[18] Id. (Statement by Kate Fitz Gibbon).

[19] Stephen Vincent, “The Secret War of Maria Kouroupas,” Art and Auction (March 2002).

Wall and window detail of the Cultural Centre of Belém in Lisbon, Portugal, the largest building with cultural facilities in the country. By Alvesgaspar [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons.

Wall and window detail of the Cultural Centre of Belém in Lisbon, Portugal, the largest building with cultural facilities in the country. By Alvesgaspar [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons.