Book cover, Leif the Lucky by Ingri and Edgar d’Aulaire, 1941, Beautiful Feet Books; Illustrated edition (October 1, 1994). The children’s book introduced hundreds of thousands of American children to its version of the Viking discovery of the American continent.

Plans to purchase Greenland have intrigued U.S. leaders for centuries. As originally proposed by President Trump in 2019, its purchase was supposedly driven by strategic and economic interests – but earlier attempts were primarily motivated by the public’s fascination with a romanticized Viking past. American enthusiasm for linking Greenland to the United States stemmed from something else – popular myths supported by spectacular frauds linking Norse exploration to the discovery of America.

Today’s Greenlanders are pursuing independent nationhood after holding autonomous status within Denmark for decades. Greenland has been part of Denmark since 1721. Trump’s most recent announcement of its possible military and economic absorption into the U.S. has not been welcomed there. However, these events invite a deeper look at the complex history of Greenlandic-American relations and the power of fictional cultural connections in shaping identity.

The United States’ fascination with Greenland and the Viking past is a blend of history, myth, and outright fakery. The allure of the Vikings, particularly in connection to North American exploration, has inspired both legitimate archaeological discovery and a host of hoaxes. These narratives have shaped perceptions of history, cultural identity, and even geopolitics. Cultural Property News took a hard look at the most prominent frauds back in 2019; 2025 seems a good time to revisit Greenland.

The Kensington Runestone

The Kensington Runestone in the “Runestone Musuem” Alexandria, Minnesota, USA, Photo Mauricio Valle, 23 February 2018,

CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

One of the most infamous Viking-related hoaxes in American history is the Kensington Runestone, a 200-pound slab allegedly inscribed with Norse runes and dated 1362. The stone was said to have been discovered in 1898 by a Swedish immigrant, Olof Ohman. Ohman claimed to have dug it from under a large tree in the township of Solem, Douglas County, Minnesota. A University of Minnesota professor of Scandinavian Languages received a copy of the inscription and immediately declared the stone a forgery. A group of Scandinavian historians and linguists followed suit. The so-called runes actually appear to be related to modern Swedish.

Nonetheless, Hjalmar Rued Holand, a Norwegian-American historian and cherry-farmer in Wisconsin took it upon himself to bring the stone to public attention. He took the stone to Rouen and presented it for study at an international conclave of scholars, where it was roundly dismissed. Holand persisted and managed to get it displayed as a national monument in the Smithsonian Institution in 1948, but it was later quietly removed as an embarrassment. Today, while experts agree the Kensington Runestone is a fabricated relic, it remains a celebrated piece of local folklore, housed in the Runestone Museum in Alexandria, Minnesota.

The Vinland Map

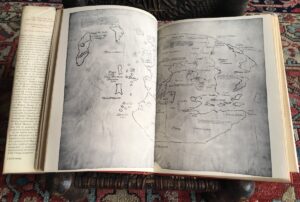

The Vinland Map is the most famous of the hoaxes that enshrine the American history of Viking exploration. What excited the interest of scholars in the map was that it showed land west of Greenland labeled “Island of Vinland discovered by Bjarni and Leif in company.” Another legend on the map mentioned a visit to Vinland in the last year of Pope Pascal (1117-1118) by an “Eric, Bishop of Greenland.”

A Spanish-Italian dealer of ill-repute named Enzo Ferrajoli de Ry sold the map to American manuscript dealer Laurence C. Witten, who then offered it to Yale University. Collector and philanthropist Paul Mellon agreed to purchase the map for between $250,000-300,000 and donate it to Yale if it could be authenticated, and if Yale would prepare a supporting book.

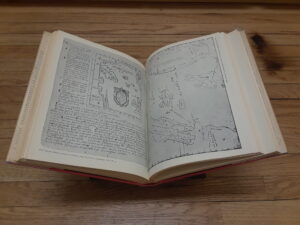

R.A. Skelton, Thomas E. Marston, and George D. Painter, The Vinland Map and the Tartar Relation, Illustration XVII Sigurdur Stefansson, Map of the North, ca. 1590, Royal Library, Copenhagen, Yale University Press, October 11, 1965

The Yale Press book, The Vinland Map and Tartar Relation appeared on October 11, 1965. (My family bought a copy.) Scheduling publication the day before the annual Columbus Day celebration stirred hard feelings among Italian Americans and apparently resulted in fisticuffs between Italian American and Norwegian American clubs in Brooklyn, New York. John La Corte, president of the Italian Historical Society, stated immediately that, “We are going to put Yale University against the wall.”

The map was an untitled pen and ink drawing on a thin parchment, bound with a manuscript text of the 1245-1247 mission of Franciscan Friar John de Plano Carpini to Tartary known as The Tartar Relation. However, even the first examiners of the documents noted problems with both its content and condition. The Vinland map showed Greenland as an island, when at the time the map was created and for long afterward it was thought to be a peninsula. It had other cartographic anomalies not found at the time it was supposedly created.

Although both documents had wormholes indicating antiquity, and were bound together, the holes did not match. A short time later, however, in what some scholars termed ‘a miraculous reunion,’ a third document, Vincent Beauvaise’ Speculum of History, was found, which had the same size parchment and identical wormholes as the map, which it was thought to have been bound at one time.

That the Vinland Map was a fake was also the conclusion of a Pennsylvania Supreme Court Justice , Michael A. Musmanno, who wrote his own book in 1966, entitled, “Columbus WAS First,” characterizing Yale’s announcement as “an outright gratuitous sneer at Columbus.”

R.A. Skelton, Thomas E. Marston, and George D. Painter, The Vinland Map and the Tartar Relation, The Vinland Map, Yale University Press, October 11, 1965

Many tests and historical analyses of the map later, the general consensus of researchers was that while the parchment is fifteenth century, the map itself is not authentic. Recently it has been subjected to additional testing including reflectance transformation imaging, or RTI, at Yale’s Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage (IPCH). Yale’s stated goal is to better determine the relationship of the map to two medieval volumes that it was found with.

The overwhelming scholarly opinion is that the map is a forgery. In March 2019, Raymond Clemens, Curator of Early Books and Manuscripts at Yale’s Beinecke Library, has stated that the map is clearly a 20th century fake, based both on the testing done over time and on the map’s content, which replicates mistakes found on a printed facsimile from 1782 of Italian mariner Andrea Bianco’s 1432 map, but not on the original.

Archaeology, the real evidence for Viking settlement

Recreated Norse buildings, L’Anse aux Meadows, dated 1021 CE, Newfoundland, Canada. Photo Dylan Kereluk, Jul 24, 2003, CCA 2.0 Generic license.

Unlike the fraudulent Kensington Runestone and Vinland Map, legitimate archaeological discoveries confirm limited Viking exploration of North America. In the 1960s, Norwegian archaeologists Helge and Anne Stine Ingstad uncovered a Norse settlement at L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland, Canada. Radiocarbon dating placed the site’s occupation around 1000 CE, consistent with the Viking sagas’ accounts of Leif Erikson’s Vinland expeditions.

The site featured the remains of sod buildings, iron-working facilities, and artifacts indicative of Norse craftsmanship. However, no further settlements of comparable significance have been found. Efforts to identify additional Norse sites, such as Sarah Parcak’s satellite-guided research at Point Rosee, yielded no definitive evidence, highlighting the limited scope of Viking ventures in North America.

So, why buy Greenland?

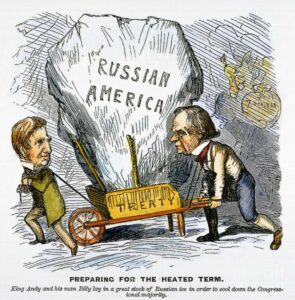

“Preparing for the heated term; King Andy and his man Billy lay in a great stock of Russian ice in order to cool down the Congressional majority”; caricature of Pres. Andrew Johnson and Sec. of State William Seward carrying huge iceberg of “Russian America” in a wheelbarrow “treaty”; refers to Seward’s purchase of Alaska in Dec. 1866. Wood engraving. Published: 1867. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-61346

The U.S. interest in Greenland extends beyond myth. Its strategic location and mineral wealth have made it a geopolitical focal point. Proposals to purchase Greenland date back to 1867 under William H. Seward – remember “Seward’s Folly,” the much-maligned purchase of Alaska? They resurfaced in 1946 when Secretary of State James F. Byrnes offered Denmark $100 million for the island. These offers highlighted Greenland’s military importance during the Cold War and its potential as a resource hub.

For nearly seventy years, the U.S. military has operated in Greenland under the terms of the 1951 Defense of Greenland: Agreement Between the United States and the Kingdom of Denmark. This treaty granted the U.S. broad authority within designated “defense areas” as part of NATO’s collective security framework.

Project Iceworm

During the 1960s, leveraging this agreement, the U.S. initiated Project Iceworm, a covert plan to construct 2,500 miles of tunnels beneath northern Greenland’s ice sheet to house medium-range nuclear missile silos. Denmark was not informed of these plans.

Photo of PM-2A Nuclear Power Plant. Photo US Army. Project Iceworm was a top secret United States Army program of the Cold War, which aimed to build a network of mobile nuclear missile launch sites under the Greenland ice sheet.

The project faced insurmountable challenges when the glacier’s instability—its faster-than-expected movement—caused tunnel collapses, ultimately leading to the project’s abandonment in 1966. However, the legacy of Project Iceworm persists. A portable nuclear reactor that powered the camp, along with associated nuclear and chemical waste, was left buried beneath the ice. At the time, it was assumed the waste would remain entombed indefinitely, but rapid climate change and rising temperatures now make its exposure likely by the end of the century, raising serious environmental concerns.

While Greenland is not for sale, as Denmark’s Prime Minister firmly stated in response to President Trump’s 2019 proposal, many Greenlanders value close ties with the U.S. They recognize Greenland’s strategic importance and see U.S. cooperation as an opportunity to bolster security and foster economic development, both critical for their aspirations toward greater independence.

The persistence of Viking myths in American culture owes much to their romantic appeal. Medieval sagas, beloved children’s books like Leif the Lucky, and modern media have elevated the Vikings to heroic status. Where would we be without Thor and his comic companions? Yet, the historical record suggests the real Viking impact on North America was brief and isolated, with no lasting influence on the continent’s development.

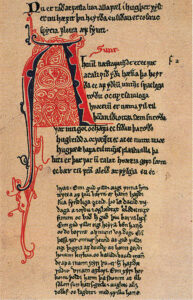

Old Norse manuscript. The Konungs skuggsjá from approx. 1250 CE contains information on the natural resource base of the Norse settlement on Greenland.

In any case, these stories—real and fabricated—continue to resonate, shaping perceptions of history and identity. The Viking myth remains an enduring symbol of exploration, resilience, and cultural heritage, even as scholars and archaeologists strive to separate fact from fiction.

Opinions within Greenland remain divided. Some view collaboration with the U.S. as the least objectionable option in a world where major powers—such as China and Russia—might seek influence over the island. Others are reluctant to sever ties with Denmark, which continues to provide substantial financial, educational, and medical support, effectively sustaining Greenland as a welfare state within the Danish Kingdom. This delicate balance reflects Greenland’s evolving political identity as it navigates its path toward a more autonomous future.

Christian Krohg (1852-1925), Leiv Eirikson discovering America, 1893, Nasjonalmuseet, Oslo, Norway, public domain.

Christian Krohg (1852-1925), Leiv Eirikson discovering America, 1893, Nasjonalmuseet, Oslo, Norway, public domain.