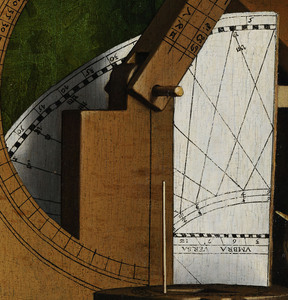

Polihedral sundial, detail from Hans Holbein Portrait of The Ambassadors. Possibly made by the German astronomer Nicholas Kratzer.

The Arts Council England has chosen Wales’ Institute of Art and Law to develop new guidelines for the restitution and reparation of cultural objects for museums in the UK. The assignment has limited funding and a timeline of only four months for completion. According to the tender, the Institute of Art and Law will work between February 24 and June 19 of 2020 to create a new, basic framework for repatriation, setting forth ethical and legal considerations to guide museums of all sizes and all types of collections. The last official guide was published in 2000 and according to the Arts Council is “out of print and out of date.” The contract was funded at a mere £42,000 barely a month after an advertisement was placed for a supplier in January.

The job was described as follows:

“The overarching aim of this work is to create a comprehensive and practical resource for museums to support them in dealing confidently and proactively with all aspects of restitution.”

Despite the contract’s call for policies applicable to all collections, the project may focus on currently fashionable aspects of restitution policy. Referring to recent French, German, and Dutch restitution and repatriation guidelines for public collections, the Arts Council stated that:

“Restitution and repatriation of objects in museum collections is an area of increasing focus and debate across the UK and international museum sector. This is particularly, although not exclusively, focused on objects in Western museums acquired by European nations from former colonies, and links to wider agendas around decolonising museums.”

Hans Holbien, Portrait of the astronomer Nicholas Kratzer making a polihedral sundial, 1528.

The Arts Council gave no definition of what “decolonization” of a museum would mean. The media has characterized the goal as seeking help in “returning looted artefacts held in UK museums.”

The Institute of Art and Law is well-respected and capable, but there appears to be a disjunct between the tasks set for it, and what a law-based analysis can provide. Many of the questions raised by calls for repatriation are not capable of a legal solution, only a moral or ethical one.

One might assume that any guidelines would recognize that repatriation is a broad term and each claim should be dealt with on its own merits. And in a fact-based analysis, all the facts are relevant, not just the ones that display inequity. None of this argues for simplistic solutions.

The very short time frame set by the Arts Council and the breadth of its stated task gives little regard to the inherent complexity of restitution policy. The future impact of a general policy on “all aspects of restitution” requires close consultation with museums and the public.

Establishing policies for restitution also requires analyzing the impact of repatriation policies on the integrity of UK collections and the choices that will be made by future museum donors in consequence of them. Establishing guidelines for specific objects will require balancing considerations of the often inadequate documentation of objects’ provenance, of how to give notice to potential claimants, how to resolve conflicting claims, and especially of the fact that there is often no legal basis for categorizing objects as ‘illegal’ or ‘looted’ in the first place. Any policy must also ensure that returned objects would have a secure future and that records be kept of any change of ownership or custody.

Comparing existing models for restitution

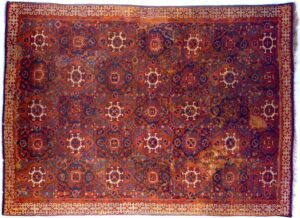

Holbein carpet with large medalions, 16th c., Central Anatolia, Turkey.

Will the Institute of Art and Law be able to do in four months what – despite the US Congress’ eagerness to rectify clear wrongs in the taking of objects and human remains –took years of hearings to establish in the case of Native American objects only?

Neither the UK nor most EU counties have yet developed comprehensive processes for returns to indigenous communities, as the US did under the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). NAGPRA requires museums to inventory all items, and mandates a claims process through which museums and tribes determine whether items are grave goods, items typically associated with grave goods, sacred or ceremonial items, or objects with important historical associations to tribes and individuals within tribes. Despite real dedication and effort on the part of museums, thirty years after passage of NAGPRA, Native ‘ancestors’ bones still rest in huge quantities in US museums and other cultural institutions, and there is not agreement among museums about which types of artifacts are sacred or ceremonial items and therefore appropriate to repatriate.

Under NAGPRA, human remains, “objects of cultural patrimony” and “sacred objects” are deemed inalienable from their original Native owners. Such items, once claimed by one of 574 federally recognized tribes, must be returned to the proper tribe. It should be noted that return of “sacred objects” is not based upon a ceremonial role that the object had at one time. Sacred objects are returned if they are currently required for the exercise of “traditional Native American religion.”

Over its three decades of operation NAGPRA has not always worked to the satisfaction of either tribes or museums. For many tribes, its processes have taken too long; for museums, claims have been too broad and funding for the burdensome inventories mandated by federal law has been minimal or nonexistent. Some long-time US observers are concerned that objects not deemed suitable for repatriation in the past are now considered either sacred objects or objects crucial to tribal identity and are being returned without legal justification to tribes. (See Ron McCoy, Is NAGPRA Irretrievably Broken, Cultural Property News, December 19, 2018.

Righting wrongs

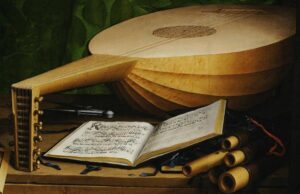

Detail of lute from Hans Holbein’s The Ambassadors.

In general, UK and EU museums have been slower to act than US museums on requests for the return of human remains to indigenous peoples. Recent calls for repatriation have been aligned with campaigns for long-overdue indigenous rights and for full recognition of independence from a colonial past. However, consultations between indigenous communities and museums are increasing and human remains originally taken for scientific study (sometime to support spurious race-based theories of superiority) have been quietly returned to Australia, New Zealand, and elsewhere. A number of UK museums have recently made other important repatriations; in November 2019, the Manchester Museum returned forty-three sacred and ceremonial objects to the Aranda people of Central Australia, Gangalidda Garawa peoples’ of northwest Queensland, Nyamal people of the Pilbara and Yawuru people of Broome.

However, righting obvious wrongs and confirming indigenous peoples’ rights to essential cultural objects is not the only concern with ethnographic artifacts. Whatever guidelines are issued regarding the ethics of returning indigenous peoples’ art also need to address the need for and practicality of massive returns, to ensure that documentation takes place, and to consider shared ownership and other alternatives to direct repatriation. Serious consideration should be given to ensuring that the UK’s diverse public continues to have access to global works and can see every world heritage honored in UK museums.

One positive direction would be to recommend additional funding to UK museums, many of which have already significantly expanded their cooperation with foreign cultural institutions, working directly with colleagues in the developing world and sharing their expertise to train, teach, and help to build new institutions there.

Antiquities and ethnographic materials present complex legal issues

Detail form Hans Holbein’s The Ambassadors, showing the ‘torquetum’, an instrument for taking simultaneous horizon, equitorial, and elliptic co-ordinates.

There is no space here to discuss the longstanding and problematic issues surrounding antiquities – except to state that before tackling it, the UK researchers must endeavor to sweep away the numerous egregiously false stories about the size of the antiquities trade, the ludicrous notion that money laundering is pervasive in this very smallest, less than 1% segment of the art market, and to acknowledge the total lack of evidence of any association with terrorist funding. It should be noted that another slew of misleading claims has recently been made, stating that only a tiny percentage of Middle Eastern antiquities traded are legal. This entirely contradicts the actual results of the ILLICID study in Germany. These misleading stories could be very harmful to the ability of UK museums to accession legally acquired artworks.

Instead, researchers must look at the facts in order to analyze whether repatriations of works acquired 25, 50, 100, 200 yeas ago or more should be returned. If the facts of source country actions (and inaction) rather than laws that exist only on paper are considered, it will be very difficult to establish a ‘legal’ basis for repatriation of antiquities. Over the last fifty years, most nations have signed the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property. However, signing a paper declaration is not enough to change source country behavior – or to mandate returns.

While many nations have passed blanket laws making export illegal or even nationalizing ownership of all cultural property since 1970, virtually no country outside of the developed world has ever established official permitting systems for export of any objects, however duplicative. At the same time, very few art source countries enforced either export or nationalizing laws domestically until the late 20th – early 21st century. Instead, most source countries turned a blind eye to the undocumented export of millions of archaeological and ethnological objects supposedly covered under nationalizing laws. These entered Western countries as legal imports and now sit in museums and private collections.

Holbein carpet, 15th–16th century, wool, from Turkey, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Repatriation and accession policies go hand in hand. Both tend to be written aspirationally, not practically, and have failed to be limited to key objects or to require solid justification for returns. They also tend to be strictly applied by museums within developed nations. For example, the “guidelines” on acquisition set forth by the Association of Art Museum Directors in 2008 and 2013 were explicitly subject to modification based upon circumstances but they resulted in most US museums adopting rigid rules against accessioning any object without proof of legal export from its source country after 1970. Since few source countries ever issued official permits, and those that did, like Egypt up through 1983, have inadequate descriptions, the result was to make hundreds of thousands of privately-owned objects into “orphans” that could not find a home in museums, even as gifts. The lack of documentation today became an insurmountable barrier for objects legally imported into the US decades before. Surely, museums in the UK would wish to avoid being locked in to similar restrictions.

Workable and unworkable models

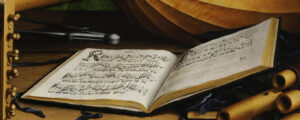

Lutherian songbook, German, detail from The Ambassadors.

Museum repatriations have been one of the most widely discussed and controversial aspects of museum management since French president Emmanuel Macron promised during a 2017 trip to Africa to make the restitution of objects of African heritage a priority. Macron commissioned a major report by Bénédicte Savoy and Felwine Sarr, Rapport sur la restitution du patrimoine culturel africain, published in 2018, on how that might be accomplished, yet its controversial recommendations were not generally accepted by French museums and cultural officials. (See Savoy-Sarr Report on African Art Restitution: A Summary, Cultural Property News, January 30, 2019.)

The Savoy-Sarr report was polemic rather than based upon legal argument. It was widely criticized for its practical and logical flaws, including its call to return the vast majority of all African art from France as “looted,” its inaccurate depictions of the history of collecting, and its blanket characterization of all art transactions in which there was any disparity of power between seller and buyer as theft. (If artistic wealth is ‘stolen’ if not acquired in an absolutely symmetrical power relationship, then most transfers of art (and other goods) could be so classified.)

The report dismissed concerns that most African nations currently do not have the infrastructure to preserve or present millions of artifacts if they were returned. Nor did it consider the merits of French museums starting the process by working together with foreign colleagues to build uniquely African cultural institutions, and only later making decisions about the repatriation of objects

Nor did the Savoy-Sarr report deal with the fact that African resources of far greater economic value than art, most especially mineral wealth capable of supporting massive domestic development including cultural, educational, and health institutions of all kinds, continue to be drained from the continent by multinational corporations and corrupt regimes. This ‘looting’ has been a serious impediment to the development of a cultural infrastructure to hold returned artifacts.

Repatriation ‘guidelines’ proliferate but actions vary

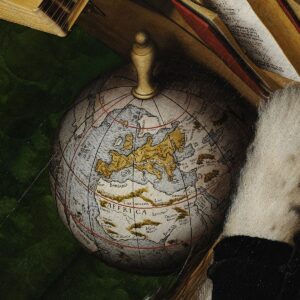

Detail of terrestrial globe in Holbein’s The Ambassadors, of a type possibly based upon a lost globe of 1523 by Johannes Schoner, from Germany.

European and American museums have faced increased press and public pressure to repatriate artifacts deemed “stolen” in the court of public opinion. Sixteen German states issued a joint declaration in March of 2019 that directed the country’s state-managed museums to develop processes that would facilitate repatriation for objects that were taken in “legally or morally unjustifiable” ways from former colonies. What the state ministers actually did was agree to prioritize return of human remains and documentation and provenance research for other objects.

Dutch museums also developed guidelines last year for repatriation of colonial-era artifacts in public collections and museums that focused on objects taken without the consent of the holder in the colonial era. The director of the Museum of World Cultures used some of the phrasing of the Savoy-Sarr proposal, speaking of “power discrepancies” and “stolen objects.” However, the steps already taken by the Rijksmuseum to discuss repatriation have focused on items with a clear history of looting or seizure by Dutch military and colonial authorities.

For all the aspirational excesses found in the discussion of repatriation today, it is hoped that the UK report will be informed by the Dutch and German statements on the importance of doing research and documentation first, and on the failure of the Savoy-Sarr proposal to gain traction within the museum community in France. The Institute of Art and Law could also consider lessons offered in the successful Utimut agreement between Denmark and Greenland, a continuing process to establish a fair distribution of Greenland art and artifacts between Denmark and its Danish Commonwealth partner. (See Successful Repatriation: The Utimut Process in Denmark & Greenland, Cultural Property News, November 28, 2019)

There are bright spots among repatriation efforts that show how art dealers and collectors have accepted and internalized the ethical bases for repatriation. This grassroots action shows how the public’s perceptions of the issues have altered. This kind of change is likely to have more far-reaching consequences than any ‘guidelines’ or even changes to the law. The grassroots Voluntary Returns Program developed by the ATADA ethnographic art dealer organization in the US is a model of community action. This entirely voluntary program avoids government involvement; it deals with objects in private collections rather than federally-funded museums. The program is remarkably efficient; it has already brought over 200 key sacred objects used for current religious activities to tribal communities in the American Southwest at no cost to them. ATADA does not make determinations regarding the sacred or communal status of specific items of the various tribes. Historic photographs and publications may indicate ceremonial status, but similar objects have different roles in different tribes. When returns are facilitated through ATADA, the organization takes advice directly from the elders, spiritual leaders and heritage officers of the tribes to determine if a return is appropriate.

In contrast, almost all repatriation today takes place between governments. Objects do not go back to communities or individual families, but rather to political entities who may make use of them for their own purposes; concepts of ‘identity’ and ‘heritage’ have often been used to promote nationalist or short-term political goals.

There are many questions about where repatriation is most beneficial and useful, and where it is unwarranted. Should repatriation be for the purpose of continuing an active and viable culture in which objects retain powers beyond the mundane? One answer will not fit all cultural communities – not all want their power objects back. In a few cases, indigenous peoples view their artworks as ‘delegates who act on behalf of their culture,’[1] for others, selling sculptures to outsiders is the equivalent of the tradition of leaving them to rot in the forest,[2] still others gave up old idols to missionaries as part of the adoption of a new Christian faith. And for some, the return of sacred objects is essential to repair the world; their absence from the tribe is damaging to all peoples, whether those outside the tribe know it or not.[3]

Repatriating antiquities to unstable regions raises questions of preservation and ownership

Detail from Hans Holbein’s The Ambassadors, showing a quadrant, used for taking angular measurements of altitude in astronomy and navigation, typically consisting of a graduated quarter circle and a sighting mechanism.

Does returning a sacred object to a community where it is utilized for spiritual practices have a different value than returning a 4000 year old statue to a modern government? Everyone is familiar with the longstanding legal, ethical and identity-based arguments surrounding the Parthenon Marbles, but what about situations where governments are doing real harm to heritage?

When the Taliban announced plans to destroy both the Bamiyan Buddhas and the contents of the Kabul Museum in Afghanistan, UNESCO dithered so long about whether it was permissible ever to allow artifacts out of a country of origin that it was too late to save them, and thousands of artworks were destroyed.

That lesson was not lost on museums in the US, which responded to the destruction by ISIS in Iraq and Syria by offering temporary ‘safe harbor’ to objects. So far, the offer has not been taken up by any Middle East/North African countries. This situation raises still other questions about balancing the ideal of keeping objects in place against the risk of destruction or loss due to inadequate cultural infrastructure and the desire for the object’s safety and preservation,

Should there be returns today to unstable and irresponsible governments as in Libya, Syria and Yemen, when artifacts are still at risk of destruction in war? Should returns be undertaken when established governments are actively demolishing monuments of minority cultures, despite having adopted laws guaranteeing their preservation, as in the case of destroyed Tibetan lamaseries and ancient Uyghur mosques and cemeteries in China.

Less pressing but vexing questions also arise when the modern country that the artworks came from cannot be determined. The creation of new nations magically creates new ‘national identities’ and ‘national heritage.’ In addition, many boundaries drawn by Russia, France, Germany and other empirical powers as well as England during the colonial era deliberately divided ethnic groupings and alliances.

Lute; Chordophone-Lute-plucked-fretted, Rosewood, ivory, wood, ebony German, 1596, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication

Discussion of all these issues is very welcome, as is greatly expanded cooperation and sharing of resources between UK and global institutions. The first step should be in committing to joint projects and testing the waters by making significant loans, providing training in museum skills, exchanging perspectives and building trust on all sides. The Arts Council England has brought together distinguished scholars such as Professor Janet Ulph from the University of Leicester to work alongside the Institute for Art and Law as it conducts its research. The steering group overseeing the project includes the Museums Association, the International Council of Museums (ICOM) UK, the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, along with the Northern Ireland Museums Council, Museums Galleries Scotland, and the Museums and Archives Division of the Welsh Government. Each organization can contribute to answering the practical and philosophical questions raised here.

The guideline publication is currently planned to be issued in the fall of 2020. It is not clear how the Institute of Art and Law will be able to assess the complexities of repatriation policy in so short a time – or to find the right balance between calls for repatriation and museum goals of preservation and scholarship – or with the museums’ fundamental mission to provide public access to art of all counties, cultures, and periods.

The need for policies to assist museums through the maze of repatriation claims and counterclaims is clear. The time to start is now. What is doubtful is whether a few months’ consultation will render a well-considered or workable basis for future policy.

[1] Simon Schaffer, ‘Get Back. Artifices of Return and Replication,’ The Aura in the Age of Digital Materiality, 96-97.

[2] Id. at 94. An example is the sale of the malangan carvings of New Ireland in the Bismarck Archipelago.

[3] Id at 95, 98. This is also the explanation given by Zuni leaders to participants in the ATADA Voluntary Returns Program when an Ahayuda and several masks were returned, including masks the Zuni identified as fakes, but which they deemed too close to the originals to be allowed to circulate in the world.

Hans Holbien, The Ambassadors, Jean de Dinteville, French Ambassador to the court of Henry VIII of England, and Georges de Selve, Bishop of Lavaur. 1533, National Gallery, London. The painting depicts luxury goods and scientific instruments from many countries showing the extent of such trade in the 16th century.

Hans Holbien, The Ambassadors, Jean de Dinteville, French Ambassador to the court of Henry VIII of England, and Georges de Selve, Bishop of Lavaur. 1533, National Gallery, London. The painting depicts luxury goods and scientific instruments from many countries showing the extent of such trade in the 16th century.