On February 23, 2018 the United States signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with Libya to restrict importation of objects of ‘Libyan cultural heritage’ made prior to 1911. Jewish groups are outraged and say the MOU legitimizes the confiscation of Jewish property seized by Libya’s government when they were forced from the country. Others in the cultural policy world are wondering why the US government would put faith in Libya to act responsibly to safeguard the heritage of minority and exiled peoples. Libya poses “an unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security and foreign policy of the United States,” according to a Notice Regarding the Continuation of the National Emergency with Respect to Libya, issued a mere two weeks prior to the signing of the MOU.

Jewish Flight From Libya

Soldier conducting the choir at the Jewish School in Benghazi, 1944. Beth Hatefutsoth Photo Archive http://dbs.bh.org.il

As did Jews in Iraq, Syria, Egypt and other Middle Eastern nations, Jews in Libya experienced years of persecution prior to their expulsion. National governments eliminated Jewish civil and property rights and turned a blind eye to violence against them, causing many Jews to emigrate in the first half of the 20th century, despite having to abandon their homes and property.

The vast majority of the remaining Jewish minority communities were expelled en masse from Arab nations after the Six-Day Arab-Israeli War of 1967.

Gina Waldman, president and co-founder of Jews Indigenous to the Middle East and North Africa (JIMENA) recounted her flight in an interview with Josefin Dolsten of the Jewish Telegraphic Agency (JTA),

“I am a Jew who escaped from Libya in 1967 with the clothes on my back and $20 dollars, because that’s all that we were allowed to take with us.

Our communal property, which included all of our artifacts, torah scrolls, archives and religious items were forcibly confiscated from my 2,000 year old Libyan Jewish community in 1967, when the Libyan Government expelled us.

I strongly protest the fact that this MOU doesn’t take into account that our own Jewish patrimony doesn’t belong to the Libyan government, it is the legitimate private property of the Libyan Jewish community and therefore should not be included in this MOU.”

The Flawed Libyan Request and Suspicious Circumstances Surrounding Recommendations for an Agreement

Jewish Brigade soldiers at an archaeological site in the Benghazi area 1943-1944. Beth Hatefutsoth Photo Archive http://dbs.bh.org.il

Libya’s precipitate request for an agreement with the US on cultural property last year was met with disbelief by many in the art community, including the Association of Art Museum Directors, which submitted a scathing Statement of the AAMD Concerning the Request by Libya. The State Department announced the proposed agreement the day before the Fourth of July holiday and less than a week was allowed for public comment.

In addition to protesting the rushed request, there were clear questions about Libya’s ability to meet the criteria for granting import restrictions outlined in the Convention on Cultural Property Implementation Act (CPIA).

Among the requirements for an agreement under the US law, the country must show that it “has taken measures consistent with the [UNESCO] Convention to protect its cultural patrimony,” and that the import restriction “is consistent with the general interest of the international community in the interchange of cultural property among nations for scientific, cultural, and educational purposes.”

The Public Summary of Libya Request drafted by the Department of State (the original request by Libya was never provided) acknowledged that there was no government capable of administering cultural heritage in much of the country. The State Department summary stated that:

- “[A]rtifacts, which had been excavated from temples, were also stolen from the storerooms.”

- “Museums have also been vandalized and looted by invading militias.”

- “There are also reported thefts from museums and storerooms of documented and undocumented objects.”

- “[A]ll of the country’s twenty-four museums are closed.”

- Lacking government support, Department of Antiquities staff “continue to take personal responsibility for the objects housed in their institutions.”

By its own acknowledgement, Libya could not meet the US criteria for an agreement, yet the Department of State first recommended emergency unilateral restrictions, which were put in place in December 2017, and then, on February 23, 2018, a full bilateral agreement was signed. According to sources, the State Department’s Cultural Property Advisory Committee (CPAC) had not approved a full bilateral agreement. In addition, hints about CPAC’s rejection of inclusion of Jewish and minority property have since filtered out from the committee. Nonetheless, articles of Jewish heritage were included in the Designated List.

The ‘emergency’ terms of the agreement voted on by CPAC appear to have been transformed – perhaps by magic? – into a fully-fledged Memorandum of Understanding during its journey through the State Department.

When the State Department makes a recommendation different from that of the Cultural Property Advisory Committee, it is supposed to report to Congress, stating the difference in the recommendation and the reason for it. No such report appears to have been made.

Emergency Restrictions Including Jewish Artifacts Issued by US Customs

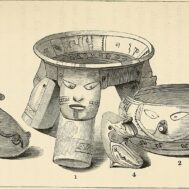

On December 5, 2017 the United States issued a Designated List of Archaeological and Ethnological Material of Libya as part of the Emergency Import Restrictions Imposed on Archaeological and Ethnological Materials From Libya. This list is illustrative rather than inclusive, and it specifically names items of Jewish patrimony.

In the section pertaining to ‘archaeological’ material (at least 250 years old), the Designated List includes, “…scroll and manuscript containers for Islamic, Jewish, or Christian manuscripts.” In the same section, under stone sculpture, “Architectural Elements” from synagogues are specifically included. Many more items of Jewish heritage are covered within the general descriptions. Any items from Libya on the Designated List entering the US could be seized and sent back to Libya.

Gina Waldman and other Jewish leaders say that this legitimizes the forced confiscation of Jewish community property and gives ownership rights to Jewish patrimony to the Government of Libya. She asks, “If a Nazi looted Torah or any religious item was to appear in the United States, would the State Dept. give it back to the German government?”

Long before Libyan strongman Muammar Gaddafi’s fall, the Libyan government encouraged the eradication of all memory of its former Jewish community. Its government deliberately damaged and then sealed off synagogues, and built shopping malls on top of ancient Jewish cemeteries, tossing aside bones and boxing up skulls and remains and throwing them into a storeroom.

Art is a Pawn in a Chaotic Civil War

The Arch of Marcus Aurelius in Oea, modern Tripoli near the northeastern entrance to the Medina. Erected by Gaius Calpurnius Celsus to commemorate the victories of Lucius Verus, junior colleague and adoptive brother of the Emperor Marcus Aurelius, over the Parthians in the Roman–Parthian War of 161–66, Photograph 21 March 2017, Author: Dr Esam Tabone, Wikimedia Commons.

Today, Libya is a highly unstable country with multiple ruling cliques. At least three ruling entities are fighting over territory, and many smaller militias are making and changing alliances while striving for power. The US Embassy in Libya closed in 2014 – it is located now in Tunisia.

The Libyan Request stated that there were immediate threats to its sites, monuments, and cultural heritage. However, Libya’s commitment to protecting monuments is contradicted by statements of Libyan government officials. In fact, the Libyan government has denied the necessity for protections to monuments damaged by graffiti and threatened by military actions.

On June 11, 2017, Libya’s General Tourism Authority (GTA) criticized the decision of the UNESCO World Heritage Committee to place five archaeological sites in Libya on the endangered world heritage list. The statement alleged that the UNESCO World Heritage Committee placed the sites on the list “without any regulatory, legal or logical actions.” The GTA urged local authorities to “shoulder their responsibilities and take necessary measures to protect and preserve cultural heritage.”

The five sites placed on the World Heritage danger list were Leptis Magna, the ancient city of Sabratha, Cyrene, the rock art site of the Akakus Mountain and Ghadames. In an interview with on August 7, 2016, archaeologist and head of Leptis Magnis Control Committee Ezzedin Fagi stated that the vandalism and sabotage at Leptis Magnis were falsely described in the UNESCO report. He said that Sabratha and Ghadames are also in good condition, and that his department was preparing a report to correct the UNESCO claims.

Libya has not taken steps to protect its cultural heritage, as required by the statute.( 19 U.S.C. § 2602(a)(1)(C0(i)) On May 15, 2017, Libya issued a list of incidents of items stolen from Libyan museums dating back to WW2, 75 years ago. One allegedly stolen statue on the list has been on public exhibit at the Cleveland Museum of Art for more than 25 years, and has never been claimed by Libya.

More recent historical structures are also at risk. In early March, the Libya Observer reported the shelling of Fort Elena, (formerly Fortezza Margharita), a historic castle in Sabha dating to the Italian colonial period. Safa Alharathy of the The Libya Observer reported that, “The Libyan Antiquities Authority (LAA) has condemned the destruction of Sabha’s historic castle after its walls were severely damaged by missiles during the clashes in the city.”

Further in the article: “The LAA stressed that it will continue to demand the establishment of a law that promotes and protects the cultural heritage in Libya, which forms an essential factor in human development.”

Sabha has been the site of civil unrest that has escalated in recent days with military clashes causing as many as 900 people to flee the area. Throughout Libya’s civil war, Fort Elena has frequently been used as a military installation, drawing destruction from opposing forces. This provides scant reassurance that Libya has the infrastructure in place to protect its cultural heritage, or to maintain a government for that matter.

Better options exist than to delegate absolute authority and control over the heritage of many peoples to a government that barely exists. Or for the US to claim to be helping by denying entry to all Libyan antiquities when there is no demonstration that there is a US market for them.

Libyan cultural officials should be given financial and technical assistance to document vulnerable antiquities and sites to be sure that there is never a market for artifacts looted from them, and Libyan cultural authorities encouraged to take advantage of US and European museums’ offers to securely store movable items until peace enables their safe return.

And as for the exiled Jewish and Christian communities, they say that their rights over their own communities’ cultural heritage, rescued from a hostile government, surely should be protected, and acknowledged to be their own.

The Jewish School in Benghazi (Libya), 1944, established by Jewish soldiers. The teachers and students. Widener Library, Cambridge, Massachusetts

The David B. Keidan Collection of Digital Images from the Central Zionist Archives: Photographs on the History of Zionism and Israel. Wikimedia Commons.

The Jewish School in Benghazi (Libya), 1944, established by Jewish soldiers. The teachers and students. Widener Library, Cambridge, Massachusetts

The David B. Keidan Collection of Digital Images from the Central Zionist Archives: Photographs on the History of Zionism and Israel. Wikimedia Commons.