On March 17, 2021, a request from the Republic of Albania seeking import restrictions on virtually all Albanian art, ethnographic objects and archaeological artifacts into the United States will be heard by the Cultural Property Advisory Committee (CPAC) at the State Department’s Cultural Heritage Center, in its Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs.

The Committee for Cultural Policy[i] and Global Heritage Alliance[ii] submitted testimony on the Albania request[iii] explaining that the request fails to meet U.S. legal requirements. In part, this is because:

- Albania has provided no evidence establishing that there is a U.S. market in looted art of any kind from Albania; and

- there isn’t any data showing illegal import or U.S. sales of looted Albanian art in official U.S. records either.

Since there doesn’t appear to BE any market for looted Albanian ethnographic art and antiquities in the U.S., why are we bothered?

Because this application for import restrictions and the mere possibility that import restrictions will be granted by CPAC makes a mockery of a good U.S. law and the best intentions of the U.S. Congress that passed it.

The US Department of State, which has encouraged the creation of art blockades regardless of their origin, has provided a list of the proposed restricted objects:

“The archaeological materials requested date from the Middle Paleolithic to the Ottoman Period, and include stone, ceramic, metal, glass, wood, and other organic materials. The ethnological materials requested date from the Byzantine, Middle Age, and Ottoman periods and include sacred icons and frescoes, written material such as illuminated manuscripts and codices, traditional clothing, religious vestments, ceremonial paraphernalia, and architectural elements, sculptures, mosaics, and reliefs found in historical or religious structures.”[iv]

Antique shop without any real antiques – Old Bazar, Kruja, Albania, photo by Klejdi Shtrepi, 21 April 2018, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

In other words – the import restrictions would cover every form of art or artifacts known ever to have come from the region known today as Albania, from 300,000 BCE to the early 20th century.

This proposal is typical of the ‘wall-to-wall’ embargoes signed under the guidance of the Cultural Heritage Bureau at the Department of State, unjustified by either the facts or by the law, which calls for targeted restrictions based upon evidence of significant looting.

“…On their face, wall-to-wall embargoes fly in the face of Congress’ intent.[v] Congress spoke of archeological objects as limited to “a narrow range of objects…”[vi] Import controls would be applied to “objects of significantly rare archeological stature…As for ethnological objects, the Senate Committee said it did not intend import controls to extend to trinkets or to other objects that are common or repetitive or essentially alike in material, design, color or other outstanding characteristics with other objects of the same type…[vii]”

The Public Summary seeks restrictions on ethnological items from the “Ottoman” period. Typically, “Ottoman” items do not meet the above definition of “ethnographic” items under the CPIA. The term “Ottoman” is a general description of a period of political rule in which a wide range of sophisticated commercial products were manufactured by professional artisans in multiple Mediterranean countries. Unquestionably, many decorative objects of metal, glass, wood and stone were made throughout the territories of the Ottoman Empire and then sold widely in an active trade. Ottoman-style goods, wherever produced, are repetitive, essentially alike, and the products of urban cultures. How are they ‘ethnographic’ if they were acquired through the market? They cannot be characterized as ‘ethnographic’ under the CPIA. Antique jewelry and antique textiles and costumes from Albania, such as are illustrated in old photographs, left the country many decades before – those that remain are safely housed in the country’s museums. Only replicas are available in today’s tourist venues.

The only Albanian objects currently in the U.S. market are low value coins, often copies made to imitate the coins from Greece and other regions whose coinage was most widely circulated in ancient times. Coins are among the most common and generally the least valuable ancient artifacts. They are the artifacts most often found accidentally, having been dropped and not missed in ancient sites, or found in small hoards that were hidden away from invaders or marauding bands in war and times of instability. Hoards are not generally located in archaeological sites; they often turn up during house reconstruction or in plowed fields where they were hidden centuries before.

U.S. law states that import restrictions must be of substantial benefit in deterring a serious situation of pillage. A measure of whether an MOU would reduce the jeopardy of pillage is whether there is a market in pillaged material in the U.S. and other states imposing import restrictions. Section 303(a)(1)(C) of the CPIA states that U.S. import restrictions may be implemented only if:

“the application of the import restrictions set forth in section 307 with respect to archaeological or ethnological material of the State Party, if applied in concert with similar restrictions implemented, or to be implemented within a reasonable period of time, by those nations (whether or not State Parties individually having a significant import trade in such material, would be of substantial benefit in deterring a serious situation of pillage…)”

It is completely illogical to argue that pillaging will be reduced through import restrictions if there is not a significant import trade with the U.S. to begin with. The Albanian request fails to show that the U.S. or any other nation is a significant marketplace for recently looted Albanian antiquities. The Public Summary provides no evidence of looting of items from Albania, nor any evidence of a market for archaeological goods in the United States. Our research provides no evidence supporting this claim either.

Edward Lear (1812-1888), The falls of the Kalama, Albania 1851. Public domain, Wikimedia Commons.

There are no auction records from Sotheby’s or Christie’s, the largest auction houses in the U.S., of any sales of antique or ancient objects from Albania. None. In fact, there does not appear to be any significant market for Albanian antiquities or ethnographic materials anywhere. Under these circumstances, U.S. import restrictions could not possibly have a significant effect in preventing current looting in Albania. That requirement for imposing import restriction under US law cannot be met.

The vast majority of antique items resulting from any search of “Albania” items for sale at auction are books, lithographs, prints and paintings produced by travelers (including the poet and painter Edward Lear) to Albania and depicting its people, their costumes and its dramatic landscapes.

The only objects actually from Albania offered for sale by Sotheby’s anywhere in the world in the last twenty years are:

Six (6) Albanian flintlock holster pistols from the late 18th/19th Century, all sold in an auction for lower value goods in London in 2002.[viii]

The only objects from Albania offered for sale by Christie’s anywhere in the world in the last twenty-five years are:

Coins made between 1926 and 1939 (sold mostly in a single auction in the 1990s), unused postage stamps from 1929 which sold in 1999 in London, fewer than a half dozen military medals in scattered low value auctions, and one (1) 19th C Albanian long gun sold in 2012 in London.[ix]

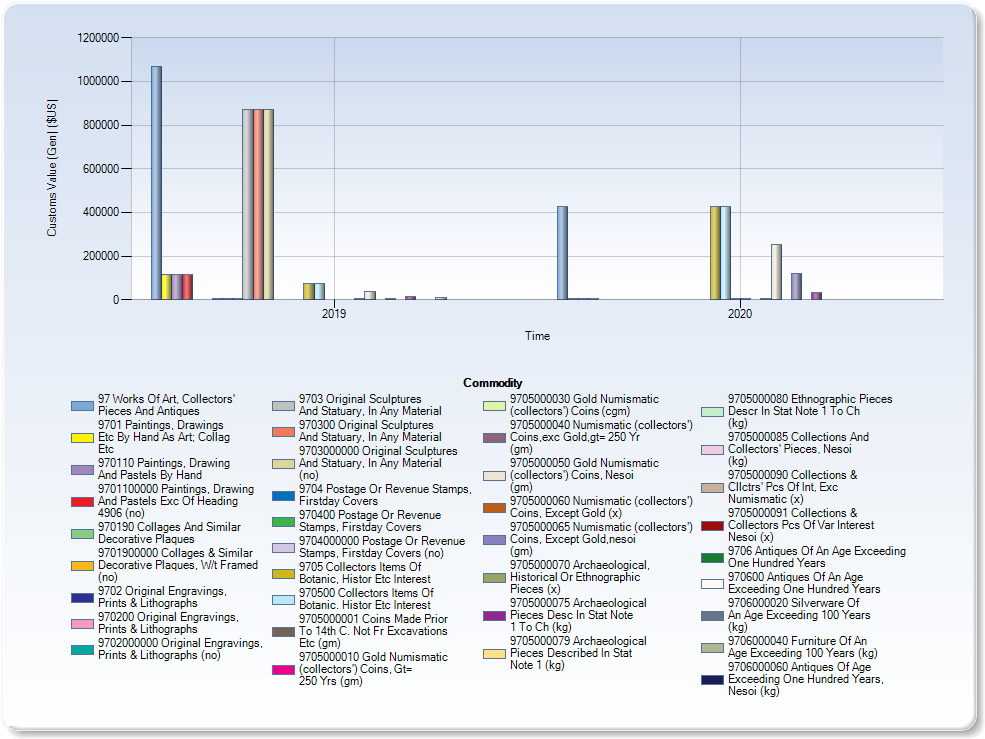

There are U.S. records of all imports of Albanian materials brought into the United States. They show almost no trade either. These data spreadsheets and charts show the importation of objects of Albanian origin entered into the United States from 2002-2020. (See Albania Country of Origin Imports Art 2015-2020 and Albania All Art Imports.)

Albania Country of Origin, all art imports contemporary, modern, antique and archaeological. Source U.S. Census data.

All U.S. customs duties and object classifications are based on the country of “origin,” that is, of manufacture. The exporting country is not noted. Therefore, these official records do not show imports from the Republic of Albania, only goods of Albanian origin. These are goods of Albanian origin that may have entered the United States from any country in the world, including but not limited to Albania itself.[x], [xi]

Reproduction of a statue of Aphrodite in Seferan, by the Liqeni i Rumbullakët. Photo by Pasztilla aka Attila Terbócs, 13 October 2018, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

What these charts and graphs show is that the U.S. does not import significant amounts of any Albanian art or antiquities from any country. The U.S. imports from Albania in the art field vary a great deal from year to year, so we have provided charts for years 2002 to 2020. Within these nineteen years, the vast majority of art imports are original statuary less than 100 years old ($872,635 in 2019, $0 in 2020), paintings and drawings by hand ($115,960 in 2019, $3000 in 2020) and collections of botanical and historic interest ($74,026 in 2019, $425,872 in 2020). (Perhaps this relates to Albania’s fame as a source of perfume plants.) Collector’s coins (non-archaeological) imports were $0 in 2019, $7,048 in 2020, and coins more than 250 years of age were $14,372 in 2019, $35,486 in 2020.

The entries for 2019 and 2020 for “antiques over 100 years of age” are zero – and there are zero entries for “ethnographic” pieces as described in the CPIA, when the more detailed Harmonized Tariff classifications came into force.

In contrast, Albania’s top exports, recorded in 2019, are leather footwear ($352M), footwear parts ($230M), crude petroleum ($189M), ferroalloys ($129M), and non-knit men’s suits ($116M). Top export partners are Italy ($1.21B), Spain ($216M), Germany ($161M), Greece ($143M), and France ($95.1M). In the last five years, the total exports of Albania have changed by $313M from $2.36B in 2014 to $2.67B in 2019.

Furthermore, Albania’s entry into the E.U. will provide an opportunity for legal trade in the same materials covered in the proposed agreement. The same Albanian art and artifacts that are legally sold in the E.U. will be illegal to import into the U.S. The Republic of Albania is currently seeking admission to the European Union. According to a statement by the European Commission:

“Albania applied for the EU membership in April 2009 and received the candidate status in June 2014. In April 2018, the Commission issued an unconditional recommendation to open accession negotiations. The Council set out the path towards opening accession negotiations in June 2019, depending on progress made in key areas such as the judiciary, fight against corruption and organised crime, intelligence services and public administration. In March 2020 the members of the European Council endorsed the General Affairs Council’s decision to open accession negotiations with Albania and in July 2020 the draft negotiating framework were presented to the Member States.”[xii]

Accession to the E.U. would render U.S. import controls on Albanian goods circulating within the E.U. meaningless. CPIA import restrictions only apply to cultural goods subject to the export control of a particular country.[xiii],[xiv]. As stated by Peter K. Tompa, executive director of Global Heritage Alliance:

“U.S. Customs and Border Protection has failed to acknowledge that E.U. member countries are part of a common market that allows for the export of archaeological and ethnological objects with or without a license according to the local law of the exporting E.U. member. Allowing entry of objects legally exported from the E.U. that are found on “designated lists” for E.U. member countries would greatly facilitate lawful trade in a situation that could not have been specifically contemplated by the CPIA, which predates the E.U.’s export control regime. This can be simply accommodated by modifying Art. I of any MOU with Albania to make any import restrictions inapplicable to cultural objects legally exported from another E.U. country, with or without a formal export permit under local law.”

When Albania joins the E.U., its antiquities and art would no longer be subject to the recently established E.U. import controls. The result of including this language in Article 1 would be to facilitate a lawful trade in art already in lawful circulation among E.U. members, and lawful trade is a clear goal of the CPIA.

Albania is a lovely place to visit, but having a few ancient sites does not make it a source country for looted art. Tourism is a major source of income for Albania (1.5 billion euros annually, before Covid) and the tourism sector is expected to increase. The Spanish Millennium Development Goals Achievement Fund has sponsored and funded the Culture and Heritage for Social and Economic Development Programme (CHSED) in Albania,[xv] implemented jointly by UNESCO and UNDP, and working in conjunction with the Albanian Ministries of Tourism, Education, Cultural Monuments, and Foreign Affairs. The program’s goal is to popularize all forms of Albanian culture within both the domestic and international tourism framework. By linking cultural activities, history, and education about culture to everyday life, the program hopes to revitalize crafts, modernize facilities for tourism, and ensure a more robust cultural life within Albania.

The ruins of the antique theater of Hadrianopolis near Sofratika, Albania. Photo by Pasztilla aka Attila Terbócs, 14 August 2017, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

While natural beauties and an unspoiled countryside are major attractions, Albania also has five fairly well known historical sites. The most famous is the ancient Greek colony and bishopric of Apollonia. The archaeological park surrounding the ruins is a major tourist site with a functioning site museum. It has never been fully excavated and was very seriously damaged through the 20th century building of 400 military bunkers at one end of the site. Apollonia is currently receiving finding through the CHSED.

Other important sites are Butrint National Archeological Park, like Apollonia, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The Durres Amphitheater was built during the rule of Trajan and continued to function between the 2nd and 4th centuries CE. Kruje Castle is primarily a 15th century site, Berat castle is an older site but its current formation is primarily 13th century. These five sites are already supervised. Cultural heritage sites located close to Gjirokastër include the archaeological park of Antigone with a mosaic, columns, promenade, an antique scale, and the surrounding walls. The ancient theatre of Hadrianapolis is located near the village of Sofratika, approximately 14 km to the south-east of Gjirokastër. The 2nd C BCE Hadrianopolis amphitheatre has a capacity of 4,000 seats and has 27 steps.

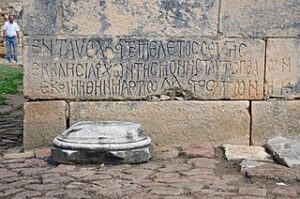

Antique stone built into the wall of St Mary Church, Pojan, Albania, Photo by Pasztilla aka Attila Terbócs, 20 September 2015, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

While the CHSED project – and hopefully others – may eventually place Albania in a position to provide Albanian cultural experiences to the United States through museum loans and exchanges, this is not yet even being considered. Albania’s government recognizes that it needs to focus on its own internal development needs. Therefore, while Albania welcomes foreign tourists and is reworking its museums to retune the historical narrative and replace the xenophobia of the Enver Hoxha period with a more welcoming attitude, Albania has not and will not likely engage in the sorts of cultural exchange with the U.S. envisioned under the CPIA for the foreseeable future.

Under the aegis of the State Department’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, import restrictions under the CPIA have provided for near permanent bans on the import of virtually all cultural items, from the prehistoric to the present time, from the countries which have sought agreements. If CPAC fails to heed the concerns of Congress regarding overbroad import restrictions unsubstantiated by clear evidence of meeting the four determinations, CPAC not only acts in derogation of U.S. law, but also lends support to what Congress feared, an exclusively statist rather than internationalist policy on cultural heritage.

Congress placed procedural and substantive constraints on the executive authority to impose import controls under the CPIA. Non-emergency restrictions may only be applied to archaeological artifacts of “cultural significance” “first discovered within” and “subject to the export control” of the requesting nation.[xvi] There must be some finding that the cultural patrimony of the requesting nation is in jeopardy.[xvii] The imposition of import restrictions must be part of a “concerted international response” “of similar restrictions” of other market nations, and can only be applied after less onerous “self-help” measures are tried.[xviii] Import restrictions must also be consistent with the general interest of the international community in the interchange of cultural property among nations for scientific, cultural, and educational purposes.[xix] Those are the requirements under the law.

Hand-colored Cabinet Card, Albanian Woman, Studio Marubi, Pjetër Marubi (1834-1903), private collection.

Albania has not provided evidence that the determinations required by the Cultural Property Implementation Act are met. The market for Albanian goods – if it exists at all – can only be a trickle of low value items offered in Europe and the U.S. without any showing that these were found in Albania specifically – or that they were looted – or even that they are authentic.

Mandatory statutory determinations must be based on evidence and facts, not speculation about imaginary markets and an ‘illicit’ goods traffic for which there isn’t evidence. Without having provided the facts substantiating the four determinations, Albania does not meet the criteria required by the Cultural Property Implementation Act to justify an MOU. It hardly needs repeating that every one of the statutory criteria must be met in order for the U.S. to implement import restrictions under the Cultural Property Implementation Act.

When the CPIA was passed, its goal was to facilitate a lawful trade that enriched U.S. cultural life and to block imports only of objects at immediate risk of looting which the requesting country, despite its best efforts, could not stop. Congress viewed the CPIA as balancing the United States’ academic, museum, business, and public interests by assisting art source countries to preserve archaeological resources while ensuring the U.S.’s continuing access to international art and antiques through a relatively free flow of art from around the world.[xx]

The Cultural Property Advisory Committee should apply a plain reading to the four determinations it must make. For the last 20 years, critics of the operation of CPAC by the Department of State (including a number of former members of CPAC) have argued that the agreements and import restrictions under the CPIA are overbroad and have disregarded the requirements of the law. Import restrictions should only be imposed in situations where the facts and the law support them.

The Committee for Cultural Policy and Global Heritage Alliance therefore respectfully request that Albania’s request for import restrictions be rejected, that the full text of the Albania request be supplied to the public, and that the public be given a meaningful opportunity to address the range of materials sought to be restricted and the chronological scope of the request.

Hellenic peninsula Greece Albania Bosnia and Bulgaria, Stefano Bonsignori, 1585, Google Art Project, public domain.

[i] The Committee for Cultural Policy (CCP) is an educational and policy research organization that supports the preservation and public appreciation of the art of ancient and indigenous cultures. CCP supports policies that enable the lawful collection, exhibition, and global circulation of artworks and preserve artifacts and archaeological sites through funding for site protection. CCP deplores the destruction of archaeological sites and monuments and encourage policies enabling safe harbor in international museums for at-risk objects from countries in crisis. CCP defends uncensored academic research and urges funding for museum development around the world. CCP believes that communication through artistic exchange is beneficial for international understanding and that the protection and preservation of art is the responsibility and duty of all humankind. The Committee for Cultural Policy, POB 4881, Santa Fe, NM 87502. www.culturalpropertynews.org, info@culturalpropertynews.org.

[ii] Global Heritage Alliance (GHA) advocates for policies that will restore balance in U.S. government policy in order to foster appreciation of ancient and indigenous cultures and the preservation of their artifacts for the education and enjoyment of the American public. GHA supports policies that facilitate lawful trade in cultural artifacts and promotes responsible collecting and stewardship of archaeological and ethnological objects. The Global Heritage Alliance. 1015 18lh Street. N.W. Suite 204, Washington, D.C. 20036. http://global-heritage.org/

[iii] Full Submission to Cultural Property Advisory Committee, Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, U.S. Department of State, on the Proposed Request for a Memorandum of Understanding Between the United States of America and the Republic of Albania.

[iv] This is the whole of the Public Summary.

[v] James F. Fitzpatrick, Falling Short – the Failures in the Administration of the 1983 Cultural Property Law, 2 ABA Sec. Int’l L. 24, 24 (Panel: International Trade in Ancient Art and Archeological Objects Spring Meeting, New York City, Apr. 15, 2010).

[vi] See Senate Report No. 564, 97th Cong., 2nd Sess. at 4 (1982)

[vii] See Senate Report No. 564, 97th Cong., 2nd Sess. at 6 (1982)

[viii] See results from: https://www.sothebys.com/en/search?query=albania&tab=objects

[ix] See results from: https://www.christies.com/lotfinder/searchresults.aspx?sc_lang=en&lid=1&searchFrom=searchresults&entry=albania&searchtype=p&action=paging&pg=all

[x] Please note when reviewing this data that in 2018, there were changes to the categories under which art imports were reported for U.S. entry specifically based upon the definitional language of the CPIA. Under the Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2018) Revision 6, Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes, “archaeological pieces” are now reported separately from “ethnographic pieces” and both of those are reported separately from “historical pieces.”

[xi] For the purposes of statistical reporting, number 9705.00.0075 “archaeological pieces” are objects of cultural significance that are at least 250 years old and are of a kind normally discovered as a result of scientific excavation, clandestine or accidental digging or exploration on land or under water.

For the purposes of statistical reporting, number 9705.00.0080, “ethnographic pieces”, which may also be called “ethnological pieces,” are objects that are the product of a tribal or nonindustrial society and are important to the cultural heritage of a people because of their distinctive characteristics, comparative rarity or their contribution to the knowledge of the origins, development or history of that people.

For statistical reporting of merchandise provided for in subheading 9705.00.00, collections made up of articles of more than one type of cultural property, i.e., zoological, biological, paleontological, archaeological, anatomical, etc., shall be reported by their separate components in the appropriate statistical reference numbers, as if separately entered.

Besides the former differentiation of gold and other, “Numismatic (collector’s) coins” are now separated by age as “250 years or more in age” and “other”. “Numismatic (collector’s) coins” are also now differentiated from coins that are “archaeological pieces.”

See Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Informed Compliance Publication on “Works of Art, Collector’s Pieces, Antiques, and Other Cultural Property.” https://www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/assets/documents/2020-Jun/Works%20of%20art%20etc%20ICP_0.pdf

[xii] European Commission, Candidate Countries and Potential Candidates, https://ec.europa.eu/environment/enlarg/candidates.htm, last accessed March 3, 2021.

[xiii] 19 U.S.C. § 2601

[xiv] See Council Regulation (EC) No 116/2009, available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32009R0116 (last visited September 8, 2020).

[xv] Culture and Heritage for Social and Economic Development Programme (CHSED), http://www.unesco.org/culture/pdf/mdgif/albania-fact-sheet.pdf

[xvi] 19 U.S.C § 2601

[xvii] Id. § 2602.

[xviii] Id.

[xix] Id.

[xx] 19 U.S.C. § 2602(a)(1)(A-D) and 19 U.S.C. § 2602(a)(4)

Edward Lear, Butrinto, Albania, 1861, Yale Center for British Art, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA.

Edward Lear, Butrinto, Albania, 1861, Yale Center for British Art, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA.