A nation’s cultural policy is usually framed and presented to the public as regulatory law intended to protect that nation’s particular history, identity, and traditions. Because of this conceptual justification for cultural property legislation, most people assume that such laws are limited to the regulation of archaeological excavations and the trade in ancient art. However, restrictions on the export of modern and even foreign cultural products also exist in many countries, often unbeknownst to foreign collectors of 19th and 20th century artworks.

Imagine Elena Quarestani’s surprise in 2015 when the Italian government blocked the sale of an artwork she owned by the Spanish artist Salvador Dali on the grounds that it was part of Italian cultural heritage. Our readers may also remember the seizure of Carlo Ponti and Sophia Loren’s artworks when they tried to move their collection from their Italian villa to Paris in 1977. To more and less restrictive degrees, not only developing nations, but also many Asian nations, EU countries such as Italy, and Russia and East European countries often have regulations on the export of any artwork more than 50 years old. And then there is Mexico… where 20th century artists have become, literally, monuments.

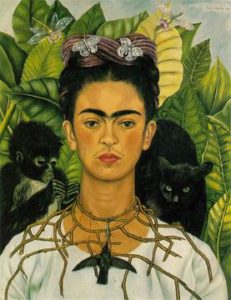

The record breaking sale of Diego Rivera’s The Rivals for $9.76 million at Christie’s in May of this year and the various protests against Mattel’s Frida Kahlo Barbie have brought Mexican cultural property laws into prominence in the news of late.

(For more on the Frida Kahlo Barbie see: Frida Kahlo Barbie Sparks Protests, Cultural Property News, March 14, 2018)

Jose Clemente Orozco, Mural “Catarsis” (1934) (detail) Mexico City. Palacio de Bellas Artes, photo by Wolfgang Sauber, [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html), CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0), Public domain or Public domain], from Wikimedia Commons.

The majority of these artists worked as propagandists for the Mexican revolution fought between 1910 and 1920. Other artists were granted this special legal status because of their depictions of Mexican landscapes or their contribution to a specific genre of art.

The decrees state that regulations on the nation’s modern artworks exist “for the purposes of duly protecting and preserving them” and in recognition of the artists’ contributions to Mexican national heritage. The artworks by individual artists, inclusive of any medium in which they might have worked, are named as monuments regardless of whether they belong to a government institution or are privately owned by an individual or organization in Mexico.

The owner must register them with the appropriate regulatory body, notify the government of any changes of ownership, protect them from harm, report any changes in condition, get approval from the appropriate regulatory body if they need repairs or restoration, and seek permission to reproduce any images of them. In addition, once they are decreed to be monuments, the works are prohibited from export except for government-approved, temporary purposes – such as museum exhibitions – and only after a bond for the works’ safe return has been posted with the Mexican federal treasury. This means that the artistic works that exist in Mexico, by any of these nine artists, must remain in Mexico even if purchased by a foreign buyer. Anyone attempting to illegally export a designated artwork can be subject to criminal prosecution for dealing in contraband.

José María Velasco , Cañada de Metlac (1893), Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico City,

[Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

“This painting is part of the National Heritage of Mexico and cannot be permanently exported from the country. Accordingly, it is offered for sale in New York from the catalogue and will not be available in New York for inspection or delivery. The painting will be released to the purchaser in Mexico in compliance with all local requirements. Prospective buyers may contact Sotheby’s representatives in Mexico City and Monterrey for an appointment to view the work.”

Though there is considerable overlap in the restrictions and regulations for artists’ works considered artistic or historic monuments, the two designations are regulated under two different regulatory agencies: The National Institute of Fine Arts (INBA) regulates Artistic Monuments, and the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) regulates Historic Monuments.

Artists Who Are Also ‘Monuments’

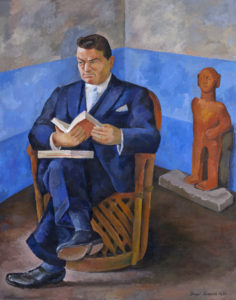

Portrait of John Dunbar, 1931, The Bernard and Edith Lewin Collection of Mexican Art, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Reproduction of Diego Rivera governed by Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

The majority of the artists whose works are now Artistic or Historic Monuments were instrumental in conveying the ideology of the Mexican revolution to a largely illiterate population, primarily in the form of murals. Their work was a continuation of Mexico’s long artistic tradition of using mural painting to communicate ideas and doctrine. The revolution had been controversial and a part of a very bloody civil war. The winners wanted to glorify the idea of a “mestizo” nation, one where indigenous peoples and the working class were promoted alongside the Spanish.

There were many artists who contributed to this public education project but the three most influential were José Clemente Orozco and Diego Rivera, whose works became National Monuments in 1959, and David Alfaro Siqueiros, whose works became Artistic Monuments in 1980.

Known as Los tres grandes (the great three), Orozco, Rivera and Siqueiros painted fantastical murals showing the demise of the old order and the rise of an egalitarian society led by the working class.

Despite their promotion of the peasantry, the laboring classes, and Marxist values, works by these three artists can sell today for millions of dollars. In 2010 one of Orozco’s paintings sold for $1.14 million at Christie’s. Earlier this year Diego Rivera’s The Rivals sold for $9.76 million, the most a work by a Latin American artist had ever sold for at auction.

In many ways it was the work of Gerardo Murillo Coronado aka “Dr. Atl,” and Saturnino Herran, that gave rise to the political school of the Mexican muralist tradition. In 1906 Dr. Atl had written a manifesto promoting the idea of a public art movement that “would speak to the interests and realities of the Mexican people.” This manifesto is credited as the inspiration for the Mexican Mural Movement that spread the revolution’s ideals and helped Mexico to develop its modern national identity. This artistic movement took place much earlier than Russian Socialist Realism, which it resembled both politically and formally.

Diego Rivera, Detroit Industry, Diego Rivera murals at the Detroit Institute of Arts.

In the 1988 decree declaring Saturnino Herran’s works to be an Artistic Monument, United Mexican States president Miguel De La Madrid H. acknowledged the dual importance of Herran’s art to Mexico’s political and artistic history. He emphasized the artist’s “permanent concern for appreciating the social and ethnic elements that make up our national identity,” and argued that “the aesthetic qualities present in the works of this artist [are] characterized by a genuine nationalistic posture, a revolutionary aim based upon his clear vision of the conditions of his historical moment and by a will to help in developing Mexican culture.”

It was for these reasons, President de la Madrid explained, that Herran’s works were to receive special legal protections, “in order to make possible its conservation as an expression that constantly affirms our national identity and which puts forth Mexican culture.”

Though Saturnino Herran passed away in 1918, before the revolution ended, he was known to promote and portray the inherent beauty and dignity of the Mexican people, as he saw them, in an art movement called ‘indigenismo’. For the Centennial Anniversary of Independence from Spain he worked with Jose Orozco to form the Society of Mexican Painters and Sculptors to stage a counter-exhibition of purely Mexican art.

Frida Kahlo, Self Portrait, Frida Kahlo Foundation.

Like Herran, Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera (whose careers are far too well-documented, to need further explanation here) have achieved fame as much for their contributions to Mexico’s modern cultural and political identity as for their own work. All of Kahlo’s artworks, as well as her “easel, graphic works, engravings and technical documents” were declared National Monuments on July 11, 1984.

Artworks of a patriotic nature, or which expressed Mexico’s national identity, could also gain an artist’s legacy formal recognition and legal regulation. This was the case for the first artworks to be decreed National Monuments: those of Jose Maria Velasco, in 1942. He was most known for his landscape paintings, particularly his seven renderings of El valle de México, which made “Mexican geography a symbol of national identity.”

The decrees for Remedios Varo Uranga and Maria Izquierdo – whose works were declared Artistic Monuments in 2001 and 2002 respectively – begin with the same sentence:

“The creation of Mexico’s artistic heritage is a part of the historical process in which society has an essential role regarding the reaffirmation of cultural expression, when the latter are worthy and meaningful for said society, a reason for which the Nation’s artistic heritage must include the dynamic and ever-changing universe of art, preserving and actively using the assets that constitute Mexico’s cultural wealth.”

Diego Rivera declared Maria Izquierdo’s work some of the best at the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes (Academy of Fine Arts) when she was a student, and praised her early work as a professional artist. Later in her career he would have a change of heart and proclaim, along with the other Tres Grandes, that she lacked talent and expertise. In response to his criticism, Izquierdo said, “it is a crime to be born a woman and have talent.”

Maria Izquierdo, Mi tía, un amiguito y yo, 1942.

In 1930 she became the first Mexican woman to have a solo exhibition in the United States. Later her work would also be shown in Paris and South America – all accomplishments recognized in the Mexican government’s decree along with her promotion of Mexican identity.

The identification of Remedios Varo Uranga’s artworks as Artistic Monuments shows a distinct shift in official notions of what kind of work should constitute a national monument. Remedios Varo was not from Mexico, but of Spanish origin, and her work was not in a traditional, uniquely Mexican school or style. She was a Surrealist painter, part of an international surrealist movement. Artistically, there was nothing to tie her to the nationalist art tradition, unlike Mexico’s other recognized artists. However, Mexico has identified 38 of her works produced in and loaned to Mexico as Artistic Monuments and relevant to the history of Mexican art. The decree acknowledges the seeming disparities between Varo’s oeuvre and that of other protected artists, and at the same time recognizes her as one of Mexico’s own.

Remedios Vari, Photo By Quinn Comendant [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

“Remedios Varo Uranga (1908-1963) freely chose Mexico as her country, her fatherland and home in order to consolidate her personal and artistic life. Mexico welcomed the artist within its cosmopolitan culture, as one of a generation of artists which enriched Mexican culture with the vitality of their pictorial talent and the introspective sensitivity of her own inner world, which reflects the conditions of peace and well-being that Mexico offered to her in order to attain the free expression of her ideas and the expression of her creative spirit. Remedios Varo’s artistic career was consolidated in Mexico and her Mexican work is what has earned her growing prestige and recognition in the history of Universal art and she represents the artistic pluralism existing in our country before the rest of the nations of the world. The artistic work of Remedios Varo is a fundamental part of the history of twentieth century Mexican art, since its aesthetic message evidences the ability of Mexican culture to establish a dialog and integrate itself with the rest of the cultures of the West, which the artist absorbed during her early formation in Europe.”

Impact of Mexico’s Monument Laws on the Market

It’s difficult to say at present what the full impact of Mexico’s monument decrees will be on the international circulation of art and the art market. Eileen Kinsella, writing for artnet news in her article Frida Kahlo Market Booming Despite Tough Mexican Export Restrictions, says that for Kahlo, at least, short supply may be fueling demand. Because Kahlo’s works within Mexico cannot be exported, those already on the market outside the country are more in demand than before. Kinsella quotes New York art dealer Mary-Anne Martin, who founded the Latin American art department at Sotheby’s: “the tight export law “really does have an effect of creating two markets—one outside Mexico and one within.” The same painting that might sell for $500,000 in Mexico could easily double that outside because of international demand.” Whether Mexican buyers are willing to pay international prices or whether international buyers are willing to own works which cannot leave Mexico is a huge question for the future.

Some Consequences of Government Control

Detail of mural by José Clemente Orozco at Baker Library, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire. October 2005, Wikimedia Commons.

The broader, more philosophical implications of Mexico’s cultural policy are harder to tease out. By deciding to indefinitely retain and regulate certain artworks within its borders, Mexico sets an example for other nations of how they might secure their own cultural heritage within their borders for future generations. The program places an implicit value upon art, and artists, recognizing their importance to the nation and helping to preserving their memory.

Yet a government-directed program intended to enshrine certain artists in the canon of Mexico’s cultural heritage could also produce a biased picture of Mexican art, culture, and identity. Any system that honors certain artists must occlude others, narrowing the public understanding of what is, and is not, a part of their nation’s heritage. The inclusion of Remedios Varo Uranga in the list of Artistic Monuments indicates that Mexican protections may extend to embrace many different facets of its artistic history, but it also expands the scope of government control over how Mexico’s culture and history are defined.

Residents of Mexico will not necessarily benefit from the laws in any concrete way. These laws only impede the movement of art across borders; they do not render the artworks in private collections in Mexico any more accessible to the Mexican people than they are now. It may be that private collectors will be inspired by their works’ new status as “Artistic Monuments” to donate or lend them to museums. It may not.

The only certain consequence of Mexico’s regulatory legislation is to dramatically narrow the number and variety of Mexican artworks available for sale, exhibition, and study abroad. The restrictions on art exports will limit access to Mexican art for the citizens of other countries interested in Mexican culture and history, as well as for people of Mexican descent living abroad, who want to connect with their families’ heritage.

The need to obtain government permissions and to put down a monetary bond for works to leave the country means that scholars hoping to study the works of Izquierdo, Varo, or Kahlo have fewer hopes that traveling exhibitions will bring works to them. Unless they have the funds to visit Mexico, scholars will have to content themselves with studying photographs of the works. That is, if the Mexican government permits photographs be made available in the first place. It is in their power to refuse or limit this access, to prevent even the images of a “monument” from leaving the country – and that is an ominous notion.

A view of the main stairwell with paintings by Jose Clemente Orozco in San Ildefonso College in the historic center of Mexico City, Self-published work by Thelmadatter) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons.

A view of the main stairwell with paintings by Jose Clemente Orozco in San Ildefonso College in the historic center of Mexico City, Self-published work by Thelmadatter) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons.