There have been new developments in the ongoing negotiations between a group of British museums and the African nations which claim ownership of artworks in their collections. Recent efforts by British museums to improve relations with their African counterparts have hit a speed bump.

Last month, London’s Victoria & Albert Museum opened a new exhibition, Maqdala 1868, highlighting a group of extraordinary Ethiopian artworks which have been in the museum’s collection for nearly 150 years. These treasures, formerly the properties of the Ethiopian monarchy and church, were seized by victorious British soldiers after the siege of Maqdala in 1868. (For more on the Maqdala treasures, and on the Europe-wide coalition of museums reconsidering the status of their African artworks, see “Returning African Heritage From Global Museums,” Cultural Property News, April 14, 2018.)

The new exhibition explores the tragic history of the artifacts, and the political fallout of the siege and seizure.

At the exhibition opening, V&A Director Tristram Hunt committed himself to arranging for some or all of the artworks to travel back to Ethiopia on long term loans, and expressed the hope this project might be the first in a series of art exchanges between the two nations. At the time, Hailemichael Afework Aberra, Ethiopia’s ambassador to the UK, seemed pleased with the proposal and spoke positively about the V&A display and its intentions.

Antique views from foreign perspective. Anonymous Portuguese illustration from the 16th century codex known as the Códice Casanatense, depicting Ethiopian people. The inscription reads: “Abyssinians that inhabit the straits of Mecca (the Red Sea) on the side of Ethiopia, circa 1540. Wikimedia Commons.

Despite its former apparent enthusiasm for the V&A’s proposed program, the Ethiopian government has recently changed its position – or perhaps clarified what their stance has been all along. In an interview with The Art Newspaper, Ambassador Aberra stated that “My government is not interested in loans, it is interested in having those objects returned.” The change in position may reflect a change in the Ethiopian government itself, a new prime minister having assumed his post just four days before the V&A exhibition opened.

Unfortunately, the request for full restitution, and the Ethiopian insistence on their claim to the objects, may mean that the artworks will not leave the V&A at all. None of the museums currently in possession of disputed Ethiopian artifacts, which include the British Museum and the British Library as well as the V&A, have the right under their charters to deaccession the artifacts, even if they decided that was the right course. Though the objects are under the protection of these institutions, at the same time they are legally the property of the British nation, and authorities have hitherto been unwilling to surrender title to the objects.

(The case of the Maqdala treasures is an unusual one – in which a 21st century government is less interested in reparations than it was in the nineteenth century. In large part this is because the removal was an example of violent pillage, instead of the more typical cultural property dispute, in which a nation comes forward with claims 50-100 years after the fact, based upon a national ownership claim that was not valid many years before. When the Maqdala objects first arrived in England, then-Prime Minister William Gladstone expressed deep regret that they had been seized, and advised that they be returned to Ethiopia as soon as possible.)

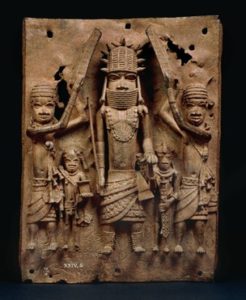

Benin Plaque, Bronze, Af1898,0115.38, © The Trustees of the British Museum

Because the Ethiopian government considers full restitution of the Maqdala treasures the only equitable solution, the British are understandably anxious that any objects which might leave the UK on a long-term loan would never come back. The interests of the British public, which includes a substantial Anglo-Ethiopian community, as well as the political difficulty of transferring title to the artifacts, may significantly delay or even terminate the museums’ hoped-for loan program.

The British Museum is currently working towards implementing another long-term loan program, this one involving a large group of Benin bronzes seized by British soldiers in 1897. The Nigerian government and the Benin royal family have both requested the bronzes return several times in the past. Now, a coalition of nine museums in the UK and Europe is working towards a massive program of loans to Nigeria of artworks and artefacts taken from the region in the nineteenth century.

In anticipation of this loan, Nigeria is in the process of building a new, state of the art museum in Benin City. It remains to be seen whether Ethiopia’s changed position will put pressure on Nigeria to request full restitution of its treasures, rather than to pursue long-term loans.

The Collection - Treasury Of The Chapel Of The Tablet, Aksum, Ethiopia, October 30, 2007, By A. Davey from Where I Live Now: Pacific Northwest [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons.

The Collection - Treasury Of The Chapel Of The Tablet, Aksum, Ethiopia, October 30, 2007, By A. Davey from Where I Live Now: Pacific Northwest [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons.