In November of 2017, French President Emmanuel Macron made a dramatic speech about the future of African art in France’s public collections. Before an audience at the University of Ouagadougou in Burkina Faso, Macron said that “in the next five years, I want the conditions to be met for the temporary or permanent restitution of African heritage to Africa. This will be one of my priorities.”

Macron’s statement represents a remarkable change from past French policy on the restitution of cultural property to nations now seeking returns. French patrimonial protections began with the 1566 Edict of Moulins, which affirmed that the property of the French crown is inalienable. That inalienability has been translated to the holdings of the French Republic, including the contents of public museum collections. As recently as March of 2017, the French government categorically refused a request co-signed by lawmakers in Benin and France for the restitution of cultural property taken from the Benin region by France in the colonial period.

According to the V&A exhibition didactic, “William Gladstone condemned the taking of treasures from Maqdala… and ‘deeply lamented, for the sake of the country, and for the sake of all concerned, that these articles … were thought fit to be brought away by a British army.’ He urged that they ‘be held only until they could be restored.’” Victoria and Albert Museum.

Macron’s determination to “prioritize” restoring African art is not a complete reversal of French policies, however. It is significant that his proposal was for the “temporary or permanent restitution of African heritage,” and that he affirmed the importance of African art’s ongoing presence in European museums as well as African ones: “African heritage must be highlighted in Paris, but also in Dakar, in Lagos, in Cotonou.” It is likely that what Macron has in mind is not a wholesale restitution of all the African artifacts in French collections, but perhaps a limited number of outright returns, in order to facilitate a broader program of long-term loans and exchanges with African museums. There are tens of thousands of African objects in France’s national museums, and it does not appear that Macron believes it feasible or even desirable for many to make the trip back to their countries of origin.

The timing of Macron’s proposals is felicitous: across the Channel, several British museums with collections of African art are currently considering similar long-term loan and gifting programs. These programs, like Macron’s idea, are inspired by two separate, but not necessarily conflicting goals: to do justice to the African communities and nations whose heritage was seized by European forces in the colonial period, and to continue the work of educating their audiences about the history and artistic achievements of African peoples.

One of London’s great Victorian institutions, the Victoria & Albert Museum, is now confronting the dubious origins of some of its African treasures.

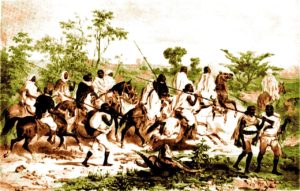

Early 19th century warriors, Abyssinia, From T. Lefebvre and others, Voyage en Abyssinie (Paris 1845-49).

The Victoria & Albert Museum, commonly known as the V&A, is dedicated to the decorative arts. Its galleries house examples of fine work in metal, textiles, wood, and every other medium imaginable. The V&A began as both a museum and an art school, its global collection formed for the purpose of educating British artists and craftspeople in good design. Today, the V&A is one of London’s best-beloved arts institutions, and a venue for exhibitions ranging from 19th century Indian decorative art to Alexander McQueen’s designer fashion.

Though many of the collection’s highlights were given or lent to the museum by their source countries, and others purchased on the open market, some were seized by force. A new display at the V&A , Maqdala 1868, illuminates the sad history of artifacts taken from Ethiopia in 1868. The objects seized by British troops included gold and silver regalia and vessels, once presented to the Ethiopian Orthodox church by the Emperors of Ethiopia, hundreds of manuscripts, and other precious goods taken from the Ethiopian monarchs.

The new exhibition delves deeply into their history. The occasion for the seizure of these remarkable objects was the Battle of Maqdala, a significant victory for British troops over Ethiopia’s army. In the aftermath of the battle, Emperor Tewodros II committed suicide, and his fortress was raided – the V&A’s artifacts were among those seized from Maqdala.

Dèjatch Alámayou & Básha Félika (Captain Speedy), photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron, July 1868, Isle of Wight, Britain. Museum no. RPS.707-2017. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

The V&A has dug into its own archives for this new gallery arrangement, finding materials which give both a personal and political context for the artifacts. Other objects at the museum include jewelry and a dress which belonged to the Ethiopian Queen Terunesh at the time of her death from illness, just one month after the battle. After the death of Queen Terunesh, the orphaned Prince Alemayehu was brought to England. Among the artworks on display at the V&A is a photograph of Alemayehu with a British officer, Captain Tristram Charles Sawyer Speedy, taken on the Isle of Wight by Julia Margaret Cameron, best known for her photographic portraits of Tennyson, Carlyle, and Charles Darwin. Some of the art taken after Maqdala can be seen in the photograph.

In the recent past, the Ethiopian treasures have been part of the V&A’s “Sacred Silver,” galleries, an area focused on the use of precious materials in religious rites and sacred spaces. Now set apart in a dedicated display, the artifacts tell another story: of historic conquest and modern diplomacy. Along with its historical content, the V&A display features commentary on the art and its origins from members of London’s Ethiopian community. The exhibition itself was developed in consultation with the Ethiopian Heritage Fund (based in Herefordshire), the Anglo-Ethiopian Society, and members of the Orthodox Tewahedo Church. Ambassador Hailemichael Aberra Afework and Ethiopia’s minister of culture and tourism, Hirut Woldemariam both attended the opening of the display on April 5th.

Despite the pleased response to the V&A’s special exhibition by Anglo-Ethiopian communities and representatives of the Ethiopian government, the artifacts on display may not remain in England.

Ethiopian Crown, collection of the National Museum, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 22 October 2007. Author A. Davey. Wikimedia Commons.

In 2007, restitution claims signed by then-president Girma Wolde-Giorgis were submitted to the British government, requesting the return of all of the seized Ethiopian artifacts in public collections. Those claims are still awaiting a response. In the interim, V&A curators are in negotiations to dispatch many of the Ethiopian materials to their country of origin on a long-term loan. Tristram Hunt, director of the V&A, has said that there are no plans to restore the objects to Ethiopia permanently. Instead, he hopes that this loan, a potential British-funded grant to Ethiopian museums, and conversations between British and Ethiopian curators, will lead to a closer relationship between the arts institutions of the two countries.

The British Museum also has treasures seized at Maqdala in its holdings, some of which have never been on display, due to their status as sacred objects. They cannot even be viewed by visiting scholars without prior permission from the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. Other less sensitive materials have been on view at the museum for many years. The British Museum, like the V&A, has stated that it is not planning on returning its Ethiopian objects, but is considering a similar long-term loan program.

Art and artifacts now at the British Museum will also be traveling back to their origin countries. The British Museum program is actually part of an international project to pursue a broader goal of redistributing African art from European collections. The British Museum is currently conferring with other institutions around the UK and on the European continent, and with counterparts in Nigeria and Benin, about a new program of art loans and exchanges. Their aim is to return on long-term loan some of the many works of art taken from the former Benin kingdom in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Stone statue from Addi-Galamo, Tigray Province (northern Ethiopia), 6th – 5th century BCE, from the National Museum, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Author A. Davey. Wikimedia Commons.

Guaranteeing that the objects will not be permanently seized by the Nigerian government on their arrival in the country is one among the many issues that will need to be resolved before the art can travel. The museums’ directors have undertaken this restitution project because they recognize the need to repair the damage done by colonialism, but their efforts are complicated by their obligation to serve the local and global community of scholars and art lovers who rely upon these resources being more widely. The value to Nigeria and Benin of having their history and their culture represented in museums abroad is also an important consideration for the negotiators.

Speaking to The Guardian, John Picton, formerly the curator of the National Museum in Lagos, summed up the issue at hand: “The moral case is indisputable. Those antiquities were lifted from Benin City and you can argue that they ought to go back. On the other hand, the rival story is that it is part of world art history and you do not want to take away African antiquity from somewhere like the museums in Paris or London, because that leaves Africa without its proper record of antiquity.”

The ongoing negotiations between African and European museums and leaders are an extension of the diplomatic work done by the artifacts themselves. These nations, once hostile combatants, are now able to engage in talks at the highest levels, even sending their executives on visits. The African artifacts once seized as booty or curiosities by colonial troops are now treasured and respected not just by the descendants of their original owners, but by the institutions in host nations, as well. Artworks can be both effective teachers of cultural understanding and symbols of identity. Nigerian, Ethiopian, and Beninese communities in London and Paris benefit from access to their cultural heritage, just as much as other citizens benefit from the learning opportunities these artifacts offer. Restitution and loan programs such as those proposed by Macron, which balance justice for African cultural property claims against the need for international access to art, are a positive step forward.

Musée du Congo, Tervuren, Belgium: one of five interior scenes. Collotype.

Musée du Congo, Tervuren, Belgium: one of five interior scenes. Collotype.