Qtub Minar, Delhi, India, Detail, photo by Diego Delso, 10 December 2009, license CC BY-SA.

Download PDF Full 2024 India Report

A Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with India under the Convention on Cultural Property Implementation Act[1] (CPIA) appears to be a done deal. A full year before India’s ‘request’ was heard before the Cultural Property Advisory Committee (CPAC) at the State Department – which is supposed to be the first step of a recommendation to the President – the Indian press had announced that India’s government was finalizing the terms of an agreement to block the entry of Indian art and antiquities into the U.S. The first the American public heard about a future agreement with India was a November 29, 2023 announcement on a State Department website that a public hearing on the request was scheduled before CPAC in January of 2024.[2] Information on the objects India wanted blocked was added to the website in mid-January 2024, only a week before the deadline for written testimony from the public.[3]

India sought the following:

“[I]mport restrictions on archaeological and ethnological materials dating from 1.7 million years ago to 100 years ago, including objects dating from the Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic, Ancient Periods (including, but not limited to, the Indus Valley Civilization, Maurayan Empire, Shunga Empire, Gandharan Kingdom, Gupta Period, and the Gurjara-Pratihara, Rastrakuta, and Pala Dynasties), and Historic Periods (including, but not limited to, the Chola Dynasty, Delhi Sultanate, Mughal Empire, and the British Raj). Categories of objects include stone tools and artifacts, terracotta figurines, toys, coins and medals, seals and sealing, molds, dies, sculpture, utensils, architectural materials, arms and ammunition, scientific instruments, and jewelry and toiletries. Protection is also sought for miniature paintings, art pieces in cloth and paper, and manuscripts dating from the 7th century CE to 75 years ago.”[4]

A scenic view from Daulatabad Fort, photo by Anand Saurkar, 14 May 2017, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

This Commentary reflects on the scope of India’s request and analyses the status of heritage protection in India. Our sources include reports from the office of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India, Indian laws and court cases, official statements and public records from India’s Ministry of Culture and the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) and Indian press reports.[5] Our conclusion, that an agreement between the United States and the Government of India is not merited, is based on the Indian government’s own admissions of decades of negligence, underfunding, and failure to follow its own laws.

Despite India’s failure to meet the criteria set by Congress in the 1983 Cultural Property Implementation Act (CPIA), we fully expect that the State Department’s diplomatic goals will once again supersede both the law’s requirements and Congress’s intent. An agreement with India that places U.S. art interests at risk is inevitable under the aggressive pursuit of cultural heritage MOUs by the Department of State’s Cultural Heritage Center at the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs.

Foundational Principles: What Is an Agreement Under the Cultural Property Implementation Act?

The CPIA provided for the U.S. to enter into agreements with foreign nations to temporarily restrict the import of “significant” cultural items as a response to current looting. Restrictions are also allowed under the CPIA to prevent the importation of ethnographic objects “important to the cultural heritage of a people because of its distinctive characteristics, comparative rarity, or its contribution to the knowledge of the origins, development, or history of that people,” which Congress limited to the products of tribal or non-industrial societies.[6] MOUs are accompanied by Designated Lists of objects at risk that may be restricted from import into the U.S.

The Prime Minister, Shri Narendra Modi being presented the ‘Chhau Mask’ as memento.

An agreement under the CPIA is intended to work in concert with similar efforts on the part of other nations.[7] The CPIA also obliges source country governments to take self-help measures consistent with the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property (the “1970 UNESCO Convention”), for example, protecting archaeological sites and curbing markets for looted objects in their own countries.[8] An agreement must be in the interest of the lawful international circulation of art for cultural, educational and scientific purposes.[9] The role of the CPAC committee is to review requests made by source nations for an MOU and to identify covered objects to be subject to import restrictions. Congress granted CPAC the ability to make recommendations for five-year-long import restrictions that are renewable at need, but only in circumstances in which all four criteria under the CPIA continue to be met.[10]

Thus, CPAC’s task is to review the Government of India’s request and determine:

- whether there is a current looting situation that jeopardizes the cultural patrimony of India,

- whether India has taken measures consistent with the 1970 UNESCO Convention to preserve national cultural property,

- whether a MOU would be “of substantial benefit in deterring looting” and if another less drastic solution than import restrictions is available, and

- whether import restrictions are justified under the legal requirement that they be “in the general interest of the international community in interchange of cultural property among nations for scientific, cultural, and educational purposes.”

India’s History of Cultural Property Law and Management

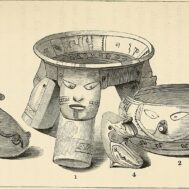

Figure of a nobleman, Mohenjo-daro excavations, pre-Partition India, present-day Pakistan, photographer unknown. Private collection.

India’s cultural heritage spans 5000 years, several major civilizations, multiple empires, and thousands of small kingdoms. India is so rich in archaeological sites that it is literally layered with evidence of the rise and fall of civilizations, religions, and peoples. Never united into a single polity until the British colonial period, the idea of a consolidated Indian nation is an entirely modern concept. The fact that there was no single Indian ‘nation’ prior to the colonial period meant that the foundations of Indian identity as a people with common interests, despite religious, social, and economic differences, drew on predominantly Western concepts of nationhood.

The great Indian scholar and art historian, Dr. Pratapaditya Pal,[11] in a recent interview[12], identified a number of historical and factual inconsistencies in India’s request that complicate and in some ways render impossible the enforcement of the import restrictions requested by India:

“It should be remembered that the subcontinent today is divided into three distinct nations: India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. Hence, it is necessary to determine whether the object came out of the geographical regions which today constitute the nations known as India, Pakistan or Bangladesh, which can be daunting for non-specialists. Even the so-called scholars and archaeologists lack the knowledge.

Moreover, it must be remembered that while the subcontinent known as “India” during the historical period, which begins no earlier than about roughly 300 B.C. was the recipient of cultural objects from abroad by both land and sea routes from both east and west and objects manufactured in India, especially textiles and religious objects were legitimately exported by other countries and nations. As example, I cite the Indian carved ivories that were found in Italy, primarily in Pompeii and now in Naples. Similarly, after Buddhism, which originated and was exported from the subcontinent as far east as Japan and west as Egypt, numerous religious objects traveled with merchants and pilgrims from India across Asia and as far west as Europe. …

India’s definition of “Archaeological and Ethnological” cultural property is not only inadequate but absurd. To cite only one instance, the Indus Valley Civilization flourished between both India and Pakistan, but the two most important sites in fact are in Pakistan. Therefore, this is so vague that it is impossible for either U.S. customs, or archaeologists and ethnologists, in either India or the USA, to distinguish what was made where.

Besides, during the Indus Valley Civilization spanning from 2500 to 1500 BC, there was no nation called India or Pakistan. In fact, the name of the country (or people) where the civilization flourished was likely “Melhuah.” What then happens of the period between 1500 BC, the putative end of the period of the Indus Valley Civilization and the beginning of the Maurya period after Alexander’s invasion and conquest in the 4th century BCE and the subsequent cultural material produced by his successors, all of which are now well beyond the Indian borders, either in Pakistan or in Afghanistan in an ancient region called Bactria? Can they be claimed by India?

Similarly, the term “Gandhara Kingdom” makes no sense and is also beyond the jurisdiction of India—a nation created only in 1947. Most Gandhara material in Europe and America collections cannot be claimed by today’s Indian nation as they originated in Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Another glaring error is in the case of the division of the state of Bengal in the east of the subcontinent first into East Pakistan and subsequently into Bangladesh. In the so-called Pala Period (8th – 12th centuries) a dynasty named Pala ruled over both regions. To determine what was made in West Bengal and Bangladesh can be very tricky even for specialists. Is it fair to expect US Customs officers to be able to tell the difference and make a sensible decision?”[13]

Dr. Pal has identified several key issues above – the extensive and open trade of many centuries, long before the existence of an “Indian” nation, and the inability of even specialists to correctly identify the source of objects made within the vast region of the Indian subcontinent. Dr. Pal’s writings have also made clear that the history of India and its variable and changing laws, and the fact that most of what India’s request calls its ‘national cultural property’ were treated as trade goods, not inalienable objects, would render this request an impossibility to administer.

Indian trade cloth, cotton 14th-16th century, found in Southeast Asia, Asian Civilizations Museum, Singapore.

India’s potential for trade, not a desire for conquest, is what brought European powers to the subcontinent in the first place. This trade was not simply from India to the West and vice versa. To simplify matters greatly, the spice trade in Southeast Asia had been dominated by Arabs for centuries, and to bring it under European control required that European traders be able to supply the goods that Southeast Asian sellers wanted and valued – primarily India’s beautifully dyed and printed cotton fabrics. Along with supplying European markets, British control of Indian textile manufacturing was imperative for the British to control the spice trade. Indian cotton cloths, dating as far back as the 12th and 13th centuries, which are sometimes depicted as worn by gods and kings on ancient stone carvings from Thailand, Cambodia, and the Indonesian islands, can still be found, preserved and reverenced, in Spice Island communities in the Far East. 12th to 17th century Indian printed cloths as well as bronze and brass statues have also been found in ancient shrines and monasteries in Tibet and China. Virtually all the objects named on the proposed Designated List for India were made for trade as much or more than for domestic use. Is it the intent of the CPIA to reverse the trade of centuries, even millennia, and claw back trade goods made between 75 and 2000 years ago?

India’s Earliest Heritage Laws – Protecting Buildings and Monuments

It is well-known that the establishment of a unified British Indian administration and legal structure came only after protracted conflicts between local rulers and among colonial forces representing several European powers. The development of a vast trading economy under the British East India Company resulted in India’s first unified economic and political administration. India’s first modern cultural administrative apparatus was also shaped by British traditions.

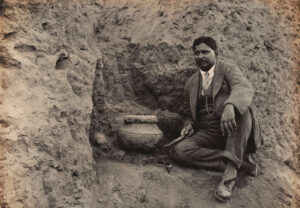

Indian archaeologist R.D. Banerji excavating at Harappa. Private collection.

The earliest Indian laws related to cultural heritage were passed in Bengal in 1810 and 1817. These laws ordered the protection of historic, publicly owned buildings as “monuments.” The first sweeping colonial Indian laws on cultural heritage paralleled the archaeological research conducted by British academics and amateur historians. Buildings of historical interest, even if privately owned, were protected by statute in 1863. The same year, the Religious Endowments Act invested British government officials with powers of adjudication over properties owned by Muslim trust organizations, waqfs,[14] but decisions by colonial courts attempted to follow existing interpretations of Islamic law. The Indian Treasure Trove Act of 1878 was modeled on British domestic laws granting “found” objects of precious metal to the Crown, but in the case of Indian treasure, treasure was granted to the colonial administration. India’s prehistoric cultures, its earliest civilizations, and even its Buddhist past came to light largely during the colonial period as a result of British interest: this research developed through both official and independent scholarly investigations by British and Indian scholars of the highest caliber.

Documenting India’s Heritage: the Archaeological Survey of India

The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) was founded in 1861, and the National Archives of India (NAI) were first established as the Imperial Records Department in 1891. The ASI and NAI were tasked with archaeological excavation, academic research, preservation of India’s monuments and cultural objects, and curation of historical records. Both agencies now form part of India’s Ministry of Culture. Even today, the ASI and Cultural Ministry retain administrative structures that date to the colonial period.

The ASI was originally focused on supervising excavations of ancient Buddhist sites, and on epigraphical and scholarly studies illuminating this forgotten period of Indian history. By 1904, a well-established ASI supervised a general Ancient Monuments Preservation Act that placed preservation and control in government hands. In the early 20th century, under Director John Marshall, the ASI uncovered the archaeological remains of the ancient Indus Valley Civilization at Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro.

From the 1930s, both Indian and British Directors led the ASI at various times, and numerous important archaeological discoveries were made under their leadership. Partition, which followed independence, left almost all the great Muslim monuments of the Indian subcontinent in present day India, not Pakistan or Bangladesh.

Excavations at Harappa. Private collection.

Although forts and government buildings of political and historical importance were included among protected monuments, the vast majority of structures defined as ‘monuments’ under colonial and later Indian national laws were associated with religious communities: shrines, temples, tombs, cemeteries, and mosques. Nonetheless, the legal frameworks protecting Indian monuments from the colonial period onwards were essentially secular and the approach to conservation of historic sites was based upon consciously impartial scientific procedures. Older sites deemed remnants of past religions, including Buddhist, Jain and Hindu structures that were no longer in community use, were managed by the secular state, whereas those held under waqf or trust endowments were deemed to belong to the communities that used them for religious activities. This policy was generally understood as separating the state from current religious matters and ensuring that communal tensions between religious communities would not “distort the unity of the country.”[15]

Early 20th century cultural heritage policies also accepted that many ‘monuments’ would require an adaptive approach to preservation that accommodated continuing religious usage. The Indian Archaeological Policy, 1915:18-9, states in clause 19 that:

“…there are frequently valid reasons for restoring to more extensive measures of repair than would be desirable, if the buildings in question were maintained merely as antiquarian relics… [T]he object which Government set before themselves is not to reproduce what has been defaced or destroyed, but to save what is left from further injury or decay, and to preserve it as a national heirloom for posterity.”[16]

India held so many sites classified as monuments that only a few could be considered appropriate for preservation. The Conservation Manual of 1923 defined three categories of ancient monuments:

- monuments whose present condition or historical or archaeological values merited maintenance in permanent good repair,

- monuments desirable to save from further decay by basic measures such as removing groundwater or vegetation, and

- monuments whose comparative unimportance or damaged state did not merit conservation.[17]

Only monuments in the first category were listed as ‘protected monuments.’ Responsibility for these protected monuments could lie with the state, with waqf organizations or private persons, or under combined management.

Distinguished archaeologist K.N. Dikshit, center, at a meeting of the Numismatic Society of India, 1938. Photo source Harappa.com.

After independence, new Indian cultural heritage laws and regulations, such as the 1958 Ancient and Historical Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act, effectively reiterated colonial period legal protections. Conservation policies under the ASI followed the Indian Constitution’s explicit secularism. Official heritage policies often passed over community religious interests in less famous Indo-Islamic monuments. In addition, the continued existence of religious endowments, waqfs, provided an alternative source of funding for the preservation of buildings used for Muslim worship. The 1958 Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act gave India’s Union government the power to select and remove monuments having national importance, to acquire historic buildings for preservation, and to “decide the religious identity of a monument of national importance and the nature of religious observance inside it.”[18]

On achieving independence in 1947, laws governing exports continued to follow secular lines. The new Indian government took official control of exports of art and antiquities in the Antiquities Export Control Act. A few museums were established as national or state-level governmental entities, but most were tied to specific historical monuments or sites. Princely art collections were also tied to a specific historical past; aside from the National Museum at New Delhi, which served primarily as a holding place for art organized in a historical didactic program, there was little interest in developing a national museum culture for the study and exhibition of artifacts as ‘art.’[19] Instead, regional site museums based around important archaeological and historical sites were the most common way of organizing ‘museums.’

The twenty-four geographic divisions of the Archeological Survey of India, headquartered in Delhi, were tasked with preservation and archaeological work and with maintaining regional site museums across the country.

Early Indian Private Collections

Samarendranath Gupta (1887-1964), artist and collector.

Many in the world of cultural heritage appear unaware that some of today’s great Western collections of Indian art – as well as foundational collections in Indian museums – are based on the magnificent collections originally formed by scholarly Indian collectors. While some colonial period British and other foreign collectors brought great Indian objects back to the West, the most important collectors were Indians themselves. Indeed, the earliest major collections that formed the National Museum Collection in New Delhi came from private holdings, including those of B.N. Treasurywala, Eric Dickinson, Srinavasan Gopalachari, and Samarendra Nath Gupta.[20] At the time of independence, ASI Director Sir Mortimer Wheeler urged such acquisitions, saying, “One can’t build a National Gallery with a few broken stones and inscriptions. We must have colourful exhibits of pictures and paintings!”[21]

This is not the place to describe how the eclectic dealer Radha Krishna Bharany enabled the building of many early collections, both Indian and Western, or the enormous interest in collecting Indian art that began in the U.S. under the influence of the great scholar Ananda Coomaraswamy when he and his collection came to the Boston Museum of Fine Art. But it must be said that a major factor in the dispersal of great early collections made by Indian collectors was the reluctance of Indian officials to acquire important collections for the nation.

East India palace display, late 19th C. collection.

As the Indian collectors of the 19th and early 20th centuries died, their families needed to sell their collections, and even though many wished to keep them in situ, their collections left the country because Indian museums could not or would not buy them.[22] At the same time, the government actively discouraged private ownership through punitive tax measures and usurpation of private property rights. The 1972 Antiquities and Art Treasures Act made it illegal to export any ‘antiquitiy’ over 100 years old and documents over 75 years old. It required registration of all antiquities and a license to sell or transfer them even within India. Under its Section 19(2), the Act also allowed the Central Government to order their compulsory acquisition at a price determined by the government.

These are just some of the reasons that Dr. Pratapaditya Pal has described the passage of the 1972 Antiquities Act by the Government of India as “the single act of folly [that] has probably done more to encourage the flight of Indian art abroad and to discourage collecting in India than the so-called dishonesty and greed of dealers and collectors.”[23]

How Did ASI Fail to Manage India’s Heritage?

In its first century, both British and Indian scholars at ASI made enormous contributions to the world’s understanding of the history of the subcontinent. Indian archaeologists continued to make major discoveries during the 20th century that have dramatically altered how the world understands the development of civilization and society in the subcontinent. Indian scholarship has bettered our understanding of ancient epigraphy, numismatics, climatology, and many other fields of research. The contributions of M.G. Majumdar, R.D. Banerji, D.K. Chakrabarti, K.N. Dikshit, H.D. Sankalia, S.P. Gupta, K. Devi, A. Gosh, and many others have brought deserved fame and international respect to the fields of Indian prehistory and history. Distinguished Indian archaeologists and scholars at ASI continue to add to our historical understanding.

Aerial view of the Citadel Mound at Mohenjo-daro prior to Wheeler’s 1950 excavations.

But the ASI has never been sufficiently funded and staffed. Even before independence in 1947, the agency was expected not only to perform its original tasks of archaeological excavation and research, but also to physically manage, conserve, protect and maintain over three thousand of India’s estimated 80,000-500,000 monuments. The ASI was also tasked with supervising numerous local museums at archaeological sites and major monuments.

Regrettably, ASI’s administrative structure failed to advance along with Indian scholarship. Despite the passage of new laws and regulations, neither the ASI nor the National Archives of India has been modernized since independence. Policies suited to the responsibilities of the ASI as they were one hundred and fifty years ago are still present. In particular, the agency has been unable to meet the challenges posed by urban development and rural stagnation. The work was already overwhelming decades ago, and appears almost impossible today, after many years of underfunding, site encroachment, bureaucratic indifference, and the pressures of increasing population and industrial development.

Does India Meet the Legal Requirements of the CPIA?

“The MoU will be signed very soon between the Ministry of Culture and its American counterpart…And, we have worked out all the modalities.”[24] Union Culture Secretary Govid Mohan at the August 2023 G20 meeting in Varanasi, India.

“… the US Embassy in New Delhi told The Indian Express, ‘We are eager to conclude a bilateral CPA, which would help to prevent illegal trafficking of cultural property from India to the US … When objects are seized and forfeited under import restrictions created by the CPAs, there is a simplified process for returning objects to the partner country. The partner country does not have to prove the item is theirs. Rather, the United States automatically offers it to them for return,’ the US Embassy spokesperson said.” The Indian Express, November 27, 2023.[25]

India’s government has been clear that its intent in signing an MOU is not to stop looting. India is seeking an MOU in order to – in its own words – make it easier to claim and repatriate objects taken decades or even hundreds of years ago. Indeed, a number of the objects India is seeking to retrieve from the West were taken during the conquest of India by Portuguese, French, and then British colonial rulers, the Koh-i-Noor diamond presented to Queen Victoria in 1850 being a primary example.[26]

Victoria, Queen of Great Britain, Empress of India, Jubilee, 1887, cabinet photo.

Under these circumstances, there remain serious concerns, especially for the U.S. museum community, that an MOU would be used to justify claims for repatriation of objects that left India with official or unofficial blessing decades ago – something an MOU legally cannot do.[27]

By law, the CPIA only restricts imports of objects that left source countries less than ten years before. Yet U.S. Customs has long made it a practice to challenge importers to produce evidence of past export far beyond the requirements of the law. If Customs actually followed the affidavit procedure set forth in the CPIA instead of demanding impossible proofs of permitted export from thirty to fifty years ago, an MOU with India would have little measurable impact. There is already more than sufficient Indian art already in circulation outside of India to satisfy any conceivable future market. Unfortunately, the barriers of overzealous Customs enforcement and retroactive requirements for documentation – combined with India’s interpretation of an MOU as a license for unwarranted demands for repatriation – could be devastating for long-held collections in U.S. museums.

Determination 1: Is there a Current Situation of Looting Imperiling India’s Cultural Heritage?

There is a several thousand-year history of international trade in Indian luxury products of all kinds, including virtually everything on India’s list of requested import restrictions. Indian art and artifacts have been openly sold and exported – as art – throughout the modern age, during most of which time there were no real restrictions on movable cultural property. As a result, there are innumerable Indian objects in circulation worldwide. Only in the last seventy years has there been any attempt to limit that trade to newly made goods – and only in the last two decades has there been a serious attempt at enforcement.

Jeweled flask given to Clive of India after the Battle of Plassey in 1757.

The problems faced by India’s cultural administration today are many, but looting for sale barely registers among them. Analyses by Indian auditors prepared for its Parliament, the Lok Sabah, show that loss of heritage results primarily from past and present neglect of the vast majority of sites, decades of ignoring laws prohibiting encroaching development, indifference to what might be called ‘ordinary’ daily corruption and a massive, overweighted administrative apparatus that excels at passing the buck.[28]

Under colonial administration, India did not rigorously enforce its own export laws – enabling low level officials in the 19th century to accept a fee in lieu of papers or allowing exceptions or ways to work around them in the 20th – regardless of the commodity being exported. The vast numbers of Indian artworks made available in Europe and the UK through this system enabled American philanthropists and collectors to acquire thousands of works that were later donated to U.S. museums. Soon after independence, India welcomed academic specialists working to build collections for U.S. museums. In mid-century, Jawaharlal Nehru himself facilitated the export of Indian and Nepalese art collected by Stella Kramrisch,[29] much of which is now at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.[30]

For most of the seventy years since independence, Indian art dealers have acted with impunity to export many of the same objects and artifacts that India now seeks to restrict. Decorative arts sellers all over the world have openly exported shipping containers full of antique objects, from architectural wood, marble, sandstone jalis, and old furniture. Book and manuscript dealers have done the same, as have traders in antique textiles. There are hundreds of antique dealers around the world who sell such ordinary Indian antiques.

Narada Visits Valmiki, painting, made for a manuscript of the Ramayana epic, Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Maryland, USA, Gift of John and Berthe Ford, 2002. Creative Commons license.

Undoubtedly, there are still a few criminal looters stealing from temples in India, given the hundreds of thousands of temples and shrines scattered across the nation. Even this is on the decline, however, as the law enforcement ethos in India has changed in response to the ruling party’s current interpretation of ‘protecting cultural heritage’ as synonymous with promoting Hinduism. With growing awareness, the incidence of crime has greatly diminished.

Furthermore, Western museums, collectors, and art dealers are no longer willing to purchase ancient objects – particularly archaeological materials or objects from temples such as stone sculptures or bronzes – unless the objects left India long ago and have a record of ownership in the West. Is there a market for recently looted goods outside of India? Not in the United States or Europe.

Nor is everything returned to India is as it is reported. On June 7, 2016, U.S. Attorney General Loretta Lynch presented more than 200 Indian art ‘treasures,’ said to be worth many millions of dollars, to Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi at a Washington DC ceremony. Many of the ‘treasures’ were seized and deaccessioned objects resulting from a nearly decade-long investigation, Operation Hidden Idol, into the activities of Indian art dealer Subhash Kapoor. Photographs of the returns ceremony did include one very valuable statue, a Manikkavichavakar worth about U.S. $1,000,000. According to officials, the Manikkavichavakar was voluntarily returned from a U.S. private collection. Other returned objects that belonged to Subhash Kapoor were far less valuable than claimed or simply not authentic. As one Indian official later told a journalist, “We brought back what was genuine, and left the rest there.”[31]

Powder Flask, 18th – 1st half 19th C. (late Mughal), hippopotamus ivory, Acquired by Henry Walters in 1925; Walters Art Museum, 1931.

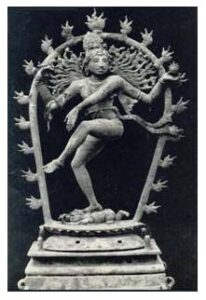

Other nations have also returned objects to India in recent years. Two Chola bronzes purchased by the National Gallery of Australia from Subash Kapoor were personally delivered by Australian Prime Minister Abbott to Indian Prime Minister Modi in September 2014. However, the statues from Australia, a Sripuranthan Nataraja and the Vriddhachalam Ardhnari, were not returned as a result of Indian government initiatives, but by lobbying by a team of repatriation enthusiasts called the India Pride Project.[32]

The Archeological Survey of India has not initiated repatriation cases so far. However, an ‘Idol Wing’ unit of the economic section of the Tamil Nadu police was established specifically to deal with thefts from temples. The Idol Wing unit remained inactive from 1986 – 2006, when it was revived in response to new international interest.[33] Tamil Nadu village temples hold many thousands of bronze and stone statues, many from the 11th-14th century. When these go missing, the Idol Wing unit is authorized to register cases independently for any missing “idols” valued at over 500,000 rupees (about $8,000) and over 100 years old.

The Sivapuram Nataraja

Sivapuram-Nataraja, bronze, Norton Simon Foundation.

The most notable thefts of Indian heritage are long in the past and their history is often more ambiguous than is reported. The Indian government made its first repatriation claim against a foreign held object, a very large and beautiful bronze sculpture of Siva as Lord of the Dance, known as the Sivapuram Nataraja, in the 1970s. The sculpture was found in 1951, together with five other bronzes, in a farmer’s field in Tamil Nadu state, in southern India. Although considered government property under India’s Treasure Act, the statue was placed in custody of the nearby Sivagurunathaswamy temple.[34] Five years later, under pretense of needed conservation, several individuals sent the statues to a nearby restorer, who made copies that were returned to the temple while the originals were sold.

The authentic Sivapuram Nataraja eventually passed into the well-known private collection of Boman Behram in Bangalore.[35]–[36] In 1969, the statue went to a New York art dealer who sold it to California businessman and philanthropist Norton Simon in 1972 for his eponymous museum in Pasadena, California.

Meanwhile, a British Museum curator had inspected the sculptures in the Sivagurunathaswamy temple and identified them as fakes. Soon after, the Indian government claimed the Norton Simon Museum sculpture and asked for its restitution.[37] As the statue was in the UK for restoration, India succeeded in getting Scotland Yard to impound the statue there. In addition to claiming that the statue was exported unlawfully, India also raised an unprecedented argument that the statue was not “property” but had divine, godlike properties that made it a legal entity able to sue on its own behalf to be returned to India.

The Norton Simon Foundation countered that the statue had been legally imported into the U.S. and that the Indian government had abandoned its interest, having known the statue’s whereabouts for decades and taken no steps to recover it while it was displayed as part of the famous Boman Behram collection. The case was eventually resolved through negotiation. The Norton Simon Foundation agreed to recognize India’s ownership and return the statue to India. India agreed to allow the statue to be displayed in the newly opened Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, California for ten years, and gave the foundation carte blanche to purchase any Indian antiquity already outside of India with complete immunity from suit for a period of one year.

Acquittal of Vaman Narayan Ghiya, Parrot Lady Seizure, and Case of Subash Kapoor

Seized idols on the Idol Wing website, Chennai, Tamil Nadu. India.

Widespread foreign publicity about the wholesale export of important antiquities to Europe and the UK by notorious ‘idol thief’Vaman Narayan Ghiya in the 1990s helped prompt the first major Indian police investigation of a smuggling case involving antiquities.[38] The Ghiya case also spurred increased support for the moribund Idol Wing police unit in Tamil Nadu State. Ghiya may have been the most prolific smuggler of Indian antiquities of all time. He had been the most prominent dealer in India, trading in antique sculptures for more than thirty years in Rajasthan.[39] During the 1980s, he is said to have employed multiple gangs of local thieves to take antique sculptures from temples, then shipped them to auction houses and clients in Europe and the UK.[40]

Ghiya’s extensive antiquities trading network received international attention in 1997, when British journalist Peter Watson published a book[41] alleging that Ghiya had flooded Sotheby’s auction house with dozens of highly important ancient stone and bronze gods and goddesses from neglected Indian temple sites in the early 1980s.

According to the Jaipur police[42], India’s Central Bureau of Investigation had long suspected that Ghiya was smuggling art. In 2002, using information from Watson’s book, they began a year-long investigation of Ghiya and finally searched Ghiya’s home in a dawn raid on June 7, 2003.There they discovered hundreds of photographs of stone figures of Indian Hindu deities, Jain Tirthankaras, and Chola bronzes. They also found sixty-eight catalogs from Sotheby’s and Christies.[43] After Ghiya’s arrest, police searched his farm and a half dozen urban storage spaces and warehouses and found about nine hundred objects.

Hawa Mahal or Palace of Winds, Jaipur, India, photo by Diego Delso, 4 December 2009, license CC BY-SA

A trial followed but Ghiya was convicted[44] only of dishonestly receiving stolen property[45] and habitually dealing in stolen property,[46] relatively minor offences under the Antiquities and Art Treasures Act. He was acquitted of violations of laws against theft,[47] criminal conspiracy,[48] some of the charged instances of habitually dealing in stolen property, and of assisting in concealment of stolen property,[49] belonging to a gang of thieves[50] and selling antiquities without a license.[51]

The court’s failure to convict on most of the charges took many by surprise, but the final outcome was even stranger. In 2014, two separate appeals courts effectively cleared Ghiya of all charges, even condemning the police for misbehavior. A high court for Rajasthan at Jaipur Bench, Jaipur denied the government’s request for the acquittals to be reversed.[52] In a separate judgement issued the same day, the High Court of Judicature for Rajasthan overturned Ghiya’s remaining earlier convictions for dishonestly receiving and dealing in stolen property.[53] Moreover, the Court strongly criticized the police for “not maintaining mandatory standards of safe custody of evidence.”[54]

The High Court announced that a Ghiya Collection of South Asian Art made up of the objects seized in India would be stored and eventually displayed at Jaipur’s Palace of Winds. According to Indian officials, the Palace of Winds lacks security measures sufficient for the exhibition of valuable artifacts, and some nine hundred objects were said to be in safe storage. However, a 2017 expose in the Hindustan Times revealed that 700 objects were actually stored in a police shed and in the open air in the backyard of the Vidyadhar Nagar Police Station at Jaipur.[55] The key to the storage shed was reported lost. The Indian government has not made claims for objects sold earlier by Ghiya in Europe.

Prime Minister Shri Narendra Modi at the presentation of the Parrot Lady statue with the Prime Minister of Canada, Mr. Stephen Harper, in Ottawa, Canada on April 15, 2015. Government Open Data License – India (GODL).

In the case of the ‘Parrot Lady’ in 2011, a stone statue was seized in Canada after import from the U.S. The importer was a retiree in Alberta who bought the statue on eBay for $3,818.59 as a replica to decorate her home.[56] As a matter of routine, the Department of Canadian Heritage timely notified the Indian High Commission (IHC) in Ottawa of the 2011 seizure, and sought information regarding whether the sculpture was authentic. Three years later, the IHC responded that the statue was from a twelfth century Khajuraho temple site in central India, a World Monument site. Canada’s Cultural Property Export and Import Act[57] (CPEIA), makes import of cultural property illegally exported from a State that is also signatory to the 1970 UNESCO Convention illegal under Canadian law.[58]

Although India had been unaware that the statue was missing before the seizure and was unable to supply either its former location or proof of illegal export within three years as required by the Canadian law,[59] Canadian officials eventually decided that the statue should be deemed to be from a Khajuraho temple. Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper presented the statue to then Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India during the latter’s state visit to Ottawa in April 2015.[60]

Most recently, India has received returns of numerous stone and stucco sculptures recovered in the case against Subhash Chandra Kapoor, including several important sculptures returned by the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) to India.[61] The case against Kapoor has been ongoing for over a decade in both India and the United States and made Subash Kapoor a ‘poster boy’ for antiquities malfeasance in the press. In 1974, Kapoor, the son of an Indian antique dealer, immigrated to the U.S. and opened a gallery in New York, Art of the Past, selling manuscripts, miniatures and other Indian antiques. In 2011, Kapoor was accused of smuggling ancient sculptures taken from temple sites in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu, allegedly filling the role left after the arrest of Naman Ghiya. Several temple robbers arrested in the Tamil Nadu region implicated Kapoor as the eventual recipient of their stolen goods via a chain of local dealers.

Subash Kapoor, imprisoned in Tamil Nadu, India, 08-19-2022, India TV.

Information shared by a former partner of Kapoor prompted a U.S. investigation into the Art of the Past gallery in 2011. That same year, Tamil Nadu police issued a warrant for Kapoor’s arrest and India’s Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) issued a Red Corner Notice through Interpol. When Kapoor traveled from the U.S. he was detained and eventually extradited to India, and imprisoned in Tamil Nadu State. Kapoor’s sister, Sareen Kapoor, was arrested by New York County officers; four bronze Chola statues seized from her were valued at a total of $14.5 million dollars. All four statues had been identified as stolen in 2008 by the Tamil Nadu police.

Soon after, Homeland Security Investigations raided a Manhattan storage facility used by Kapoor, seizing 2,622 miscellaneous artifacts. Hundreds of these artifacts were returned to the Government of India by U.S. officials, some real, and some effectively ‘garden statuary,’ just as they had been declared to U.S. Customs.[62]

The charges against Kapoor prompted subsequent voluntary returns; a number of private collectors and nine U.S. and several international museums returned objects either sold or donated to them by Kapoor to India. In September 2014, two important statues sold by Kapoor to the National Gallery of Australia were handed over by Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott during an official visit to New Delhi, and in 2015, a statue of the goddess Durga from the Linden Museum was delivered to the Indian Embassy in Germany.

Object returned by Manhattan District attorney identified as a Bikshana warrior, Manhattan DA Office, NY.

In India, the case against Subash Kapoor has proceeded very slowly. Although it began in 2012, the first hearing was not held until 2016. On July 7, 2019, a 285-page criminal complaint filed in New York charged Kapoor with grand larceny, conspiracy, and criminal possession of stolen property.[63] Kapoor was sentenced to ten years in prison in Tamil Nadu State in 2022, all of which was accounted as time served. It is expected that he will be extradited from India for trial in the U.S. and the details of his role in the smuggling of Indian cultural property to the U.S. will come to light.

Independent researchers, not the Indian government, have tracked down other items stolen from temples at various times in the last century, primarily using old photographs, many from the French Institute of Pondicherry. However, these records are themselves stored in poor conditions are disappearing despite current efforts to digitally preserve and archive them.

Photographs of temple statues in situ have enabled seizure and return of objects under the National Stolen Property Act in the U.S. These cases would also be deemed stolen and returned under the CPIA without an MOU. In all the cases made public, identification of statues in situ has been sufficient for museums and private collectors to volunteer their return prior to cases being filed. In none of the high-profile cases described above would the existence of an MOU have made any difference.

Determination 2: Has India taken measures consistent with the UNESCO Convention to Protect its Cultural Patrimony?

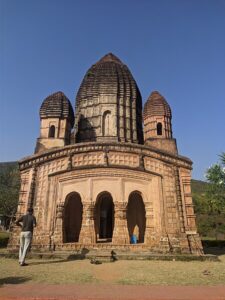

Ruined Pancharatna Temple at Garh Panchakot, Purulia district, West Bengal, India, 5 October 2014, photo Bodhisattwa. CCA-SA 4.0 Int’l.

(1) Overview

In India, cultural heritage has held great political importance only in the 21st century. Still, Indian government commitment to research and conservation of Indian heritage remains lacking. Despite cultural property’s new high visibility and importance as a political issue, there has not been a commensurate increase in funding or improved administration, according to Indian parliamentary resources.

The Antiquities and Art Treasures Act 1972 (No. 52 of 1972) remains India’s foundational national heritage law today.[64] Its passage reflected international discussions surrounding the 1970 UNESCO Convention and its espousal of identity-building through national ownership laws and state control of cultural property.Like other formerly colonized areas, India has embraced a policy of exclusive government control of all art and artifacts. “Cultural property” was very broadly defined to encompass virtually all man-made objects of historical or aesthetic interest. These included all examples of fine arts, books and manuscripts, ethnographic art and objects of historical and scientific interest over seventy-five years old, in addition to movable antiquities, antique artworks, and monuments.

Restoration at Garh Panchakot, 14 March 2022, photo by Milandeep Sarkar. CCA-SA 4.0 Int’l.

Today, India’s vast cultural wealth and its hundreds of thousands of ancient and historic sites are managed under multiple, many-layered bureaucratic systems that are unwieldy and ineffective even according to Indian standards. The Ministry of Culture is the government entity tasked with the development of cultural policy and has oversight of the preservation of cultural heritage under the ASI, the promotion of contemporary and historical Indian culture both domestically and abroad, the management of national museums and their collections, and domestic policies on cultural education. In addition to the federal Union Ministry of Culture and the ASI, there are cultural administrations in every Indian state, and twenty-five state archaeological departments, which have responsibility for monuments that are not under ASI purview. The audits and reports prepared for India’s Parliament that are a major source for this commentary are extremely critical of virtually every aspect of India’s heritage management.

(2) Report on a Failed Heritage System: the CAG Performance Audit of ASI

The Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India on Performance Audit of Preservation and Conservation of Monuments and Antiquities (Report No 18 of 2013),[65] (hereafter “2013 CAG Performance Audit of ASI” or the “2013 Audit”) was a major study analyzing the ASI’s capacities and performance. It is a primary resource for this paper, as is the Follow-up on the Performance Audit of Preservation and Conservation of Monuments and Antiquities, Report No. 10 of 2022,[66] (hereafter “2022 Follow-up Performance Audit” or “2022 Audit”) which assessed the ASI’s performance subsequent to the highly critical 2013 Audit.

Bodhisattva Padmapani, Cave 1, Ajanta Caves, 5th century. From Le Musée absolu, Phaidon, 10-2012, public domain.

The 2013 CAG Performance Audit of ASI was the first thorough analysis of the ASI since independence in 1947. This three-hundred-page survey identified serious problems in the ASI’s physical management of monuments and artifacts, documentation of sites and objects under its protection, management of archaeological projects, operation of site museums, recordkeeping, and coordination with the Ministry of Culture, and law enforcement. A 2022 official review of reforms demanded by Parliament after this devastating appraisal found that there had been no significant improvements.

The ASI was already widely viewed in India as unable to cope with the protection of the more than three thousand monuments it supervises. The audit confirmed the public’s perceptions of the ASI’s failings. It showed that for decades, despite internal awareness of its shortcomings, ASI had been incapable of taking action to improve its performance by initiating new systems of management to replace its moribund bureaucratic structure. The problems found in the audit extended well beyond the ASI itself, pointing to negligence at higher bureaucratic levels at the Ministry of Culture, of which the ASI is a sub-agency. The audit found that the Ministry of Culture did little to supervise or monitor the ASI with respect to its basic responsibilities.[67]

Key issues were the shortage of staff to fulfill the ASI’s workload, and a serious lack of funding available to manage the monuments and objects comprising India’s cultural heritage.

Ghantai Temple, one of the temple ruins at Khajuraho. 21 October 2012, Photo Patty Ho. CCA 2.0 Generic license.

In the summary prefacing the published report, the 2013 CAG Performance Audit of ASI noted among documentation concerns that:

- There has been no comprehensive survey to identify monuments of national importance and include them in the list of centrally protected monuments. Notices naming monuments for protection were often decades out of date or had never been issued.

- There is no ASI database listing the correct number of the monuments protected by it.

- During a physical inspection of the monuments, ninety-two monuments out of the 1,655 inspected could not be traced.

- ASI did not have a database of the number of antiquities in its possession or plans for upgrading any records. 95% of objects had never been displayed. The audit team found that 131 antiquities had been stolen from various monuments and sites and that thirty-seven antiquities had been stolen from site museums. ASI efforts to retrieve these artifacts were ineffective.

- Many World Heritage sites were subject to encroachments and unauthorized constructions; there was no system for removing encroachments and District authorities and police were not cooperative. There was no assessment of required preservation or conservation works.

- The ASI has no approved conservation policy. Conservation policies in practice were based on a 1915 document. Monuments were arbitrarily selected for conservation, and nothing was done in many requiring structural conservation. “Inspection Notes” on monuments were not prepared.

- Less than 1% of the ASI budget is spent on a ‘primary’ ASI activity: exploration and excavation of archaeological sites.

- There was not a single full-time guard at 2,500 of the 3,650 protected national monuments. State, local, and temple authorities are supposed to be responsible for security, but the vast majority of the 80,000-500,000 other monuments in India have no security whatsoever.

- The ASI Headquarters in Delhi could not provide the status of 458 excavation proposals sanctioned in the last five years. No data was available regarding the status of pending excavation reports, and numerous cases of excavation proposals were not undertaken or left incomplete.[68]

Qtub Minar, Delhi, India, Detail, photo by Diego Delso, 10 December 2009, license CC by SA.

Nine years after this devastating report, the 2022 Follow-up Performance Audit found no improvement:

- “Against the recommendation of the PAC [Public Accounts Committee of Indian Parliament], notification of rules and conservation activities under National Conservation Policy, notification of Archaeological Excavation Policy, updation of Antiquities and Art Treasure Act, modification in Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act regarding system for recording footfall was not done,” and “there was no uniform procedure for museums under the control of the Ministry/ASI.”[69]

- “[O]ut of 3693 Centrally Protected Monuments, [Heritage By-Laws and site plans] for only 31 monuments have been notified…”[70]

- “ASI had no strategy or road-map (long term/medium term) to fulfill its mandate… [a] Central Advisory Board on Archaeology conceptualised as apex body to advise ASI on matters relating to archaeology was inactive…” and nothing was done to check incidents of encroachment.[71]

- A National Mission on Monuments and Antiquities launched in 2007 to provide a national database of monuments had done only minimal documentation and basic recording of one-quarter of its total goal. “A list of only 915 monuments was prepared by ASI which was still under consideration.”[72]

- There was physical encroachment (building of shops, housing, and roads) of 546 out of 1655 inspected important ASI monuments.[73]

India Tughlakabad Fort, Delhi. The municipal agency encroached the site by draining out the sewage water into the protected area of the monument. 2022 Performance audit photo.

The 2022 Follow-up Performance Audit also found that:

“PAC had recommended that guidelines for determination of national importance of monuments to be finalised at the earliest and after this a comprehensive survey should be conducted to identify the exact number of monuments that can be protected. [Although the Ministry informed Parliament in 2016 that guidelines had been prepared] …It was noted that guidelines was not prepared, no survey/review of monuments was undertaken by ASI. Instances defining absence of criteria for centrally protected monuments as reported earlier were still existing. In this regard, Ministry/ASI informed that taking of survey is an ongoing phenomenon and the view of PAC was not relevant/possible to be implemented.”[74]

(3) Shortcomings in Museum Management

India National Museum Delhi – 2022 performance audit photo.

Although regional museums, including historical collections and archives founded in the colonial period are generally under the direction of boards of local and state officials, national museums managed by the Ministry of Culture include the National Gallery of Modern Art and the National Museum, both at Delhi.[75] The ASI also manages forty-four site museums, located at important historic monuments and archaeological sites around the country, with nine more museums proposed as of 2013.

The policy of establishing smaller museums with collections related to specific ancient and antique sites was inaugurated in 1904 by John Marshall, the first Director of ASI. Director Mortimer Wheeler established a separate Museums Branch of ASI in 1946. While advanced for their time, the ASI’s core museum guidelines have not been updated since 1915, and updated policies for the acquisition of art objects, conservation, storage, transport, and security were still in the drafting stage in 2015.

The 2013 CAG Performance Audit of ASI states:

“We observed significant shortcomings in the functioning of the museums. The museums did not have any benchmarks or standards for acquisition, conservation or documentation of the art objects possessed by them. The mechanism for evaluation of acquired objects to verify their genuineness was absent in all the museums audited by us. … Poor documentation of the acquired artifacts and the failure to introduce the digital technology for documentation coupled with the absence of physical verification made the artifacts vulnerable to loss. The security system at the museums provided a grim picture in the absence of effective surveillance systems at the sites.”[76]

Archaeology Gallery, Indian Museum, Kolkata, photo Biswarup Ganguly, CCA 3.0.

A joint initiative to establish guidelines for and improve the operation of ASI museums was undertaken in 2013 by the Archaeological Survey of India, the J. Paul Getty Trust, the British Museum and the National Culture Fund.[77] It provided basic instructions for museum administration and management of collections.

Despite this assistance, the 2022 Follow-up Performance Audit found that “comprehensive policy guidelines addressing all issues related with management of antiquities viz. acquisition, accession, custody, rotation, etc.at museums under the control of the Ministry and also for site-museums under ASI was not available. Ministry had informed the PAC about following steps being undertaken by it:

- drafting and finalisation of uniform policy for acquisition of art objects;

- constitution of committee to work out uniform security policy; and

- constitution of committee to prepare standard manual of procedures.”

Nonetheless, the PAC was informed by the Ministry that no such policies or plans had actually been made.[78]

The 2022 Follow-up Performance Audit stated that:

“Despite being the custodian of invaluable antiquities and activities spread all over the country, ASI had no vigilance or monitoring cell to function as a deterrence against theft of antiquities from its monuments. Even though the Central Antiquity Collection (CAC), which is the largest collection of antiquities with ASI had not reported any case of loss/damage, the status could not be verified as no physical verification of its artefacts had been conducted after 2006. As of December 2021, ASI had reported theft of 17 antiquities from its monuments during 2015 to 2021 of which only three were recovered.”[79]

Vairochana Buddha (500- AD-700 AD) From the Aurel Stein Collection, National Museum, Delhi, India, Google Art Project.

A similar lack of accounting for objects was found by the Follow-Up Performance Audit at India’s major museums. For example, the National Museum at Delhi had not accessioned any objects at all except through gifts and had had no Purchase/Acquisition Committee since 1997. The museum had no policy or guidelines for handling objects including their physical verification; while digitization was ongoing, the digitized inventory contained relatively few photographs. Only ten percent of coins were verified. Only 1942 out of 5437 objects supposedly in inventory were located and the curator had no information on the whereabouts of the remaining artefacts. Of 2909 Pre-Columbian objects only 1208 were reported. The Anthropology section was missing 509 objects. Thirty-five percent of their manuscripts have still not been physically verified.

The Aurel Stein collection at the National Museum is one of the most important Central Asian collections in the world. Some 700 objects from it were loaned to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London between 1923-1933, and are still there. No effort was ever made to retrieve the collection from the V&A.[80]

Neither Indian government policy nor Indian laws encourage the establishment of private museums outside government management. The U.S. concept of the museum – one operated by independent philanthropists and managed by trustees that include academics, business-people and wealthy art donors – has not been welcomed as a model by India’s government. Important collections of Indian art owned by Indian citizens (sometimes purchased overseas from older colonial collections) remain overseas due to collectors’ concerns over possible seizure, burdensome customs laws, and unresolved tax issues in India.

(4) Failures of Governance at the Ministry of Culture and the ASI

The 2013 CAG Performance Audit of ASI stated that the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Transport, Tourism and Culture, the Comptroller and Auditor General, the Supreme Court and High Courts of India have all “pointed out severe shortcomings in the functioning of the ASI and museums.”[81] The report states that the Ministry of Culture has ignored the criticisms and concerns of administrative and judicial officials outside of the ministry for decades and that, “[n]o major corrective actions or change in approach was noticed to rectify the deficiencies. Even where some action was initiated, it lacked the organizational will to be completed in a time bound manner.”[82]

The CAG Performance Audit of ASI found instructions from the Ministry of Culture to the ASI to be “random and conflicting,” and said that there was no guidance at all on “many crucial aspects of functioning.”[83] Projects were unmonitored, “some lying incomplete for decades.” When corrections were made, they were to a particular project and did not address systemic issues.[84]

(5) Staff shortages and unqualified personnel

Outer wall friezes at Rukmini Devi Temple, Dwarka, ASI monument number

N-GJ-128. 1 October 2013. Photo Madhuranthakan Jagadeesan, CCA-SA 4.0 Int’l.

In 1984, a Parliamentary committee established to review the ASI’s performance, the Ram Niwas Mirdha Committee, recommended that there be significant increases in staff for the ASI to enable supervision by nine thousand attendants at five thousand monuments and to establish a trained ASI security force.[85] Today, most site security is still outsourced to private companies. The Mirdha Committee also proposed that the ASI should not continue as an administrative body but be reorganized as a specialized scientific and technical institution that could contribute expertise to a separate cultural management entity. Although the government agreed in principle, the Ministry of Culture never acted on the recommendations.

Twenty years after the review by the Mirdah Committee, in 2005, a Parliamentary Standing Committee brought up many of the same issues that it had raised. The Standing Committee was concerned that since 2002, the government had filled the post of Director General of the ASI (and other top posts) with generalist bureaucratic administrators. “The Committee is of the view that a person who has no basic qualification or knowledge of archaeology cannot handle the apex responsibility of a Scientific Institution like Archaeological Survey of India.”[86] They noted that the hiring of bureaucrats from other sectors discouraged experienced staff at ASI from continuing to work in an agency where they could not advance their careers.

However, instead of increasing their hiring requirements, the government reduced them in 2015; removing the requirement that a candidate hold a history or archaeology-related PhD and merely requiring several years’ experience in any government bureaucratic post, paving the way for functionaries to take the place of knowledgeable professionals in the fields of art and archaeology.[87]

There appears to be little hope for the development of a cadre of skilled archaeologists and museologists in India today. According to the 2022 Follow-up Performance Audit:

“It was noted that all 45 posts (under different categories) in the Institute of Archaeology, as mentioned in the previous Report were not filled and lapsed due to delay in framing of Recruitment Rules. Further, enrolment for higher studies was not forthcoming at the National Museum Institute. During 2013 and 2015-17, no student was enrolled for its PhD (Doctor of Philosophy) level courses in History, Conservation and Museology. In this regard, NMI stated (December 2021) that due to UGC regulations restricting number of PhD students under a professor, availability of only five teaching faculty for three NMI PhD courses and minimum time of three years for completing the research work, it was not in a position to invite applications for the course every year.”[88]

Likewise, the 2022 Follow-up Performance Audit found that there was an increase in the vacancy rate for staff since the 2013 audit in all but one of India’s five national museums, ranging from the lowest at the National Museum in Delhi of 20.7% vacancy to the 58.9% vacancy rate at the Indian Museum in Kolkata.[89]

(6) Funding Shortages

Thyagaraja temple, Tiruvarur, by Ssriram mt, 5 January 2019, Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Perhaps the greatest challenge facing Indian cultural heritage today is a lack of funding necessary to address systemic problems in cultural heritage management and to enable the administrative reorganization of the ASI.[90] Funding of ASI has been minimal for many years and is not increasing substantially. In 2007-2008, the ASI estimated Rs. 1,770,000,000 (around $35,400,000 in 2008 dollars) as its annual budget.[91] This includes the revenue generated by the ASI through tourism and ticket collection. The one hundred and seventeen ticketed monuments generate about Rs. 600,000,000 (over $12,000,000). However, three quarters of this ticket revenue is redirected to other sectors at the Ministry of Culture rather than staying within the ASI. World Heritage sites generate far more tourism income proportionately than sites without World Heritage designation – one reason India is seeking World Heritage designations for more than 40 additional sites.[92]

According to the 2013 CAG Performance Audit of ASI, the expenditures by ASI from 2007-2012 were 56% Administrative/Establishment, 41% Conservation Projects (including building site amenities), 1% Excavation Projects, and 2% Site Museums.[93] The 2013 audit also stated that the Culture Ministry allocated funds without apparent reference to planning, funds requirement or absorptive capacity, a problem that continued in 2022.[94]

“As a result, the ASI ignored the conservation needs of several valuable monuments due to paucity of funds. For example, in case of 110 Kos Minars[95] the expenditures incurred during the last five years was only Rs. 38.33 lakh [equal to about $45,000 dollars U.S.]. On many other sites/monuments no money was spent despite dire need of conservation.”[96]

According to the 2013 audit, the Circles/Branches of the ASI prepared estimates in only a few cases. As a result, the ASI ignored the conservation needs of several important monuments due to lack of funds.[97]

The 2022 audit emphasized that tourism accounted for 6.8% of India’s GDP and 8.1% of all employment in 2019.[98] The ASI generates most of its revenue through ticketing monuments, filming charges for movies, and payment for cultural events. While ASI included more monuments in a ticketed category and generated more funds today than in 2013, in some cases this led to the exclusion of the general public, who could not afford entry.[99]

(7) New Legislation Needed but Never Passed

English: Ruins near Hampi village, India. July 2008, 21 July 2009, photo by Adam Jones, adamjones.freeservers.com, CCA-SA 3.0 Unported license.

The 2015-2016 Thirty-Ninth Report of the Public Accounts Committee on the Protection and Conservation of Monuments and Antiquities of the Ministry of Culture was harshly critical of the Ministry of Culture’s apparent apathy in the wake of the 2013 CAG Performance Audit of ASI, expressing:[100]

“extreme displeasure over the absence of an appropriate and effective mechanism for acquisition of antiquities in the country so far, as also the delay in bringing about amendments to the Antiquities and Treasures Act 1972, leading to the development of an illegal domestic and export market for such items, some of which are of great heritage value to the nation. The Committee note with serious concern that the Ministry is yet to bring amendments to the Act even after a lapse of nearly two decades, though the process to amend the Act was initiated in 1997. The Committee therefore desire that the Ministry expedite the finalization of the draft Antiquities and Art Treasures Amendment Bill.”[101]

In response to an Indian Public Accounts Committee’s question regarding the measures taken “to prevent valuable antiquities and artifacts from landing in foreign shores,” a Ministry of Culture representative testified in 2016 that:

“One of the reasons for smuggling is that antiquity prices are very depressed in India. One of the reasons for depressed prices is that under the law you have to register and take permission. Every one year, the last 100 years becomes antiquity. So, it is very difficult for people though modern art sells at a very high cost in India. We are re-drafting the [Antiquities and Art Treasures Act of 1972]. One of the objectives is to make trade in antiquities within the country free. Otherwise, even if a person wants to buy and donate to a museum a lot of issues are there.”[102]

15th C Bugga Ramalingeswara temple, Tadipatri, Andhra Pradesh, 4 September 2019, photo Sarah Welch, CCO 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

According to the 2013 CAG Performance Audit of ASI, the ASI has been aware of the need to completely overhaul and update India’s current law on cultural property, the Antiquities and Art Treasures Act of 1972 (hereafter “AAT Act”), since 1987.[103] However, “No note has been taken by the concerned authorities” of this need.[104] Recent attempts to pass new laws to reorganize the administration of cultural property in India have gone nowhere. The National Commission for Heritage Sites Bill of 2009 would have established a National Heritage Sites Commission as a step towards protecting sites and monuments lying in a state of neglect.[105] The legislation referred directly to India’s signing in 1977 of the 1972 UNESCO Convention; it called for “appropriate legal, scientific, technical, administrative and financial measures necessary for the identification, protection, conservation, presentation and rehabilitation of cultural and natural heritages.” Seven years later, in 2016, the Ministry of Culture formally announced the abandonment of the project. After several other false starts, no other legislation has been passed. Government authorities have for the most part looked the other way instead of enforcing the laws on the books or providing necessary enforcement support in the decades since independence.[106]

(8) Why don’t Indians collect Indian Art?

For decades, wealthy Indians who acquired art overseas generally kept it overseas – and most still do. Heavy customs duties and burdensome official requirements for documentation and registration for private collections inside India have encouraged major Indian collectors to hold their artworks in Europe, the U.S. and other foreign countries. Even after passage of a 2009 regulation[107] ending duties on imports of “books and antiquities” over one hundred years old, vague laws, erratic enforcement, and the threat that unregistered antiquities might be seized continue to deter Indian citizens from collecting Indian art and from developing a philanthropic culture that would support world-class museums inside India for its public benefit.[108]

An old ticket of the Heritage Monuments of India issued by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), from a personal collection, Photo by Billjones94, 2 June 2022, CCA-SA 40 International license

An Antiquities and Art Treasures Regulation, Export and Import Control Bill to amend the 1972 Antiquities and Art Treasures Act to make it easier to collect art inside India was finally proposed in 2017.[109] A major goal of the bill was to modernize the domestic sale, import and export of antiques and to make trade procedures more transparent, in part to track cultural objects and in part to help build a broader base of domestic cultural institutions. Instead of issuing licenses to sell antiquities, the bill would require dealers to upload their inventory into a computer database of goods for sale. Unfortunately, Indian collectors and art dealers are wary of inconsistent government treatment and would have to be convinced to participate in the scheme.

Under the draft bill, the importation of antiquities would have required prior uploading of a detailed description of the imported objects to a Web portal and approval of the import. The ASI would assist in processing any imported or exported article. The Indian Government would be enabled to relax import duties under certain unspecified conditions, which might have facilitated the return of major collections of ancient Indian art. The bill also would have granted the ASI the power to raid any residence to seek wrongfully held antiquities. However, the proposed 2017 bill failed to pass, leaving the unwelcoming status quo unchanged.

(9) Non-Governmental Efforts, Adopt a Heritage, and Other Cultural Projects

While public involvement in heritage is always a positive, India’s government has made it nearly impossible to move forward in cultural matters unless proposals promote tourism or have a direct public relations benefit for politicians. A non-governmental organization, INTACH,[110] the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage, was created in 1984 as part of a citizen’s conservation movement frustrated with the ASI’s bureaucracy. INTACH supports public education and heritage documentation projects. In many ways, INTACH supplements and supersedes the work of the ASI. It is said to have recorded over seventy thousand monuments, of which sixty thousand are not under any governmental supervision. INTACH is also concerned with preserving India’s living artistic heritage and has listed fifty-four thousand contemporary heritage resources in one hundred and fifty cities and towns across India.[111] Funding for a broad range of cultural projects also comes through the National Culture Fund,[112] (NCF) established in 1996 by the Ministry of Culture. The National Culture Fund solicits contributions from State Governments, the private sector and individuals.[113]

Puma advertisement video in which graffiti was sprayed on a Delhi, India monument.

Unwilling to pay for basic maintenance at heritage sites on its own, the Indian government recently launched a scheme inviting private companies and other entities to assist in the development of tourist facilities at major Indian monuments. This ‘Adopt-A-Heritage’ scheme, inspired by similar efforts in Italy, was announced in 2017 by the Ministry of Tourism in collaboration with ASI to allow corporate control of certain monuments and heritage sites, so that their maintenance and operations could be handled more professionally.[114] The program’s aims are to “entrust heritage sites/monuments and other tourist sites to private sector companies, public sector companies and individuals for the development of tourist amenities.” The Parliamentary Standing Committee on Transport, Tourism and Culture announced on March 6, 2018 that: “The committee recommends that under the corporate social responsibility, major corporate (houses) may be compelled to adopt heritage sites.”[115] The Initial plan was to delegate management of ninety-three ticketed ASI monuments to corporate entities. Five years later, bylaws for these monuments are still being framed by the Ministry, according to the 2022 Follow-up Performance Audit.[116]

An Adopt-A-Heritage contract to manage and develop tourism for a five year period at one of India’s most popular tourist attractions, Delhi’s Red Fort, was signed with Dalmia Bharat,[117] a major cement and sugar company, on April 9, 2018.[118] Under the contract, Dalmia Bharat will develop the Red Fort by providing drinking water kiosks, benches, signage, and maps, upgrading toilets, lighting the pathways and bollards, performing restoration work and landscaping, building a 1,000-square-foot visitor facility center, creating 3-D projection mapping of the Red Fort’s interior and exterior, installing battery-operated vehicles, and operating a cafeteria with a Red Fort theme.[119] Unfortunately, such projects are solely focused on tourism and exploitation rather than the preservation of Indian heritage.

Determination 3. Will an MOU be of Substantial Benefit in Deterring Looting?

The Indian scholar Dr. Pratapaditya Pal stated when interviewed for this commentary that “since almost 1995 the import of Indian art of all sorts and periods that arrived from the geographical area of the Indian subcontinent that constitutes today’s nation known as India has considerably decreased.”[120]

Kapoor inventory group with some distinctive fakes, screenshot from Homeland Security Investigations video.

The removal of the primary looting organizations in India has been one contributing factor to this change, but the highly effective self-policing undertaken by museums, auction houses, galleries and collectors in the U.S., Europe, and the U.K today does much more. ‘Freshly looted’ objects – any objects without a lengthy provenance – are simply not acceptable in today’s art market or in museums. Since Subash Kapoor’s arrest over a decade ago, recently looted objects have not been reported in the U.S. Instead, objects long in circulation have been identified through decades-old photographic records and documentary research. This research is almost always initiated outside of India’s government, by activists for repatriation, such as the India Pride Project.[121] When proof that objects were stolen is provided to U.S. museums and collectors, they are usually returned voluntarily and no seizure ensues.[122]

It should also be clear that that import restrictions will do nothing to safeguard a heritage that the Indian government has abandoned. The primary threat to India’s heritage is from negligence, unauthorized development, and deliberate destruction, not looting.

Unpermitted development of any kind at historic and ancient monuments had been strictly prohibited in India since long before Independence. The Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act, 1958, amended in 1992 and again in 2010,[123] prohibited any erection of a structure or any electrical or drains construction within one hundred meters of the borders of a listed monument.

Illegal buildings around baoli, threatening its collapse. Photo Varun Shiv Kapur, New Delhi, India, CCA 2.0.