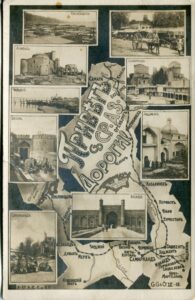

Postcard, “Welcome to Central Asia,” 1930s.

PRECIS

Late last year, as part of an effort to boost U.S.-Uzbekistan government relations and increase cooperation on issues such as security, the U.S. Department of State accepted a request for an agreement to block U.S. access to Uzbekistan’s ancient and ethnographic art from 50,000 BC to 1917. A Cultural Property Advisory Committee hearing took place at the end of January 2023, and was followed closely by a visit to Tashkent by Secretary of State Anthony Blinken on March 1st. A decision on Uzbekistan’s request hasn’t yet been announced, but no CPAC request has been denied in the last twenty years.

Cultural property agreements are useful soft-power tools for the Department of State, but can harm important U.S. cultural interests. Over-broad agreements that serve as virtual embargoes cause harm to collecting museums, to religious and ethnic minorities who are denied access to their own heritage, and to thousands of small businesses. Serious human rights concerns are waved aside in order to facilitate more ‘important’ State Department goals. These can include military matters, terrorism or drugs – or may grease the entry of major U.S. businesses into burgeoning markets.

In consequence, the U.S. has repeatedly signed cultural property agreements with totalitarian and authoritarian regimes that are destroyers of minority cultural heritage and severe abuses of human and religious rights. China, Egypt, and Turkey are some of the worst offenders who have such agreements. A U.S. cultural property agreement with Libya, which has no central government and which utterly fails to protect its archaeological sites and built heritage was renewed in early 2023.

Uzbekistan’s request to block imports comes under a U.S. law designed to be used only when there is a current, serious situation of “looting” of art and artifacts in a foreign nation – and when the U.S. is a primary market for these looted objects.

However, there is no evidence that there is looting in Uzbekistan today except at a very petty, ad hoc level. People may find a pot or utensil sticking out of the ground when plowing a field or a handful of coins hidden from early invaders when they repair an old wall. In more out of the way villages, archaeologists have reported that a few people hunt for coins with metal detectors – an activity that local police are well aware of. However, turning a blind eye does not extend to export. Uzbekistan has rigorous laws, an ample national police force and an active customs authority.

Moreover, Uzbekistan’s request is excessively broad. It covers archaeological material dating from the Paleolithic period (50,000 BCE) to the 18th century CE and ethnological material dating from the 7th century CE to 1917 CE.[1] In other words, the request seeks U.S. import restrictions on virtually everything made by human hands from the beginning of human habitation to the Bolshevik revolution and the end of the First World War. There is no possible rationale for the argument that every single item ever made on Uzbekistan’s territory is being looted and sold in the U.S.

The facts on Uzbekistan versus the requirements of U.S. law

Seated female, Bronze Age, Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex, possibly Turkmenistan, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY.

Under Uzbekistan law, any object over 50 years old cannot be exported without permission from the Cultural Ministry – which is usually not granted – and effectively, therefore, has no market. Rightly or wrongly, independent Uzbekistan has continued a policy established under Soviet communism of State control over private property, including art and ordinary handicrafts.

Uzbekistan’s government is intolerant of any form of unregulated economic activity. There is no professional looting because there is no local market for selling antiquities, and no way for ordinary Uzbeks to access international markets. Only the Uzbek elite – in other words its officials –if they wish to do so, can participate in in illicit activities involving art. When officials have done so, it appears that they act with impunity.

A U.S. law, the Convention on Cultural Property Implementation Act (CPIA), limits the President’s executive authority to impose import restrictions on archaeological and ethnological objects. The Cultural Property Advisory Committee (CPAC) at the State Department’s Cultural Heritage Bureau, was created to provide the executive with useful, expert advice about this process.

Import restrictions may only be applied to archaeological and ethnological artifacts of “cultural significance” “first discovered within” and “subject to the export control” of a specific UNESCO State Party.[2] They must be part of a “concerted international response” of other market nations, and can only be applied after less onerous “self-help” measures are tried.[3] They must also be consistent with the general interest of the international community in the interchange of cultural property among nations for scientific, cultural, and educational purposes.[4]

Central Asian Bronze Age vessels and stone plinths, Turkmenistan, photo Victor Sarianidi.

Congress knew a number of UNESCO State Parties were run by authoritarian governments that declared everything “old” State Property. For that reason, Congress structured the CPIA to ensure that the United States maintained its “independent judgment” on whether and the U.S. would enforce foreign export controls.[5]

The truth about how objects left Uzbekistan – and the effect of a U.S.-Uzbekistan import ban

The majority of objects for which restrictions are being sought left Uzbekistan’s territory at key periods over the last 150 years, an exodus driven by Russian colonial and Soviet policies. Objects were sent to Russian museums under Russian colonization, seized from the homes of ordinary private citizens under the Bolsheviks, and carried away by refugees as personal belongings in waves of emigration in which people fled Russian occupation, then Communism, forced collectivization and starvation.

Wallpainting, Sogdian, Afrasiab.

The best of what remained was gathered together in public museums and archives after the creation of the Uzbek Soviet republic, the UzSSR, Some of this was drained away in the early years of Uzbekistan’s independence, stolen by the former UzSSR elite and the family and cronies of former President Islam Karimov. What remains in Uzbekistan are objects documented in sites and monuments and museum collections, no longer at risk of looting.

Uzbekistan’s pre-Islamic material culture is not in the form of royal monuments such as Persepolis. Objects continue to be found in archaeological sites, excavated by Uzbek archaeologists, and certainly more will be discovered in the future. No doubt, like the site of Termez, on Afghanistan’s border, these sites will be properly excavated under government supervision and beautiful site museums created for public appreciation.

Islamic period Central Asia saw the construction of some of the greatest buildings ever built, and these too remain. Uzbekistan’s massive 14th-16th century mosques and tombs are its greatest tourist attraction. But these are austere buildings – tombs, mosques, and medreses (schools for Islamic thought), decorated with ornate tile and brickwork.

The best of Uzbekistan’s material culture, outside of its museums and libraries, was taken away long ago. As shown by its 2019 plan to publish 40 volumes of Uzbekistan art in Russian and other foreign collections (discussed below), Uzbekistan’s government already acknowledges that during a century and a half of Russian occupation and Soviet domination, much important archaeological material from excavations and in Uzbekistan’s public and religious collections left the territory of present-day Uzbekistan for Russia, with its government’s permission.

Silver and Gilt Plate Showing the Siege of a Castle, Sogdian, 9th–10th century, found in 1909 near village of Anikova, Perm Province , Russia, State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia.

Russia still refuses to repatriate even known looted objects taken by the Soviet army from German museums in WWII, and the Russian government and its museums regard materials taken from Uzbekistan during colonization and the Soviet period as legitimately acquired property. The Government of Uzbekistan, though well aware that many of its most outstanding objects of art and heritage are held today in Russian museums and institutes, is also cognizant of positive aspects of its longstanding relationship and current dependence on Russia’s goodwill and will not seek repatriation from Russia.

Much 19th C material culture, particularly textiles, carpets, made by and privately owned by ordinary people in Uzbekistan, is also in European and U.S. collections. Most of these items were made commercially for trade and export in the first place. The museum-worthy objects of this kind currently circulating in international markets left Uzbekistan long ago. Emigrés who fled Uzbekistan to Afghanistan and Israel also brought out their more personal objects of home and tent decoration, costumes, jewelry, and adornment many decades before the creation of today’s Uzbekistan Republic. However, without proof of long-ago export, such items could be seized on import to the U.S.

Objects left Uzbekistan primarily during periods of extreme hardship, through:

- Seizure of valuable property that was taken to Russia during Czarist occupation of Central Asia in the late 19th and early 20th, including not only luxury items but also libraries and archives from the Central Asian khanates and emirates of Kokand, Bukhara, Samarkand, Khiva, Khojent and the Ferghana Valley.

- Seizure of nomadic Turkoman property, stripping them of carpets, costumes, and jewelry (for nomads wear their wealth) as well as their herds, leaving them destitute, by conquering Russian colonial forces in the 19th C, and similarly devastating seizures from Uzbeks, Turkomans and others who participated in resistance movements against Bolshevik forces.

- Massive movements of Turkic and Tajik peoples fleeing forced collectivization, attacks on private property and imminent starvation in Central Asia in the early 20th C, primarily moving to northern Afghanistan with all their goods.

- Emigration of Central Asian Jews bringing out their personal goods starting in the 19th C and continuing throughout the 20th, moving to Afghanistan, Israel, Europe and the U.S.

- Most recently, in the early 1990s, almost entirely sent to Turkey via Turkish traders by desperate people who sold personal possessions for a pittance immediately after the collapse of the Soviet Union. At this time, Uzbekistan’s newly independent government seized businesses, made virtually all exports of handmade goods illegal and at the same time deliberately closed off the supply of cash domestically, in a period of 1000% inflation.

A MOUs primary effect would be to burden U.S. museums and private collectors from accessing goods legitimately in circulation for a century or more. It would cause particular hardship for emigrés from Uzbekistan, especially Central Asian Jews, who would not be able to access their own cultural heritage from foreign countries or travel with family heirlooms. It would impose requirements for (nonexistent) documentary proof of export for textiles and other ethnographic items that left the territory of Uzbekistan 70-150 years ago.

The Historical Background in Antiquity

Ambassadors from Chaganian, and Chach to king Varkhuman of Samarkand. 648-651 CE, Afrasiyab Museum, Samarkand, Uzbekistan.

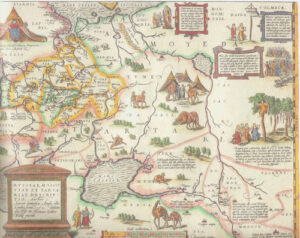

Central Asia is a desert, split by inhospitable mountain chains and dotted with oases, in which city life has been limited to just a few urban centers. Bukhara is 4000 years old, rebuilt so many times that it is mainly built on Old Bukhara. The lands nearby were cultivated as far as the water would stretch. Beyond the edges of cultivation, the steppe primarily supported herding and a nomadic or semi-nomadic lifestyle.

Uzbekistan is a modern construct, a political land division in existence only since 1924. It sits in the approximate center of a much larger natural geographical region extending to the east across present day Xinjiang in China – to the Caucasus in the West – across northern Afghanistan to the south and Kazakhstan to the north. Present day Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan have shared similar histories, religious identities and artistic traditions for thousands of years.

Central Asia was home to one of the world’s earliest and least known civilizations, a Bronze Age culture dating from the late 3rd millennium to around 1500 BCE, located in present day Turkmenistan, Iran, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and including satellite trading sites in southern Pakistan.[6] The Bronze Age produced not only bronze, silver and (occasionally) gold ornaments and seals of great sophistication but also trade goods that traveled 1500 miles by relay to Fertile Crescent, including exceptional beads of lapis, turquoise, carnelian, and other agates that parallel Mesopotamian material.

Sogdian, late 7th–beginning of 8th century CE, Found in 1878, Mal’tsevo, Perm Province, Russia, acquired by the Hermitage in 1925

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia.

The outlying areas of Persia’s Achaemenid Empire (550-330-BCE) reached into Uzbekistan. Figures identified as Central Asians can be seen carrying cloth as tribute in stone friezes at Persepolis. Hellenistic colonists and then Alexander the Great reached Central Asia at its close, blending with oasis cultures and living alongside nomadic peoples whose Animal Style artifacts are found in steppe-lands from the Black Sea to Mongolia. Few objects of either Hellenistic or steppe material culture can be identified as coming from one site or another, and Greek and Roman coins from faraway mints, for a certainty, are found across Central Asia as well as in Britain and Scandinavia.

From the early centuries CE until the advent of Islam, a distinctive, extremely sophisticated Sogdian culture flourished in what is now Uzbekistan. There are remnants of palaces with gorgeous wall paintings and substantial written evidence of extensive trade to China and the Mediterranean by Central Asian entrepreneurs who formed the backbone of the early Silk Road.[7] Russian collections in both Moscow and Petersburg, on the other hand, are very rich in Sogdian materials. Sogdia was a preeminent manufacturer as well as trade center for ancient textiles; Sogdian fabrics have been found in medieval European contexts, but those that have come recently into Near Eastern and Western markets are identified as from northern Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and western China, not Uzbekistan.

These are just a few of the largest cultural influences in a vast region that encompasses much more than present day Uzbekistan, where one can also find remnants of Parthian, Kushan, Sasanian, Hepthalite and other important artistic cultures that were centered outside its borders.

The Islamic period

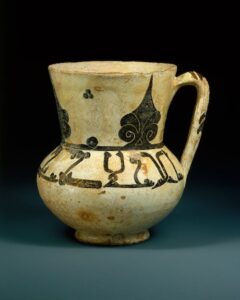

Ewer with Arabic Proverb, “Devotion Fortifies Action”, 10th C, Probably from Iran or present-day Uzbekistan, Nishapur or Samarqand, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The first arrivals into Sogdia at the rise of Islam were Arabs – who burned Sogdian libraries in the 8th C. The first highly cultured Muslim dynasty of Central Asian natives were the 9th-10th C Samanids. They were followed by Seljuks and Mongols. Each controlled enormous areas of Western Asia and the steppe. Central Asian rulers of Turco-Mongol heritage expanded these borders even further, establishing empires of their own, the Ilkhanid, Chagatay and others.

What made this region attractive to conquerors was its location at the center point of the primary international trade route between East and West and the skills of its famous craftsmen, who supplied trade goods for the Silk Road. Samarkand has been famous for its silks since the early centuries CE. When the late 12th century conqueror Chenghiz Khan ordered a city destroyed and its inhabitants slaughtered, he would sometimes spare its artisans, sending them back to Mongolia, where they could be useful.

The Turkic Timur Leng (Tamerlane) assumed the mantle of Chengisid leadership. His descendants were succeeded by the Shaibanids (generally ethnically Uzbek) who swept down from the steppe to push Timur’s descendant Babur into Afghanistan, where, from Kabul, Babur later conquered northern India and founded the Moghul Empire. In Central Asia, the Shaibanids split into successive ruling families in different oasis towns in present day Uzbekistan – Kungrats in Khiva, Mangits in Bukhara, the Keneges of Kokand, Tashkent, and Ferghana.

Standing figure with feathered headdress 12-13th C CE, possibly Iran, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY.

As early as the 10th and 11th centuries CE, great thinkers such as the polymaths al-Biruni, al-Khworezmi (who gave his name to the algorithm), and Ibn Sina (Avicenna) helped to make Central Asian cities into the greatest scientific centers of the Islamic world – bringing astronomy, mathematics, medicine, and other sciences to heights unimagined in the West. At the same time Samarkand, Bukhara, Merv (in present Turkmenistan) and Balkh (in present Afghanistan) were centers of learning, they also sat at the heart of vast trading networks extending through Russia to Scandinavia, through Baghdad to Egypt and beyond.

Even later Uzbek dynasties, though mostly confined to Central Asian homelands, relied heavily on international trade, dealing in everything from textiles to horses to medicinal rhubarb. They continued the entrepreneurial traditions of the Sogdians, acting as middlemen and caravanners for goods along the ancient roads. The most important commodity in the medieval world was textiles, whose value was understood everywhere in the Muslim world.[8]

Manuscripts and books were of the greatest importance in developed Islamic societies. With the arrival of Russian forces in Central Asia in the 19th century, books, manuscripts, and even the entire Khivan state records known as the “Khivan archive” were seized and taken to Russia in 1873.[9] Scholars such as the great Russian Orientalist V.V. Barthold made outstanding historical discoveries through their work with Central Asian manuscripts. Barthold was followed by eminent scholars such as Yuri Bregel, who later moved from Petersburg to the U.S. and taught at Indiana University. Periodically, books from these Russian collections have been returned to Uzbekistan.[10]

Laila and Majnun, Folio from a Khamsa of Nizami, 1431–32 CE, Herat, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

This shuttling of collections to Russia and then sending back what’s not deemed essential has also taken place with textiles and other objects of material culture. Short sections of what were originally 40-foot lengths of luxury silk fabrics are often found in Uzbekistan museums. These full fabric lengths gifted by Khans and Emirs to the Czar in the 19th C were cut in Russia and samples returned to Uzbekistan museums.

Russian museums and institutes also received excavated and architectural early Islamic artifacts and held them for decades, sometimes sending back a selection to Uzbekistan museums. An important scholar of Central Asian history, Paolo Sartori, of the Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften in Vienna, has suggested that some returns were part of a deliberate program to affirm a “fabricated” story of Uzbek statehood, based on the laudatory ceremonies and descriptions that surround such events.[11]

Coins and Other Manufactured Goods

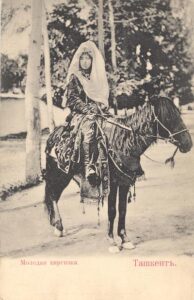

Kirgiz Horsewoman on postcard, Tashkent, late 19th C.

Uzbekistan’s request includes import restrictions on coins and even banknotes. The inclusion of modern coinage, postcards (which were printed in Europe starting in the 19th C), and postage stamps, all of which were machine made, is obviously not in keeping with the definition of “ethnological” material in the CPIA: “(I) the product of a tribal or nonindustrial society, and (II) important to the cultural heritage of a people because of its distinctive characteristics, comparative rarity, or its contribution to the knowledge of the origins, development, or history of that people.”[12]

With the exception of limited local issues, the ancient and antique coins that circulated in the territory of present day Uzbekistan were mostly minted elsewhere. It cannot be assumed that a coin of Bactrian, Kushan, Sassanian or Hephthalite type “circulated primarily” in Uzbekistan – a peripheral ancient location.

The traveler Annette Meakin, an acute observer of Central Asian culture, wrote in 1903 of an active trade in coins by a Kokand agent for Russian curio dealers that involved ancient coins of types clearly not originating in or primarily found in Uzbekistan:

Tetradrachm of Alexander the Great, ca. 325–319 BCE, Iran, Pasargadae, Seleucid.

“Many of these emissaries are of the Hebrew race; and this point is greatly in their favor, for it enables them to gain easy admittance to the houses of native Jews, which in themselves are mines of wealth to the collector of antiquities. I came across one such emissary in Kokand, and was interested in looking over his latest booty, which consisted of several Greek coins, on one of which it was easy to distinguish the head of Alexander the Great, with his name in Greek characters around it; another was a Roman coin of pure gold on which we read the inscription of the Emperor Titus; we also saw several beautifully carved metal caskets… I then asked who would buy them of him. “I sell a good many to private gentlemen,” he replied, “in England and Scotland, who are themselves clever numismatologists and possess priceless collections that have been handed down from father to son for generations. I also sell a great many in America, but the Americans only began to collect fifteen or twenty years ago.”[13]

Under these circumstances, it is not possible to identify with any certainty the country of origin of coins or of a broad range of archaeological artifacts with shared characteristics with those frequently found in other countries, as being “first discovered within” and “subject to the export control” of Uzbekistan, as the U.S. law requires.

The Pre-Modern Era

Russian Colonialism and Central Asia’s Cotton Plantations

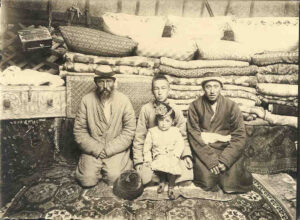

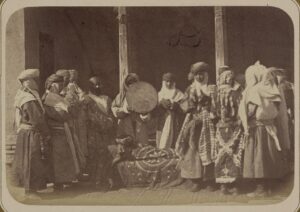

Kirgiz family with Russian child, 3rd quarter 19th C, Kirgiz weavings and urban silk textiles are stacked in yurt. Unknown photographer.

Russia’s 19th C colonization of Central Asia is sometimes portrayed as driven by the Russian textile industry’s need for a secure supply of cotton when Egyptian and American sources were threatened. In fact, the forces and ambitions driving Central Asian conquest were military, not mercantile. Soldiers were eager to fight in Central Asia in order to obtain medals, promotion and loot. Generals seeking Imperial approval often misrepresented the natives as wild religious fanatics in order to bolster their reputations.[14] Strategic concerns, particularly the fear of an invasion by the British via Afghanistan or Iran, was a key reason why Central Asia remained under military rule for the entire period of Russian colonial occupation. In the end, access to cotton was more of a rationale than a reason.

The real cost of Central Asian cotton monoculture became clear in the years after the 1917 Russian revolution. In the chaos following the revolution, Central Asia was cut off from essential food deliveries. With most farmland used for cotton, Central Asia was no longer able to feed itself. Between 1919 and 1923, an estimated one million people died of starvation. This disaster, compounded by forced collectivization, also resulted in the loss of some two-thirds of Central Asia’s sheep, goats, and cattle-herds. As a result, large numbers of rural inhabitants of the territory of Uzbekistan took whatever they had and fled to Iran and Afghanistan. Many held on to the textiles, carpets, and jewelry they brought with them for decades, but many of these household possessions were sold eventually in Afghanistan in the 1970s, when a five-year drought depleted all other resources.

Display of products of Russian-occupied Turkestan, Exposition Universelle de 1900, Paris.

Even after the famines of the 1920s in Uzbekistan, every new Soviet Five-Year Plan called for more and more acreage devoted to cotton. This resulted in increasing use of pesticides and fertilizers with appalling ecological results. As more land needed to be irrigated, larger amounts of water was diverted from the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers that fed the Aral Sea. The resulting shrinkage of the Aral Sea has caused one of the greatest ecological disasters of the 20th century, affecting millions in the region.

Despite periodic uprisings during the initial period of Czarist rule, most conflict was due land seizures by Russian settlers and the 1916 demand for Central Asian conscripts to fight in WWI. Government officials generally supported the more conservative Muslim elite against Central Asian groups such as the Jadids, Muslim modernizers that wanted to change traditional Central Asian society through education.

Bolshevism in Central Asia

Men loading sacks of cotton, UzSSR, photo Max Penson, 1930s.

Local hopes for Central Asian independence ended with the Russian revolution of 1917 that brought Bolshevik power to Central Asia. The Bolsheviks initially promised to liberate all the subject peoples of the Russian Empire. Ultimately, they decided to hang on Russia’s colonies, believing that their “backwardness obliges party organizations to redouble efforts to infuse the workers with Communist ideology by means of widespread agitation and propaganda.” A “Bukharan Bureau” was established in late 1918 to direct propaganda at the “Sarts and Turkestanians” in order to “introduce the backward nations of the East to the socialist way of life.” As part of the Communist program, the Jadids were liquidated in the 1930s in order to eliminate this educated pre-Soviet generation.

New official borders were drawn under the Bolsheviks in 1924. The borders were not drawn along ethnic or linguistic lines, but for political expediency. It was a complicated situation in which the interests of many parties factored. The result, however, was to include Persian speaking regions in Uzbekistan, and to relegate a number of Uzbek-speaking groups to Tajikistan. The major city of Samarkand had been acknowledged in the twenties to be majority Persian; with the next census it officially became nearly 100% Uzbek.[15] A hundred years later, this creates ambiguity in categorizing objects as either from Tajikistan or Uzbekistan, even for experts.

Woman hugging tractor, UzSSR, photo by Max Penson, 1930s.

There is a long history of tension in Uzbekistan between the right of people to own personal property and the right of the State to control it. From 1917 on, wherever there was consolidation of revolutionary power, Bolshevik cadres began looting the homes and possessions of the better off members of Central Asian society. They took garments and textiles, traditional signs of status. In the 1990s, the great Uzbek textile scholar, Sayora Makhkamova, recounted her sadness at not having a traditional munisak robe for her wedding – her family’s textiles had been taken in the 1930s. Another acquaintance, asked if he had any family embroideries, said that yes, he had one. When the Bolsheviks came to search the family home, his grandmother had hidden a folded embroidered suzani wallhanging under her dress, between her legs.

For the Bolsheviks, Uzbekistan and Russia’s other Central Asian possessions were important to showcase as a window on the revolution that would inspire respect and possibly emulation from the outside world. From the very beginning of the revolution, the leadership was acutely aware of the importance of art as a “weapon of ideology.”[16]

The Bolsheviks sought to destroy individual craft production; it was not only considered a form of bourgeoise capitalism to have your own workshop, but the content of the art made there could not be controlled by the State. In 1920, there were about 150,000 artisans registered in Turkestan. More than half of these, 82,150 to be precise, were involved in textile production of various kinds. Under Decree No. 259 of March 16, 1920, all of these artisans became state workers. The workers received their supplies and raw materials from the government and returned the finished goods to the State for distribution. The workers were encouraged to create new designs that reflected the new reality.[17] State control extended into home production as newspaper articles lauded young women for making embroideries in colors disliked by their grandmothers.

The Personal Property of Central Asian Jews

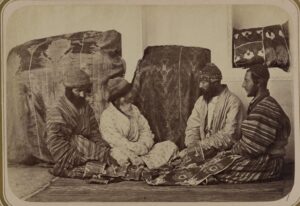

Jewish families negotiating dowry (ikat textiles), Turkestanskii al’bom, Commissioned by Turkestan Governor-General, K.P. von Kaufman, Compiled by A.L. Kun and M.I. Brodovskii. 1871-1872. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs.

Former President Islam Karimov once stated during a formal address to a group of Jews from England that, “Over the course of many centuries of living together with the Jews on the territory that was [to become] our country, there was never a single violent incident directed against the Jewish nation.” This is of course, palpably untrue, and President Karimov’s reference to the Jewish nation as distinct from the Uzbek after at least 2000 years of co-habitation only emphasizes the distinction.

Jews were very important in the commercial life of Central Asia and Jewish records show their involvement in many forms of crafts as well as trade. Although discriminated against, Jews played an important part in the civil and cultural life of the Khanates and later in Soviet Uzbekistan. They were important as court musicians and later in preserving the traditional Shash Maqam musical tradition in Uzbekistan. Jewish women performed for female audiences at Uzbek and Tajik events, danced, sang in Persian and Uzbek, told stories and gave blessings to attendees at weddings and other ceremonial events. Regrettably, after independence, traditional Jewish artists and musicians were often replaced by Uzbeks as part of Uzbek nationalist efforts, discouraging them from staying in the country.

Synagogue decorated with ikats and suzani embroideries, 1932.

The history of Jewish emigration is complex. Jews from Bukhara were some of the first to emigrate to Palestine in the 19th C, founding the Bukharan quarter in Jerusalem. Jews played essential roles in traditional silk textile dyeing and fabric production in Uzbekistan. In consequence, waves of Jewish emigration also occurred after the closing of small businesses and craft shops under the Bolsheviks. Starting in the early 1970s, during the Soviet period, a few Jews were allowed to leave the UzSSR, and during the 1990s, after independence, the majority of the Jewish population left. Today, Jews in many areas of Uzbekistan have difficulty raising a minyan to say Kaddish.

What consequences would a cultural property agreement have on the ability of Bukharan and other Central Asian Jewish communities here in the U.S. Will Jews who have emigrated to the United States not be able to import “traditional Uzbek handicrafts” that their own families made? Will Jews traveling to the U.S. have heirloom goods seized? These are questions not addressed in Uzbekistan’s request for an MOU.

The Modern Era

Post-Soviet ‘Independence,’ Corruption and Policies of Impoverishment

For the older generation of Uzbeks, who saw a lifetime of savings wiped out overnight, this was devastating. Now, with extreme inflation and a virtually worthless currency, many struggled to obtain food and shelter. Some, with their savings decimated, looked to their personal possessions as a way to raise funds.

Traditionally, Central Asians held textiles as a form of wealth and as a necessary element of weddings, circumcisions, funeral, and other family rituals. Old carpets, embroideries, and weavings such as ikats had value on the international market and could have been converted to cash. Unfortunately, in the case of better off, bourgeois families, most of their textiles had already been looted by Bolshevik party members during the upheavals of the 1920s and early 1930s.

Tajik wedding ceremony, Turkestanskii al’bom Commissioned by Turkestan Governor-General, K.P. von Kaufman, Compiled by A.L. Kun and M.I. Brodovskii. 1871-1872. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs.

In the name of “preserving heritage,” the newly independent Uzbek government claimed the right to control the export of anything it deemed of value. The indiscriminate nature of these restrictions had the effect of depriving citizens of the full value of their possessions at a time of greatest need. It is noteworthy that this was also taking place at a time of phenomenal corruption and the looting of billions from the Uzbek economy by Islam Karimov, President of Uzbekistan and his family and of severe repression of dissent of any kind.[18]

In the 1990s, Uzbek citizens still in possession of family heirlooms were unable to access markets outside of Uzbekistan as the government forbid the export of anything over 50 years old. Low prices in the local market benefited buyers with cash and the ability to bypass the Uzbekistan Cultural Ministry by smuggling textiles out of country. To a large extent, the illegal trade was dominated by Turks. In this period of economic freefall, vast quantities of Central Asian antiques appeared in the markets of Istanbul in the 1990s. Most of what had remained of 19th and early 20th C textiles in private hands left the country at that time.

Jewish Funeral, Turkestanskii al’bom (Turkestan Album) Commissioned by Turkestan Governor-General, K.P. von Kaufman, Compiled by A.L. Kun and M.I. Brodovskii. 1871-1872. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs.

Although workshops making handmade textiles were collectivized under the Soviets, there was still an ongoing practice of women making hats, trims and larger suzani embroideries. Thousands of these embroideries, made between the 1950s and 1980s, mostly of indifferent quality and of little interest to serious collectors, were also offered to tourists visiting Uzbekistan. Although less than 50 years old and legal to export, many tourists did not bother to apply for the required export permit and had their treasures confiscated by the Uzbek customs at the airport on departure.

During the mid 1990s to early 2000s, many museum curators protested to the Uzbek customs about the huge customs seizures of textiles, jewelry and other items being brought to local museums, often by the truck load. One curator stated that she had told the customs that there were already superior examples on display and in storage and there was no need or use for what they were bringing.[19] Also, since everything seized by customs needed to be separately cataloged, it drained museums’ limited resources and prevented any ongoing research by museum staff.[20]

While the majority of the confiscated goods could have been cleared through the Ministry of Culture with a permit, this was in fact an extremely burdensome process, even for the most minor or recent material.[21] In any case, due to a lack of public information, most tourists were probably not aware of the laws or had any reason to believe that such minor objects, bought for very little, could possibly have been considered of such importance that their export would be prohibited.

Past Mismanagement and Corruption in Heritage in Independent Uzbekistan

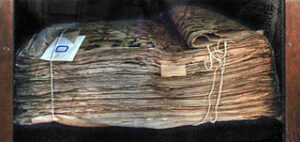

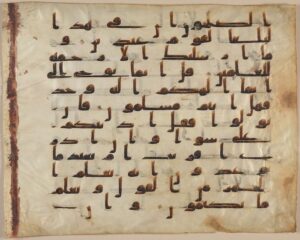

The Samarkand Quran. Said to be the 7th century original of the edition of the third caliph Uthman. Hast-Imam Library.

There is no evidence that there is currently smuggling and illegal export of cultural heritage from Uzbekistan. Uzbekistan’s government has made strides in documenting heritage, including in cooperation with international partners (including the U.S.) and in curbing mismanagement and corruption. There was never a problem of looting of archaeological heritage and the present government has maintained strict control of domestic sale and export of ethnographic art including textiles. A decade ago, there several well-publicized prosecutions of individuals who were jailed for smuggling fairly ordinary ethnographic art objects. The effectiveness of Uzbekistan’s export laws shows that an MOU is neither necessary nor warranted today.

Samarkand Quran, leaf, Metropolitan Museum, New York.

What has not taken place, however, are investigations of past corruption. More than one example of a notorious theft has failed to have been investigated or prosecuted – or if they have been, there has been no public notice.

One of the most important Islamic artifacts in Uzbekistan was not made there but is said to have formed part of the emperor Timur’s 15th C. library. The magnificent Samarkand Qur’an, the remainder of which now rests in the Hast-Imam Library in Tashkent, wasa for centuries thought to have been made for the third Caliph of Islam, ʿUthmān b. ʿAffān (r. 644-656 CE) (and to be marked by blood he spilled, murdered while reading it). Based on more recent analysis, it is from the ‘Abbasid period at the latest. The Qur’an was taken by Russian General Alexander K. Abramov from the Khodja-Ahrar Mosque in Samarkand and sent to the Imperial Library in St. Petersburg in 1869.[22] Based upon facsimiles made in St Petersburg, only about 1/3 of the original leaves, each requiring the vellum from an entire sheep, remained at that time. (Nearly 40 leaves that are missing from the St. Petersburg facsimile that had apparently already been removed in the early 19th century, according to a UNESCO report, and have appeared at various times on the art market.)

Facade of Chashma Ayub Mausoleum with tile missing, near Bukhara.

The Samarkand Qur’an was returned from Petersburg to Uzbekistan in 1917 and was placed in the National Museum until 1989, then moved to the Hast-Imam Library. A dozen original leaves of which facsimiles were made in St. Petersburg were stolen from the Quran after it was returned to Uzbekistan, but only, it appears, after independence in 1991. Some of these appeared in museum collections in Kuwait and Doha and others were auctioned at Christies – starting in 1993, under the government of Islam Karimov.

The theft, sometime in 2014, of a very large, exceptionally fine 14th C tile from the frieze decorating the top of the arch of the entryway to the Well of Chashma Ayyub, the Spring of the Prophet Job, in Vobkent, about 30 km from Bukhara, is another noteworthy example of a theft that must have involved very tightly closed official eyes.

Islamic tile from the Chashma Ayub Mausoleum recovered in the UK. Courtesy The British Museum.

Only an extremely well-connected individual could have removed, exported, and sold pages from the largest, oldest and most important manuscript in the country, or removed an enormous calligraphic tile from high up on the façade of a famous monument, apparently without anyone noticing until the tile was offered for sale in London, only to be immediately identified by an academic, and voluntarily presented to the Uzbekistan Embassy for its return.[23] No one in Uzbekistan has been prosecuted.

The Current Status of Ancient and Ethnographic Objects in the Republic of Uzbekistan

In the last decades Uzbekistan’s cultural heritage system has been professionalized, museums have been updated and inventoried, and theft of antiquities from museums is not the problem it once was.

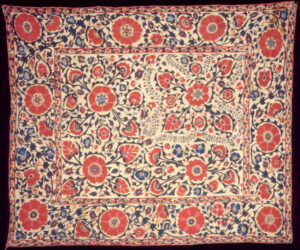

Large embroidered suzani, Shahrisabs, Uzbekistan, 19th C.

If a researcher wants to study Central Asian antique woodcarving, ceramics, manuscripts, metalwork, jewelry or antique embroideries or ikats inside Uzbekistan, he must go to a museum or a monument where they are displayed. Older objects of good quality are rarely held in private collections or offered for sale in markets or galleries. Similarly, the carpets currently sold in Uzbekistan are commercially produced and of no interest to the Western collector.

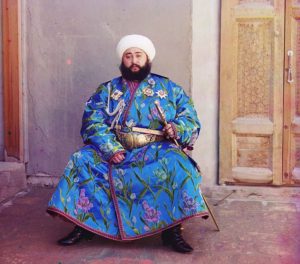

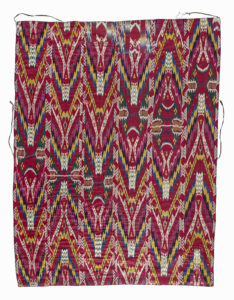

Exceptional quality silk textiles were the primary trade good of what is now Uzbekistan for some 1500 years. In the 19th C, after a period of diminished economic activity of several hundred years, silk production flourished to the point that every mulberry tree in the Khanate of Bukhara was said to be stripped of its leaves to feed silkworms in the spring. Large-scale embroidered wallhangings, robes and horse-trappings, and ikat-dyed silk, half silk and velvet robes and hangings were some of the most valuable and prestigious objects in the Central Asian Khanates. The fabric for a single silk velvet ikat robe took months to dye and weave – and sold for more than the price of a human slave. Smaller and less elaborately constructed textiles were ubiquitous. Traditionally, a stack of embroidered and patterned quilts and hangings was piled to the ceiling in both rural and urban homes. Virtually all women engaged in embroidery whenever they had spare time and male professional embroiderers worked in small craft workshops in major textile producing towns like Bukhara, Samarkand, and Shahrisabs. (The romantic tale that the large scale suzanis were made exclusively by women for dowry and home adornment has been categorically disproven.[24])

Emir Alim Khan of Bukhara (1880-1944), photo Sergei Prokudin-Gorskii, 1911, color slide technique. Library of Congress.

However, these beautiful and valuable 19th C embroideries are not longer to be found in Uzbekistan. They left a long time ago. There are many hundreds if not thousands of 19th and 20th C embroideries in US, UK, European and Russian collections dating to 50-150 years ago. This is best illustrated in a solidly prosaic note in William Eleroy Curtis’ 1911 travelogue, Turkestan, The Heart of Asia,[25] who tells that a Chicago gentleman of his acquaintance who brought back “a very handsome specimen of Bokhara embroidery” from one of his visits to Turkestan, found “an exact duplicate hanging upon the wall of a friend in Evanston,” purchased from a department store in Chicago. The gentleman found fifty more pieces precisely like his own when he went to the store the next day, offered for less than he had paid in Bukhara.

As a result of Russian commerce, Bolshevik pillaging and being taken out of the country by émigrés long ago, these textiles are not to be found any longer outside of inventoried museum collections in Uzbekistan. There are more than enough already in Europe and the United States to satisfy a far larger market than exists today.

Uzbek Recognition of the Value of Foreign Collections and Foreign Scholarship: The Cultural Legacy of Uzbekistan in World Collections Project

Central Asian ikat wall-hanging, Freer-Sackler Galleries, Smithsonian Institution, Gift of Guido Goldman.

In order to assess the positive aspects of previous collecting by foreigners of art from Uzbekistan, it is useful to quote from the Uzbeks themselves. A project to publish some 40 books under the title “Cultural Heritage of Uzbekistan in the World Collections” was initiated in 2019 by well-connected individuals in Uzbekistan’s private sector with the blessing of Uzbekistan’s government. The books from the project, published in Russian, Uzbek and English, are not available for sale. Some are given to international museums contributing to the project, but the effort is primarily intended to enhance the knowledge of the culture of Uzbekistan domestically – among local students and scholars. The initial information sheet for this project, addressed to international scholars and collecting museums, spells out the benefits of the worldwide circulation of the art of Uzbekistan:

“As you know, for a variety of reasons a large number of artifacts were removed from Uzbekistan and are now displayed as part of collections all over the world. On one hand, this appropriation of our cultural heritage by foreign museums can be seen as a loss; on the other hand it is positive, because it means that more people will find out about our culture. Uzbek culture has become widely known outside of our state. People of all backgrounds are drawn towards the art and culture of Uzbekistan: from orientalist academics to ordinary museum visitors. They study and admire art objects from Uzbekistan and grow in respect towards our nation.”[26]

A contemporary ikat made by Rasul MirzaAkhmedov. Credit Binofsha Nodir.

Projects like these, which purposefully incorporate a variety of international perspectives and will encourage dialog among scholars and exchanges between museums, will bring Uzbekistan’s culture and its national heritage to international prominence and encourage cooperative bilateral relationships. They are also far more likely to encourage long-term loans of great art from Uzbekistan and art from other nations to Uzbekistan’s museums. (See Uzbekistan Leads the Way in International Collaboration on Cultural Heritage, Cultural Property News, October 10, 2019)

The Revitalization of the Art of Ikat in Uzbekistan

Perhaps the most extraordinary and unexpected benefit accruing to Uzbekistan through Western collecting of its art is the revival of the lost art of Central Asian ikat. (See A Textile Collector Changes the World: Ikat Exhibitions in DC Show How Global Exchange Revived an Ancient Art, Cultural Property News, April 22, 2018.) This silk textile craft involved a combination of artisans including Jewish, Uzbek, and Tajik dyers and weavers. Central Asian ikat reached its height in the early to mid-19th century. Under Soviet rule, however, persecution of individual craftspeople and consolidation of workers into ended true ikat weaving.[27]

Almost 90 years later, a comprehensive publication on Central Asian ikat and series of exhibitions in major U.S. museums sparked the interest of Oscar de la Renta, Armani, Gucci, Alexander McQueen and other top designers.[28] Weavers in the Ferghana Valley of Uzbekistan were first inspired to try to make forgeries and then to openly replicate the beautiful 19th C fabrics. A hitherto virtually unknown style of resist textile design was suddenly in demand everywhere. Beautiful ikat textiles identical to mid-19th C production are now being made by hundreds of craftsmen and women in Uzbekistan, and printed copies of Central Asian ikat fabrics are ubiquitous in worldwide textile production.

Almost 90 years later, a comprehensive publication on Central Asian ikat and series of exhibitions in major U.S. museums sparked the interest of Oscar de la Renta, Armani, Gucci, Alexander McQueen and other top designers.[28] Weavers in the Ferghana Valley of Uzbekistan were first inspired to try to make forgeries and then to openly replicate the beautiful 19th C fabrics. A hitherto virtually unknown style of resist textile design was suddenly in demand everywhere. Beautiful ikat textiles identical to mid-19th C production are now being made by hundreds of craftsmen and women in Uzbekistan, and printed copies of Central Asian ikat fabrics are ubiquitous in worldwide textile production.

Similarly, recognition of the beauty and value of the early silk embroidered suzani inspired first forgeries and then the making of thousands of new suzanis emulating19th C design. Many of these reproductions would defy the ability of a customs officer to distinguish between the new and the old, for they are made in the exact same techniques, by hand, often using natural dyes.

Conclusion

As stated above, any agreement with Uzbekistan should be conditioned exclusively on meeting the requirements of U.S. law.

The request today is not a plea for U.S. assistance in ameliorating a situation of current looting. It is the latest expression of the right of the Republic of Uzbekistan to exercise State control over private property – down to postcards, or even a postage stamp. The United States does not share this perspective, but Uzbekistan has the right to make the rules for its own citizens. That does not mean that the United States should endorse such a policy – one that would not pass constitutional muster here.

A better relationship with Uzbekistan is desirable, of course, as is Uzbekistan-American friendship and cultural cooperation. Cultural cooperation should be based on the realities and the actual needs of Uzbekistan’s cultural sector for assistance in conservation and programs for public education, not by entering into an agreement intended to stop looting, when the legal justification for the agreement does not exist.

Notes

Map of Tartary.

[1] Uzbekistan is seeking import restrictions on “archaeological material dating from the Paleolithic period (50,000 BCE) to the 18th century CE and including the following periods, styles, and cultures: Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic, Ancient Bactrian, Korezm/Khorezm, Seleucid, Kangjiuy, Kushan, Greco-Bactrian, Ephthalite/Hephthalite, Turkic, Somanite/Samanid, Karakhanid, Korezmsakh/Khorezmsakh, Mongol, Timurid, Bukhara, Kiva/Khiva, and Uzbek periods. This material includes stone; ceramics, faience, and fired clay; metal; plaster, stucco, and unfired clay; painting; ivory and bone; glass; leather, birch bark, vellum, parchment, and paper; textiles; wood, shell, and other organic material; and human remains.”

“Requested ethnological material date from the 7th century CE to 1917 CE and come from the Early Islamic, Middle Islamic, and Uzbek periods. This material includes weapons of historical, artistic, scientific and other cultural value; artworks containing precious metals and precious stones; objects and their fragments; completely handmade paintings and drawings on any basis and from any materials; sculptural works made of any materials, including relief paintings; original artistic compositions and montages made of any materials; artistically decorated objects for the purpose of worship; engravings, prints, lithographs, xylographs, other types of graphics and their original printed forms; practical and decorative works of art (art objects made of glass, clay, wood, metal, bone, fabric and other materials); traditional folk arts and crafts; components and fragments of architecture, history, artistic monuments and monumental art monuments; books, as well as printed works of historical, scientific, artistic, and literary significance; unique manuscripts and documentary monuments, archival documents; musical instruments; coins, bonistics, orders, medals, seals, postcards (envelopes), postage stamps, numismatics, phaleristics, and other collectibles; objects important for branches of science such as mineralogy, paleontology, anatomy; household and scientific equipment and tools; and other movable objects, including copies of historical, scientific-artistic or other cultural significance, as well as copies protected by the state as historical and cultural monuments.” Cultural Property Advisory Committee Meeting, January 30- February 2, 2023, https://eca.state.gov/highlight/cultural-property-advisory-committee-meeting-January-30-February-02-2023

[2] 19 U.S.C.§ 2601 (2)

[3] Id. § 2602 (a) (1).

[4] Id.

[5] As the Senate Committee Report explains, “The Committee intends these limitations to ensure that the United States will reach an independent judgment regarding the need and scope of import controls. That is, U.S. actions need not be coextensive with the broadest declarations of ownership and historical or scientific value made by other nations. Senate Report 97-564 at 6 (1982).

[6] The Central Asian Bronze Age was first discovered by an American, Raphael Pumpelly, in the early 20th century, but his investigations were cut short by the arrival of the Bolsheviks. It was rediscovered and its scope vastly expanded in large part through the work of Greek-Soviet archaeologist Victor Sarianidi in the 1970s – 1990s.

[7] Despite the poor storage facilities for excavated wall paintings personally seen in Samarkand in the 1990s, where fragments of painted plaster lay on the floor of a damp storage room, this material remains in Uzbekistan. Western and Indian collections of similar materials (primarily from Xinjiang) were collected in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, by archaeologists such as Sir Aurel Stein.

[8] S.D. Goiten, The Documents of the Cairo Geniza as a Source for Mediterranean Social History, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 80, No. 2 (Apr. – Jun., 1960), pp. 91-100. Note: During research at the Samarkand Museum in the 1990s, a researcher was informed that a lightweight silk robe on display was the only Timurid period textile in the museum’s collection. It was raining at the time, the roof was leaking, and there was a bucket standing next to the vitrine that held the garment. Personal communication to authors.

[9] The “Khivan Archive” was ‘lost’ for decades, then rediscovered in Russia. Paolo Sartori, “Khiva 1873: The “Archive” That Never Was, QUADERNI STORICI 167 / a. LVI, n. 2, August 2021, p 443, https://www.academia.edu/66096968/KHIVA_1873_THE_ARCHIVE_THAT_NEVER_WAS

[10] In 1965, Bregel had sharp words for the practice of moving documentary materials back to Uzbekistan: “Bregel noted that ‘the Central State Archive of the UzSSR stubbornly secured the transfer of the documents from Leningrad, claiming that they represent a national heritage (natsional’nym dostoianiem). [I must observe, however,] that this national heritage is kept incomparably worse than it was stored in Leningrad, and that access to these documents for scholars is now made more difficult than it was in Leningrad’.”Id., pp 443-44.

[11] Sartori writes, “In 2017 the “Archive of the Khans of Khiva” was officially included into the UNESCO Memory of the World Register, a site that «lists documentary heritage» chosen according «to the selection criteria regarding world significance and outstanding universal value». This is no doubt an important recognition that increases international interest in the documentary material preserved in Uzbekistani archives and puts into greater relief the history of pre-colonial Central Asia. At the same time, UNESCO’s conferral of distinction upon the “Archive of the Khans of Khiva” is today deployed in Uzbekistan for other purposes. It facilitates the nation-state’s claim of patrimony over records produced in Qonghrat-ruled Khorezm. At the same time, it assists Uzbek scholars and government officials in the task of grafting the notion of a centralized state archive onto the history of the Khanate of Khiva. One cannot help but noting that to state as Uzbek archivists today do that such records offer “evidence of the degree of evolution of statehood […] of the Khanate of Khiva” is tantamount to creating an artificial continuity between the khanates and the Uzbek nation state, misinterpreting the pre-colonial history of the region, and misleading anyone interested in uncovering the specifics of Central Asian documentary practices.” Paolo Sartori, supra note 10, “pp 462-63.

[12] 19 U.S.C. § 2601 (2)(C)(ii)

[13] Annette Meakin, In Russian Turkestan, The Garden of Asia and Its People, G. Allen, London, 1903, pp 42-43.

[14] Even Dostoyevsky perpetuated these illusions: there is a discussion about a newspaper story about Muslim fanatics skinning a Russian soldier taken prisoner who refused to renounce Christianity in The Brothers Karamazov.

[15] Uzbekistan’s first President, after the fall of the Soviet Union, Islam Karimov, spoke only Persian and Russian. He and other officials (including the Ambassador to the US and all his staff) had to take crash courses in the Uzbek language.

[16] From their first days, the Bolsheviks had a willing and immensely talented pool of artists and designers to draw from. El Lizzitsky, Alexander Rodchenko, Kasimir Malevich, Mark Chagall, Vladmir Tatlin and others actively collaborated with the authorizes during the first years of the revolution. Their revolutionary art was too much for the middle-browed tastes of Stalin and was banned for its sin of “formalism.” Socialist Realism officially began in 1932, when a Stalinist decree ordered the dissolution of all artist unions with their endless bickering over what was an appropriate “revolutionary” style. Art became a “weapon of class struggle” entirely at the service of the state.

[17] In 1933, Pravda published an article called “Tractor in Front, Combine Harvester Behind” which subjected the latest “revolutionary designs” to withering criticism. It asked whether the artists responsible for them might not secretly be “class enemies, who are attempting with calico and flannelette to make us into laughing-stocks. Nobody has the right to turn you, the honest worker, into a walking picture gallery,” the newspaper said. “Here’s a brand new, brightly colored cotton fabric with pictures of big tractors and big combine harvesters. As you walk down the street, your body is tightly wrapped in a collective farm with an agricultural motif. You meet someone on the street dressed like that – with a tractor in front, combine harvester behind – and you immediately mobilize yourself to go off to the fields and battle for your crops. And here’s a nice fabric for pajamas. Once again: not some objectless pattern, not just idealistic nonsense, but the whole story of Turksib. A camel caravan wanders over the yellow sand. A herd of sheep shows up black in the background. In the middle, a train steams by. How nice to sleep in such pajamas. You sleep, and a train steams over you. You turn over, and sheep are grazing. You lie on your stomach, and camels march on top of you. You’re lying down but you’re not wasting time – you’re learning about the distant lands which used to be oppressed by czarism. What an educational sleep!”

[18] Uzbekistan’s long-term President, Islam Karimov, died in September 2016. According to Human Rights Watch, “During Karimov’s over 26-year rule in Uzbekistan, authorities detained thousands of people on politically motivated charges, routinely tortured those in prison and police stations, and forced millions of citizens, including children, to pick cotton in abusive conditions. On May 13, 2005, Uzbek government forces shot and killed hundreds of largely peaceful protesters in the city of Andijan, for which no one has been brought to justice.

“Islam Karimov leaves a legacy of a quarter century of ruthless repression,” said Steve Swerdlow, Central Asia researcher at Human Rights Watch.” Uzbekistan: Authoritarian President Karimov Reported Dead, Human Rights Watch, September 2, 2017, https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/09/02/uzbekistan-authoritarian-president-karimov-reported-deadSee also Human Rights Watch, World Report 2022, Uzbekistan, https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2022/country-chapters/uzbekistan

[19] One curator illustrated this by showing a visiting researcher a museum closet crammed to the ceiling with old metal household irons that used hot coals. Personal communication from Uzbek curators, circa 2000.

[20] Personal communication from Uzbek curators, 1994-2004.

[21] An appointment needed to be made, photographs and other details of the items provided and a cash payment made for each item. Although the payment itself was not large-usually between $10 to $30, it was often equal or greater than the purchase price. Also, during the frequent currency shortages the demand for a cash payment in soum for the permit would be impossible for tourists to fulfill as there was no Uzbek currency available in hotels, banks or market exchanges. The Ministry of Culture did not accept credit cards or foreign currency of any type.

[22] Elleonore Cellard, “The Samarkand Qur’an,” The Arabic Script and Its Past, Ed. Ahmad al-Jallad and Ahab Bdaiwi, 2022 (pre-publication copy) https://www.academia.edu/92792929/The_Samarkand_Quran

[23] British Museum helps return stolen artifact to Uzbekistan, The Guardian, July 17, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/jul/17/british-museum-helps-return-stolen-artefact-to-Uzbekistan.

[24] See Fitz Gibbon and Hale, Uzbek Embroidery in the Nomadic Tradition, Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 2007, pp 130-162.

[25] William Eleroy Curtis, Turkestan, The Heart of Asia, (New York,: Hodder and Strouton, 1911) 172-173.

[26] Information Sheet for contributing scholars to the project ‘Masterpieces of Uzbekistan in the collections of the world cultural heritage.’ 2019. Noteworthy among the collecting museums mentioned are more than 20 Russian museums. Among them are the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts, Russian National Library, the Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, the State Tretyakov Gallery, the Russian Museum of Ethnography, and the All-Russian Museum Association of Musical Culture named after Glinka.

[27] Although in the early 1990s, Uzbek scholar Sayora Mahkamova made a number of attempts to train craftspeople to replicate traditional ikat designs, the attempt was not successful.

[28] None of Dr. Goldman’s 400 ikats were collected in or directly from Uzbekistan; all were found in European or American collections originally sourced in Afghanistan in the 1970s, preserved among the textile wealth of emigres from the early 20th C to Afghanistan.

Detail, Charles Robertson, A Carpet Seller, Cairo, photo courtesy Sotheby's.

Detail, Charles Robertson, A Carpet Seller, Cairo, photo courtesy Sotheby's.