And on the pedestal, these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

Ozymandias, 1818, Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792–1822)*

It is one of the clichés of history that an empire rises only to fall. All imperial powers, from the Romans to the Soviets, have met their limits, waned and failed. As in Shelley’s Ozymandias, their works of art and architecture remain to recall the lost greatness of past empires, a warning to future kings and conquerors of the ephemeral nature of all achievement – excepting only art.

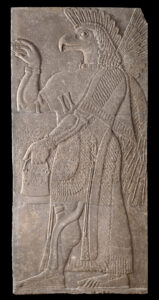

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the third of many successive empires to reign over an area now divided between Iraq, Iran, Syria, Jordan, and Lebanon, from the 10th to the 7th century BCE. The heart of their territory was the region sometimes called the Fertile Crescent, watered by the Tigris and the Euphrates. Along these rivers arose the grand palace complexes from which the Assyrian emperors controlled their territory and directed further conquests.

Their last capital, Nineveh, was once the greatest city on earth. During the rule of Ashurbanipal (668-c. 626 BCE), one of the last kings of Assyria, great works of monumental architecture rose in stone in what is now northern Iraq. An inscription found at the site declared him ‘king of the world, king of Assyria;’ a grandiose claim, but one validated by the magnificence of his capital.

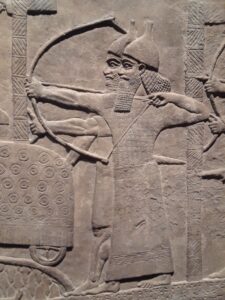

Relief panel, Detail of attack on an enemy town, Assyrian, 730-727 BC, Kalhu (Nimrud), Central Palace, reign of Tiglath-pileser III, British Museum. The Getty Villa, Pacific Palisades, CA.

The wealth of Nineveh was founded upon its kings’ military might, their relentless expansion of their territories and their ruthless exploitation of the peoples they conquered. Ultimately these same factors, abetted by a decades-long drought across much of the once-fertile Assyrian heartland, led to the collapse of the empire. Only a few decades after the death of Ashurbanipal, Nineveh fell to the combined armies of Babylonians, Persians, Scythians, and others. These peoples had long paid tribute to their Assyrian conquerors in material goods, and human labor, before rising up to destroy those who once controlled them.

Today, relatively little remains of Nineveh, Nimrud, or the other great cities and palaces built by the Assyrians. The destruction wrought by the wars of two-thousand and more years ago was followed by a long period of literal obscurity, during which the ruins of cities and palaces lay buried in disregarded mounds. Excavations began in the nineteenth century, and study of the sites continued, with interruptions into the twenty-first century. The looting of the Baghdad Museum in the wake of US-led strikes on the city in 2003 led to the loss of major artifacts recovered from the Assyrian sites. This catastrophe was exacerbated by the 2014-2017 occupation of the region by ISIS, when, tragically, the ruins of Nineveh and Nimrud were deliberately destroyed by soldiers with hand tools and bulldozers. Today, all that survives of these sites as they once were, are photographs and drawings produced by archaeological teams, along with those sculptures, reliefs, and wall-decorations which were in foreign museums at the time of the sites’ capture.

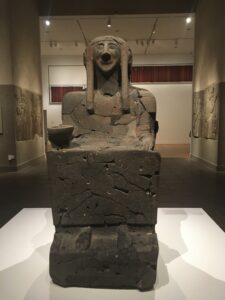

Seated figure, Neo-Hittite, ca. 10th-9th C BCE, Tell Hallaf (ancient Guzana), Syria, Max Freiherr von Oppenheim Foundation, Cologne. Reconstructed statue shattered in Allied bombing of Tell Halaf Museum in Berlin in WWII. Metropolitan Museum, NY. CCP photo.

Some of the most striking remnants of the ancient Assyrian empire are currently on display in two notable exhibitions, at the Getty Villa and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Meanwhile an installation of the work of Iraqi-American artist Michael Rakowitz, inspired by and in memory of the lost archaeological remains at Nineveh, is on view at the Williams College Museum of Art.

All three exhibits are examples of museums’ capacity to not merely recount the history of artifacts, but to bring forth new stories about what these objects have meant to many nations, in a global context and over time. The reliefs in these exhibitions are the survivors of one imperial collapse, and their journeys through time and across the globe to their host galleries have been determined largely by the conflicts and collaborations between nations with their own aspirations to global power.

These exhibitions are also a display of a different kind of globalizing force; the emergent trans-national community of art and history museums. The displays at the Getty Villa and the Metropolitan are made possible by loans between institutions; thirteen of the Nineveh plaques on display at the Getty Villa belong to the British Museum, while the Pergamon Museum in Berlin has loaned a famous figure from another Assyrian site to the Met for the show. This open-handed sharing of artifacts introduces a new theme into the history of objects that have been bought, sold, seized, bombed, and lost, but only now have become part of global heritage, protected from harm and able to cross borders and bridge cultural divides. The stone reliefs and sculptures are part of the legacy of civilizations and culture that are under attack in modern times, giving Iraqi and Syrian people in diaspora access to their cultural heritage.

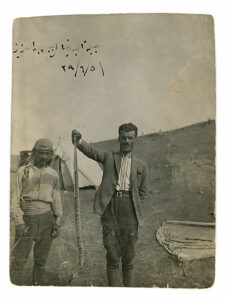

Photograph of the artist Rayyane Tabet’s great grandfather, Faik Borkhoche, holding a snake. photo Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY.

The Met’s exhibition puts a personal emphasis on the story of the lost and found artifacts on display, by framing them as part of the family history of contemporary artist Rayyane Tabet. His great-grandfather was a Lebanese secretary who worked on an Aramaean site called Tell Halaf in the 1920s and ‘30s. The Aramaean peoples lived at the Western extreme of the Assyrian territories. Their city-states once functioned as independent satellites of the Assyrians, until military campaigns in the 9th or 8th century annexed them to the empire proper.

Among many other extraordinary finds at Tell Halaf were over a hundred stone relief panels, much like those recovered from the remains of Nineveh, though predating them by several centuries. Their discovery, excavation, and exportation by a German baron-archaeologist are entwined with the politics of European activities in the Near East in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and with Tabet’s own family history. Baron Max von Oppenheim made his first observations at the site of Tell Halaf 1899, when the area was still under the control of the Ottoman Empire, and von Oppenheim was meant to be surveying routes for a German-sponsored railroad route to Baghdad. The outbreak of the first World War interrupted the excavations for which he only obtained Ottoman permission in 1912 – when he returned, in 1927, the Ottoman Empire had collapsed, its territories divided between European colonizing countries. Tell Halaf was inside the region under French Mandate control. Tabet’s grandfather was not just a secretary to the Baron – he was also a counter-spy, appointed by the French government to observe his activities, and to ensure that he was not engaged in mapping the territory to facilitate a German takeover, under cover of his excavation work.

Stone reliefs, Tell Halaf. Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY. CCP photo.

Despite his French authorization, the largest share of the finds from the site went to Oppenheim’s own foundation in Berlin, Germany. German expansionism soon provoked the outbreak of World War II, in the course of which the building housing Tell Halaf’s artifacts was bombed, reducing the reliefs and statuary inside to rubble. The shattered pieces were carefully crated up and transported to another museum for safe-keeping until they could be reassembled, but the post-War division of Berlin marooned the boxes on the East side of the Berlin wall, while Oppenheim’s museum was left almost barren on the West side, unable to access its damaged collection pieces until 1990, when careful reconstruction of the objects began.

The Met’s exhibit tells the story of these objects, not just as antiquities, but as survivors many times over, testaments in stone to the resilience of art and of the preserving power of the value we place on our human cultural heritage. The reliefs found on the wall of Tell Halaf are now spread across five countries, with the majority in Berlin and Aleppo, in which latter city Oppenheim’s finds formed the core of the then-newly founded National Museum. We can only hope that those in Aleppo make it through the ongoing conflict in that nation intact.

The stone reliefs on display at the Getty Villa form part of a more traditional exhibition, one focused on educating visitors about the history of the reliefs and meaning of the images.

This exhibition, too, recalls the archaeological work that led to the artifacts’ discovery and preservation, albeit in less sensational terms than the “spy story” told by Tabet. The objects are accompanied by a series of drawings of the site during excavations at Nimrud and Nineveh by Sir Austen Henry Layard, who excavated several of the reliefs on display between 1845-1851. Layard’s own work was supported and permitted by another 19th century imperial power: Great Britain. Fittingly, the reliefs illustrate many of the activities that contributed to the might of the Assyrian emperors: war, the receipt of tribute, and ceremonial lion hunts that glorified the king of Assyria as a mighty warrior.

The reliefs are now the property of the British Museum, one of the greatest of the world’s museums, a treasure house of antiquities open to tourists, art lovers, and scholars from across the globe. Although there are many ongoing controversies over objects in the British Museum’s collections, these works at least are lucky to have been preserved from the ravages of ISIS.

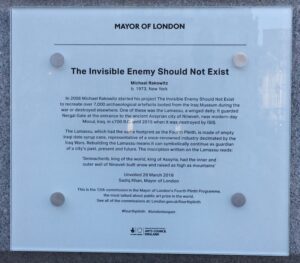

Plaque in Trafalgar Square for ‘the invisible enemy does not exist’, by artist Michael Rakowitz.

Contemporary artist Michael Rakowitz, meanwhile, is working to memorialize those objects that were lost during the US-led invasion from the Baghdad Museum, as well as those destroyed by ISIS at Nineveh and Nimrud. Since 2018, his life-size recreation of one of the massive Lamassu statues at Nineveh, a human-headed, winged bull, has stood on the fourth plinth at Trafalgar Square. Unlike its ancient stone original, Rakowitz’s Lamassu is made from empty date-syrup cans, packaging which commemorates the once-thriving Iraqi date industry, which collapsed in the course of the Iraq War.

Trafalgar Square is one of the most heavily trafficked spaces in London, and, like the palaces of the Assyrians, is furnished with monumental sculpture celebrating the military might of the nation, once the heart of an empire. It is a wide plaza fronting the National Gallery with a statue-topped pillar at its center, topped by a statue of Lord Nelson, the naval hero who led the British fleet to victory over the forces of Emperor Napoleon at Trafalgar, though he died in the battle.

The Lamassu is just one object from a long-running project of Rakowitz’s, entitled The invisible enemy should not exist. His aim is to recreate, in packaging from Iraqi products, all of the seven thousand objects still missing from the Baghdad Museum collections; the damage wrought by ISIS has inspired him to add Nineveh and Nimrud to his commemorative project.

Michael Rakowitz, the invisible enemy should not exist, Trafalgar Square, London, 2018, photo CPN.

An installation of his work is currently on view at the Williams College Museum of Art, in Williamstown, MA. They are set on surfaces erected to exactly mirror the configuration of the walls of Room Z of the Northwest Palace of Nimrud, as they stood before ISIS’s attack on the site. On these surfaces are relief panels, made, like the Lamassu, from the wrappers on Iraqi products, representing the stone carvings left at the site at the time of its destruction. The colorful packaging materials recall the original polychrome appearance of the reliefs; the gaps on the walls between his sculptures evoke the blank spaces left at the original site by the removal of panels for exhibition abroad.

Curators at WCMA have deliberately placed Rakowitz’s installation in conversation with two Assyrian relief panels, gifted to the museum in the 1840s by the British excavator Layard himself, now among the dozens of objects around the world that are preserved in exile.

Relief from the Northwest Palace of King Ashurnasirpal II, acquired by Dwight W. Marsh, Williams College Class of 1842 from the excavator, Sir Austen Henry Layard. Williams College Museum of Art (WCMA), Williamstown, MA USA.

Layard’s gift to WCMA, via an alumnus of the college, can be seen as prefiguring, far in advance, the emergence of a globalizing – not imperial – power which now holds sway over these ancient reliefs. In this century, no rising empire but an expanding community of great museums has dedicated itself to the task of public education and the preservation of art and cultural history worldwide. Internationally touring exhibitions, or international loans, have enabled local museums to share the wonders of world art with their publics, to reconnect diaspora communities with their cultural inheritance, and to keep the artistic survivals of dead empires safe, admired, and understood, as they were in the days of their making.

The losses sustained at Baghdad, Nimrud, and Nineveh, and elsewhere in ISIS-invaded regions, can never be undone. However, widespread dismay at the destruction demonstrated our shared desire to protect the beautiful, awe-inspiring, and informative remnants of humanity’s ancient history, wherever they may be found. These three exhibitions demonstrate the resilience of art in the face of history, and our capacity to continuously re-evaluate past practices and form new understandings of cultural property and its place in the world.

We know this: the lives of empires are cyclical, but art keeps moving forward.

The exhibitions:

Assyria: Palace Art of Ancient Iraq, At the Getty Villa, Pacific Palisades, CA USA, October 2, 2019–September 5, 2022

Alien Property, Rayyane Tabet, The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Met 5th Avenue) New York, NY USA

The invisible enemy should not exist , room z Northwest Palace of Nimrud Michael Rakowitz, Williams College Museum of Art, Williamstown, MA USA, September 27, 2019- April 19, 2020

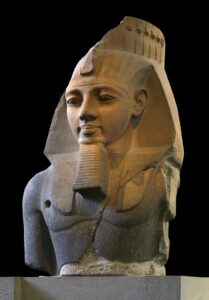

The Young Memnon, The British Museum, London, UK, © The Trustees of the British Museum

* The poet was said to have been inspired by the news of the acquisition by the British Museum of a massive fragment of a stone statue of Rameses II. ‘The Younger Memnon’ is a monumental statue of Ramses II (one of a pair placed before the door of the Ramesseum).

(Many thanks to guest author Mariam Hale. Ed. note: I recently encountered two Iraqi-American teens and their father visiting the lamassu at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and asked what they thought about having these massive sculptures, emblematic of Iraqi culture, in New York. Their response: “It’s great! Otherwise they would be destroyed.”)

Lamassu in front of installation of exhibition 'Alien Property' by Rayyane Tabet, Metropolitan Museum, NY.

Lamassu in front of installation of exhibition 'Alien Property' by Rayyane Tabet, Metropolitan Museum, NY.