The Ethiopian government announced that it is seeking the return of a sacred object in Westminster Abbey, called a tabot, that was looted from an Abyssinian church after the battle of Maqdala (also known as Magdala) in 1868. Tabot are tablets made of either wood or stone, and often inscribed. Tabot are not considered suitable for public viewing; they are held to be symbolic renderings of the Ark of the Covenant and tablets of Moses on which the Ten Commandments were inscribed.

The request to a religious institution that is categorized in Britain as a Royal Peculiar under the jurisdiction of the monarchy, adds a new element to an already complex situation, and returning the tabot may require the consent of the Queen.

Canaletto, The Interior of Henry VII’s Chapel in Westminster Abbey, early 1750s. [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

Ethiopia’s ambassador to Great Britain, Hailemichael Aberra Afework, called for the return of the tabot to Ethiopia, stating that it should be given to an established church there, as it would be inappropriate to exhibit a tabot in a museum.

Other objects from the British punitive expedition into Abyssinia have found their way to museums and other secular British institutions over time. These, and other historical items have recently been claimed by the Ethiopian government.

During 2018, several British institutions chose to exhibit Ethiopian art and artifacts to mark the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Maqdala, in what was then Abyssinia, in 1868. Exhibitions at the British Museum, British Library, and Victoria and Albert Museum have deliberately used the objects to illuminate the history of the Ethiopian conflict, which resulted in tremendous human losses among the Ethiopian troops, who were fighting with spears against rifles, the suicide of Ethiopian Emperor Tewodros II, and the looting of palace and churches by victorious British troops in its aftermath.

Dress, around 1860, Ethiopia. Museum no. 399-1869. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

The museums hoped that bringing forward the truth about the 1868 British punitive expedition would involve the public in a serious discussion about the objects and their history. As it happened, the institutions got more of a response than they expected.

CPN wrote earlier this year about new developments in negotiations between British museums and African nations which claim ownership of artworks in their collections. (See Cultural Property News, Returning African Heritage from Global Museums, April 14, 2017, and Ethiopia: We Want Our Art Back, Not Long Term Loans, May 15, 2018.)

Tristram Hunt, director of the V&A, had committed to sending a number of objects back to Ethiopia on long term loan and to establishing a cooperative relationship for continuing art exchanges between Britain and Ethiopia. Hunt noted that the looting of Magdala was so appalling that it had offended Victorian political sensibilities. (Prime Minister William Gladstone had expressed deep regret that the objects had been seized, and advised that they be returned to Ethiopia as soon as possible.)

The Ethiopian government had initially responded positively to Dr. Hunt’s idea of sending the objects back as long term loans from the V&A. There was change of political leadership in Ethiopia within a few weeks of the Magdala exhibition opening, however, and Ethiopia’s Ambassador to the UK walked back his more conciliatory remarks and announced that the new government was not interested in loans – it wanted the looted objects from Maqdala back unconditionally.

Finding a positive solution to the Ethiopian claims will not be easy. The issues are also made more complicated because of the different circumstances in which the objects held in British collections were acquired. Many were clearly looted by British troops in war – a circumstance which today is not only seen as reprehensible, but is a violation of numerous international conventions and principles of law.

However, the current owners – museums, libraries, and churches – are subject to laws and charters governing management of their collections that did not foresee deaccessioning of collections or anticipate that sacred items in their possession for over 100 years would be deemed stolen.

Front cover of the Life and Acts of St. Takla Haymanot, one of the most revered saints of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. 18th century, British Library (BL Or. 728).

Additionally, not all Ethiopian objects in England were taken in military conquests. Other objects in the various museum shows had a more mixed history. The exhibition, African Scribes: Manuscript Culture of Ethiopia, at the British Library, includes a number of the 349 manuscripts taken from Maqdala as loot, but others at the British Library were acquired as early as 1753. The Church of England Missionary Society donated seventy four Ethiopian codices collected by the missionaries Carl Wilhelm Isenberg and Johann Ludwig Krapf in the 1830s and 1840s during their travels to the little known kingdom of Shewa or Shoa.[1] The overall collection is extraordinarily rich. For example, the library has 110 illuminated Ethiopian manuscripts that contain over 3000 painted miniatures.

As in the case of the tabot, Ethiopian representatives have more than once sought the return of at least the manuscripts that were taken from Maqdala. Girma Wolde-Giorgis, a former president of Ethiopia, wrote in 2008 to the various museums and the British library demanding repatriation of more than 450 objects taken after the battle.

The several exhibitions of Ethiopian art and culture in Britain at this time are also changing the public perception of the Ethiopian nation and its culture. Eyob Derillo, curator of African Scribes: Manuscript Culture of Ethiopia at the British Library said that the sophisticated and beautiful manuscripts in the exhibition were eye-opening:

“Most western [audiences] see Ethiopia as a country of just poverty and dependent on aid. Ethiopia’s rich literature is known for its breadth, depth and longevity. Its origin, the indigenous ideas and creative force that underpin it, as well as the external influences that fed into it and helped shape it have all inspired interest and scholarship.”

Chalice made by Walda Giyorgis in Gondar, Ethiopia, 1735-40. Museum no. M.26-2005. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

As part of its continuing public outreach, the British Library has also made its Ethiopian manuscript collection a major element of its “Heritage Made Digital” program for the next four years to make thousands of documents available online.

While no resolution is in sight, all involved have expressed the hope that there will be positive results from the private discussions between governments and institutions, and that the public’s appreciation of both exhibits and the goodwill that inspired them will lead to further future cooperation.

[1] A difficult person, Isenberg tangled with the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and was in part responsible for the subsequent expulsion of the entire Mission from Ethiopia. Isenberg and Kraft were both linguists, and Isenberg compiled a dictionary and comprehensive grammar of the Amharic language and translated the Scriptures into several African languages.

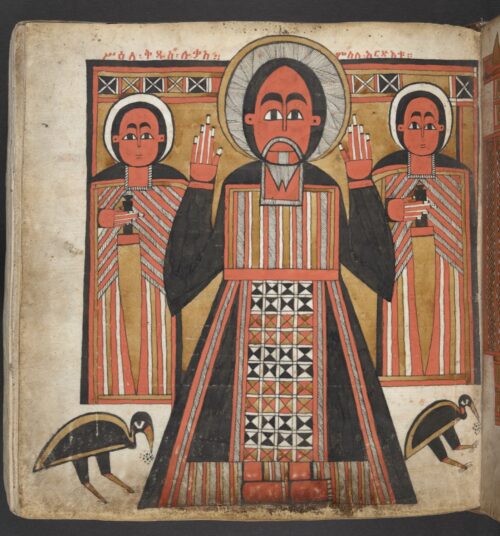

St. Luke the Evangelist accompanied by two disciples. At his feet are two Abyssinian ground hornbills. Ethiopia, Lasta, early 17th century, British Library (BL Or. 516, f.100v)

St. Luke the Evangelist accompanied by two disciples. At his feet are two Abyssinian ground hornbills. Ethiopia, Lasta, early 17th century, British Library (BL Or. 516, f.100v)