UPDATE! The CPAC hearing on renewal of MOUs with Italy, Chile and Morocco and a new proposed MOU with Vietnam is now scheduled for May 20, 2025! Despite the manifold changes at the Department of State, this particular committee’s operational staff and its appointed members, representatives of the fields of archaeology, museums, the art trade and the public interest appears to have continued unchanged.

The public may provide written comment in advance of the meeting and/or register to speak in the virtual open session scheduled for May 20, 2025, at 2:00 p.m. EDT.

How to submit written comments: After weeks of problems and broken links on the Federal Register site, we’ve been informed that it is now working. Use the following link:

https://www.regulations.gov/document/DOS-2025-0003-0001. Please follow the prompts to submit written comments. Written comments must be submitted no later than May 13, 2025, at 11:59 p.m. EDT.

How to make oral comments: Make oral comments during the virtual open session on May 20, 2025 (instructions below). Requests to speak must be submitted no later than May 13, 2025, at 11:59 p.m. EDT.

Please see our Testimony to Cultural Property Advisory Committee at the Department of State.

Vietnam’s Request for a Cultural Property Agreement and U.S. Import Restrictions on Vietnamese Cultural Goods.

Ha Long Bay, photo Francesco Paroni Sterbini, CCA 3.0 license.

CPAC’s May 20, 2025 meeting will also vote on a new request for cultural property import restrictions from Vietnam. According to the announcement for the meeting posted on the State Department website, Vietnam seeks U.S. import restrictions on archaeological and ethnological materials from Vietnam for a period of approximately seventy-seven thousand years, from the Paleolithic to 1945.

The request for restrictions covers virtually every object made by human hands, including objects made from gold, silver, ceramic, stone, metal, copper, bronze, iron, bone, horn, ivory, gems, silk and textiles; lacquerware and wood; bamboo and paper; glass; coins; and painting and calligraphy.

Vietnam’s one-party Socialist Republic passed new cultural heritage laws just this year. Its government espouses Marxism/Leninism and Hồ Chí Minh Thought. At the same time, Vietnam has allowed wealthy citizens to build private museums – filled with goods the U.S. cannot import – and turned temples and sacred spots into tourist havens.

Vietnam’s government’s motives in seeking import restriction can be seen as politically and economically grounded. It seeks the domestic support of its people, who are proud of a lengthy imperial history and the perception of U.S. blessings on its government, rather than preservation of heritage, which is clearly not at risk. And it seeks to exploit its cultural riches for the development of tourism

But this comes at a cost to U.S. citizens. Should Vietnam’s socialist government have exclusive access to traditional culture by Vietnamese-American citizens who escaped Vietnam and want to see its history honored in American museums?

Repatriation campaign

Hoi An, courtesy UNESCO.

Vietnam is actively pursuing the repatriation of historical artifacts up to 1945 to prevent their export. At the same time, private collectors and museum initiatives, including two newly inaugurated museums in Ho Chi Minh City, are evidence that Vietnam’s government will allow its citizens to collect formerly forbidden riches – while denying Americans access to the same objects.

The Vietnamese government’s campaign to repatriate artifacts stems from the recognition that many significant cultural relics were removed from the country (primarily by French colonists and wealthy Vietnamese) during colonial and wartime periods. Artifacts from the Nguyen Dynasty (1802–1945), are much sought after today as they represent nostalgia for Vietnam’s last imperial era, before the country’s wartime sufferings. Enthusiasm for collecting and showcasing history within Vietnam – not current threats to sites or monuments – has led to policies restricting the export of antiquities and appeals for the return of items held abroad, including those in foreign collections and auction houses.

The most prominent example of Vietnamese private collectors going public is the opening of famous Vietnamese collector Do Hung’s private museums in Ho Chi Minh City:

Nguyen Dynasty Artifacts Museum: This museum displays royal antiques, such as clothing, jewelry, and items used by the Nguyen royal family, many of which were sourced through international auctions.

Vietnam’s 54 Ethnic Groups Jewelry Museum: This museum showcases jewelry and artifacts from Vietnam’s diverse ethnic groups, some dating back over 2,500 years.

These well-designed, sophisticated museums also offer educational and interactive experiences, such as the chance for visitors to wear Nguyen Dynasty costumes or explore cultural exhibits from Vietnam’s ethnic minorities. While the government negotiates repatriation abroad, the museums showcase private wealth as well as Vietnamese history.

Government Repatriation Efforts and U.S. Import Restrictions

Vietnam’s government is aggressively pursuing the repatriation of cultural artifacts dating up to 1945, demanding restrictions on U.S. imports of these items as part of its broader efforts to preserve national heritage. However, within Vietnam, a thriving domestic trade in antiques, exemplified by the bustling market in Hải Minh Commune, highlights a contrasting dynamic. This dual approach raises questions about whether ‘preservation’ is really the issue. If Vietnamese in Vietnam can purchase antiques and antiquities, why not American museums, given their importance in guaranteeing access to Vietnamese artifacts for all people, and particularly Vietnamese Americans in the diaspora.

Vietnamese collector Do Hung’s private museum of Nguyen Dynasty artifacts in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Courtesy Nguyen Dynasty Artifacts Museum.

The Vietnamese government has sought international cooperation to recover artifacts that were lost during colonial rule and wars. It should be noted that France, which holds the largest collections of Southeast Asian and Vietnamese artifacts, has never taken steps to return them – even objects originally deemed ‘loans.’

These efforts include urging the United States to impose stricter import restrictions to curb the flow of Vietnamese antiquities into American markets. While these measures seek to protect Vietnam’s cultural legacy, they also create barriers for Vietnamese Americans and collectors abroad, who might have a personal or cultural interest in acquiring artifacts that connect them to their homeland.

Vietnam’s contrasting approaches to artifact access highlight a tension between cultural preservation and inclusivity. Its thriving domestic market also underscores a paradox: the nation’s cultural treasures are readily accessible to those within Vietnam, while the diaspora faces barriers to engaging with their heritage in meaningful ways.

The restrictions effectively prioritize the consolidation of artifacts within Vietnam over access for the global Vietnamese diaspora. Meanwhile, Vietnamese citizens face no such restrictions, enjoying an open and dynamic market where they can buy, sell, and trade historical items freely.

A Thriving Antique Industry at Home

Busy antique market days in Hai Minh Commune Vietnam.

Ironically, within Vietnam, the antique trade flourishes unrestricted. Hải Minh Commune in Hải Hậu District is a prime example, where a vibrant antique market allows collectors to freely trade items from various dynasties, including the Nguyễn Dynasty (1802–1945). Dealers travel domestically and internationally to acquire rare artifacts, contributing to a robust local industry.

Families in Hải Minh have been known as traders in antiques and antiquities for generations. The market is supported by repairers, appraisers, and traders who ensure the continued circulation of antiques within Vietnam. Auctions and exhibitions organized by local associations also bolster the trade.

It has been a lucrative endeavor for the traders. An antique store owner, Sao Huy, told interviewer Ngô Đức Mạnh, “From the junk trade, Hải Minh antiques enthusiasts could buy antiques from the public at the same price as old scraps, the profit can be 10-20 times the capital spent, or even more. That’s why, many antique dealers became billionaires after just a few years in the trade.”[1]

Challenges in the Domestic Market

Despite its vibrancy, Vietnam’s domestic antique market faces challenges, including the prevalence of counterfeits and a lack of professional appraisers. Collectors often rely on self-taught expertise to authenticate items, leaving less experienced buyers vulnerable to fraud.

Vietnam’s newly wealthy individuals, have started paying high prices for local artwork, and some have become targets for unscrupulous traders. International buyers are also at risk, as their belief that they are purchasing genuine pieces is reinforced by institutions that authenticate the artwork.

A photo purportedly showing a painting by the Vietnamese master Ta Ty hanging on a door near four well-known art figures. A photo provided by the family of one of the subjects, which they say is the original, without the painting in question. Top, courtesy of Nghe Thuat Xua; bottom, courtesy of Bui Thanh Phuong.

The Fine Arts Museum in Ho Chi Minh City, for example, played a controversial role in this issue. The museum, where disputed works were displayed as part of the exhibition “Paintings Returned From Europe,” rents its exhibition space to private collectors. This practice lends an air of credibility to the artworks, as they are showcased in Vietnam’s most prominent museum in its largest city.

The exhibition featured 17 paintings owned by Vu Xuan Chung, a Vietnamese art dealer who reportedly paid the museum approximately $1,300 to host the 12-day event in 2017. However, when questions arose about the authenticity of the paintings, the museum quickly determined that none of the 17 pieces had been created by the artists credited in the exhibition. Museum officials issued a public apology and announced plans to hold the paintings for further investigation. Despite this, no investigation was conducted. Instead, the museum quietly returned the paintings.

Even the country’s most important cultural institution, the Museum of Fine Arts in Hanoi, has struggled to determine which of its prized paintings are authentic and which are replicas. During the Vietnam War in the late 1960s, museum officials removed hundreds of artworks from their collection to protect them in case Hanoi was bombed by the United States. They also commissioned replicas to replace the originals on display. Over time, the originals disappeared, the copies were passed off as authentic, and the distinction between the two was lost. When asked whether the museum has since tried to resolve this issue, its director, Nguyen Anh Minh, responded only with a smile.

Further complicating the situation, some relatives of prominent artists have been known to certify copies as originals to sell them at higher prices, exacerbating the confusion in Vietnam’s art market.

Cultural Sites

My Son Sanctuary, courtesy UNESCO.

Vietnam’s World Heritage sites are a driving force behind the growth of tourism in the country.[2] Vietnam, a signatory to the UNESCO World Heritage Convention since 1987, has developed a thriving tourist industry around its UNESCO World Heritage Sites. According to Vietnam’s Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, Tràng An was the most popular World Heritage Site in Vietnam, with more than six million visitors.[3]

- Complex of Huế Monuments (1993) Palaces, temples, and tombs of the Nguyễn Dynasty.

- Hội An (1999) A well-preserved trading port dating back to the 15th century.

- Mỹ Sơn Sanctuary (1999) A cluster of Hindu temples from the 4th to 14th centuries Champa Kingdom.

- Central Sector of the Imperial Citadel of Thăng Long – Hà Nội (2010) The ancient political center of Vietnam, built during the Lý Dynasty.

- Citadel of the Hồ Dynasty (2011) Constructed in the late 14th century, a citadel blending traditional Vietnamese, Southeast Asian and Chinese influences.

- Hạ Long Bay (1994, extended in 2000) Renowned for its stunning limestone karsts and islands, Hạ Long Bay and Hội An attract millions of international visitors annually.

- Phong Nha – Kẻ Bàng National Park (2003, extended in 2015) A karst landscape with some of the world’s largest caves.

- Tràng An Scenic Landscape Complex (2014) Vietnam’s first mixed cultural and natural site, celebrated for its dramatic karst landscapes, ancient temples, and archaeological evidence of human activity dating back thousands of years.

In addition to its eight recognized sites, Vietnam has seven properties on UNESCO’s tentative list, signaling the country’s drive to compete with other tourist venues for the most global recognition.

Looted Artifact Returned to Vietnam

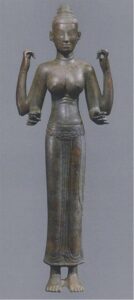

Bronze statue of Goddess Durga, Photo US DOJ.

One major looted artifact has been returned to Vietnam but not from the U.S. A bronze statue of the four-armed Goddess Durga, dating back to the 7th century, was officially returned to Vietnam in a ceremony held in London this week. The artifact, recognized by UNESCO as part of the cultural heritage of the Mỹ Sơn Sanctuary in Quảng Nam Province, had been looted in 2008. The statue has belonged to the late Thai-UK citizen Douglas Latchford who was not alleged to have smuggled it, but to have purchased it with illicitly gotten funds.

The return of the nearly 250-kilogram, two-meter-long statue was the result of the lengthy investigation into Latchford’s activities by U.S. Homeland Security Investigations (HSI), in collaboration with London’s Metropolitan Police. Following Latchford’s passing in 2020, a settlement agreement resulted in the return of over 125 artifacts and $12 million, including the Goddess Durga statue. Latchford’s daughter agreed to repatriate the statue as part of this resolution.

A Side Note

Objects seized from Miller collection returned by FBI to Vietnam.

Among the least noteworthy items that the U.S. has returned to Vietnam, were ten items, including a stone axe and relics from the Dong Son culture, dating from 1000 BCE to the first century CE. The Vietnamese Embassy in the U.S. worked with the FBI to facilitate the return of these objects, deemed cultural treasures in the press.

How did these Vietnamese objects come to the United States? Donald Miller, a 91 year old missionary, was a passionate collector and amateur archaeologist. Alongside his wife, he supported charitable activities and missionary work, building churches in countries like Colombia and Haiti. Over eight decades, the Millers amassed a vast collection of artifacts from over 200 countries, which they proudly displayed in a homemade museum in their Indiana home. The collection included items from World War II, Native American cultures, and various international artifacts, many of which were acquired during their missionary travels and personal excavations.

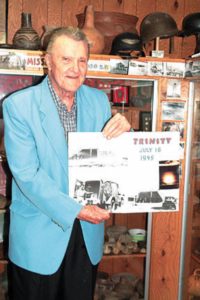

Donald Miller displaying part of his WW2 collection. Photo: Rushville Republican

Miller often hosted tours for local schoolchildren, Scout troops, and community members. His eccentric museum was a celebration of global culture, featuring items such as arrowheads, canoes, baskets, and even a life-sized anaconda in a tunnel connecting the museum’s buildings. Miller used to entertain visitors by playing tunes on his organ while they viewed the collection.

In 2014, at the age of 91, Miller’s museum was raided in a major operation by the FBI, in which more than one hundred heavily armed FBI agents descended on his home and seized much of his collection, alleging that some artifacts had been unlawfully acquired. The operation marked the largest single seizure of cultural property in the FBI’s history, involving more than 7,000 items. While many artifacts were later identified as taken from source countries without supporting paperwork, the Millers maintained that much of their collection was lawfully acquired as curiosities while working as missionaries, or during legitimate archaeological work. Miller died soon after.

Even after the raid, FBI spokesmen did not allege that any law had been violated, but stated that they were carefully assessing the objects to determine if they were unlawfully possessed. In 2014, retired FBI agent Virginia Curry called the raid, “an embarrassing and unnecessary show of force by the FBI.”

[1] Ngô Đức Mạnh, Antiques hunters are flocking to Nam Định City’s Hải Minh Commune hoping to find good deals on the nation’s finest ancient artefacts, March 10, 2024, Viet Nam News, https://vietnamnews.vn/sunday/1651586/the-antique-hunters-of-hai-minh-commune.html

[2] “Giá trị di sản: ‘Át chủ bài’ trong chiến lược phát triển du lịch” [Heritage value: ‘The trump card’ in tourism development strategy] (in Vietnamese). Vietnamese Studies Department of Hanoi National University of Education.

[3] Minh Huyền (9 January 2020). “Số lượng khách du lịch tham quan 8 di sản thế giới tại Việt Nam tăng mạnh” [The number of tourists visiting 8 world heritage sites in Vietnam has increased sharply]. Tổ Quốc (in Vietnamese). Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism.

Central Imperial Citadel of Thang Long - Hanoi, courtesy UNESCO.

Central Imperial Citadel of Thang Long - Hanoi, courtesy UNESCO.