Stonehenge road junction. The busy A303 passes to the left, and the less busy A344 to the right. Photo credit william / Stonehenge road junction / CC BY-SA 2.0

On Salisbury Plain, two very different monuments to human achievement lie side by side: Stonehenge and the A303 highway. Stonehenge, as everyone knows, is an ancient and still mysterious monolith circle, long studied by archaeologists, admired by tourists, and revered by Neo-Pagans and Druidic revivalists. The A303, on the other hand, is an over-burdened stretch of highway connecting major traffic arteries to the north and south. Unfortunately, this highway also runs within a half-mile of Stonehenge itself. The route is heavily trafficked and often the site of long tailbacks caused in part by the tendency of drivers to slow down and stare when passing by Stonehenge, one of the world’s most recognizable historic sites.

For years, Highways England, the government-run company in charge of the country’s highways, has sought to undertake a major reconstruction of the A303, to relieve traffic jams by widening it from two lanes to four and by shifting a two-mile stretch of the highway to an underground tunnel. The problem? This tunnel would run directly through land adjacent to Stonehenge, potentially destroying still-buried ruins or other artifacts and imperiling its status as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

A303 heading west, approaching Stonehenge, 11 October 2009, Photo credit Rob Purvis / A303 heading west, approaching Stonehenge / CC BY-SA 2.0.

Last month, UNESCO issued a warning that, should the highway revision go forward as planned, Stonehenge would be moved to their list of World Heritage Sites in Danger, alongside other imperiled places such as the Florida Everglades, the Bamiyan Valley in Afghanistan and the medieval monuments of Kosovo. UNESCO’s concerns are founded on the projected changes to the site, and the risks those changes would pose to Stonehenge’s historic integrity and that of the surrounding region.

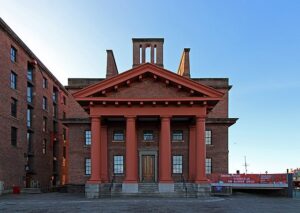

The possibility of Stonehenge’s designation shifting to At Risk ought to be the more troubling in light of UNESCO’s recent decision to remove Liverpool from its list of World Heritage Sites. Liverpool’s World Heritage status rested on its preservation of its historic docks and public buildings, largely built in the nineteenth century when the city throve as a center for maritime trade and manufacture. The redevelopment of the city center, new building on derelict docklands, and the planned construction of a new stadium near the Bramley-Moore Docks, were significant factors in UNESCO’s revoking of the city’s historic status. Local leaders have decried UNESCO’s decision and have long criticized its calls for limiting changes to the city’s historic fabric as unfair restraints on the city’s growth. Resentment of what the Liverpool City Region’s Mayor, Steve Rotheram, called a “binary choice between maintaining heritage status or regenerating left behind communities” is high.

Liverpool Docks, Traffic Office, front elevation, 1 December 2017, Photo credit Rodhullandemu, CCA-SA 4.0 International license

Nonetheless, UNESCO’s revocation of Liverpool’s World Heritage Status is still widely seen as an embarrassing incident for the UK, which prides itself on its wealth of historic sites and monuments. Despite their importance to the nation’s cultural identity, and their role as a draw for the millions of tourists that visit the UK annually, governmental financial support for the upkeep of historic sites is slight. Most UK historic sites rely on their income from visitors, donations, and volunteer workers to survive. The World Heritage Status designation, still enjoyed by thirty-three locations in the UK, can help these sites to attract visitors and to campaign for conservation support from the public.

Campaigners against the highway development are motivated not only by concerns for Stonehenge’s international prestige, but also for the safety of as-yet-undiscovered remnants of Britain’s ancient past, still buried in the soil surrounding the monument. Recent archaeological surveys have found the land around Stonehenge to be rich in architectural remnants, gravesites, and other buried artifacts. The history of Stonehenge itself is still very little understood. Archaeologists and historians continue to debate where the stones came from, when and how they were moved to the site, and what meaning the stone circle held for its makers. The proposed tunnel, or indeed any further construction in the immediate area could destroy materials left behind by Stonehenge’s makers, the only evidence left that could reveal the monument’s true history.

Just days ago, a new obstacle to the highway project arose, one that will likely compel Highways England to significantly revise, if not abandon, its vision for the A303. In November 2020, Grant Shapps, the Transport Secretary, approved a plan for the tunnel, despite popular outcry headed by the citizens’ group Save Stonehenge World Heritage Site (SSWHS). SSWHS brought an immediate legal challenge to the project’s approval, which came before the High Court last week. Mr. Justice Holgate has ruled that Secretary Shapps’ approval of the project was unlawful, due to what the judge determined to be an inadequate effort to assess the risks to each asset at the site and a failure to consider alternatives to the proposed tunnel project required under common law.

The controversy over any highway development near the site has raged for decades but the combined force of the High Court’s ruling and UNESCO’s warning may serve to deter any further pursuit of the project. As the plan’s opponents recently pointed out, there are alternatives to mass construction that might relieve traffic on the road. John Adams, the director of SSWHS, has suggested that Highways England instead “take action to reduce road traffic and eliminate any need to build new and wider roads that threaten the environment as well as our cultural heritage.” Reducing car numbers on England’s highway routes could indeed be a far less destructive means of ameliorating the traffic jam at Stonehenge – and elsewhere. It would also be in line with Downing Street’s climate spokesperson Allegra Stratton’s call for a universal awareness of the “fierce urgency of now” in the UK’s efforts to reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2050.

Tourists around Stonehenge, 13 August 2013, Photo credit Steven Lek, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

Protecting Stonehenge and its surroundings from destruction or disturbance is primarily an act of respect for Britain’s history. It is also a gift to Britain’s future. If the means chosen are appropriate, Stonehenge’s preservation can also contribute to the prevention of further climate change. Protecting the world-famous monument will help to perpetuate the nation’s appeal to international visitors, and ensure that historians can continue to learn new information about the ancient Britons.

It is perhaps most important of all to preserve Stonehenge for its own sake. Like its fellow World Heritage Sites, Stonehenge is unique and irreplaceable, and the least it is owed is that the intrusions of the modern world on its environs be kept to a minimum.

In the 1870s, long before the highway came to Salisbury Plain, the author Henry James visited Stonehenge. Though he noted that the site was already popular with tourists and picnickers, his overwhelming impression was of the monoliths’ solitude and mystique.

“It stands as lonely in history as it does on the great plain, whose many-tinted green waves, as they roll away from it, seem to symbolize the ebb of the long centuries which have left it so portentously unexplained.” …

“There is something in Stonehenge almost reassuring; and if you are disposed to feel that life is rather a superficial matter, and that we soon get to the bottom of things, the immemorial gray pillars may serve to remind you of the enormous background of Time.” [1]

Stonehenge, Wiltshire, photograph with two farm carts, two cart horses and men, circa 1885.

In ordinary years, Stonehenge was visited by nearly a million tourists, surely in search, like James, of contact with a place out of another time, a place with the power to eclipse our fleeting contemporary moment. World Heritage Site or not, bordered by tunnel or highway, Stonehenge will remain an icon of British heritage. How it is treated will likely foretell how all of the UK’s historic sites may fare in the decades to come.

[1] Henry James, Transatlantic Sketches, (Boston: James B. Osgood & Co., 1875): 54-55.

Stonehenge, 31 July 2014, Image Picture Grand Parc Bordeaux, France. CCA 2.0 Generic license.

Stonehenge, 31 July 2014, Image Picture Grand Parc Bordeaux, France. CCA 2.0 Generic license.