Benin bronze plaque. Photo by Mike Peel, Horniman Museum and Gardens, 21 February 2010. CC-BY-SA-4.0.

Introduction

Nick Merriman, who held the position of chief executive and director of content of England’s Horniman Museum and Gardens through 2023, has published an account of the Horniman’s transfer of ownership, title, and copyright of its entire collection of seventy-two Benin objects to Nigeria, “Returning the Benin Bronzes: A Case Study of the Horniman’s restitution,” Palgrave Macmillan; Cham, Switzerland 2024.

The Horniman Museum in Forest Hill, South London, was founded in 1901 to house some 30,000 cultural artifacts, musical instruments and natural history specimens collected by Frederick John Horniman, heir to the Horniman’s Tea Company fortune.

Independent researcher Mike Wells takes a hard look at Merriman’s historical and factual claims regarding the Horniman’s ‘research and consultation process’ and the museum’s arguments supporting return of the bronzes. [1]

A NARROW ETHICAL ARGUMENT

Merriman’s “Returning the Benin Bronzes” begins with a disingenuous glossing over of key issues in the Horniman Museum’s justification for the return of all its Benin objects to Nigeria. Rather than examining international realpolitik and the dramatic increase in cultural nationalism in Third World domestic politics worldwide as causative factor, Merriman credits the 2018 Sarr-Savoy report and the murder of George Floyd in 2020 as the catalysts for a “big, pent-up shift” in museum perspectives on repatriation. It is hard to imagine that a report largely ignored in France and an illegal police action in the USA were key factors overriding museums’ legal trust responsibilities. Similarly, other major issues for ‘colonial’ museums are subsumed in Merriman’s book beneath a selectively fuzzy ‘moral’ imperative. It would have been useful to learn Merriman’s perspective on the political and economic ‘value’ of repatriation in international relations – a factor that may have encouraged massive repatriations from Germany at a time when that country’s oil supply was threatened,[2] or to more fully examine the consequences of the Nigerian President’s 2023 decree turning control over all repatriated objects over to the current hereditary ruler of the Benin kingdom, the Oba Ewuare, instead of to Nigeria’s museum authority.

Ivory armlet, Benin Kingdom, Photo by Mike Peel, Horniman Museum and Gardens, 21 February 2010. CC-BY-SA-4.0.

Instead, the south London museum’s restitution process is described in grinding and self-serving detail. Merriman asserts that the museum had overwhelming support for the return of “stolen objects” among its Lewisham neighbors. However, the Borough of Lewisham is highly diverse: people of Black Caribbean and Black African (3.1% Nigerian) heritage, immigrant Eastern Europeans and a small Indian minority make up 43% of the population.[3] Yet the Horniman’s main public engagement with its Lewisham neighbors turns out to have been an online meeting of 30 self-selected locals, followed by discussion with a panel of just eight visitors.

Much is made of the feelings of schoolchildren and of Lewisham’s Nigerian immigrants of Edo heritage – people from Benin – who felt a fierce sense of injustice on learning that the Benin objects had been ‘stolen.’ Merriman doesn’t examine whether it was also important for them to see the beauty and skill of the artifacts within the context of an unquestionably ugly history of slavery and human sacrifice. There is no indication that the children who weighed in on the return were told anything about this. And what of the larger issue of the museum’s role in presenting both artifacts and historical facts of Benin’s history as it affected the tens of millions of black Brazilians, Caribbeans and Americans who descend from slaves captured and sold by that West African kingdom? The author never mentions the museum’s responsibility to bring this narrative to the fore. While many descendants of enslaved peoples don’t have the comfort of knowing their exact lineage, today’s DNA tests confirm that Benin and Dahomey were the dominant West African slave-hubs from which Caribbean ancestors were sold as chattels.

Benin Copper Alloy Plaque, No. 99.229. Chief Uwangue in center. One of two Portuguese traders holds a manilla copper bracelet, used as currency to purchase slaves and as raw material for the ‘bronzes.’ Horniman Museum and Gardens.

BENIN’S HIDDEN HISTORY

Merriman downplays the regular massed human sacrifice of slaves by the Benin regime, which continued up to Oba Ovonramwen’s overthrow in February 1897, stating that, “the extent and scale has been debated”[4]. He seems not to have read the appalling account of the independent Benin kingdom’s last days by the Oba’s warlord Ojo Ibadan, widely published in 1899.[5] Ibadan had led the massacre of the first British expedition in 1897[6], but he then refused to hand over his mistress for crucifixion – the Chiefs having run out of the other female slaves they used for the purpose – and they seized him instead. He was about to be beheaded at a sacrificial altar when Oba Ovonramwen, his childhood playmate, saved him, though he remained a prisoner until liberated by the British.

Benin plaque depicting a Portuguese soldier with a background of manillas, copper bracelets used in the slave trade. 16-17th C. Photo by Sailko, Grassimuseum – für Völkerkunde, Leipzig, Germany. GNU free documentation license.

The looting of Benin, Merriman claims, “… seems to have been pre-planned with the aim of defraying some of the costs of the military expedition”[7]: but every account of the February 1897 expedition says otherwise. The expedition knew gold was unlikely to be found (unlike at that other slave-trading kingdom, Dahomey) and brass and ivory artifacts were removed more as curious souvenirs rather than for any great market value, according to those who were there. Many more precious wooden objects were lost in an accidental fire which started in the hut of some porters and spread by a strong wind, burnt the Oba’s compounds.[8]

Merriman claims, contrary to every contemporary account, that the British trading expedition of January 1987, whose massacre on its trek to Benin was used to justify the British punitive expedition in February, was “armed”.[9] So emphatically was that first expedition unarmed that the local military band it took along to impress the Oba was made to leave behind weapons of any sort.[10] The trading expedition’s aim was to persuade the Oba to honor his trade treaty, and to desist from selling and murdering slaves: but the expedition had to be intercepted by the Oba’s allies lest outsiders witness “the Ceremony”, an annual mass beheading and disemboweling of slaves in honor of the Oba’s ancestors, that was held over many days that January.

MISSING OBJECTS AND MISSING IDEAS

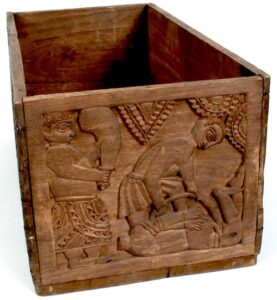

A scorched wooden box in MARKK Museum, Hamburg, one of relatively few wooden pieces to have survived the fire at Benin.

Does a repatriating museum have a responsibility to ensure that objects remain accessible to the public? Merriman downplays the disappearance of items restituted to Nigeria in recent years and shows touching faith in the new Digital Benin database to prevent local museum staff and others from stealing their heritage: “Effectively, any stolen Benin object is now valueless.”[11]. A fair point, if only they were recorded. But museum professionals agree that hundreds of pieces bequeathed by Britain in 1960 and known to have been in the National Museum in Lagos until around 1980 are now unaccounted for and can only have been removed by insiders, whether by theft or sanctioned by officials. (Digital Benin acknowledges that there are only 140 items (many minor) accounted for in the Lagos museum collection. Separately, calls for the state to publish the inventories of its museums at independence in 1960 have been met with silence.)

This vanishing could still happen. In a thus far overlooked crime against scholarship, the Horniman – like Washington’s Smithsonian Museum – handed over not just physical items but the copyright in its own images of pieces it owned until recently[12] : neither the Horniman nor the Smithsonian may permit outsiders to publish the pictures, or even – in the Smithsonian’s case – to look at them without permission from Nigeria, and now, since it transferred ownership and custody, from the Oba. Trying to prove that a restituted bronze relief panel (for example), once secure in a foreign museum, has disappeared from Nigerian custody, will be that much harder – particularly if it doesn’t feature on Digital Benin.

Rubbing of the end panel of the wooden box from Benin in the MARKK Museum, Hamburg. The end panel shows an executioner with his sword standing over a bound and decapitated sacrifice.

Censorship – and worse, voluntary self-censorship – is already taking place: A scorched wooden box from Benin in Hamburg’s MARKK museum (accession no. 1047:05), that is part of the collection already signed over to Nigeria reveals the importance of human sacrifice in Benin’s elite society.[13] Digital Benin’s photos of the box’s carvings include the end panel where an executioner brandishes his sword over a bound, headless corpse – but oddly, not the most striking detail of the lid, executioners displaying a severed head as drummers celebrate. The Oba, who now controls everything to do with repatriated objects, holds the rights to images – and has demonstrated his ‘sensitivity’ to discussion of slavery. Once this incriminating box is in Nigerian hands, would all such images be deleted from the Digital Benin database?

One local consulted by the Horniman during its repatriation discussions daringly suggested that the bronzes might not be properly cared for in Benin but was silenced: the museum’s approach was that its pieces were “stolen goods” and, morally, must be returned. But to whom? The Horniman’s trustees transferred ownership to the National Commission for Museums and Monuments (NCMM), as representing “the Nigerian people”, but everything taken in 1897 had been the Oba’s personal property, and his successors have never relinquished that claim. A Nigerian Presidential Decree ratified the Oba’s ownership and title in March 2023.[14] The Edo people didn’t own or benefit from them then, and nor do they or “the people” now: no pieces returned to Nigeria recently have been shown in any public museum, and that includes the six objects the Horniman handed over in 2022.

Executioner’s sword, Benin, Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. E1902.442.

Merriman references Barnaby Phillips’ “Loot” repeatedly. This former BBC West Africa correspondent’s engrossing book is a model of research, and its author is clear: legally, in 1897 the Benin artefacts were spoils of war – though just two years later, they wouldn’t have been. But the Horniman’s trustees determined that they were “stolen goods” and handing them over was the “moral” thing to do; the museum’s embarrassing collection must be disposed of.

CONCLUDING CONCERNS

Earliest known photograph of Oba’s compound, Benin City, May 1891. Photo by Cyril Punch

First published in Great Benin; its customs, art and horrors (1903) by H. Ling (Henry Ling) Roth (1854-1925), Smithsonian National Museum of African Art. Public domain.

Overall, the book makes clear that the repatriation process was secretive and hurried; there was concern about “significant public attention” if news was “leaked” too early.[15] A new chair of trustees would take office late in 2022 and should not have to take responsibility or rethink the current chair’s decision. The deal had to be sealed. But history is messy; today’s certainties may look otherwise tomorrow. Nigeria may never overcome either its endemic corruption (or its nationwide power cuts) or locate the hundreds of Benin pieces its museums appear to have mislaid since independence. Caring for and displaying restituted artifacts in museums with no electricity won’t be simple, as the Lagos museum has discovered, and a much-touted new museum with modern facilities has still to appear.

Today, fewer Western museums are willing to consider blanket, no-questions-asked restitutions. Restitutions generally ground to a halt after the March 2023 Nigerian government decree that returned artifacts must be handed over to the Oba – though oddly, the decree covers only those restituted now and not pieces of identical provenance which are housed in (or missing from) Nigerian state museums.

University museums in Oxford and Cambridge are no nearer to handing over their collections, and the restitution of 1,130 Benin pieces from German museums has stalled. Over a third belong to the museums of Länder (German states) which have not signed agreements with Nigeria. Only two dozen artefacts from German collections were flown to Abuja in December 2022.

The Royal Palace of the Oba of Benin, Benin City, Nigeria was described as the preferred model for a museum built under the Oba’s auspices. The palace, built by Oba Ewedo (1255AD – 1280AD), is located at the heart of ancient City of Benin. It was rebuilt by Oba Eweka II (1914–1932) after the 1897 war with the British. Author Kelechukwu Ajoku. 13 February 2018. CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

Will history decide today’s ethically-driven museum directors and trustees were wrong to reward the unapologetic descendants of Benin’s slave-traders? Already some argue that the slaves those Obas captured and sold were the real victims. Organizations such as the Restitution Study Group[16] argue that the best tribute to their suffering will be to keep Benin’s artefacts on display in the world’s museums, together with full accounts of that kingdom’s blood-soaked history and of the revolting trade in human beings engaged in by the Obas and their European customers.

Future generations may question today’s rush to restitute, and wonder how we allowed important artifacts to vanish – and what we imagined our museums were for, if not to preserve evidence of former civilizations to be studied, admired, and to continue a more open dialog on human and art history. Only arrogance supposes we, today, have all the answers. Merriman’s 114-page self-exculpation might then be Exhibit A in a public reckoning with today’s museum overseers. Sadly, by Merriman’s account, total visitor numbers, including for hairstyling and musical events, and a metric known as Advertising Value Equivalent took precedence over history, preservation and public access.

Nick Merriman was appointed an Officer of the British Empire (OBE) in January 2024 for services to arts and heritage, and is the new chief executive of English Heritage, where similar questions of ‘decolonization’ will undoubtedly arise. Interviewed by The Times on July 22, 2024 about his new role he insisted, “No way are we trying to distort history. One of the hallmarks of EH is that everything we do is absolutely academically rigorous.”

END

“Returning The Benin Bronzes: A Case Study of the Horniman’s restitution” by Nick Merriman. Palgrave Macmillan; Cham, Switzerland 2024. ISBN 978-3-031-56100-9, ISBN 978-3-031-56101-6 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-56101-6

NOTES

Ezuzu fan from Benin of hide and goatskin, probably 19th C date. 966, nn3171, Photo by Mike Peel, Horniman Museum and Gardens, 21 February 2010. CC-BY-SA-4.0.

[1] Nick Merriman, Returning the Benin Bronzes: A Case Study of the Horniman’s restitution, Palgrave Macmillan; Cham, Switzerland, 2024.

[2] The Benin artifacts may also have been pawns in a massive antiquities-for-gas deal. See Mike Wells, “Looting, Restitution, and Gas: An Update on the Benin Bronzes,” History Reclaimed, March 28, 2023, https://historyreclaimed.co.uk/looting-restitution-and-gas-an-update-on-the-benin-bronzes/

[3] UK Office of National Statistics, “How life has changed in Lewisham,” https://www.ons.gov.uk/visualisations/censusareachanges/E09000023/.

[4] Merriman, Returning the Benin Bronzes, 83.

[5] Mike Wells, “Carry on crucifying – the last days of old Benin,” Daily Sceptic, September 11, 2023, https://dailysceptic.org/2023/09/11/carry-on-crucifying-the-last-days-of-old-benin/

[6] In a possibly unique coincidence, written accounts exist from each side of Ibadan’s hand-to-hand combat with an unarmed English officer, one of the two Englishmen who survived the attack by the Oba’s forces. See Captain Alan Boisragon, The Benin Massacre, Methuen, 1897. Ojo Ibadan’s account of the same incident was published in many UK newspapers in 1899, including the Northampton Mercury, January 13, 1899, p3, Nottinghamshire Guardian, January 14, 1899, p6, Reading Mercury, January 14, 1988, p2, and South Wales Echo, February 14, 1899.

[7] Merriman, Returning the Benin Bronzes, 84.

[8] For a vivid description of the fire and its consequences to the British forces, see Reginald Bacon, Benin: City of Blood, Edward Arnold, London 1897, 106-8.

[9] Merriman, Returning the Benin Bronzes, 30.

[10] Captain Alan Boisragon, The Benin Massacre, Methuen, 1897, 100.

[11] Merriman, Returning the Benin Bronzes, 85.

[12] Id. at 73.

[13] Mike Wells, “Nigerian Prince Proposes to Sell Off Benin Bronzes in Latest Twist to Restitution Farce,” August 11, 2023, Daily Sceptic, https://dailysceptic.org/2023/08/11/nigerian-prince-proposes-to-sell-off-benin-bronzes-in-latest-twist-to-restitution-farce/

[14] Notice No. 25, Order No.1 of 2023, Published in the Federal Republic of Nigeria Official Gazette, Lagos, 28th March 2023, No. 57 Vol 110, pp A245-247.

[15] Merriman, Returning the Benin Bronzes, 59.

[16] Restitution Study Group, https://rsgincorp.org/

Rubbing of the lid of a scorched wooden box in the MARKK Museum, Hamburg, depicting a beheading. One figure holds the severed head, an executioner displays a sword, while drummers celebrate. Illustration from a Neue Zürcher Zeitung article by Prof. Brigitta Hauser-Schäublin, published August 6, 2023.

Rubbing of the lid of a scorched wooden box in the MARKK Museum, Hamburg, depicting a beheading. One figure holds the severed head, an executioner displays a sword, while drummers celebrate. Illustration from a Neue Zürcher Zeitung article by Prof. Brigitta Hauser-Schäublin, published August 6, 2023.