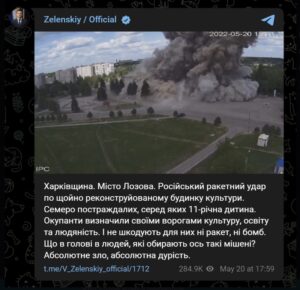

“Kharkiv region. The city of Lozova. Russian missile strike on the newly reconstructed cultural center. Seven victims, including an 11-year-old child… What is in the mind of people who choose such targets? Absolute evil, absolute stupidity.” Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, May 20, 2020.

“The occupiers have identified culture, education and humanity as their enemies.” Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, May 20, 2022, after bombing of the Palace of Culture in Lozova in Kharkiv.[1]

Part One: The Request for import restrictions and the law

On June 4, 2024, the Committee for Cultural Policy (CCP)[2] submitted testimony on a request from the Ukrainian government for a blockade on the import of Ukrainian art and artifacts into the United States. The Request for a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) was made pursuant to the 1983 Convention on Cultural Property Implementation Act (CPIA).[3]

The CCP is entirely in sympathy with the Ukrainian government’s commitment to preserve Ukrainian cultural heritage. This heritage is threatened because of Russia’s brutal invasion and its destruction of museums, monuments, churches, and historic buildings in Ukraine. It is threatened by Russia’s deliberate policy of seizing art for political purposes. Ukrainian heritage is not threatened by looting of artifacts for sale in the United State, which is what the law requires for the U.S. to sign this kind of agreement.

The Committee for Cultural Policy does not oppose a cultural property agreement with Ukraine per se. However, the legal requirements of the CPIA cannot be ignored. In our submissions on all MOUs, we stress the importance of the legal framework that determines whether an agreement is lawful under the CPIA. We urge the Department of State and other U.S. government entities instead to increase their efforts to support civil society, democracy and religious and cultural rights in Ukraine.

Regrettably, the proposed Ukraine MOU is modeled on other egregiously overbroad agreements, covering all objects for more than a million years, that the State Department has signed with other countries over the last decade – creating impossible rules in order to end a lawful circulation of art.

Ukrainian exhibition “Traveling through Odessa,” 28 November 2017, photo Garminder, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

The CPIA is designed to serve a particular purpose: to reduce archaeological looting and theft in art source countries and to preserve the heritage of non-industrial, tribal societies. It is directed toward situations in which countries are suffering serious losses through current looting, even while doing their best to preserve their heritage. If all the conditions in the statute are met – including that the United States is a major market for a country’s looted objects – then import restrictions are appropriate in order to reduce the incentive for pillage in the source nation.

The Ukraine Request is described on the State Department’s Educational and Cultural Affairs website[4] as follows:

“Protection is sought for archaeological material from the Paleolithic Period (approximately 1.4 million years ago) to 1774 CE, including metal (sculpture, jewelry, weapons, coins, vessels, and horse fittings and trappings); ceramic (sculpture, vessels, and seals); stone (sculpture, monuments, vessels, tools, and jewelry); bone, ivory, wood, horn, and other organic material; glass and faience; paintings and mosaics. Ethnological materials for which protection is sought span from the Roman Period (3rd century CE) to 1917 CE and include religious, ritual, and ecclesiastical objects; rare books, manuscripts, and other written documents; architectural elements; objects related to funerary rites and burials, both ritual and secular; paintings; military material; and traditional folk clothing and textiles.”

Miniature Ceramic Dishes – National Museum of Ukrainian Pottery – Opishnya – Ukraine,

Adam Jones from Kelowna, BC, Canada, CCA-SA 2.0 Generic license.

The scope of Ukraine’s Request immediately raises red flags – so many that even aggressively pro-MOU organizations such as the U.S. Committee of the Blue Shield refused to state whether Ukraine’s Request met the criteria for an regular MOU, instead arguing for “emergency restrictions.”** Blue Shield’s recommendation ignored the fact that emergency restrictions are also limited to objects under specific threat and that Ukraine’s 1.4 million year list does not fit U.S. law under emergency rules either; these are supposed to apply to “a newly discovered type of material which is important for the history of mankind and is in jeopardy from pillage, dismantling, dispersal, or fragmentation.” (19 U.S.C. §2603)

The proposition that every type of object made in Ukraine over the last 1.4 million years is subject to pillage is simply impossible. The statute is intended to apply to significant objects.[5] The inclusion of all objects from this vast time-frame contradicts the language in the statute.

Under the CPIA, ‘archaeological’ objects must be least 250 years old, ethnographic objects may be less. The Senate report that explains the statute limits the type of ethnographic object that may be restricted. It states that the CPIA will not apply to objects that are common and duplicative. Further, the types of ethnographic objects that may be restricted are from “nonindustrial societies.” The Senate likened “ethnographic” restricted objects to items such as totem poles or masks from tribal or primitive societies from Africa or South America, and only those items that have particular meaning within those societies.[6] Thus, the statute does not encompass ethnographic material from any advanced European society.

Easter egg (pysanky), a dove of peace, Ukraine, 1970-1980, British Museum (exhibition Ukraine: Culture in crisis), 12 January 2023, photo Ji-Elle, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

The statute presumes that the requesting country does not encourage a domestic trade in objects subject to the “looting” it seeks to curb through an MOU. Logically, the Request should not include coins, ceramics, glass, folk costumes and textiles, and other items that are publicly and lawfully bought and sold within Ukraine. Ukraine cannot reasonably ask the U.S. to impose import restrictions on objects freely traded in Ukraine, because that would not discourage looting.

Under the CPIA, the Request is limited to objects first discovered in Ukraine.[7] Prohibiting the import of coins under the CPIA is always problematic. It is true that a few ancient coins found in Ukraine are rare and valuable. However, the vast majority of coins that are found in Ukraine, whether ancient or Ottoman, circulated in trade by the hundreds of thousands and even millions for centuries, and far beyond the border of Ukraine. They are not exclusively Ukrainian and should not be included. (See below.)

Our concern for statutory conformity is not specific to Ukraine. Rather, it is a general objection to the State Department’s repeated use of a model for MOUs that was developed by a tiny enclave within the State Department that deliberately ignores the criteria set by Congress in order to meet State’s own self-serving diplomatic goals.

It is unquestioned that Ukraine’s museums and cultural institutions have suffered significant losses from deliberate theft by Russian forces. With respect to these losses, the Cultural Property Implementation Act has provisions to halt the entry of any stolen art into the U.S. without the need for an MOU. They are already covered under the CPIA statute; all stolen items regardless of origin may be seized.[8]

Part Two: The crimes against heritage in Ukraine

“I would like to underscore that Ukraine is not just a neighboring country to us, it is an inherent part of our own history, culture, spiritual space… Ukraine has never had stable traditions of their own statehood.”

Speech by Russian President Vladimir Putin 21 February, 2022, after a UN Security Council meeting and just before the invasion of Ukraine.[9]

Destruction of villages on the outskirts of Sloviansk, July 19, 2022, State Emergency Service of Ukraine, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

Putin’s statement is nonsense, of course. Ukraine is a distinct and independent European country with its own distinctive heritage. The government of Russia and its armed forces and mercenary armies are the culprits in the looting and theft of Ukraine’s cultural property. They are responsible for its damage and destruction. Looted goods are being welcomed to Russia’s museums and claimed as that country’s own, not being smuggled to the U.S. The criminal plundering of Ukraine is part of a deliberate campaign to reframe Ukrainian heritage as Russian and to deny Ukraine’s historical identity.

The CPIA is not designed to deal with situations like that of Ukraine. There needs to be clear evidence that a U.S. MOU with Ukraine will have a positive effect for the preservation of Ukraine’s cultural heritage before any MOU is approved. Depending upon its scope, an MOU could also pose harm to the interests of Ukrainian refugees and their families and to immigrant communities in the United States by blocking entry to their religious and personal property.

As we will describe below, the looted art and artifacts seized from Ukraine and illegally transported to Russian museums are not taken for ‘safe-keeping’ but in order to be ‘Russified’. Ukrainian history is being deliberately rewritten to serve Russian political aims. As far as Russia is concerned there is no Ukrainian history outside of its identity as ‘Rus.’

Blanket U.S. import restrictions are not able to address Ukraine’s fundamental problem, which is the wartime destruction of its cultural sites and the forcible removal of its cultural heritage by Russian authorities. A purely symbolic, overly comprehensive MOU would not help Ukraine and could harm the interests of refugees and displaced Ukrainians. The only actions we can take under the statute must be limited to what Congress intended and based upon actual evidence of looted objects entering the United States.

Piece of a house in Black Sea in Odesa region of Ukraine after the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam. 10 June 2023, Photo State Border Guard Service of Ukraine, credit Dpsu.gov.ua, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

In any case, a U.S. market for illicitly obtained Ukrainian art and artifacts has not been established. Of the reported 85,000 missing artworks and artifacts from Ukrainian collections, only 14 objects have been located coming into the United States and these have been returned by the FBI.[10] Americans will not knowingly acquire such tainted stolen goods. An educational campaign is the most positive and effective means to focus public and Congressional attention on the ongoing destruction. We encourage the State Department to continue its funding and cooperative work in this area with Ukrainian heritage authorities to preserve and restore Ukraine’s national patrimony.

Finally, being mindful of the positive role that both private and public exchange and circulation of art plays in today’s global culture, we urge the CPAC to consider alternative measures available to preserve Ukrainian heritage, as the statute requires.

The United States is a country of laws – and CPAC’s actions must comply with the law, or they will be worse than meaningless. U.S. import restrictions must still fit within the criteria of the Convention on Cultural Property Implementation Act.

This is an ongoing war.

Let’s be clear. In a war there will always be people who take advantage of its chaos and gather unprotected items as spoils. There have been a few well-publicized instances of greedy or panicked Ukrainian officials who have taken advantage of their position to steal items from Ukrainian museums and institutions. They have been caught – and future robbers will continue to be caught – because the Ukrainian government is committed to the rule of law and because there are thousands of Ukrainians risking their lives to stay in Ukraine and save their country’s heritage from such robbers and thieves. Ukrainians are working day and night to identify and protect Ukrainian heritage.

Relevant international laws.

Yakovlivka village in Kharkiv Raion of Ukraine after air attack during Russian invasion of Ukraine. 3 March 2022, State Emergency Service of Ukraine, Dsns.gov.ua, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

The brutal invasion of Ukraine, an independent and sovereign country in Europe, with devastating loss of human lives, the destruction of its historic cities, and damage to invaluable cultural and natural heritage, are ills solely due to the government of Russia. Russia’s actions are a violation of Article 53 of the Additional Protocol I of 1977 to the Geneva Convention of 1949, which states that “historic monuments, works of art or places of worship which constitute the cultural or spiritual heritage of peoples” must not be used in support of military efforts or made the objects of acts of hostility.[11]

The 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict[12] requires its signatories (which include both Ukraine and Russia) to respect the “movable or immovable property of great importance to the cultural heritage of every people,” as well as institutions such as museums or libraries housing cultural heritage objects. Signatory nations must prohibit, prevent, and put an end to theft, pillage and misappropriation of cultural property. While cultural properties can become legitimate military objectives under a waiver of “imperative military necessity,” this is only permissible of if the cultural property has been employed for a military objective, for instance, by being used by the other party as a shield for their own attack.

Ivankiv Historical and Local History Museum (Kyiv region) after Russian shelling on 25 February 2022 Author Ministry of Culture and Information Policy of Ukraine, CCA 4.0 license.

Under the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights,[13] Russia and Ukraine must ensure “the right to access and enjoy cultural heritage” with regard to populations both under their jurisdiction and under their effective control, for example, inside occupied Ukraine.

Unfortunately, although Russian has signed the 1954 Hague Convention, the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights and of course the 1972 UNESCO World Heritage Convention,[14] it has violated them in the most egregious way imaginable in its invasion of Ukraine. These conventions lack enforcement mechanisms, and any response is contingent on the willingness of international bodies to implement sanctions or other punishment.

Attacks on cultural heritage can amount to war crimes and can be prosecuted before the International Criminal Court.[15] Ukraine is working diligently to document Russia’s destruction specifically for that purpose. The widespread and coordinated destruction of Ukrainian cultural and civic life has led to allegations of potential genocide by the New Lines Institute for Strategy and Policy and the Raoul Wallenberg Centre for Human Rights.

Russia’s military is destroying cultural heritage and civilian infrastructure in violation of its own military rules.

The official “Manual on International Humanitarian Law for the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation” shows that the Russian military is violating not only international law, but also Russian law in its destruction of cultural heritage in Ukraine. The 2001 manual states:

“Prohibited methods of warfare include “killing or wounding civilians … taking of hostages… terrorizing the civilian population; using starvation of civilians to achieve military objectives, the destruction, removal or reduction to uselessness of objects indispensable to their survival … destroying cultural property, historic monuments, places of worship and other objects of cultural or spiritual heritage of peoples …; destroying or capturing enemy property, unless required by military necessity; ordering to pillage a town or place.”[16]

Documenting loss of heritage for reconstruction and making the case for Russia’s war crimes.

Khanenko Museum in Kyiv during the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. The paintings are taken off the walls and moved to shelters. Photo Kyiv City State Administration, Oleksiі Samsonov, 13 April 2022, CCA 4.0 International.

Ukrainian government websites encourage reporting of heritage crimes.[17] The government had documented 902 damaged cultural sites by February 2024, including antique buildings, theaters, monuments, churches, and archaeological sites, showcasing Russia’s violations of the 1954 Hague Convention.[18] Religious sites have been particularly targeted, causing significant distress among Ukrainians, especially older and rural populations.

International organizations are also actively documenting the damage. The International Alliance for the Protection of Heritage in Conflict Areas (ALIPH) and the Heritage Rescue Emergency Initiative (HERI) are tracking data on site damage, while the Smithsonian Cultural Rescue Initiative and Cultural Heritage Monitoring Lab (CHML) have used satellite imagery to monitor 26,000 cultural heritage sites in Ukraine.

Efforts are also being made to prevent the cross-border transportation of stolen objects. Organizations like the International Council of Museums (ICOM), the World Customs Organization, Interpol, and UNESCO are collaborating to stop the illegal movement of Ukrainian artworks. In May 2022, British authorities intercepted a shipment of early medieval jewelry bound for the UK, and in June, Ukrainian authorities seized over 6,000 antiquities in Kyiv that were in the hands of a now disgraced Ukrainian government official and tied up in a money laundering scheme run by Russian-backed separatists in Donetsk.[19]

Seized Russian property should be dedicated to reparations for war crimes against heritage and U.S. authorities should work with organizations documenting heritage losses to attempt to establish Ukrainian title to items in Russia.

Russia’s war against Ukrainian culture.

Maria Prymachenko, Ukrainian postage stamp issued 1999. Ukrposhta, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

One of Russia’s initial actions in its invasion of Ukraine was the deliberate burning of the Ivankiv Museum, which housed works by renowned Ukrainian folk artist Maria Oksentiyivna Prymachenko. Prymachenko, who passed away in 1997, remains a potent symbol of Ukrainian identity and cultural heritage. Her work was greatly valued by the people of Ivankiv, evidenced by a local man’s bravery when Russia struck, risking his own life to rescue ten of her cherished artworks from the flames.

The destruction of the museum was a targeted attack on Ukrainian cultural identity. Ukrainian folk art, particularly in the early 20th century, played a significant role in expressing national independence and cultural distinction from Russia. The torching of the museum conveyed Russia’s denial of Ukrainian identity and independence.

This act was part of a broader, long-standing Russian strategy to undermine Ukrainian civic life and cultural identity. Since the 2022 invasion, Russia has specifically targeted local expressions of civic life such as libraries, schools, hospitals, marketplaces, city centers, monuments, and museums.

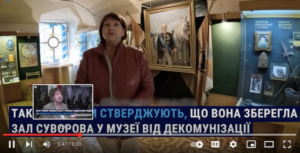

Ukrainian museum curator kidnapped to find art.

Galina Kucher, a curator at the Melitopol Museum of Local History. She was kidnapped twice by Russian forces trying to find Scythian treasures. Photo via Facebook.

On April 30, 2022, Melitopol’s mayor reported that Russian forces had seized the Melitopol Museum of Local History’s most valuable holdings, including its collection of Scythian gold. Ukrainian museums are known for their exceptional examples of Scythian gold, and Melitopol’s collection was particularly notable.

In March, Russian troops kidnapped the museum director, Leila Ibrahimova, interrogated her for hours, and then released her. She fled Melitopol, but later learned from curator Galina Kucher that Russian soldiers, together with a new museum director appointed by the Russian military, had found where museum staff had hidden its most precious items. The Russian forces had spent weeks searching for the museum’s secret storage place and eventually took several hundred exceptional golden objects, including a Hunnish period gold tiara, and about 1,700 other artifacts. This theft was filmed by a Russian crew. Kucher, a respected academic, was kidnapped herself after the theft was reported in Western media.[20]

In Mariupol, a city heavily affected by the war, over 2,000 exhibits were taken by Russian forces and transferred to Donetsk. The Mariupol local history museum was bombed and nearly destroyed. The Arkhip Kuindzhi Art Museum, dedicated to a Ukrainian Realist painter, was destroyed in an airstrike on March 20. On the same day, Russia bombed Mariupol’s G12 art school, where 400 civilians were sheltering. Days earlier, the Donetsk Regional Theatre of Drama, sheltering about 1300 people, was shelled, with only about 130 survivors.

Heritage workers face similar dangers to civil activists and journalists due to their efforts to preserve Ukrainian cultural identity. Ukraine’s cultural minister, Oleksandr Tkachenko, reported that Russian soldiers have taken items from nearly 40 Ukrainian museums, calling it a war crime.

Kherson museum’s Russian-installed new director, Tatiana Bratcheck, is featured in propaganda videos graciously welcoming Russian “guests” to the museum.

In Kherson, new directors suspected of collaborating with Russians were installed in museums during its Russian occupation. The Kherson Regional Museum and the Oleksiy Shovkunenko Kherson Art Museum, which house significant collections including icons, Ukrainian paintings, and European artworks, were under Russian control for months. Acting Minister of Culture and Information Policy Rostyslav Karandieiev reported in February 2024:

“When we liberated Kherson and visited the museum institutions, including the Kherson Art Museum, we saw that out of 13,000 exhibits, only 3 remained. What is happening in the territories that, regretfully, have been occupied for 10 years, we can only guess. The status of nearly 85,000 cultural values is unknown.”[21]

Ukrainian cultural authorities have emphasized the critical role of art in maintaining Ukrainian identity. Taras Voznyak, director of the Lviv National Art Gallery, said that “With each invasion, some loss of culture is inevitable… Putin knows that without art, without our history, Ukraine will have a weaker identity. That is the whole point of his war — to erase us and assimilate us into his population of cryptofascist zombies.”[22]

Russian museum directors support Putin’s war.

Vladimir Putin with Director General of the State Hermitage Museum Mikhail Piotrovsky.

Many prominent figures in the Russian contemporary art scene have publicly opposed the invasion of Ukraine. In March 2022, Vladimir Opredelenov, deputy director of the State Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, resigned due to disagreements with colleagues over the invasion. Francesco Manacorda, artistic director of the VAC Foundation, and Simon Rees, artistic director of the Cosmoscow art fair, also resigned in protest. Rees moved to Vienna to aid Ukrainian refugees.[23]

Conversely, some directors of Russia’s major museums have supported Putin and the invasion. Hermitage director Mikhail Piotrovsky criticized the suspension of relations with Russia by Western museums, calling it a continuation of colonialism and aligning himself with Russian territorial ambitions.[24]

Some Russian cultural leaders have faced sanctions from Europe and other countries. Aleksandr Shkolnik, director of Moscow’s Museum of the Great Patriotic War, was sanctioned by Australia and the UK for promoting the Russian government’s false narrative of “de-Nazification” in Ukraine. Shkolnik expressed pride in the sanctions, maintaining that ‘Ukrainian neo-Nazis’ would eventually be condemned.[25]

Russia’s destruction of Stone Babas and archaeological sites.

Post by Oksana Semenik showing destruction of ancient stone babas, ancient relics of Turkic civilization in Ukraine.

“Stone babas” are roughly made but powerful stone figures dating from the 6th century BCE to the 13th century CE. Ukraine reports that many have been removed from or destroyed in situ around the country by Russian forces. Similar figures from Scythian to Turkic cultures are found in a variety of forms from Eastern Europe and across the steppe lands as far as Mongolia. The Stone Babas appear to be victims of both deliberate destruction in war and Russian attempts to rewrite history by eliminating or appropriating archaeological evidence.

Russia’s political claims to Ukrainian art and history were evident well before the 2022 invasion. A major controversy following Russia’s annexation of Crimea was its demand for control over objects loaned from Ukrainian museums in Crimea before the annexation. Shortly after the invasion and a staged referendum, Russian authorities initiated rapid archaeological digs, particularly near construction sites for a highway and bridge linking Sevastopol with Russian territory via the Kerch Strait. Russian media reported the excavation of one million artifacts, while the Ukrainian Ministry for the Reintegration of Temporarily Occupied Territories identified 29 illegal excavations by July 2021.[26]

Cuman statues from the Kharkiv Oblast, Ukraine, 12th century, Neues Museum, Berlin, photo Ethan Doyle White, CCA-SA 3.0 Unported license.

A UNESCO report from September 2021 stated that Russia had appropriated 4,095 Ukrainian cultural properties on the Crimean Peninsula, including national and local monuments.[27] It described the appropriation as a violation of international law and part of a broader strategy to reinforce Russian historical, cultural, and religious dominance over Crimea’s past, present, and future. The report highlighted efforts to erase Crimean Tatar history, such as the destruction of Muslim burial grounds. The Crimean Tatars, a Turkic Muslim population who were the majority in Crimea from the 10th to the 19th centuries, faced mass deportation under Stalin, resulting in the death of 20-45% of their total population. Their right to return to Crimea was only partially acknowledged by Soviet policy in 1989. Russia still denies that they are indigenous Crimean peoples with title to the land, although they lived there for 1000 years. Even today, the Tatars make up only about 15% of Crimean people.[28]

Monuments to the Wagner Group mercenaries installed by Russia.

A month before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Damian Koropeckyj, a Senior Analyst at the Cultural Heritage Monitoring Lab (CHML), published an analysis in Small Wars Journal identifying two key narratives in Russian Information Operations (IO): portraying Ukrainians as neo-Nazis and framing the war in the Donbas as a continuation of World War II, and depicting southern and eastern Ukraine, as well as Crimea, as historically Russian territories.

Wagner Memorial in Bangui, Central African Republic, Feb. 23, 2022, Voice of America.

Koropeckyj illustrated how Russia uses tangible cultural heritage to support these narratives, focusing on monument construction in Crimea and separatist-held areas of eastern Ukraine. He highlighted examples such as the 2015 installation of a statue of Stalin, Roosevelt, and Churchill at Livadia Palace, despite prior protests by Crimean Tatars, and a monument to Tsar Alexander II installed in 2017 by President Putin. He identified 91 recent monuments in Crimea and eastern Ukraine, many of which emphasize the defense of the homeland during WWII or valorize Russian mercenary activities.

The valorization of Russian mercenary activities is seen in the construction of a prefabricated monument to “Russian Volunteers” set up in Luhansk, similar to one in the Central African Republic and at a Wagner Group base outside of Palmyra, Syria.[29]

In a presentation for the American Bar Association’s Art & Cultural Heritage Law Committee, Dr. Brian Daniels of the Penn Cultural Heritage Center at the University of Pennsylvania noted that the recent building of pro-Russian monuments in other former Soviet and Baltic countries might signal future Russian irredentist claims.[30] He also pointed out that the destruction of cultural heritage in other nations follows similar patterns, including targeting sites associated with independence movements, destroying civic infrastructure such as bakeries, libraries, and churches, and stealing important artworks for propaganda purposes.

Dutch Court: Scythian gold from Crimea should go to Ukraine.

Gold pectoral with griffins attacking horses at lower register, shepherds milking ewes, horses, and men stretching a sheepskin in upper register. Kiev Museum of Ukrainian Art, Kiev, Ukraine.

In February 2014, the Allard Pierson Museum in Amsterdam opened an exhibition showcasing ancient artifacts from the Black Sea region, on loan from four museums in Crimea and one in Kiev. The Russian invasion of Crimea in late February 2014 complicated the planned return of these artifacts, leading to claims from both Ukraine and Russia. Ukraine argued that the artifacts belonged to its cultural heritage, as the loans were made when Crimea was under Ukrainian control. Russia claimed ownership based on its annexation of Crimea and cultural affinity with the artifacts.

The loan agreements described the items as part of the “Museum Fund of Ukraine,” underscoring their Ukrainian ownership. Despite this, some Crimean museum officials, like Andrey Malgin, argued the artifacts were inherently Crimean and should be returned to the lending museums, not to either government.[31]

The legal dispute over the artifacts’ return involved teams from Russia, Ukraine, and the University of Amsterdam. Amid strained Russian-Dutch relations, the Dutch District Court ruled in December 2016 that the artifacts should be returned to Ukraine, citing Ukraine’s legal ownership under its museum laws and the 1970 UNESCO Convention. The court did not decide on the ultimate ownership, leaving that to Ukrainian courts.

Following an appeal by Crimean museums, the Dutch appellate court upheld the decision in October 2021, affirming Ukraine’s control over the artifacts. The Dutch Supreme Court finalized this ruling on June 9, 2023, confirming that over 1000 gold objects should be returned to Ukraine, not to the Crimean museums. This decision reflects the ongoing international non-recognition of Russia’s annexation of Crimea.[32]

ICOM issues ‘Red List’ for Ukraine.

“Unfortunately, the rules developed and adopted by all ICOM members no longer work.” Letter from ICOM Ukraine to the Prague general meeting, August 2022.[33]

Gold torque with griffins, shepherds. Returned to the Kiev Museum of Ukrainian Art, Kiev, Ukraine. Photo Allard Pierson Museum.

In September 2022, ICOM, the International Council on Museums, announced the publication of a Ukraine Emergency Red List of Cultural Objects at Risk. The purpose of a Red List would be to identify typical Ukrainian materials that might be looted or stolen, using legal artifacts from museums as examples. The Red List is intended to alert law enforcement and the public of the types of objects considered most at risk. Red Lists provide extremely basic information and many objects shown are not exclusive to the countries for which Red Lists exist. Although ICOM’s announcement stated that there was ‘evidence’ of stolen objects flowing back to Europe, such data is lacking. The problem is Russian seizures and destruction, not an illegal art market.

UNESCO: part of the problem as well as part of the solution.

The protection of cultural heritage no longer holds a special, enlightened position in international relations. UNESCO, which excels in data collection, listing, tracking, and reporting on heritage destruction, has historically avoided criticizing state actors for cultural destruction within their own borders.

Although UNESCO’s founding principles emphasize that heritage is a shared responsibility of all people, not just national governments, the organization has often prioritized national ownership and nationalist claims. This has led to neglecting the vision of heritage as a human right, particularly for minority communities.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine tested UNESCO’s effectiveness. While UNESCO and cultural institutions worldwide expressed concern for Ukraine’s museums and heritage sites, UNESCO’s actions, such as marking key monuments with the emblem of the 1954 Hague Convention, had zero impact. Within just a few months of Russia’s invasion in February 2022, nearly 100 significant cultural sites in Ukraine had already been destroyed and the total of destroyed sites is now about 900.

Import restrictions should be modified to exclude cultural objects such as coins in legal trade within Ukraine.

Archaeological finds in National Museum of the History of Ukraine, December 3, 2016, photo Star61, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

CPAC should ensure that import restrictions on coins are strictly limited to those “first discovered within, and subject to export control by” Ukraine, as stipulated in CPIA, U.S.C. § 2601. Ukraine only began issuing its own coinage after gaining independence in 1991, and coins from Eastern and Northern Europe, Russia, and Ukraine are substantially similar, making it difficult to determine exclusive Ukrainian origins. Ancient Greek coins from the Russian-occupied Crimean Peninsula have not been under Ukrainian export control for a decade.

The Ukrainian government allows sales of ancient coins domestically. It is illogical to ban Americans from importing coins sold openly in Ukraine. CPAC should recommend that Ukraine regulate metal detectors as a “self-help” measure and require export certificates to be issued for common coins. Enforcement reforms should protect the legitimate trade in Ukrainian coins in the EU, Switzerland, and the UK.

Allowing the sale of metal detectors without recognizing their use for treasure hunting is unrealistic, as highlighted by Mateusz Bogucki and Kyrylo Myzgin in their analysis of the confusing and contradictory Ukrainian laws on finds and metal detecting.[34]

Archaeological finds in National Museum of the History of Ukraine, December 3, 2016, photo Star61, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

Coins must meet the CPIA’s “cultural significance” criteria for restrictions. The abundance of historical coins argues against them being considered “culturally significant.” The exception may be coins of Kievan Rus, significant to Ukraine’s national identity.

By law, CPAC must consider “self-help” measures and “less drastic remedies” before imposing restrictions on American collectors and small numismatic businesses. These remedies include regulating metal detectors, creating a workable export system, and ensuring that import restrictions are not embargoes. As we have stated many times before, CCP recommends that countries adopt a system similar to the UK’s Portable Antiquities Scheme, which rewards those who discover antiquities and report them so that archaeologists can properly excavate and researchers document them, and afterwards allows permitted sales of extraneous objects.

See in this issue: A Closer Look at the Portable Antiquities Scheme

Given the active market for ancient and early modern coins in Ukraine, facilitating American participation aligns with the international interest in cultural property exchange. While there are obvious reason why immediately implementing such an advanced system is not possible for Ukraine today, allowing legal, supervised and permitted circulation of art and artifacts has the potential to support heritage preservation in Ukraine in the future.

Conclusion

- The Committee for Cultural Policy agrees that the cultural heritage of Ukrainian is in jeopardy, not from domestic looting for profit but because of Russia’s war.

- CCP appreciates that Ukraine has taken extraordinary measures to try to protect its cultural patrimony, to document it and to make that information accessible throughout the world on the Internet.

- CCP is confident of Ukraine’s future willingness to work with U.S. museums to ensure that rare and important Ukrainian art is accessible through travelling exhibitions for the enjoyment and appreciation of the American public. We are also confident, given Kiev’s past history, that U.S. scholars will be welcomed in the future Ukraine for scientific, cultural and educational purposes.

Ukrainian girl by Nikolay Rachkov Ephimovich (1825—1895) 2nd half 19 c., Chernigov Museum, public domain.

However, we believe that the proposed MOU is incompatible with the statutory requirements of the CPIA. If any MOU is recommended, it should be limited solely to art and artifacts for which there is actual evidence of unlawful export to an illicit market in the United States. We have not seen evidence that such an illicit market exists.

Further, the Committee for Cultural Policy recommends that CPAC seriously consider whether placing import restrictions on Ukrainian art and artifacts would be of any practical assistance whatsoever in halting the serious losses to Ukrainian heritage caused by Russia’s invasion.

The CCP supports all measures to assist in the protection of Ukrainian heritage, but a U.S.-Ukrainian MOU would be completely useless in halting Russia’s seizures of art and artifacts or the destruction of Ukrainian heritage by Russian forces.

CPAC and the Department of State should focus instead on providing alternative forms of assistance, particularly in documentation and preservation activities within Ukraine, as the best and most positive way of helping the people and government of Ukraine.

** The U.S. Committee of the Blue Shield’s commentary is available under https://www.regulations.gov/comment/DOS-2024-0015-0051

Sunflowers at the Museum of Folk Architecture and Ethnography in Pyrohiv, Kyiv, Ukraine, 22 March 2019, photo Maksym Kozlenko, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

[1] Zelensky slams Russian strikes on Ukraine culture center, Straits Times, May 21, 2022, https://www.straitstimes.com/world/europe/zelenksy-slams-russian-strikes-on-ukraine-culture-centre

[2] The Committee for Cultural Policy (CCP)[2] is an educational and policy research organization that supports the preservation and public appreciation of art of ancient and indigenous cultures. We deplore the destruction of archaeological sites and monuments and encourage policies enabling safe harbor in international museums for at-risk objects from countries in crisis. CCP supports policies that enable the lawful collection, exhibition, and global circulation of artworks and preserve artifacts and archaeological sites through funding for site protection. We defend uncensored academic research and urge funding for museum development around the world. We believe that communication through artistic exchange is beneficial for international understanding and that the protection and preservation of art from all cultures is the responsibility and duty of all humankind. The Committee for Cultural Policy, POB 4881, Santa Fe, NM 87502. www.culturalpropertynews.org, info@culturalpropertynews.org.

[3] The Convention on Cultural Property Implementation Act, 19 U.S.C. §§ 2601, et seq.

[4] Cultural Property Advisory Committee Meeting, June 4-6, 2024, https://eca.state.gov/highlight/cultural-property-advisory-committee-meeting-june-4-6-2024

[5] 19 U.S.C. § 2601(2)(i)(I)

[6] ““Ethnological material” includes any object that is the product of a tribal or similar society, and is important to the cultural heritage of a people because of its distinctive characteristics, its comparative rarity, or its contribution to the knowledge of their origins, development or history. While these materials do not lend themselves to arbitrary age thresholds, the committee intends this definition to encompass only what is sometimes termed “primitive” or “tribal” art, such as masks, idols, or totem poles, produced by tribal societies in Africa and South America…

The committee does not intend the definition of ethnological materials under this title to apply to trinkets and other objects that are common or repetitive or essentially alike in material, design, color, or other outstanding characteristics with other objects of the same type, or which have relatively little value for understanding the origins or history of a particular people or society.” Senate Report 97-564, 6

U.S. Senate Report, 97-564, Implementing Legislation for the Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export, and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property, 7.

[7] 19 U.S.C. § 2601(2)(C)

[8] 19 U.S.C. § 2601

[9] Russian President Putin Statement on Ukraine, February 21, 2022, CSPAN, https://www.c-span.org/video/?518097-2/russian-president-putin-recognizes-independence-donetsk-luhansk-ukraines-donbas-region

[10] Government of Ukraine, ‘Ukraine and USA strategize new way to cooperate in investigating Russian crimes against cultural heritage,’ 19 February 2024, https://www.kmu.gov.ua/en/news/ssha-ta-ukraina-rozrobliat-stratehiiu-spivpratsi-shchodo-rozsliduvannia-zlochyniv-rf-proty-kulturnoi-spadshchyny

[11] Kristen Hausler and Berenika Drazewska, How does international law protect Ukrainian heritage?, British Institute of International and Comparative Law, https://www.biicl.org/blog/37/how-does-international-law-protect-ukrainian-cultural-heritage-in-war-is-it-protected-differently-than-other-civilian-objects.

[12] UNESCO, 1954 Convention Cultural Heritage and Armed Conflicts, https://www.unesco.org/en/heritage-armed-conflicts/convention-and-protocols/1954-convention

[13] United Nations, International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-economic-social-and-cultural-rights

[14] UNESCO, 1972 Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage, https://whc.unesco.org/en/conventiontext/

[15] Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, Art. 8(2)(b)(ix).

[16] Evan Wallach, Russian Leaders Know They’re Committing War Crimes. Their Laws of War Manual Says So, Lawfare Institute, April 25, 2022https://www.lawfareblog.com/russian-leaders-know-theyre-committing-war-crimes-their-laws-war-manual-says-so

[17] https://www.kmu.gov.ua/en/news/ministry-culture-and-information-policy-encourages-reporting-crimes-against-cultural-heritage-committed-occupants-ukrainian-territory

[18] Government of Ukraine, Due to Russian Aggression in Ukraine, 902 cultural heritage sites have been affected, https://www.kmu.gov.ua/en/news/cherez-rosiisku-ahresiiu-v-ukraini-postrazhdaly-902-pamiatky-kulturnoi-spadshchyny

[19] Tim Brinkhoff, ‘How and why stolen Ukrainian art ends up on the black market,’ Big Think, October 13, 2023, https://bigthink.com/high-culture/black-market-art-ukraine/

[20] ‘They put me in a car, put a black bag on my head – Leila Ibrahimova about her detention’, https://ctrcenter.org/en/7676-mene-posadili-v-avto-nadyagli-na-golovu-chornij-mishok-lyejla-ibragimova-pro-svoye-zatrimannya

[21] Government of Ukraine, Ukraine and USA strategize new way to cooperate in investigating Russian crimes against cultural heritage, 19 February 2024, https://www.kmu.gov.ua/en/news/ssha-ta-ukraina-rozrobliat-stratehiiu-spivpratsi-shchodo-rozsliduvannia-zlochyniv-rf-proty-kulturnoi-spadshchyny

[22] Max Bearak and Isabelle Khurshudyan, ‘All art must go underground’: Ukraine scrambles to shield its cultural heritage, Washington Post, 14 March 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/03/14/ukraine-odessa-russia-war/

[23] Kate Fitz Gibbon, Russia’s War Against Ukrainian Culture, Cultural Property News, August 2, 2022,https://culturalpropertynews.org/russias-war-against-ukrainian-culture/

[24] Id.

[25] Id.

[26] Id.

[27] Sophia Kishkovsky, UNESCO report reveals extent of Russian threat to Crimean heritage, 16 September 2021, The Art Newspaper, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2021/09/16/unesco-report-reveals-extent-of-russian-threat-to-crimean-heritage

[28] Crimean Tatars, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crimean_Tatars

[29] Damian Koropeckyj, Cultural Heritage in Ukraine: a Gap in Russian IO Monitoring, Small Wars Journal, January 21, 2022, https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/cultural-heritage-ukraine-gap-russian-io-monitoring

[30] Dr. Brian Daniels, director of research and programs at the Penn Cultural Heritage Center at the University of Pennsylvania, speaking on the current cultural heritage situation in Ukraine before the American Bar Association’s Art & Cultural Heritage Law Committee on May 12, 2022

[31] Kate Fitz Gibbon, ‘Dutch Court: Scythian Gold from Crimea should go to Ukraine,’ Cultural Property News, October 31, 2021, https://culturalpropertynews.org/dutch-court-scythian-gold-from-crimea-should-return-to-ukraine/

[32] CCP Staff, ‘Law Note: Netherlands Court Rules Scythian Gold must go to Ukraine, Cultural Property News, June 17, 2023, https://culturalpropertynews.org/law-note-netherlands-court-rules-crimean-gold-must-go-to-ukraine/.

[33] Kate Fitz Gibbon, ‘ICOM Condemns Russia’s Destruction of Ukrainian Heritage,’ Cultural Property News, September 27, 2022, https://culturalpropertynews.org/icom-condemns-russias-destruction-of-ukrainian-heritage/

[34] Kyrylo Myzgin, The Law and Practice Regarding Coin Finds: Poland and Ukraine, Compte Rendu 68/2021 17, 21-24 (International Numismatic Council 2021).

St. George's Church in Drohobych, 23 April 2017, photo Moahim, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

St. George's Church in Drohobych, 23 April 2017, photo Moahim, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.