Benin bronze at the Horniman Museum depicting a warrior and two Portuguese traders holding Manilla bracelets exchanged for slaves, photo by Mike Peel, 21 February 2010, CC-BY-SA-4.0.

In February, Royal Assent was given to a Charities Act 2022[1] in the UK that will bring new regulations governing museums operating as charitable entities into force over the next three years. Initially, the changes to the Charity Law drew little attention – most had to do with fundraising and the power to use funds raised for one purpose in multiple ways, to give endowments greater flexibility and to more easily amend a Royal Charter or governing document.

However, one apparently minor update to the UK’s charity law may have a far-reaching effect on restitutions of objects to foreign nations and indigenous communities. The new bill grants charities independent authority to make small “ex-gratia” or voluntary gift payments on their own, where a moral obligation can be demonstrated, without first obtaining the UK Charity Commission’s approval. The Charities Act 2022 implementation plan[2] has scheduled these new regulations, listed in Sections 15 on small ex-gratia payments and 16 on the power of the Charity Commission to authorize ex gratia payments to come into force in Autumn 2022.[3]

Law, museum guidance, and advocacy are driving returns.

Many charities can already obtain authorization from the Charity Commission for transfers of art and cultural property for moral reasons, even if the charity’s legal purpose does not specifically include making such returns. That has not been the case for museums created by statutes that limit returns, such as the British Museum – or charities whose foundational charters or trust documents forbid deaccessioning only for ethical reasons.

Pair of silver anklets, Asante (Ashanti), Ghana, before 1874. Museum no 380-1874. Anklets in the form of shackles, possibly representing wealth from the Asante slave trade. Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Some UK museums have already made decisions to return objects on ‘moral’ grounds and have simply sought the endorsement of the Charity Commission for doing so. In early August, the Horniman Museum and Gardens in London announced that it would return 72 objects from Benin to Nigeria. Such decisions are now likely to be conducted according to Arts Council England’s new publication, Restitution and Repatriation: A Practical Guide for Museums in England, its first update in over 20 years.

Both this publication and the Horniman Museum’s decision to repatriate were announced in the period between Boris Johnson’s resignation and installation of Liz Truss and her cabinet, perhaps avoiding a political furor. The Arts Council England’s guidance is more practically oriented and less controversial and politically driven than the Museums Association’s recent publication ‘Supporting decolonization in museums.’

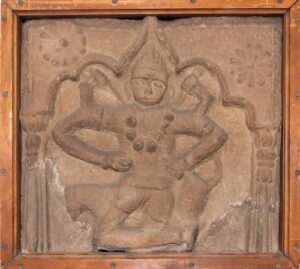

Also in August, Scotland’s Glasgow Museums returned seven objects to India, mostly stone statues taken from temples in the 19th century. Glasgow museums are currently completing the details of a return of 19 Benin bronzes with Nigerian authorities.

An article[4] by Alexander Herman, Director of the Institute of Art and Law, suggests that the Charities Act 2022 could result in even more significant changes in the future, regardless of whether museums are organized as charitable trusts or as national museums (such as the British Museum).[5]

The Charity Bill 2022 states twice in rather convoluted language in Sections 15 and 16 that, “the power conferred by this section is not disapplied only because the legislation concerned prohibits application of property of the charity otherwise than as set out in the legislation.”

Other factors limiting restitution could presumably come into play by virtue of that “only.” Powers could be restricted by trusts; the circumstances might not be “reasonably” regarded as creating a moral obligation. However, as Herman points out, the Charity Bill 2022 does undercut the UK’s High Court’s decision in 2005 in Attorney General v. Trustees of the British Museum, which held that the trustees were prevented from returning drawings to a Holocaust claimant despite having a moral obligation to do so because of the express prohibition in the British Museum Act of 1963.

Pectoral disk, Asante, before 1874, Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Herman states that the Explanatory Notes that accompany the new law make it clear that even charities established by statute, such as the British museum, could delegate decision-making to the Charity Commission and request its authorization to make “ex-gratia” distributions from their collections if they wished to do so. The Explanatory Notes, Section 107 state:

“…it had been decided that the Attorney General had no power to authorise ex gratia payments by a statutory charity. The new section 106(1) creates a stand-alone statutory power for the Charity Commission, court and Attorney General to authorise ex gratia payments. The power can therefore be exercised in relation to any charity, including a charity established and regulated by statute whose governing Act contains a general prohibition on the charity’s assets being used otherwise than for the charity’s purposes.”[6]

No one should expect that there will be a rush to return national treasures such as the Parthenon Marbles – which in many eyes do not qualify as a clear-cut example of a “moral obligation” for return. The Bill grants trustees the power to make ‘morally based ex-gratia payments’ or restitutions on their own only for ‘low value’ objects. The more far-reaching powers to request Charity Commission approvals of return of objects of significant value is also intended to be used with caution by the boards governing charities, who must remain committed to their fundamental charitable purposes as set forth in charters and trusts.

Institutions are taking different approaches, but altogether, these are resulting in a virtual flood of materials, especially to West Africa. Both Oxford and Cambridge universities announced in early August that they were working on a legal transfer of ownership of their holdings of 203 Benin bronzes.

The legislation governing the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, like other national museums, does not allow it to deaccession objects on purely moral or ethical grounds. In September, the V&A announced that it is discussing the return of its Asante gold from the royal court in Kumsai, Ghana. Previous negotiations with Ghana were based upon prospective long-term loans, but the changes to the Charities Law may open other avenues for return.

What does the Charities Act 2022 say?

Indian carved stone returned in 2022, Courtesy Glasgow Museums.

Section 15[7] grants charities a limited power to make ‘payments’ (which could be gifts of objects) up to a certain value “in all the circumstances the charity trustees could reasonably be regarded as being under a moral obligation to take the action.”

Section 16[8] grants the Charity Commission, Attorney General, or a court to authorize a charity’s trustees to take certain actions “(b) in all the circumstances could reasonably be regarded as being under a moral obligation to take it.” This can happen even if a charity is created through legislation that “prohibits application of property of the charity otherwise than as set out in the legislation.” (Both provisions are set forth in full in the endnotes below.)

The value thresholds for ex gratia payments set by the Charities Bill are in fact rather low and based on a charity’s income. For a charity with a gross income of under £25,000, the relevant threshold is £1,000; if over £25,000 but not £250,000, the relevant threshold is £2,500; over £250,000 but not £1 million, the relevant threshold is £10,000; and if the charity’s gross income in its last financial year exceeded £1 million, the relevant threshold is £20,000. However, the bill grants the Secretary of State the power to issue regulations substituting different thresholds.

By redirecting decision-making in part back to museums, the Charities Act 2022 may lift some of the pressure on the UK’s national Charity Commission, which has responsibility for implementing policies affecting the entire range of charitable institutions. The trustees of each institution remain in charge, and the Act makes clear that the trust governing a charity can limit the power to make such payments or distributions. Nonetheless, the tenor of the legislation is to give trustees greater discretion and not to allow charitable institutions to hide behind restrictions in their charters in denying requests for restitution solely based upon provisions prohibiting deaccession of objects in their collections.

[1] Charities Act 2022, 2022 c. 6, https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2022/6/contents/enacted

[2] Charities Act 2022: implementation plan,

[3] The government’s Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport will complete a review of the Act within the statutory review period of 3-5 years following February’s Royal Assent. Charities Act 2022: implementation plan, https://www.gov.uk/guidance/charities-act-2022-implementation-plan

[4] Alexander Herman, Museums, restitution and the new Charities Act, The Institute of Art and Law, 09-25-2022, https://ial.uk.com/museums-restitution-and-the-new-charities-act/; see also Herman, The British Museum must recognize its own powers, The Institute of Art and Law, 06-04-2019, https://ial.uk.com/british-museum-must-recognise-its-own-powers/

[5] The British Museum’s collections retention policy is set forth in the British Museum Act of 1963, which provides in part that the Trustees may sell, exchange or give away any object if it is a duplicate,, made in 1850 or later and substantially of printed matter of which there is a copy, or “the object is unfit to be retained in the collections of the Museum and can be disposed of without detriment to the interests of students.” British Museum Act 1963, Annex 1, 1963 Chapter 24, Article 5(1), See https://www.britishmuseum.org/sites/default/files/2019-10/British-Museum-Act-1963.pdf.

[6] Charities Act 2022, Commentary on provisions of Act, Part 1: Purposes, Powers and Governing Documents, Section 107, https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2022/6/notes/division/6/index.htm

Interior, global display, Horniman Museum and Gardens, photo by Pascal Ebner. Courtesy Horniman Museum and Gardens.

[7] Id. Section 15 states in its entirety:

“Small ex gratia payments – In Part 18 of the Charities Act 2011 (miscellaneous and supplementary), before the italic heading preceding section 332 insert—

“Limited power to make ex gratia payments

331A Limited power for charity trustees to make ex gratia payments etc

(1)The charity trustees of a charity may take any action falling within subsection (2)(a) or (b) if the conditions in subsection (3) are met.

(2) The actions are—

(a) making any application of property of the charity, or

(b) waiving to any extent, on behalf of the charity, its entitlement to receive any property.

(3) The conditions are—

(a) that the value of the property does not exceed the relevant threshold,

(b) that the charity trustees have no power to take the action apart from this section or by virtue of section 106, and

(c) that in all the circumstances the charity trustees could reasonably be regarded as being under a moral obligation to take the action.

(4) The power conferred by this section may be restricted or excluded by the trusts of the charity.

(5) In relation to a charity established by (or whose purposes or functions are set out in) legislation, the power conferred by this section is not disapplied only because the legislation concerned prohibits application of property of the charity otherwise than as set out in the legislation.

(6)For the purposes of subsection (3)(a)—

(a)if the charity’s gross income in its last financial year did not exceed £25,000, the relevant threshold is £1,000;

(b)if the charity’s gross income in its last financial year exceeded £25,000 but not £250,000, the relevant threshold is £2,500;

(c)if the charity’s gross income in its last financial year exceeded £250,000 but not £1 million, the relevant threshold is £10,000;

(d)if the charity’s gross income in its last financial year exceeded £1 million, the relevant threshold is £20,000.

(7)In subsection (5) “legislation” means—

(a) an Act of Parliament;

(b) an Act or Measure of Senedd Cymru;

(c) subordinate legislation (within the meaning of the Interpretation Act 1978) made under an Act of Parliament;

(d) an instrument made under an Act or Measure of Senedd Cymru; or

(e) a Measure of the Church Assembly or of the General Synod of the Church of England.

331B Power to alter sums specified in s.331A

The Secretary of State may by regulations amend section 331A(6) (relevant income thresholds) by substituting a different sum for any sum for the time being specified in that provision.” Charities Act 2022, UK Public General Acts, 2022 c. 6 Part 1, Ex gratia payments, Section 15, https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2022/6/section/15/enacted

[8] Section16 states in its entirety: Power of Commission etc to authorise ex gratia payments etc

“In section 106 of the Charities Act 2011 (power of Commission to authorise ex gratia payments etc)—

(a)for subsection (1) substitute—

“(1)The Commission, the Attorney General or the court may authorise the charity trustees of a charity to take any action falling within subsection (2)(a) or (b) in a case where the charity trustees—

(a)(apart from by virtue of this section or section 331A) have no power to take the action, but

(b)in all the circumstances could reasonably be regarded as being under a moral obligation to take it.

(1A) In relation to a charity established by (or whose purposes or functions are set out in) legislation, subsection (1) is not disapplied only because the legislation concerned prohibits application of property of the charity otherwise than as set out in the legislation.

(1B) In subsection (1A) “legislation” means—

(a) an Act of Parliament;

(b) an Act or Measure of Senedd Cymru;

(c) subordinate legislation (within the meaning of the Interpretation Act 1978) made under an Act of Parliament;

(d) an instrument made under an Act or Measure of Senedd Cymru; or

(e) a Measure of the Church Assembly or of the General Synod of the Church of England.”;

(b) in subsection (3), after second “Commission” insert “by order and”.” Charities Act 2022, UK Public General Acts, 2022 c. 6 Part 1, Ex gratia payments, Section 16, https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2022/6/section/16/enacted

Horniman Museum and Gardens, exterior, Courtesy Horniman Museum.

Horniman Museum and Gardens, exterior, Courtesy Horniman Museum.