On August 30, 2023, Lee Satterfield, the Assistant Secretary of State for Educational and Cultural Affairs and Mohammed Al-Hadhrami, Yemen’s Ambassador to the United States signed a bilateral agreement, or Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) blocking the importation of Yemen’s cultural property into the United States under the Cultural Property Implementation Act (CPIA). It appears that the State Department has entered into a bilateral agreement with Yemen without the required review of the Cultural Property Advisory Committee or public comment.

Assistant Secretary of State for Educational and Cultural Affairs Lee Satterfield and Ambassador of Yemen to the United States Mohammed Al-Hadhrami sign a bilateral cultural property agreement. Credit U.S. Embassy, Sana’a, Yemen.

The original Yemen emergency agreement was extremely rushed and controversial. The announcement that there was a request from Yemen for import restrictions was issued October 2, 2019. There was only two weeks for submission of written public comment and a hearing before CPAC was set for October 29. During the one hour long hearing, American Jewish organizations spoke about how Yemen’s two-thousand-year-old Jewish population was forced to flee the country after the community was subjected to extreme violence as a result of the mid-20th century Arab-Israeli conflict.[1] They told how Yemen’s brutal civil war over the last decade had resulted in attacks on the few remaining Jews and the arrest and imprisonment of Yemenis who tried to help them bring their community’s ancient Torah out of the country.

On December 5, 2019, the Assistant Secretary Educational and Cultural Affairs made the determination that emergency import restrictions were warranted. Organizations opposed to the decision were outraged that the U.S. would sign an agreement with Yemen in the first place, since the forces battling for control of the country and their allies alike were bombing heritage sites and museums. Even more outrageous, under an emergency agreement, U.S. Customs could seize and send Jewish possessions carried by fleeing Yemeni Jews back to Yemen as Yemeni state cultural property.

Dhamar Museum, Yemen, after Saudi airstrikes in 2015.

A few months later, on February 7, 2020, the State Department announced issuance of emergency restrictions. Using vague language of omission, for example, that restricted artifacts “may” have Arabic inscriptions (the State Dept. implied that this would somehow exclude artifacts belonging to Jews) the import restrictions went into effect. The emergency restrictions were due to sunset five years later, on September 11, 2024.

In announcing the original emergency agreement, the State Department stated in the Federal Register that:

“The emergency restrictions are effective for no more than five years from the date of the State Party’s request and may be extended for three years where it is determined that the emergency condition continues to apply with respect to the covered material (19 U.S.C. 2603(c)(3)). These restrictions may also be continued pursuant to an agreement concluded within the meaning of the Act (19 U.S.C. 2603(c)(4)).”

What does this mean? This language refers to a provision for extending an emergency agreement for three years (which the State Department apparently did not seek) or alternately, a provision that allows an emergency agreement to be turned into a bilateral agreement “if before their expiration under paragraph (3), there has entered into force with respect to the archaeological or ethnological materials an agreement under section 2602 of this title or an agreement with a State Party to which the Senate as given its advice and consent to ratification. Such import restrictions may continue to apply or the duration of the agreement.”

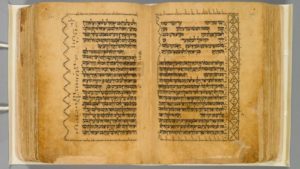

Benayah ben Sa’adyah ben Zechariah. Yemen: 1469. Valmadonna Trust Library, MS 11.

But this didn’t happen either. Section 2602[2] describes the procedure for an ordinary MOU. Since 1983, for the last thirty years, the procedure for signing an MOU under the CPIA has included not only the required Federal Register announcements but also a public hearing in which the Cultural Property Advisory Committee hears testimony from all interested parties.

What’s most shocking about this month’s announcement is that the State Department executed a new bilateral agreement in complete secrecy a year before the emergency agree was due to expire, without a Federal Register announcement of a request from Yemen’s government, or the scheduling of a public hearing before the Cultural Property Advisory Committee, and presumably without a report from the CPAC recommending an agreement or not. And in the case of Yemen, it was made secretly in circumstances in which the State Department unquestionably knew that a public announcement and hearing would result in powerful objections from important American Jewish organizations.

Significant opposition could also be expected to a bilateral agreement with Yemen by other public interest organizations concerned about Yemen’s failure to meet the criteria in the CPIA statute’s four determinations requiring the requesting country to preserve and protect its cultural heritage.

Yemen Embassy Twitter announcement thanking Antiquities Coalition for organizing roundtable. Yemeni Embassy, August 31, 2023.

What’s also alarming is that the State Department welcomed an activist outside organization, the Antiquities Coalition, into their inner circle as a “partner”, for these secret deliberations. The Antiquities Coalition issued its own announcement and social media posts [3] identifying itself as a “partner” with both governments – including one from the Yemeni Embassy that identified the Antiquities Coalition as responsible for setting up a roundtable on the Yemen agreement that included the State Department’s decisionmaker.

What’s also unknown is which NGO “partners” are benefiting from the State Department’s announcement referring to future grants from the U.S. Ambassador’s Fund for Cultural Preservation.

There were no public meetings of CPAC or opportunities for public comment regarding an MOU with Yemen before these announcements were made.

The overreaching of the administration at the State Department’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs (ECA) grows greater and ever more secretive. With each signing of an agreement with a repressive regime that persecutes religious and ethnic minorities, or routinely violates citizens’ human rights, the ECA also appears to act in greater conflict with the policies at State’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor and its Office of International Religious Freedom. It is time for Congress to take a serious look at the ECA’s pursuit of ever more and ever longer MOUs with countries that fail to meet the legal criteria Congress established when it passed the Cultural Property Implementation Act in 1983.

Additional reading: CCP & GHA Testimony on Yemen’s Request for Cultural Property Restrictions, Written Testimony Submitted to Cultural Property Advisory Committee, Department of State Proposed Agreement Between U.S. and Yemen, published October 29, 2019 in Cultural Property News.

[1] There are said to have been 55,000 Jews in Yemen in 1948. There is said to be one only left in the country today. Yemenite Jews, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yemenite_Jews

[2] 19 U.S.C. 2602.

[3] See also https://twitter.com/CombatLooting/status/1697265055060918380 and a post from the Yemen Embassy https://twitter.com/YemenEmbassy_DC/status/1697340568144134215

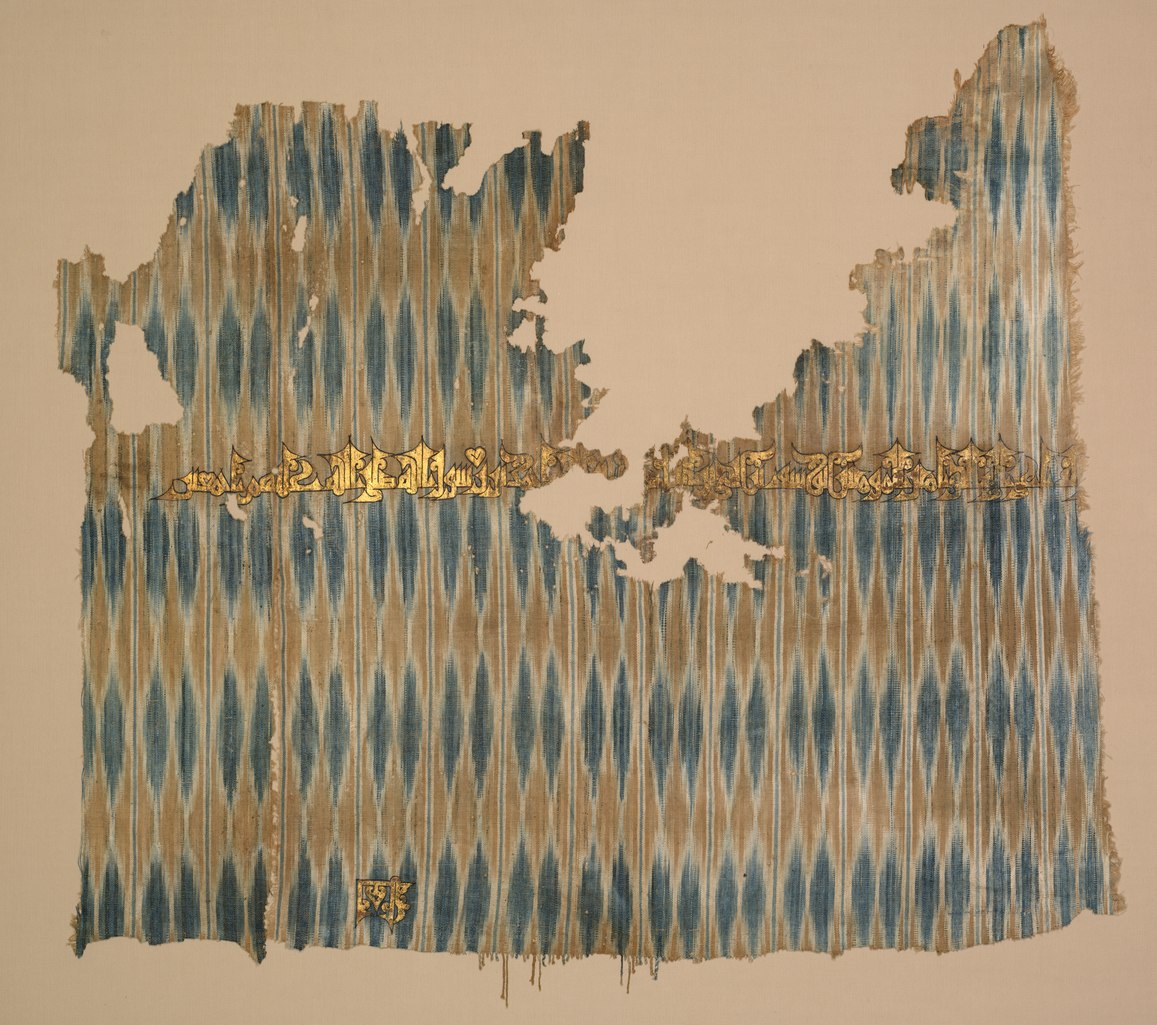

Ikat tiraz textile. Yemen, San'a', Zaydi Imam period, between 960 and 980, Resist-dyed warp (ikat); plain weave with inscription: cotton and gold leaf. This text, written in kufic script with gold paint outlined in black, identifies a ruler of the Yemen: ". . . [a]l-Da’i ila al-Haqq, Commander of the Believers, Yusuf b. Yahya b. al-Nasir li-Din Allah Ahmad, son of the apostle of God, may God bless the all." Cleveland Museum of Art, Accession number 1950.353

Ikat tiraz textile. Yemen, San'a', Zaydi Imam period, between 960 and 980, Resist-dyed warp (ikat); plain weave with inscription: cotton and gold leaf. This text, written in kufic script with gold paint outlined in black, identifies a ruler of the Yemen: ". . . [a]l-Da’i ila al-Haqq, Commander of the Believers, Yusuf b. Yahya b. al-Nasir li-Din Allah Ahmad, son of the apostle of God, may God bless the all." Cleveland Museum of Art, Accession number 1950.353