Updated: 7/12/2020 Turkey’s Council of State has ordered that administration of Hagia Sophia should be transferred from administration by Turkey’s Ministry of Culture to the Presidency of Religious Affairs. This decision was said to be based on Hagia Sophia’s being a trust property managed by a waqf or religious foundation after Sultan Mehmed II’s conquest of Constantinople in 1453. Turkey’s President Erdoğan signed a decree on July 11, 2020 opening Hagia Sophia for Muslim worship.

Turkey’s highest court was scheduled to rule on July 2, 2020 on Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s resurgent plan to convert the 1500 year old Hagia Sophia, the world’s most outstanding extant example of Byzantine architecture, into a mosque. Hagia Sophia is one of the best-known UNESCO World Monuments, and the second most popular museum in Turkey, drawing over three million visitors each year.

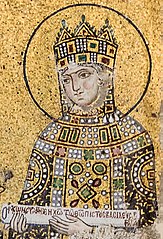

Emperor Constantine I, presenting a model of the Constantinople basilica Hagia Sophia to the Virgin Mary. Detail of the southwestern entrance mosaic in Hagia Sophia (Istanbul, Turkey). January 2013, Photo: Myrabella, Wikimedia Commons

Although Sahak II, the head of the Armenian Apostolic Church in Istanbul failed to object, stating last week that any form of prayer “suits better the spirit of the temple than curious tourists running around to take pictures,” other religious leaders in Turkey and abroad have voiced their opposition. The Greek Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew I said he was “saddened and shaken” by the proposed conversion of the Hagia Sophia to a mosque.

“What can I say as a Christian clergyman and the Greek patriarch in Istanbul? Instead of uniting, a 1,500-year-old heritage is dividing us,” said the Patriarch.

Cultural Property News has written extensively on Turkish law and policies affecting religious minorities (links to these articles in full are below). Readers should note that the Erdoğan government is also threatening the status of other former Christian churches turned into museums in the early 20th century under the secular government of modern Turkey’s founder Kemal Ataturk. These too have been slated to become mosques. President Erdoğan is also building support among extreme nationalists and anti-Semites by pressing forward to eliminate rights to civil and political equality – as well as rights to ownership of community properties such as synagogues and schools – among Turkey’s minority populations of Orthodox Christians and Jews.

The present day Hagia Sophia Museum was originally built as a Greek Orthodox Christian patriarchal basilica in 537 CE during the reign of Justinian. It served as the primary cathedral of Constantinople for centuries. Immediately following the 1453 conquest of Constantinople by Turkish forces, Hagia Sophia (or Aya Sofia) was turned into a mosque.

When the Republic of Turkey was founded in 1923, its first president was Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, who instituted widespread reforms to create a secular country. At Ataturk’s orders, a number of mosques that were formerly Christian cathedrals were converted into museums; the most famous example, Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, was made into a museum in 1935.

Turkey’s General Directorate of Foundations, the agency which administers the Ottoman Empire’s religious endowments, has previously “restored” damaged former churches which also were open as museums and failed to preserve either their ancient architectural features or to enable multi-religious uses. In 2011, for example, the agency reconverted the 5th century St. Sophia basilica in Iznik into a mosque.

The political process that is driving the conversion of Hagia Sophia to a mosque accelerated in 2013, when the Turkish Parliament’s Commission for Petitions considered a request that Istanbul’s Ayasofya Museum be turned into a mosque once again. Reports at the time stated that three Turkish citizens from the northwestern province of Kocaeli appealed to the commission with a petition signed by 400 people to change the status of Hagia Sophia, a request the commission considered seriously. Halil Urun, Acting Chairman of the Commission stated that “no one should be upset about it… compensation was paid [at the time of Mehmet the Conqueror].”

Photo: Mark Ahsman, Dec 2013, Wikimedia Commons

Several times in recent years, Erdogan has urged the conversion of Hagia Sophia and other major monuments of the eastern Orthodox faith from museums into mosques. During a 2013 election, Erdoğan, then Turkey’s Prime Minister, attempted to make Hagia Sophia’s conversion both a religious and nationalist issue in his campaign. A similar campaign in 2014 in Istanbul saw protests organized by Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) party demanding Hagia Sophia’s conversion. Just days before Istanbul’s elections were scheduled on March 31, 2019, President Erdoğan declared that the 1500-year-old Hagia Sophia should be converted back from a museum into a mosque. Erdoğan’s call for Hagia Sofiia’s conversion was repeated several times in 2019.

In March 2019, Erdoğan tied public pronouncements in the Istanbul municipal election campaign for his Justice and Development Party (AKP) to the Christchurch, New Zealand shooter’s stated intention of “removing the minarets of the Hagia Sophia.” He showed the shooter’s footage from the attack, which most news outlets refused to make public, at his election rallies.

Erdoğan’s call to turn Hagia Sophia into a mosque contradicts multiple domestic laws and international undertakings by the government of Turkey. The 1906 Fourth Antiquities Code and 1926 Turkish Civil Code Law No. 1710 protected monuments as state properties, and established parameters for protection of historic buildings such as Hagia Sophia for most of the 20th century. However, by 1983, the management system for cultural properties under these laws was too antiquated to deal with the increasing number of historical sites.

Law No. 2863 of 1983 regarding the Protection of the Cultural and Natural Assets established both a Superior Council and Regional Councils for the Protection of Cultural and Natural Assets. This law places decision-making regarding the physical interference with, and the use or change of purpose of cultural assets, within the scope of the Ministry of Culture and Tourism.

Empress Zoe mosaics (11th-century) in Hagia Sophia, Photo: Myrabella, Wikimedia Commons

Unfortunately, minority religious communities in Turkey have few options to oppose government actions to confiscate or nationalize religious properties. Fearful of reprisal, they often depend on international pressure or foreign diplomacy to protect their interests. In February 2019, Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras visited Hagia Sophia, calling it “an iconic and disputed landmark in Istanbul which has recently been at the centre of tensions between Athens and Ankara over Muslim activity.”

The Lausanne Peace Treaty of 1923 established protection for Turkey’s non-Muslim religious communities, but the treaty specifically identified only three protected religious groups, the Armenian, Greek Orthodox, and Jewish communities. These three have a relatively protected status under the law, although each local community must independently manage its own churches, cemeteries, and community schools under local laws. Other non-Muslim minority groups do not have even this legal recognition. Their situation is so challenging with respect to property that the European Commission for Democracy Through Law recommended in 2010 that Turkey implement legislation to give minority religious communities legal standing.

Minority religious communities in Turkey do not operate under a stable regulatory framework. Only a limited number of legal entities are able to rent or acquire property. Foundations known as vakıfs do not have the legal independence to securely retain properties. In contrast, Muslim communities are able to obtain legal identities and exercise property rights under the aegis of a government agency, the Directorate of Religious Affairs.

In the last decade there have been sporadic efforts by the Turkish government to enable non-Muslim community foundations to regain some properties taken from them in the past. The Restitution Decree of 2011 provided a legal framework under which religious communities whose property had been confiscated by the government could seek to regain it or to obtain compensation for their losses. In January 2019, the first permit ever granted for a church to be constructed in the modern Turkish era was issued for the construction of a Syriac Christian Church in Istanbul.

Photo: Mark Ahsman, Dec 2013, Wikimedia Commons

There have also been some important returns of property. Fifty properties were returned to the Syriac Orthodox Church in Mardin in 2018. These included the oldest surviving Syriac Orthodox monastery, Mor Gabriel Monastery. Other very long-standing disputes regarding properties have not been favorably resolved for the religious communities. The forced removal of Christians from Turkish towns naturally resulted in the closing of schools and other religious institutions, which were then seized by the state because they were deemed nonfunctional. A government decision that a vakıfs is no longer operating has been a common method of expropriation of religious minority communal property.

For example, the Sanasaryan Han in Istanbul was seized by the government in 1936. Due to the forced removal of the Armenian population, the college situated there could no longer operate. In March 2019, the Turkish Court of Cassation announced that it was reversing a lower court decision granting the property to the Armenian Patriarchate. It held that title to the property would remain with the state. A key barrier is that the Patriarchate has still not been able to acquire the status of a vakıfs foundation.

While past Turkish administrations have achieved relatively positive working relationships with the Jewish communities specifically protected under the Lausanne Treaty, the Erdoğan government no longer pursues cooperative relations with Israel, and the Jewish population of Turkey has dropped significantly, placing community ownership of synagogues at risk under the same type of “use it or lose it” government policies.

Today, the fragile remnants of these communities in Turkey remain under extreme political pressure. The Erdoğan government appears unwilling to act to halt anti-Semitic demonstrations and the rise of hate speech against non-Muslim faiths. Despite the protections previously assured under the Turkish Constitution, the failure of the Turkish government to grant full legal status to any faith community after almost 100 years has had a very debilitating effect on the non-Muslim minority religious communities that remain. If Jews, Orthodox Christians, and other religious minorities do wish to leave the country, they must not only be willing to leave behind the most precious tangible relics of their religious communities – export of bibles and Torahs is no longer allowed – but even to lose their ability to voice protests over the politically-motivated conversion of their places of worship to another faith.

Erdoğan’s disdain for international norms regarding the preservation of cultural heritage and recognition of minority people’s rights to religious freedom also argues against granting the Turkish government the ability to block access to virtually all of its art and culture in the U.S. Turkey’s request is pending under the Cultural Property Advisory Committee at the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs at the U.S. State Department.

On 28 January 2018, Syria’s antiquities department and the SOHR, said that Turkish shelling had seriously damaged the ancient temple of Ain Dara at Afrin. This temple was the best preserved Syro-Hittite monument ever excavated. Author Odilia. Wikimedia Commons.

(A request from the Republic of Turkey to block United States importation of Turkish art and ethnographic materials from the Prehistoric Period to 1923 was sought in January 2020. The U.S. law that would enable such a blockade, the Cultural Property Implementation Act (CPIA), was originally used to create limited import restrictions on archaeological materials subject to extensive, current looting. The agreement requested by Turkey is far, far broader and would recognize its government’s ownership of art made over the entire history of the region, while a newly built dam is flooding hundreds of ancient sites inside Turkey and Turkish armed forces are bombing ancient Hittite sites just beyond its borders.)

To find out more: Turkey Claims all Art and Artifacts: Centuries of Multicultural History and Trade Denied, January 7, 2020, the Committee for Cultural Policy and Global Heritage Alliance’s jointly submitted testimony on the Proposed Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) for the imposition of import restrictions between the United States and the Republic of Turkey.

See also Turkish Request Alarms Armenians, Greeks, Turkish Jews, Orthodox and Syriac Christians in Diaspora, December 23, 2019, from which much of this article is drawn.

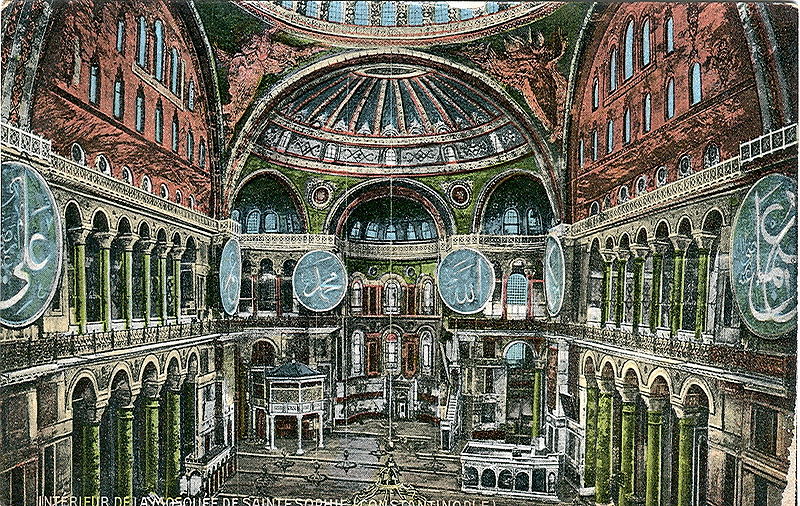

Postcard, undated ( ca.1914 ). Title: "Interior of the mosque of Saint Sophia ( Constantinople ) 13 October 2008, private collection of Wolfgang Sauber (Xenophon), public domain.

Postcard, undated ( ca.1914 ). Title: "Interior of the mosque of Saint Sophia ( Constantinople ) 13 October 2008, private collection of Wolfgang Sauber (Xenophon), public domain.