A confidential letter from Stephen Miller, Chairman of the British Institute at Ankara (BIAA), has revealed that Turkish officials have seized its rare seed collections – including thousands of years old ancient seeds collected from archaeological excavations – and taken them to storage depots at two government-run museums. The raid on

Event at British Institute at Ankara, author MirkoS18, 6 April 2017, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

the British Institute took place September 3, 2020, a year to the day of the issuance of a government decree regulating “the recording, production and marketing of “local” varieties of plant species.” The Turkish government has claimed state ownership over the research collections, which are apparently slated to be used in the “Ata Tohum” or “Ancestral Seed” project that’s being zealously promoted by Emine Erdoğan, wife of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

Staff from the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, the General Directorate for Museums and Heritage from the Ministry of Culture and the Turkish Presidency invaded the British Institute’s Ankara premises and took away 108 boxes of archaeobotanical specimens and four cupboards comprising its entire modern seed reference collections. The British Institute, which is open to academic researchers of all nations, did not respond publicly to the raid until the confidential letter came to light. It has since stated that it is working with Turkish officials to try to ensure the safety and preservation of the collections.

The archaeobotanical specimens and modern seed reference collection of the BIAA were largely founded on the work of late archaeobotanist Gordon Hillman, formerly a professor at the Institute of Archeology, University College London (UCL). Most, but not all, of the seed collection that was held at BIAA is duplicated at UCL.

Cover featuring Turkey’s Crash Wheat Program: Foreign agriculture: weekly magazine of the United States Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agricultural Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, v.5: no.47, 1967.

(Hillman was a “pivotal figure” in the study of archaeobotany worldwide. He worked at the British Institute’s archaeological excavations at Can Hassan III, Asvan, and other sites in Turkey from the late 1960s through early 1970s, and later, on rescue excavations in northern Syria at Tell Abu Hureyra. Hillman developed a new approach to archaeobotany through studying traditional crop processing and built the core seed reference collection for the BIAA and UCL’s Institute of Archaeology. He died in 2018, having taught a generation of students and helped to lay the foundations for modern studies in environmental archaeology.)

Amberin Zaman, who broke the story in Al-Monitor on October 7, 2020, quoted from the confidential letter by Stephen Miller, reporting receipt of a notice from Turkish authorities that the British Institute’s collections belonged to the Turkish state and “would be removed the same day.” According to the letter, Turkish officials refused BIAA’s request for more time in order to minimize the risk of damage or loss to the material.

The raid was officially justified under Turkish government’s decree number 30877 of September 3, 2019, published in the official Resmî Gazete, regulating the recording, production and marketing of “local” varieties of plant species and food producing plants including field crops and “vineyard-orchard” plants. How the British Institute at Ankara’s archaeobotanical seed collection will be used in such a project is unclear.

While there are some examples of ancient seeds, verified through carbon dating, that have been germinated and grown into plants, most experts agree that this is exceedingly rare. Plant and DNA material needed to sustain germination breaks down very quickly, so seeds that are decades old, and even fewer that are hundreds of years old, have the vitality to germinate. Still, seeds found in archaeobotanical assemblages at sites can be deeply informative and provide a cultural context for the site[i]. Another potential value of ancient seeds lies in their DNA, which can allow researchers to study prehistoric food ways and compare characteristics of ancient plants and their modern counterparts.

Agricultural map of Turkey – production of certain agricultural commodities, 1935-1937, dated 1942, United States. Office of Strategic Services. Research and Analysis Branch

Ata Tohum is a project in development since 2017, designed to bring “food sovereignty” to Turkey through the use and development of its indigenous agricultural plants. At its introductory meeting on September 4, 2019, First Lady Erdoğan said “The Ancestor Seed Project is an expression that we see agriculture as the key to our national independence.” She continued: “We obtained 60 tons of product from our ancestral seeds at the first stage. Eleven varieties of products, from melon to Ayaş’s white dwarf tomato, were offered for sale in the stores.”

Political analysts link the project both to President Erdoğan’s increasingly nationalist agenda and a social phenomenon known as Sèvres Syndrome. The term Sèvres Syndrome refers to a nationalist theory, nurtured by Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP), that other countries are conspiring to break up Turkey and weaken its power. Turkish historian Taner Akçam describes this attitude in his book From Empire to Republic: Turkish Nationalism and the Armenian Genocide, as an ongoing perception that “there are forces which continually seek to disperse and destroy us, and it is necessary to defend the state against this danger.” The syndrome’s name derives from the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres, which partitioned the Ottoman Empire between the Kurds, Armenia, Greece, Britain, France, and Italy. Due to Turkey’s victory in the Turkish War of Independence three years later, the divisions in the Treaty of Sèvres were never implemented.

Cover a Turkish Farmer Inspects His Corn, Foreign agriculture :weekly magazine of the United States Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agricultural Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, v.15:no.49, 1977.

Zaman’s Al-Monitor article noted that biochemist and advisor to president Erdoğan, Ibrahim Adnan Saracoglu, who presented at the launch of Ata Tohum following first lady Emine Erdoğan, “railed against assorted Westerners who had plundered Anatolia’s botanical wealth and carried it back home.” Among the culprits accused of stealing seeds was the late American archaeobotanist Jack Harlan, a champion of crop plant biodiversity conservation who collected seeds from around the world for the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s crop plant breeding programs.

“When the power that aimed to alter the genetic makeup of seeds and thereby bring humanity under its own control realized it was wrecking its own soil, it set its sights on Mesopotamia,” Saracoglu said, in a thinly veiled reference to the United States. “Seeds” he intoned, “are the foundation of our national security.”

Asli Aydıntaşbaş, a senior fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations, speaking to The Times, noted another example of Turkey’s claims that hostile foreign nations are attempting to undermine the nation’s security through manipulating its agriculture, this time blaming the Jews, a frequent target of Erdoğan’s AKP. She said “For over a decade now Turkish nationalists have been mulling over a ‘seed conspiracy’ — based on the idea that ‘Israeli seeds’ are pushed upon Turkish farmers in order for them to produce tomatoes, onions or eggplants of a lesser quality, with no smell or taste but bright colours. The theory has now expanded to cover a vast western conspiracy to deprive Turkey of seeds — and is now apparently shared by Erdoğan, who has reinvented himself as a super-nationalist.”

According to The National, diplomats in the UK have demanded that the seed collection seized from the British Institute at Ankara be returned. A spokeswoman from the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office said: “We have raised our concerns about this issue with the relevant authorities in the Turkish Government.”

[i] See, for example, Miller, Naomi. (1999). Seeds, charcoal and archaeological context: interpreting ancient environment and patterns of land use. TÜBA-AR. 2. 15-27.

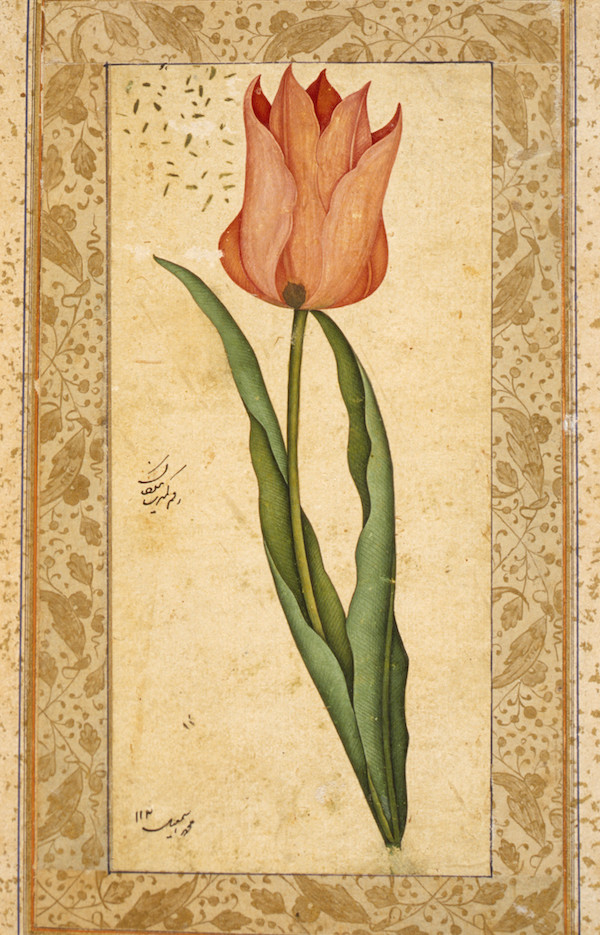

Tulip, Turkey, 1708-1709/1120 A.H.

The Edwin Binney, 3rd, Collection of Turkish Art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Copyright LACMA.

Tulip, Turkey, 1708-1709/1120 A.H.

The Edwin Binney, 3rd, Collection of Turkish Art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Copyright LACMA.