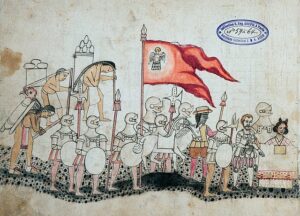

Codex Azcatitlan, Hernán Cortés and Malinche (far right) leading the Spanish army. 16th or 17th century indigenous pictorial manuscript of the conquest of Mexico. Gallica Digital Library, public domain.

An exhibition at the Albuquerque Museum, Traitor, Survivor, Icon: The Legacy of La Malinche is on show until September 4th, 2022. The exhibition, organized by the Denver Museum, presents a wide range of modern and contemporary artwork by international artists, including some from New Mexico, depicting La Malinche, a historical figure from the time of the Spanish invasion of Mexico. As an indigenous woman, collaborator with Spanish forces, and mother of two of the first mestizo children in Mesoamerica, La Malinche’s life and legacy have long been the center of controversies.

What little we know of La Malinche’s life is limited almost entirely to her actions in relation to the Spanish Conquest. Her birth name, hometown, and the events of her early life are all subject to debate and conjecture. The facts of her biography, such as it is, are as follows: she was an indigenous woman, born sometime between 1500 and 1505, in a region outside the immediate control of the Aztec Empire, in what is now Oaxaca. As a child, she was either kidnapped or sold into slavery, to a region where the Chontal Maya language was spoken. She learned to speak one, or possibly two, Maya languages, and also knew several registers of Nahuatl, her native language, including one used by high-ranking members of society, inspiring some historians to identify her as a Nahua noble by birth.

Donna Marina (La Malinche), from “The Mastering of Mexico” by Kate Stephens (1916) New York: The MacMillan Company. Public domain.

La Malinche was one of twenty enslaved women given to Cortés by the Mayan forces after they suffered a severe defeat at Potonchán. Once her language skills were discovered, La Malinche escaped sexual slavery by becoming Cortés’s translator and de facto negotiator with the Nahua and Maya people of Mezoamerica. Her contribution in this role to Cortés’s conquest of the region is considerable; La Malinche is credited (or blamed) from encouraging many communities to lay down arms, rather than be slaughtered by the Spaniards’ superior weaponry. She had one son, Martín, with Cortés, and later married another conquistador, with whom she had a daughter, Maria. She died young, circa 1529. The cause of her death is unknown.

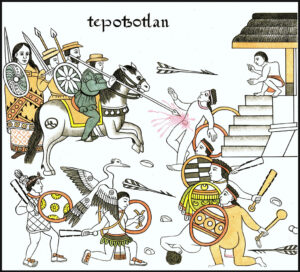

The reconstruction of La Malinche’s life by others began soon after her own death. The two main sources which describe La Malinche’s involvement with Cortés’s invasion force are the memoirs of the conquistador Bernal Diaz del Castillo, and a biography of Cortés written by Francisco López de Gómara. Gómara knew Cortés and drew on his and other conquistador’s accounts for his biography. He never went to the Americas himself, and the accuracy of his account was disputed by contemporaries, including Castillo. Other sources include Tlaxcalan artwork depicting La Malinche in her meetings with their people, as Cortés’s translator, and as a representative of the Conquest in her own right. Neither Spanish nor Tlaxcalan sources are unbiased, for both sides’ perception of and representation of La Malinche are inflected by their understanding of their own roles in the conflict.

Battle of Tepotztotlan depicted in the Lienzo de Tlaxcala, with Marina carrying weapon, circa 1585, Source: Lienzo de Tlaxcala

For hundreds of years, La Malinche’s life has been continuously reinterpreted by historians, novelists, and artists. The Albuquerque Museum’s exhibition retells her life, framing it within both her own historical context, and presenting an overview of how her life and legacy have been rewritten and represented in art over the past five hundred years. The exhibition is divided into five sections, each of which thematize one of the ‘archetypes’ with which La Malinche has been associated over time:

“La Lengua / The Interpreter, which considers her role as translator and interpreter. La Mujer lndigena / The Indigenous Woman explores the archetype of Indigenous women living in pre-Conquest Mexico. La Madre de Mestizaje / The Mother of a Mixed Race presents Malinche as the perceived mother of the mestizo identity of post-Conquest Mexico. La Traidora / The Traitor examines perceptions of her supposed treachery or cultural and ethnic betrayal. Chicana carries her story into the twentieth century when Chicano writers and artists reclaimed Malinche as heroine, survivor, and inspiration.”

Fresco “Cortes y la Malinche” (1926) by José Clemente Orozco, located at Colegio San Ildefonso. México. Public domain.

As this framework suggests, the ways in which La Malinche has been evaluated by Mexican and Indigenous peoples impinge on issues of national, cultural, and gender identity. Despite the loss of her birth name, and the shortage of concrete facts about her life, La Malinche’s presence endures in history, synecdochic of all the indigenous lives touched by the conquest, whose whole histories have since been lost. As the symbolic ancestress of mestizo peoples of Mesoamerica, the consort of Cortés, and as a woman who evaded sexual slavery and achieved both high status and power, La Malinche’s life offers feminist historians and artists a complex view of how female power and female oppression are entwined with global history. As a collaborator with an invading force that was responsible for the destruction of indigenous cultures, La Malinche has been reviled as a culture traitor. Yet in her work as a translator, La Malinche built a bridge between Spanish and Indigenous negotiators, reducing, at least in the short term, the ferocity of the invading forces.

La Malinche encapsulates, in her own person, the tragedies, triumphs, and contradictions that make up modern Mexican identity. Mexico is a multi-ethnic nation, where the descendants of invading and indigenous peoples have lived side by side, mingled their identities, and come together to achieve independence from Spain, and to fight off incursions by American and French forces.

Monumento al Mestizaje” by Julián Martínez y M. Maldonado (1982). Represents Hernan Cortes, La Malinche (Malintzin, or Malinalli, or Doña Marina) and their son, Martín Cortes, commisioned by President Lopez Portillo.Originally it was put in the Center of Coyoacan, near Cortes’ country house, moved to a park due to public protests. The figure of the child has disappeared, probably due to vandalism. Photo 18 April 2009, Author Javier Delgado Rosas.

The complexity of Mexico’s embrace of La Malinche is expressed in the artworks on display, which range from a page from a sixteenth-century codex by an unknown Mesoamerican artist, depicting the invading Spanish forces, to Guadinche (2012), a digital photoprint by Mercedes Gertz, which amalgamates La Malinche and Our Lady of Guadalupe, both maternal figures with deep roots in Mexican identity. Malinche appears as a vulnerable child, as an enslaved woman caught between the patriarchal oppressions of indigenous peoples and conquerors alike, and as the literal foundation for modern Mexico. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Malinche was more often seen as a traitor, complicit in the conquest, than as she is today, as a culture hero, albeit one with a nuanced role in history.

The short, almost unknowable life of La Malinche is engulfed by the centuries of story-telling and art-making that have continuously reshaped that life and its legacy. Oftentimes, moments in history that might otherwise have faded from memory continue to loom large in our consciousness because of the arts. The dramatic de-pedestalling of statues of slave owners and Confederates in America in 2020 is one example of how art speaks to our understanding of history; this exhibition is another. Malinche’s life, played out on both sides of a global conflict, as a trafficked child, an enslaved woman, and finally a translator, negotiator, and mother, challenges simplistic understandings of history. Neither an uncomplicated hero, a Madonna, or a selfish traitor, La Malinche was a woman who lived at a turning point in history. Her complicated role in that history makes it difficult to reduce her to a symbol of a single ideal. That very complexity is what makes her an icon of Mexican history. This exhibition reveals the afterlife of one woman in the culture of the nation she helped to bring into being. In doing so, it sheds a light on the power of the arts to shape a nation’s understanding of its past, and its present.

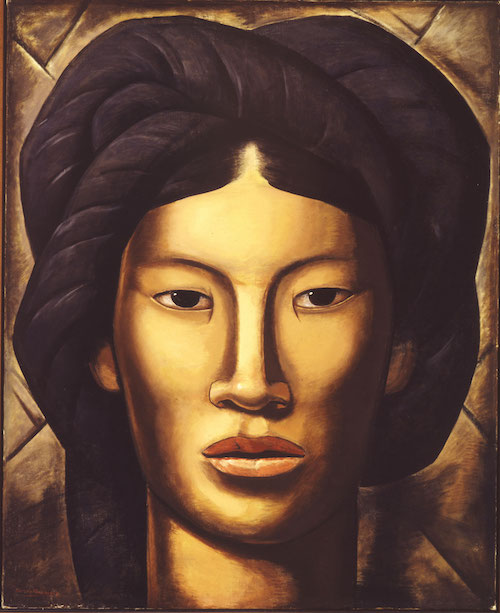

Alfredo Ramos Martínez (Mexican, 1871–1946), La Malinche (Young Girl of Yalala, Oaxaca), 1940. Oil paint on canvas; 50 x 40 1/2 in. Phoenix Art Museum: Museum purchase with funds provided by the Friends of Mexican Art, 1979.86. © The Alfredo Ramos Martínez Research Project.

Alfredo Ramos Martínez (Mexican, 1871–1946), La Malinche (Young Girl of Yalala, Oaxaca), 1940. Oil paint on canvas; 50 x 40 1/2 in. Phoenix Art Museum: Museum purchase with funds provided by the Friends of Mexican Art, 1979.86. © The Alfredo Ramos Martínez Research Project.