On January 1, 2021, amendments to the Bank Secrecy Act were added to define “antiquities dealers” as financial institutions for the purpose of anti-money laundering reporting to U.S. financial authorities. The addition of “antiquities dealers” to the ranks of banks, casinos, and bullion dealers was part of the 1480 page National Defense Authorization Act. The term “antiquities dealers” was not defined in the legislation. This question and many others are now being decided through a regulatory process underway at the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), a bureau of the US Department of the Treasury.[1]

Regulations will spell out what sorts of businesses will be covered and what reporting requirements will be required. The reporting threshold and the amount of documentation that must be submitted by businesses could be based on annual sales or on the size of an individual sale. Information will be collected from sellers when objects are acquired for inventory, and buyers on sale. The business could be required to collect and report identification information, address and contact info, whether the individual is the actual owner of the funds transacted or if they are acting as agent, the actual beneficial owners of corporate entities involved and much more.

Antiquities businesses and others may be required to watch for and report suspicious transactions to FinCEN using SARs (Suspicious Activity Reports) that together with other information submitted to FinCEN, would be made available to police and taxing authorities in numerous foreign countries.

The justifications for imposing money-laundering regulations on antiquities dealers are claims that illegal wealth generated by the antiquities trade is penetrating the U.S. economy and that funds are going to terrorists and criminal enterprises.

Art business and cultural policy organizations submitted written responses to FinCEN answering a range of questions, including:

- What is an antiquity?

- What are the roles, responsibilities, and activities of persons engaged in the trade in antiquities, including, but not limited to, advisors, consultants, dealers, agents, intermediaries, or any other person who engages as a business in the solicitation or the sale of antiquities?

- How are transactions related to the trade in antiquities typically financed and facilitated?

- How do businesses typically operate; what is their size, their gross sales, and the size of individual transactions?

- How much information is gathered about the seller, consigner, or intermediary involved in the sale of antiquities and how much is passed onto the buyer?

- How do foreign-based participants in the antiquities market operate in the US?

- What steps do businesses and others involved in the sale of antiquities take to determine whether the payment comes from a legitimate source?

- What are the money laundering, terrorist financing, sanctions, or other illicit financial activities risks associated with the trade in antiquities?

- What, if any, safeguards does the industry currently have in place to protect against money laundering, criminal association, business loss and fraud?

- At what threshold should FinCEN require reporting of trade in antiquities? Should there be any other exemptions?

- What are the challenges to obtaining information to meet reporting requirements?

Organizations arguing for the most burdensome reporting from the art and antiquities trade frequently cite to its “secrecy” and “impenetrability.” They say that confidentiality means there is something to conceal – and that the trade is covering an enormous illicit market worth hundreds of millions to billions of dollars benefiting criminals, terrorists, and other evildoers.

The trade has provided reams of data to FinCEN showing that this is not true. It has made clear that antiquities form the smallest sector of the art market, however they are defined, whether they are businesses selling ancient, Classical, Renaissance, Islamic, Asian, ethnographic or antique Native American art, coins, books or manuscripts.

Laurent de La Hyre (1606–1656) Allegory of Dialectic, 1650.

The trade comments show that the vast majority of businesses in these sectors qualify as micro-businesses with fewer than ten employees – often they have fewer than five. They operate in a highly regulated banking environment whether they operate only in the US or overseas; they trade in countries with similar monetary regulations such as the UK, the EU, Japan and Australia. Their inventory turns over slowly, their clients are academically minded rather than fashionable celebrities, and their markets are limited.

All trade categories noted that this business model is not suited to money laundering. As antiquities dealer Randall Hixenbaugh told the New York Times, “Criminals seeking to launder ill-gotten funds could hardly pick a worse commodity than antiquities.”

Most respondents defined an “antiquity” as dating to 500 AD or earlier; none feel it is appropriate to include anything later than 1500 AD. Many answers to the questions about business practices posed by FinCEN are consistent between industries. For example, large transactions are by check or bank wire. Cash transactions in amounts over $10,000 are virtually unknown. Dealers maintain close relationships with clients and know their special interests; a buyer for an expensive item who was not knowledgeable in the field would stick out immediately as suspicious.

Foreign-based dealers almost always operate directly with US dealers, not through intermediaries. Unlike the contemporary art milieu, advisors, consultants, agents, intermediaries, or persons other than dealers rarely exist in antiquities-based industries. The risk of money laundering in any of the described industries is negligible. Most transactions are between people who have known each other for years, if not decades. All industry responses noted that both dealers and buyers were aging, this is an elderly demographic in which a younger collector was a rarity.

We have also provided quotes from and links to comments submitted by proponents of stringent regulation. The most extreme of these was submitted by the Clooney Foundation for Justice. Like the submission of the Antiquities Coalition, it recommends the term “antiquities” mirror the full description of “cultural property” in the 1970 UNESCO Convention (which includes floral specimens, photographs, virtually all art, antique furniture, books, ethnographic and folk items, coins, currency, and postage stamps). It also recommends that the definition of “antiquities” reflect provisions of the UNIDROIT Convention, which the U.S. has not signed. The Clooney Foundation recommends setting no dollar or age threshold whatsoever for reporting by dealers in any of the above types of goods and the filing of Suspicious Activities Reports for all transactions, with more detailed reporting than normally required by FinCEN.

The extracts below and linked full texts, were submitted to FinCEN in response to the public commentary process under an Advance Notice of Public Rulemaking issued on September 23, 2021, to implement Section 6110 of the Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020.

All the comments submitted to FinCEN are linked here. We have provided direct links for the organizations listed below, as the FinCEN system does not make the names of submitters immediately clear; readers must use the search tool or go through all 37 comments.

CINOA (Confédération Internationale des Négociants en Œuvres d’Art)

Isaak van den Blocke (1575–1626) Allegory of Gdańsk trade, 1608, Pafond (ceiling painting) in the Red Hall of the Main Town Hall in Gdańsk. Wikimedia Commons.

“CINOA is the principal international confederation of Art & Antique art market professional associations, an umbrella for 30 leading dealer associations in specialties from antiquities to contemporary art…CINOA’s associate members, include leading associations of auction houses and the International League of Antiquarian Booksellers (ILAB), which alone represents an additional 22 book seller associations. It is the largest representative of art market professionals and its recommendations are the result of market analysis discussions with market stakeholders.” (f.1)

“[CINOA calls] for a proportionate, risk-based approach to AML legislation implementation. The cost of compliance with BSA requirements would represent a significant financial burden as well as threaten the survival of many micro-businesses. To mitigate the damage to the sector, clear risk criteria and a monetary transaction threshold should be established by regulators, otherwise all businesses dealing in antiquities, which are for the most part micro-businesses involved in low risk transactions, would be subject to BSA compliance… these micro-businesses consisting on average of two to four individuals, would be required to comply with the same anti-money laundering obligations as a large financial institution.” (p.2)

CINOA stated that, “the scope of ‘illicit activity’ involving antiquities has been highly exaggerated by advocates of implementing such controls. Sensationalized headlines about illicit trade abound. However, they are not supported by the data on the trade in general, or specific details of cases of illicit trade… Regulatory choices should be made based on factual economic data and actual evidence of crime. Instead of relying on unfounded information, FinCEN should utilize the work of recognized, independent sources such as the RAND report.” (p.2)

“[N]either the asset class, nor market liquidity comparisons are valid… compared to bullion or diamond dealers.” (p.2)

“Antiquities dealers have very slow turnovers in the objects they offer for sale and auction results confirm that even at the highest echelons of the market, where there is an international clientele, approximately 25% of antiquities still do not find a buyer. Antiquities are not considered an investment vehicle and purchasers of high value items cannot expect a financial return. Buyers tend to be scholarly and very well informed of the legal issues surrounding them.” (p.2)

- “Today’s antiquities market is made up almost entirely of bricks-and-mortar businesses which do not have access to the resources necessary to implement sophisticated compliance programs. These micro-businesses have thin margins and semi-illiquid assets.” (p.3)

- “The only antiquities businesses today which could be considered “sizable” are auction houses. These established businesses follow customer and item due diligence rules tailored to the origin and value of the item, the client, the market demands, available data, and resources. Dealers have codes of professional standards and auction houses implement voluntary compliance protocol worldwide, both of which are aligned with AML practices.” (p.3)

- “Objects which can be linked to a conflict zone, either by the objects’ origin or through direct links of the purchaser and seller to a conflict zone, are already considered a ‘higher-risk’ object for transaction by the art trade.” (p.3)

Importation of objects from high risk MENA countries “would already be subject to seizure at Customs for lack of documentation under Memoranda of Understanding with virtually every country surrounding the Mediterranean, including not only countries such as Iraq, Syria or Libya but also transit points such as Turkey or those in North Africa… CINOA recognizes that it could be appropriate to subject to the BSA regulation transactions involving objects or persons from these higher risk geographical areas, because of the potential links to financing of conflicts.” (p.4)

“There is a high cost of known compliance for small businesses (estimates range from $2,000-5,000 per year for small businesses. The practicalities of these obligations require dedicated resources and an adequate infrastructure to implement them, neither of which most micro-business have available.” (p.4)

“The costs would far outweigh any of the proposed benefits….” “Therefore, to mitigate any unnecessary BSA obligations for antiquities, a concentration on only higher-risk and ‘high-value’ transactions would seem to be applicable. We see that a reasonable price threshold should be set above $500,000. For amounts under $500,000, additional compliance implemented would be unlikely to help in the detection of elaborate high-value cover up schemes.” (p.4)

“Exemptions should be available to established business with credentials that fulfill a number of criteria, such as:

- Business with an annual turnover of less than $1 million;

- Businesses that are a member of a professional trade organization, such as CINOA;

- The antiquities or transaction participants are not linked to a conflict zone.” (p.6)

“The art market would welcome actual data on money laundering transactions involving antiquities that is known to date being made publicly available. Data on past seizures in Europe, particularly in Italy, is not available to the art market, to museums or to consumers even 15-20 years after seizures have been made. The withholding of this information is a serious barrier to due diligence actions by the market and consumers.” (p.7)

Rudolph Ernst, The Moorish Bazaar.

“Historically, the US has not accepted the characterization of what is an antiquity or what rules the US will apply to them based upon foreign law. “In the US “Convention on Cultural Property Implementation Act”, the Senate Committee Report 97-564 (1982) states… that Congress placed constraints on executive power hoping to ensure that the United States exercises its “independent judgment” in defining cultural property. As the Senate Committee Report 97-564 at 6 (1982) explains,

“The Committee intends these limitations to ensure that the United States will reach an independent judgment regarding the need and scope of import controls. That is, U.S. actions need not be coextensive with the broadest declarations of ownership and historical or scientific value made by other nations.

U.S. actions in these complex matters should not be bound by the characterization of other countries, and these other countries should have the benefit of knowing what minimum showing is required to obtain the full range of U.S. cooperation authorized by this bill.” (p.8)

“There is legitimate concern that, with new corporate transparency laws also being implemented on a much larger scale, the government would be in a position to potentially misuse data collected on legitimate collectors and dealers. More specifically, that information collected to prevent money laundering could be acquired by parties exclusively interested in forcing the repatriation of objects to countries with a reputation for authoritarian governance and broad cultural patrimony laws which treat any man-made object from within their state borders as ‘cultural property.’ Since some nations with a history of licensed trade up to 1983 (for example, Egypt) now claim objects exported in the 19th century, this is a legitimate concern.” (p.8)

“Estimated Figures Regarding Art Market Sales and Antiquities

- a) The last known study of the antiquities portion of the global art market was compiled in 2013 by the IADAA. The IADAA study was able to identify a worldwide antiquities market total of about €133 million EUR (~$184 million USD as of December 31, 2013). This figure arose from canvassing IADAA members, analyzing auction results, and assessing sales by dealers with physical premises in 2013. Per a consideration that perhaps the total antiquities market had not been accounted for, IADAA brought their approximation up from €133 million EUR (~$184 million USD as of December 31, 2013) to a range of between €150-200 million EUR (~$200-275 million USD as of December 31, 2013).

- b) Of the €133 million EUR global antiquities figure identified by the IADAA, U.S. sales accounted for €50 million EUR (~$70 million USD as of December 31, 2013). By applying the same ‘consideration’ metric—which brought the total from €133 million EUR up to €150-200 million EUR—we can round the €50 million EUR (~$70 million USD) portion of U.S. antiquities sales up to about €55-75 million EUR (~$75-$100 million USD as of December 31, 2013) to account for a high-end estimate of the U.S. market’s total sales in antiquities in 2013 dollars.” (p.11)

Daniel Gran (1694–1757), Allegory of War and Law, completed 1730, Austrian National Library, Prunksaal (splendor hall). The splendor hall of the Austrian National Library was designed and started by Johann Fischer von Erlach and finished by his son Joseph Emanuel in 1726.

“In May of 2020, a study commissioned by the U.S. Department of Defense into ‘Illicit Antiquities’ was published by RAND, which is considered the leading independent research organization in the United States, with a 75-year history of ground-breaking studies. Titled ‘Tracking and Disrupting the Illicit Antiquities Trade with Open-Source Data’, it concludes that the most widely held assumptions and current theories are wrong about antiquities trafficking, and the role of antiquities in terrorist financing. According to the study, available research suffers from analytical weaknesses, in part due to a lack of stable definitions. “Researchers have sought to compensate for the lack of specialized data on antiquities trafficking by borrowing theoretical models, statistical data, and empirical evidence from the literature on cultural goods—a field that includes antiquities but often focuses on the visual arts. Greater care is needed to explain the specific characteristics of the antiquities trade, define the limitations of the available data, and avoid unintentional or misleading conflations between distinct categories of trade.” (RAND, p. 9).” (p.14-15)

“RAND researchers conclude that it was unlikely that looted, or illegally excavated, artifacts (from their survey in Iraq and Syria) ever go beyond neighboring countries in the Middle East. The evidence for this is that items appear to be sold for their ‘international market price’ very early in the supply chain. The RAND Study notes that if “collectors in Turkey and Iran are buying these items for prices similar to what they would attract in the United States, then there is less opportunity for importers and dealers to make money through arbitrage than has traditionally been assumed.” (RAND, p. 26-27). On the demand side, RAND’s analysis is supported by research published through the University of Chicago Law School’s Journal of Law and Economics in 2016, which illustrated how, since at least 2005, objects with a strong, well-documented provenance command a significant premium over those which the provenance (or evidence of an extensive history of circulation in the legitimate market space) does not exist. (University of Chicago, Journal of Law and Economics, vol. 59; 2016, p. 2). All this confirms that there is little to no correlation between the looting, or illicit excavation of ancient objects, and the market demand for objects which can be defined as ‘antiquities.” (p.15-16)

“Typically, some six months after a piece was purchased by an art market professional, it may end up being offered for sale. If a potential buyer materializes, they will ask to see the accumulated paperwork for the piece(s) and if dissatisfied with a lack of documentation, will reject the object. Export documents, import documents, written statements, publication in an auction catalog, and Art Loss Register search certificates are all touchpoints by today’s collector. When such documents are available, such as a handwritten receipt from a licensed Cairo dealer of the 1970s it rarely accurately describes the object in detail. The vast majority of legally acquired antiquities that reemerge from old collections no longer have any paperwork regarding the original importation. The last refuge of the inheritor of antiquities seeking to disperse a collection is to donate it to a local museum. However, the current guidelines of the Association of Art Museum Directors prohibit many museums from accepting donations of archaeological material that was not published photographically prior to 1971 (Hixenbaugh, 2019).” (p.17)

“According to the study conducted by RAND, a survey of dealers in the United Kingdom suggests that there are roughly 25 high-end antiquities dealers operating in the UK. The UK’s Antiquities Dealers Association lists 24 affiliated dealers selling or buying antiquities throughout England. This list can be taken to exclude some smaller, unaffiliated dealers. An international professionals’ group, the International Association of Ancient Art Dealers (IADAA), lists 26 members—located in Europe and North America—on their website. Although these are rough estimates, and the search parameters could be improved to potentially better capture galleries that deal in antiquities, these numbers suggest that there may be fewer than 100 principal antiquities dealers operating in the whole of North America and Europe (RAND, p. 73).” (p.20)

IAPN and PNG (International Association of Professional Numismatists and the Professional Numismatists Guild)

“[We] write on behalf of 7-10 million serious American coin collectors and approximately 5,000 micro or small businesses that buy and sell historical coins. Regulations meant for antiquities dealers should not apply to coin dealers. The antiquities and numismatic trade are distinct. Concerns about money laundering, terrorist financing, and other illicit financial activities should be negligible.” (p.1)

Marinus van Reymerswale, Money changers, first half of the 16th c, The Hermitage.

“Collectors’ coins are not liquid assets like bullion…The United Kingdom’s Treasury Department exempted coin dealers from its recent anti-money laundering regulations, and FinCEN should do so as well.” (p.2)

“Profit margins are small compared to other collectibles… Christie’s and Sotheby’s no longer hold regular sales of coins… Some [auction houses], though still defined as small businesses under the Small Business Administration’s (“SBA’s”) criteria, employ hundreds of employees and have annual sales of $100 million. Most numismatic auction houses… have annual sales in the $5-30 million range.” (p.4)

“Most US based coin dealers are small or micro businesses with sales under $1 million… sole proprietorships with one or two employees, and approximately two-thirds operate as part-time businesses as an adjunct to their owner’s collecting interests… Most dealers sell coins valued from $20 to a few hundred dollars each. Comparatively few coins are worth over $50,000. These are mostly rare Roman gold coins, rare high grade Greek silver and gold coins, and certain rare American and foreign coins in excellent states of preservation. That said, collectors and especially dealers often purchase multiple coins at once, particularly at auction. Moreover, given the large numbers of collectors and coins available for sale, the total value of the market is estimated at $3 billion.” (p.5)

“The reason most coins do not have provenance information attached to them is quite innocent; it was not thought important until a few years ago, particularly for low value specimens.” (p.6)

“[D]ealers regularly retain information about buyers and sellers, but there is concern about making this information available publicly because of concerns about privacy and theft. For sellers, there may be added reasons for privacy when such sales are associated with financial distress.” (p.7)

“[A] major auction house which also auctions other objects gave the following information for ancient coins: “[I]n 2020 we sold 14,927 lots that we identify as ‘ancient.’ Of those, 13,298 (89.09%) sold for less than $1,000 hammer, meaning 1,629 (10.91%) sold for $1000 or more. While the average hammer price was approximately $679, the median lot price was $240. When you factor in the fact that a lot of those lower value lots were actually group lots, the median [price of] ancient coin[s] sold … in 2020 was under $200. A single ancient coin selling for over $50,000 is an unusual occurrence, and this [amount for a single item] may be the more reasonable and practical threshold at which further scrutiny is triggered. Looking at our same data from 2020 as noted above, we had only 5 ancient coin lots hammer for $50,000 or more, totaling $400,000, which represent 0.03% by volume and 3.96% by value of our overall ancient coin sales in 2020.” (p.10)

“…a major numismatic auction house with a specialty in ancient coins, compiled an approximate breakdown of annual sales for coins dated before 1500 AD. Although this represents only a single dealer’s sales, we think that the figures are generally representative of the breakdown of sale levels for the larger dealers in the trade. The following approximate figures are from the most recent year and include only coins dated before 1500 AD:

- Number of items sold for up to $1000: 18,030

- Number of items sold for $1001-$10,000: 4,709

- Number of items sold for $10,001-$100,000: 499

- Number of items sold for $100,001-$500,000: 17

- Number of items sold for $500,001-$1,000,000: 1

- Number of items sold for more than $1,000,000: 0” (p.10-11)

Goudweger, Salomon Koninck, 1654.

“If US auction houses and dealers had to disclose the identities of their sources, competitors abroad would consider it an open invitation to then contact those persons and attempt to take their business. This would put US firms at a dramatic disadvantage to their foreign competitors, none of whom is required to disclose such information… If US dealers are no longer able to offer confidentiality, a very substantial proportion of business would move abroad. (p.12)

“In the EU… it would be a breach of data protection laws to disclose the personal information of a person (such as an auction consignor) without that person’s permission. See the General Data Protection Regulation. These rules also apply to US entities that disclose the personal information of EU residents. Other countries outside the EU, such as the UK, also have similar rules.” (p.12)

“Coin collecting had its heyday in the United States in the 1960s and the hobby has greyed considerably since then. Most coin collectors are middle aged or elderly. Most have decades long relationships with dealers, who also tend to be middle aged or elderly.” (p.14)

“Until at least the 1980s, there were open markets for ancient coins throughout the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), Pakistan, and Afghanistan, and we understand ancient coins are still sold quite openly in at least Israel, Jordan and Lebanon. Today, any risks of money laundering, terrorist financing, and other illicit financing risks would be related to direct purchases of coins from the MENA region or conflict areas like Afghanistan. Coins struck in those areas thousands of years ago now on the market in Europe, Australia, Canada, Japan and New Zealand would likely not carry such risks.” (p.15)

“IAPN and PNG both have codes of conduct which include guarantees of good title and authenticity.” (p.17)

“The risks inherent in commercial, for-profit trade in antiquities may on occasion be less significant than the risks inherent in what is billed as non-commercial, not-for-profit activity. For example, archaeological groups, which successfully lobbied Congress to make “antiquity dealers” subject to Bank Secrecy Act (“BSA”) requirements, represent archaeologists who must seek government approvals to excavate antiquities in MENA countries where there are heightened dangers of bribery, money laundering, terrorist financing and other illicit activity. Moreover, some of these advocacy groups have partnered with MENA governments which are fraught with corruption. This is not to suggest these groups are involved in illicit activity. Rather, the Numismatic Trade simply notes that archaeologists often operate in geographical and political environments far more fraught with these problems. In contrast, the micro and small businesses of the coin trade have longstanding business ties here in the United States and do the vast majority of their foreign business in the regulated markets of Europe.” (p.22)

“We suggest a threshold of over $10 million in gross sales and purchases per year. Alternatively, compliance requirements could be triggered where there are over $1 million in purchases or sales from an individual per year. If thresholds by item are contemplated instead, $50,000 per transaction would be a far more reasonable figure than the €10,000 threshold under EU regulations. With inflation, that threshold may become too low over time.” (p.24)

“IAPN and PNG believe that beneficial ownership requirements should be applied generally and not specifically to the trade of antiquities. IAPN and PNG also do not believe they should be applied to transactions with antiquities dealers that have established offices and mailing addresses.” (p.26)

ATADA (Authentic Tribal Art Dealers Association)

“ATADA is the largest organization of Native American tribal and international ethnographic art dealers in the United States, with 342 active members. It is the only U.S. art business organization representing dealers in antique and ancient Native American art.” (p.1)

“There has been no evidence of any association of the U.S. trade in antiquities in general with terrorism, drugs or the Dark Web. Serious studies such as the RAND Corporation’s Tracking and Disrupting the Illicit Antiquities Trade with Open Source Data, have identified the sources responsible for promoting this misinformation in the press as being the same advocacy organizations presently partnering with AML service providers and urging regulation of the entire art trade.” (p.2)

“It is not clear that our industry should be considered within the term “antiquities dealers.” The term “antiquities” is not generally used to describe tribal or ethnographic art.

There are two primary components of the ethnographic art trade, which are:

- the trade in American Indian, Alaskan, and Hawaiian art, new, antique, and ancient;

- the trade in antique international ethnographic art.

Detail of ledger painting on muslin by Kiowa artist Silver Horn (1860-1940), ca. 1880, Oklahoma History Center.

Neither of these two categories are generally considered antiquities. Most Native American artworks in trade have been made in the last 150 years… Most international ethnological artworks in trade were made in the last 250 years. Almost none are signed or dated. Although very occasionally, items are found that can be carbon-dated through scientific testing that are up to 600 or 1000 years old, there is not a historical sequence to distinguish early evidence of non-industrial, more primitive ethnological materials from more recent production. Scientific carbon dating costs hundreds of dollars and is rarely worth performing.” (p.3)

“The United Kingdom excludes tribal antiques and ethnographic art from the purview of its own anti-money laundering regulations. The U.S. should seek to use harmonized definitions for international trade purposes.” (p.5)

“The international auction market captures much of the most valuable tribal and ethnographic artwork sold globally. The ARTKHADE 2021 Report is the tribal art industries’ closest equivalent to the ArtNet and Art Basel and UBS Global Art Market Report that provide global business analyses for the total art trade. (These other art business analyses do not even include antiquities and tribal art in their reporting, except as an “other” category including furniture and silver, whose total value of the art trade is less than one percent globally.) The first paragraph of the 2021 Report states that despite what were considered bumper sales in recent years, €58.5 million in 2019 and €76.3 million in 2018, the total annual sales of tribal art at global auction in 2020 was just €32.1 million. Native American art from North America (Canada and the U.S. combined) was €3.3m of the total. By category, total global ethnographic auction sales in 2020 were measured as:

- African art €18.3million

- Oceanian art €5m

- South American €4.5m

- North American €3.3m

- Asian €856,520” (p.6)

“Between 84% and 96% of the tribal objects in every geographical category at global auction sold for less than €10,000. Less than 1% of any category sold for €50,000 or more, and only one category, African tribal sculpture had any sales larger than €500,000; less than one tenth of one percent (.09%) of objects were high value.” (p.8)

“The most expensive Native American artworks ever sold, at auction or gallery sale, have values of from $1-3 million dollars. (Historically, at most one or two extraordinary items per year have reached a value of $1,000,000 or more and prices have been going down for the last decade.)” (p.11)

“Gallery and antique business sales, together with annual art fairs in Santa Fe, San Francisco and New York in the United States dominate the lower end of Native American art market. Average sale prices in these markets range from $100.00 to $5,000.00 per antique/ancient object, with an average between $500-$1000.00.” (p.8)

Amedeo Preziosi (1816–1882) A Turkish Bazaar, 19th century, public domain.

“Thus, the antique/ancient art market in international tribal and Native American art in the U.S. is negligible compared to the market in modern art, in which it is not unusual for a single contemporary painting to sell for $100 million – more than twice the total annual sales of ethnographic art at auction globally.” (p.8)

“All of the businesses in the ethnographic art industry are considered micro-businesses. Most businesses are single-individual operated; commonly spouses work together as a family enterprise or with 1-5 employees. For almost all these businesses, revenues are well under $1 million per annum. Many earn under $100,000 per annum.” (p.8)

“Smaller auction houses and fair operators employ fewer than ten permanent employees. Larger auction houses in which Native American art is only one among several dozen categories of art may have several hundred staff members but only hold 2-3 American Indian auctions per year. International ethnographic art auction sales are even less frequent, as many Americans collect Native American and Western art and very few collect international tribal art.” (p.9)

“There are estimated to be at least one hundred thousand small U.S. hobbyist collectors of ancient and antique arrowheads and “points” (larger stone spearheads and knives). There are collector organizations in every state. Many engage as small-time traders as a means of improving their collections. Collectors and professional traders often meet in local fairs for enthusiasts, where traders rent a table for a small fee.” (p.9)

“Both market dealers and market buyers are aging; buyers are usually in their 60s and 70s and there is very little interest in this art among younger buyers. ATADA member dealers, with only a half dozen exceptions, are retirement age or older. As a result, there is a surplus of goods for sale, the vast majority of it recycled from older collections, and prices are dropping.” (p.11)

“In the last decade, at least three of the largest and most valuable collections of ancient (400-1000 years old) and historic (100-200 years old) ceramics and other Native American art have been donated by their owners to American museums and thus removed forever from the market.” (p.11)

[If ethnographic art is covered] “their $50,000 gross business per year threshold is far too low. This threshold would incorporate most viable businesses; as a large number of smaller businesses are in the $50,000-$100,000 annual range, the costs and time associated with preparing and maintaining an anti-money laundering program and an annual independent audit would be sufficient to push many small businesses into unprofitability. It makes more sense to have a much higher threshold over $10,000,000 gross or purchases or sales whose values total over $1,000,000 annually.” (p.12)

“There should be exemptions for business transactions conducted by check, bank wire, or credit card within the US, and with countries with well-developed banking systems like Australia, Canada, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore, UK, EU, and Switzerland.” (p.13)

GLOBAL HERITAGE ALLIANCE (GHA)

Bernardino Mei (1612–1676) Allegory of Justice, 1656.

“ When this matter was before Congress, GHA supported a Senate Banking Committee alternative that would have studied the extent to which antiquities were utilized to fund terrorist and other criminal activity before authorizing FinCEN to regulate the industry. Such caution was warranted given the shifting nature of the justifications for anti-money laundering (AML) regulations being imposed on the antiquities industry. First, the legislation’s proponents, a coalition of archaeological advocacy groups and AML compliance contractors, claimed that the legislation was necessary to help keep items looted by Islamic State terrorists off the market. Next, after those claims were debunked, proponents of the regulations cited reports that criminals were exploiting the art market to launder money. Specifically, they latched onto a Senate report detailing a highly unusual set of facts involving Russian oligarchs evading sanctions with the purchase of valuable paintings through shell companies and a Moscow based art intermediary as the reason to regulate an entire industry. Even more recently, they have cited reports that the family of Douglas Latchford, a deceased Thai antiquities dealer, used offshore trust accounts to hide profits from the looting of Cambodian archaeological sites dating back to the immediate aftermath of the Vietnam War as further justification for clamping down on American antiquities dealers.” (p.1-2)

“In fact, Global Financial Integrity’s report on transnational crime indicates that cultural goods account for no more than 0.1% of illegal activity. Given the variety of industries where money laundering is thought to be a far more serious problem, GHA believes caution is in order before FinCEN issues regulations which may harm legitimate trade in the United States.” (p.2)

“Efforts to justify regulations based on jewelers and bullion dealers already complying with similar rules, or arguments that the art trade in Europe is covered, should also fail. Jewelry and bullion are liquid commodities easy to launder. Antiquities take time to buy and sell, making them a poor vehicle for money laundering. Just because European regulators acted precipitously, based on questionable information about the Islamic State being financed by stolen antiquities, does not mean that US regulators should do so as well.” (p.2-3)

“The costs also should not be underestimated. Proponents avoid speaking about such costs because they know how devastating they would be to businesses already operating in a very difficult business climate. House Financial Services staff have indicated that any regulation of antiquities dealers under the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) would most likely be similar to that covering jewelers and bullion dealers. Virtually all such viable businesses are covered given the $50,000 gross per year regulatory threshold. Once covered, jewelers and bullion dealers must spend thousands of dollars per year in compliance costs for an AML plan, and an independent audit, and considerable time on red tape. Such money, time and effort could very well drive marginal businesses under, particularly those operating part time.” (p.3)

“Moreover, regulations already applicable to industries that deal in high value, liquid assets like bullion have been heavily criticized because the costs to micro and small business are grossly disproportionate to any successes in stemming money laundering. Such concerns will be magnified for the micro and small businesses of the antiquities trade which has just begun the process of recovery from Covid-19 business disruptions.” (p.3-4)

Hans Makart, Allegory of the Law and Truth of Representation (1881 – 1884), Google Art Project.

“The legislation making antiquities dealers subject to the Bank Secrecy Act was enacted before there was any evidence showing that money laundering in the antiquities market was actually a problem. The legislation was based instead on a variety of unsupported allegations. Over the last several years, anti-antiquities trade advocates have made well-publicized but unsubstantiated claims about terrorist connections and the supposed enormous size of the antiquities market. The most prominent among these advocates, the Antiquities Coalition, has alleged that terrorists receive significant funding from an illicit market in global antiquities; they have also claimed that the illicit antiquities trade amounts to ten billion dollars a year or more in value. They have never provided hard evidence for these claims.” (p.2)

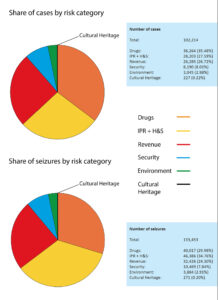

Pie charts showing share of cases by risk category, and share of seizures by risk category; information drawn from the World Customs Organization, Enforcement and Compliance, Illicit Trade Report 2019. © Ivan Macquisten. (p.5) [Ed Note: WCO figures shown encompass all cultural good, so antiquities are an even smaller share than represented.]

“The antiquities market is the most highly scrutinized category of artworks, although it is the smallest of the global art market categories, less than 1% of the art market by value. Art market reports divide art into general categories. While percentages move up and down in different years, they have overall remained consistent in the last decade: Post-War/Contemporary (ranging 45-50% by value), Modern (about 25-30%), Impressionist (10-12%), Old Masters (4-5%).” (p.4)

“Cultural goods overall account for no more than 0.1% of illegal activity. According to reporting by the World Customs Organization, ‘cultural property’ crimes are dwarfed by other unlawful activity. (p.5)

“There are also likely to be consequences to U.S. museums and collectors through mandatory reporting requirements of the identities of sellers and purchasers of artworks. FINCEN shares collected information with law enforcement in 90 other nations and tax authorities in 70 other nations. There is concern that information on legitimate U.S. sales to both museums and private persons will go to foreign governments aggressively making repatriation claims for art and artifacts traded in good faith for decades in the US and Europe.” (p.6-7)

“According to a 2020 report by the Rand Corporation (“Tracking and Disrupting the Illicit Antiquities Trade with Open Source Data”), global annual sales of Greek, Roman, and Egyptian antiquities by major auction houses totaled approximately $41 million in 2015. An estimated 2,000 to 3,000 pieces totaling between $30 million and $68 million sell at major auction houses each year. (Rand, p. 71-72.) While extraordinary pieces can command prices as high as $10 million, individual antiquities on average sell for $21,300 apiece. (Rand, p. 72.) This wide value spectrum and the average sale price is generally consistent with Christie’s own experience. As an example, our most recent Antiquities sale held in New York on October 12, 2021 featured more than 130 lots, of which more than 50 lots sold for $10,000 or less. Only 12 lots sold for more than $100,000, and one lot sold for $4.8 million.” (p.3)

Salvator Rosa: Allegory of Fortune, circa 1658 – 1659, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

“Christie’s has a risk-based global AML program that includes client identification and verification, client screening (sanctions, PEP, and negative information) and ongoing transaction monitoring. Clients (buyer and sellers, including dealers and advisors), must provide KYC (e.g., a copy of a government-issued photo ID for individuals and corporate documents showing any beneficial owner with a 25% stake or more for legal entities). Beneficial owners of legal entities with a 25% stake or more must be disclosed and are asked for government-issued photo ID on a risk basis. All clients, including beneficial owners of legal entities with a 25% stake or more, are screened (sanctions, EP, and negative news).” (p.7)

“For consistency’s sake, we support a per-transaction threshold that aligns with existing standards, such as the €10,000 per-transaction threshold set by the Fifth Anti-Money Laundering Directive (5AMLD) or the $10,000 cash reporting requirement under the BSA. Taking the value of the average antiquities transaction in the Rand report, a $10,000 threshold should capture most of the market, but not impose a disproportionate burden on those operating at the very low value end of the market. Market participants will need guidance from FinCEN on how to calculate the transaction threshold (e.g., whether it includes sales tax and commissions).” (p.10)

“The lack of public information concerning the beneficial ownership [UBO] of legal entities both in the United States and in non-U.S. jurisdictions creates challenges and inefficiencies in the CDD process. This has improved in many EU jurisdictions, where beneficial ownership registers have been put in place as part of the 5AMLD in some countries, but remains challenging in jurisdictions where this is not the case.

The lack of such registers means auction houses such as Christie’s must expend significant

resources collecting corporate documents, including ultimate beneficial owner (UBO) information, directly from clients. This can be an intensely manual process and involve several rounds of client document requests until the UBO is properly documented. If there is any requirement in the proposed regulations to obtain beneficial ownership information, we would recommend that similar to the requirements for banks with legal entity customers, a market participant, such as Christie’s, should be able to rely on information provided by the person acting for the legal entity. FinCEN should consider providing a model certification form for this purpose. It also should be clear in the regulations that copies of government-issued identity documents (rather than originals) are sufficient because there will not always be face-to-face contact with clients or beneficial owners.” (p.12)

“SARs should be encouraged but not mandatory, similar to the requirements for precious metals dealers. Market participants will need extensive guidance from FinCEN on the red flags for suspicion.” (p.13)

“When the beneficial ownership database being developed by FinCEN pursuant to the Corporate Transparency Act is operational, antiquities market participants should have access to it for due diligence purposes, with the permission of the clients, to the same extent as other financial institutions.” (p.15)

Follower of Hieronymus Bosch (circa 1450 –1516), Cleansing of the Temple, between 1570 and 1600, Kelingrove Art Gallery and Museum.

“Dealers in art may also deal in antiquities and vice-versa, and often when dealing with aged or ancient art, the terms are used interchangeably. An ancient Roman statue is as much an archaeological artifact as it is an artwork, and is equally appropriate to find in the collections of an art museum as an archaeological park. Additionally, unequal regulations on art and antiquities will be incredibly burdensome and confusing for market participants who deal in both to meet; regulations must be as consistent as possible. As such, we have suggested that FinCEN consider regulating both art and antiquities as “cultural property,” and concern themselves less with the definition of ‘art’ and ‘antiquity’ and instead devote attention to the regulations that will most benefit these markets. In keeping with this, we point to the definition of “cultural property” in the UNESCO 1970 Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property, which very wisely does not try to make a differentiation between art and antiquity and considers both (among many other things) under the scope of the definition of “cultural property.”” (p.9)[2]

“It is important to include not-for-profit institutions given recent scandals that have shown that museums are at risk of unknowingly being involved in suspect transactions. There is little need to distinguish between commercial, for-profit trade and not-for-profit trade of art and antiquities. Any non-profit or non-commercial engagement in the trade of antiquities and art — for example, for a museum collection — is still engaging in the for-profit trade, unless it is purely cultural exchange. Transactions may be financial even if currency is not exchanged. Individuals may use donations to museums for tax-write offs. Indeed, the curator Jiri Frel at the Getty Museum conducted one of the largest tax fraud schemes in American museum history by working alongside antiquities trafficker Robert Hecht to arrange for Hollywood elites to donate objects in exchange for a tax-write off at an inflated value based on appraisals forged by Jiri Frel.” (p.10)[3]

[Ed. It is noteworthy that the Financial Crimes Taskforce submission includes the Antiquities Coalition together with a number of anti-money laundering compliance contractors who could benefit from expansion of regulations.]

CLOONEY FOUNDATION FOR JUSTICE

“We urge FinCEN to adopt a broad definition of the term “antiquities” in line with the current notion of “cultural property” as defined by the international legal conventions in force and accepted by the United States. Ensuring that the FinCEN’s definition aligns with the international treaty obligations of the United States as it relates to cultural heritage would strengthen the position of U.S. law enforcement and, additionally, facilitate restitution processes of antiquities seized as part of law enforcement investigation of financial crimes.” (p.17)[4]

Massachio, Detail from The Tribute Money, showing (possibly) Judas (2nd from left) and Masaccio as Thomas (right).

“FinCEN should subject antiquities dealers to the existing suspicious activity reporting (“SAR”) mechanism. Additionally, we recommend that SARs forms related to antiquities include specific antiquities information as to why an activity was flagged due to the highly specialized knowledge required for the trade in antiquities. The antiquities SARs mechanism should also promote and mandate information-sharing and coordinated efforts between U.S. and foreign law enforcement due to the international nature of the antiquities market and its related financial flows.” (p.3)

“Overall, FinCEN must be broad and stringent in the regulatory measures it proposes for the antiquities market, including no monetary thresholds, stringent due diligence requirements, disclosure of beneficial ownership information, and comprehensive SARs filings. The criminal cases pursued by U.S. authorities are likely addressing only a very small fraction of the actual violations occurring. Such regulation would provide law enforcement with information on illicit financial flows to further dismantle criminal networks currently exploiting the antiquities market.” (p.3)

“In recent years, some of the biggest cases and scandals in the antiquities market that involved money laundering and terrorism financing have been facilitated by the U.S. financial system and have reached U.S. markets.” (p.8)[5]

“Looted antiquities from conflict areas arrive in the United States (and other market countries largely in Western Europe) via complex international networks that include smugglers, dealers, intermediaries, and brokers across North Africa, the Middle East, Gulf countries, Asia, and Eastern Europe. The transit countries are essential for the process of “laundering” the antiquities (i.e., providing customs or export documentation to legitimize their subsequent sale). A number of methods are being used to avoid customs inspections and conceal the illicit nature of the artifacts, including false declaration of the value of a shipment (lower than market value); false declaration of the country of origin of a shipment (a transit rather than source country); vague and misleading descriptions of a shipment’s contents; splitting a single large object into several smaller pieces for separate deliveries, allowing informal entry and later reassembly after receipt; addressing a shipment to a third party, falsely stated to be the addressee or purchaser, for subsequent transfer to the actual purchaser; failure to complete appropriate customs paperwork; concealing antiquities in shipments of similar, legitimate commercial goods; and addressing shipments to several different addresses for receipt by a single purchaser.” (p.12)[6]

“The FinCEN regulation should broaden the scope of its protection to any “cultural objects” as defined by Article 2 of the UNIDROIT Convention . . . [C]ultural objects are those which, on religious or secular grounds, are of importance for archaeology, prehistory, history, literature, art or science and belong to one of the categories listed in the Annex to this Convention. The term “cultural artifacts” should also be included in the scope of protection of the FinCEN regulation. The term “antiquities” infers a temporal limitation that would only include objects produced during a particular period of time. While cultural artifacts potentially fall outside of this temporal scope, the trade of those artifacts can present similar incentives to armed and terrorist groups if they are perceived as a potential source of funding.” (p.20)

“The Docket recommends sanctions and/or criminal liability for failure to comply with due diligence obligations. Antiquities dealers that fail to comply with their obligations should be held liable for their failure to do so. This is common practice in a number of European countries. For example, under the French penal code, entities can be held liable for money laundering or financing of terrorism in these circumstances. Failure to comply with due diligence obligations can be sanctioned by the Direction Générale de la concurrence, consommation et répression des fraudes, the French regulatory authority that controls compliance with the obligations of diligence and declaration.” (p.26)

“We recommend a SARs mechanism for antiquities dealers that promotes coordination and sharing of information between U.S. law enforcement and foreign law enforcement. The nature of the antiquities market is that dealers in the United States have galleries, business partners, trade relationships, and attend art fairs abroad and often use these connections to hide illicit activities. U.S. law enforcement must be able to share suspicious activity information with their foreign counterparts. As part of the 2021 AML Act amendment, Congress authorized the codification of a pilot program to allow financial institutions to share SARs with their foreign branches, subsidiaries, and affiliates. We urge FinCEN to consider this pilot program in the context of antiquities dealers due to the highly international nature of the market.” (p.28-29)

CPN also recommends readers to read the submission from the Blue Shield.

[1] Section 6110(a)(1) of the AML Act amends 31 U.S.C. 5312(a)(2) to include as a type of financial institution “a person engaged in the trade of antiquities, including an advisor, consultant, or any other person who engages as a business in the solicitation or the sale of antiquities, subject to regulations prescribed by the Secretary.” Section 6110(b)(1) directs the Secretary to issue proposed rules implementing this amendment not later than 360 days after enactment of the AML Act, i.e., by December 27, 2021. This amendment to the BSA’s definition of “financial institution” takes effect on the effective date of the final rules issued by the Secretary pursuant to Section 6110(b)(1)

[2] [Ed Note: While cultural property per se has no special legal status in the U.S., the 1983 Cultural Property Implementation Act utilizes the definition incorporated under Article 1 of the 1970 UNESCO Convention but the CPIA limits both the range of property and the circumstances in which cultural property may be subject to U.S. import restrictions or seizure and return. The 1970 UNESCO Convention defines cultural property as “property which, on religious or secular grounds, is specifically designated by each State as being of importance for archaeology, prehistory, history, literature, art or science,” and lists as examples, specimens of fauna, flora, minerals and anatomy, and paleontological remains, all property related to history and individuals of “national importance,” licit and illicit archaeological discoveries, elements of artistic or historical monuments, antiquities more than one hundred years old, inscriptions, coins and seals, ethnological objects, artistic works from paintings and drawings to prints and lithographs; rare manuscripts and old books and documents; postage and revenue stamps, archives, including sound, photographic and cinematographic archives, antique furniture and musical instruments. See 19 U.S.C. §2601(5)–(6) (1983); See also Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property art. 1, Nov. 14, 1970.]

[3] [Ed Note: Jiri Frel left the Getty in 1986 under a cloud as a result of his collecting practices, recognized even 35 years ago as improper. Jiri Frel, Getty’s Former Antiquities Curator, Dies at 82, https://www.nytimes.com/2006/05/17/arts/design/17frel.html]

[4] [Ed Note: The only treaty cited by the Clooney Foundation with a broad definition of “cultural property” that was signed by the U.S. is the 1970 UNESCO Convention. Supra, note 1.The United States has not signed the 1995 UNIDROIT Convention.]

[5] [Ed. Note: The ongoing text does not actually identify any incident with a terrorist connection with trade in antiquities in the U.S. Rather, it refers repeatedly to the same half dozen crimes by individuals dating back to 2003 as establishing a criminal pattern of selling illicit antiquities, such as the gold coffin sold with false papers to the Metropolitan Museum in NY via a French auction house, and the use of trusts by Douglas Latchford to avoid inheritance tax in England. Latchford’s fortune, although he was also an antiquities dealer, came largely from his pharmaceutical manufacturing business in Thailand. There is no allegation of U.S. money laundering associated with these cases.]

[6] [Ed Note: No actual instance or case of this is cited to in the Clooney Foundation comment.]

Gaetano Gandolfi (1734–1802), Allegory of Justice, 1760s, Louvre Museum.

Gaetano Gandolfi (1734–1802), Allegory of Justice, 1760s, Louvre Museum.