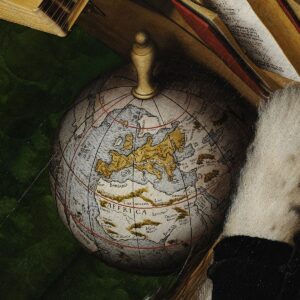

Detail of terrestrial globe in Holbein’s The Ambassadors, of a type possibly based upon a lost globe of 1523 by Johannes Schoner, from Germany.

Many cultural goods are extremely common. For example, some items like historic coins exist in the millions. Since there are insufficient resources to care for them all, private collectors are essential to their preservation. Yet, under recent administrations, State Department bureaucrats have worked hand in hand with leftward-leaning archaeological advocacy groups to promote repatriating the private property of American collectors to foreign countries that host excavations. Such confiscatory actions are promoted as “soft power measures” and as a way to combat organized crime and terrorism.

A primary tool of this crusade is increasingly overlapping import restrictions on many types of cultural goods. Even worse, a career prosecutor at the Manhattan District Attorney’s office threatens collectors across the country with criminal prosecutions unless they agree to repatriate their artifacts pursuant to foreign national patrimony laws.

With so much being reevaluated, shouldn’t there also be a reassessment of the status quo here?

Reform Import Restrictions on Cultural Goods

The 1970 UNESCO Convention contemplates that signatories will enforce each other’s export controls on cultural goods. Because many countries with authoritarian leanings lay claim to ownership of anything “old,” the US Senate only agreed to the Convention with reservations intended to preserve US “independent judgment” in such matters and to guard against retroactive application of foreign laws.

Jorge de Aguiar’s chart of the Mediterranean, Western Europe and African Coast (1492). Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Yale, New Haven, USA.

Further protections for American collectors were incorporated in implementing legislation, the Cultural Property Implementation Act, (CPIA). Over time, however, significant procedural and substantive constraints placed on executive discretion in the CPIA have devolved into a “check the box” exercise. As a result, it no longer seems to matter if there is a large, open internal market for the same cultural goods in the country in question or even that the US government recognizes the rights of authoritarian governments to the cultural heritage of displaced minority populations including Christians and Jews indigenous to the Middle East and North Africa, Tibetans and Uyghurs.

Instead, once an agreement is decided, resulting import restrictions can be applied to all types of cultural goods made or found in a particular country from ancient times to the 20th century. Even worse, overreach extends to enforcement. Import controls are not applied prospectively to items illicitly exported from a given country after the effective date of any implementing regulations, but rather far more broadly as embargoes on all cultural goods of a given type coming from legitimate markets abroad, including those in Europe. If an importer cannot prove that an artifact was on the market outside a given country as of the date of the restrictions, under current practices it is subject to detention, seizure and forfeiture.

So, what is the solution?

Map of the world with trade winds according to ye latest and most exact observations, Moll, Herman Publisher: Bowles, Thomas, 1732.

Make the preparation of any “designated lists” subject to the requirements of the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) and any enforcement actions subject to the requirements of Civil Assets Forfeiture Reform Act (CAFRA). The former would require the State Department to justify its actions in restricting common cultural goods and those of minority communities on the record. The latter would take the burden of proving a negative from importers and instead ensure that the government must demonstrate that an item was illicitly exported after the effective date of any governing regulations,

Finally, make any repatriations of cultural goods of displaced minority communities go not to their oppressor governments, but to representatives of those groups in exile.

Rein in New York City’s World Culture Cop

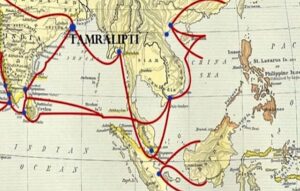

Ancient Indian maritime trade routes, by KhasEkadashTili, 5 January 2025, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

Many would be surprised to learn that a local prosecutor could threaten criminal prosecutions for violations of foreign national patrimony laws under murky New York State law. Or that he could claim broad jurisdiction based on nothing

more than an artifact, or even a transaction related to that artifact, passing through New York decades ago. Or that federal Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) would provide nationwide muscle to such threats and in doing so evade protections for targets of forfeitures enshrined under federal law.

Yet, given this threat of criminal prosecution under New York law, this team effort has been quite successful in “convincing” collectors and institutions throughout the United States (and even sometimes abroad) to agree “voluntarily” to the repatriation of cultural goods that may have been on display for decades or sold at auction multiple times over the years. Of course, most simply cave into such threats, the prospect of criminal liability and cost of litigation being just too great.

How to preserve collectors’ rights

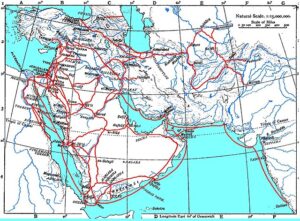

Map of trade routes in the ancient Near-East. Colour added artificially by Newman Luke. Encyclopedia Biblica, 1903.

Federalize all claims for repatriation based on foreign national patrimony laws. Give federal courts exclusive jurisdiction over such claims, make them subject to the protections of CAFRA, and place a 5-year statute of limitations on them based on when an artifact was first imported into the United States. Finally, require such claims to be brought in the federal district court where the object is located now, not New York. Due process demands it.

While some might hope that the Trump Administration’s DOGE effort may defund the entire government repatriation operation as a “woke” waste of resources, it would probably be better in the long run to try some simple, common-sense reforms first instead.

1 Peter K. Tompa is a past co-chair of the American Bar Association’s Art & Cultural Law section. He currently serves as Executive Director of the International Association of Professional Numismatists. The opinions expressed here are his own.

Previously published in the American Bar Association Section of International Law, Art & Cultural Heritage Law Newsletter, Winter 2025 issue. The Committee for Cultural Policy thanks author Peter K. Tompa and Newsletter editors Armen Vartian and Laura Tiemstra and the American Bar Association for permission to republish.

Jean de Dinteville, French Ambassador to the court of Henry VIII of England, and Georges de Selve, Bishop of Lavaur. 1533, National Gallery, London.

Jean de Dinteville, French Ambassador to the court of Henry VIII of England, and Georges de Selve, Bishop of Lavaur. 1533, National Gallery, London.