Although at present, science and religion are considered as distinct, even antagonistic modes of thought, in medieval Europe the spiritual and the empirical were closely entwined. For centuries, astronomy, the study of the stars and planets, merged seamlessly with astrology, which assigns those celestial bodies specific influence over human life. Part science, part belief system, medieval astrology existed alongside Christianity, and was a source of consolation and guidance to practicing Christians of all classes and professions. The twinned disciplines of astronomy and astrology were pursued for centuries, not only in medieval Europe, but by scholars from Portugal to Baghdad and beyond.

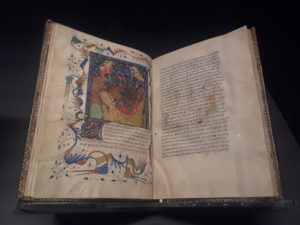

The Fall of the Rebel Angels

Avignon (probably), France about 1430

Livre de Bonnes Meurs trans: Book of Good Manners. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

Part of this complex history of scholarship and faith is explored in an exhibition at the Getty Center, The Wondrous Cosmos in Medieval Manuscripts, open until July 21st, 2019. The show draws on the Getty’s extraordinary collection of medieval manuscripts to reveal how the stars and other celestial bodies were represented in illuminated manuscripts created in Europe between the 13th and 16th centuries. The Getty’s exhibition explains the differing yet often complimentary symbolic roles played in the Middle Ages by the sun, moon, and stars in Christian religious texts, in medical and astrological texts, and in calendars.

Astrology is just one manifestation of the nigh-universal human tendency to make life meaningful by telling stories about natural phenomena. On the societal scale, and over time, this tendency gives rise to what literary theorist Northrup Frye has called the “mythological universe,” the totality of a society’s spiritual beliefs, enfolding and explaining the entire material universe. The mythological universe of medieval Europe accommodated not only Christian ideas and Biblical narratives, but also astrological beliefs, which carried with them remnants of the classical religions of ancient Greece and Rome. Through the ‘Dark Ages,’ until the classical revival called the Renaissance, the names, attributes, and histories of Classical deities were preserved in European memory in astrological texts and illuminated manuscripts.

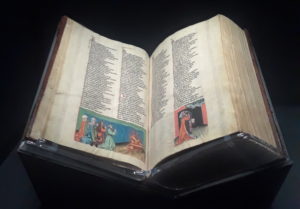

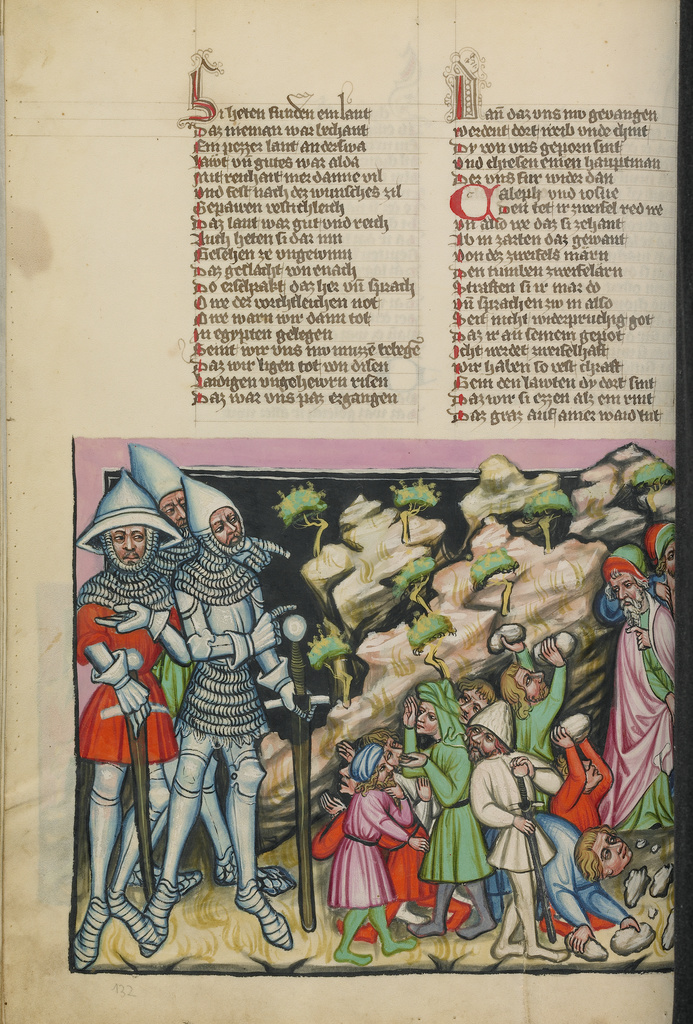

Nimrod and his companions venerating Fire: Jonicus, the First Astronomer

Regensburg, Bavaria, about 1400-1410

Rudolf von Emschronik

World Chronicle. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

The Getty’s manuscripts represent some of the most profound and intellectual labor of the Middle Ages, though some seem whimsical by today’s standards. The pages of a Miscellany text from Germany describe not the movements and appearance, but the personalities of various comets. In the middle of the left-hand page we see Veru, visualized as a fleeting rainbow on fire, “brooding like Saturn and unpredictable like Mercury.” On the opposite page Partica is described as having “the allure of Venus.” [1] Similar traits were ascribed to planets and the signs of the zodiac. As the preceding extracts suggest, although Christianity overwhelmingly dominated the religious life of medieval Europe, the complex and circular movements of stars and planets retained much of their ancient association with the older gods of ancient Greece and Rome.

Nor were these interesting studies the mere esoteric pursuits of an isolated intellectual class. Throughout history, the stars have been consulted, alongside other auguries, by prognosticators whose advice helped to dictate the course of politics. Many of the Getty’s manuscripts demonstrate the importance of astronomers or astrologists to the ruling class in managing political and personal affairs. One illuminated tome, a World Chronicle intended for King Conrad IV of Germany, shows the little known fourth son of Moses, Jonicus, who is credited as the first astronomer. The text states that Jonicus advised the Mesopotamian ruler Nimrod “by observing the position of stars and planets in the night sky… Jonicus predicted future events, including the rise and fall of competing empires.”[2]

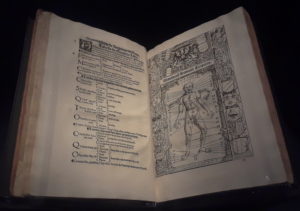

Zodiacal Man

Oppenheim 1518

Johann Stoeffler

The Great Roman Calendar. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

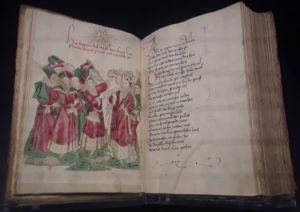

Another manuscript page, from a retelling of the story Barlaam and Josaphat, depicts a royal couple in India consulting with astrologists about the future of their son, prince Josaphat. The monarchs are displeased with the astrologers’ prediction that Josaphat will become a Christian and confine him to the palace. Despite the King’s attempts to cloister his son, Josaphat met the hermit Saint Barlaam, was exposed to poverty, old age, sickness, and death, and became a Christian, in fulfillment of the astral prophecy.

Readers familiar with Buddhism will recognize this story’s direct derivation from that of prince Siddhārtha Gautama, who became Shakyamuni Buddha, on whose teachings Buddhism was founded.[3] In the context of this exhibition, however, the tale is more notable for its emphasis on the incontrovertible power of the planets to predict the passage of events on earth.

The movement of the heavens informed much of medieval life. In a purely practical sense, the changing seasons, brought on by the movement of the Earth around the Sun, formed the basis for all the activities of the medieval agricultural laborer. The stages of the zodiac were considered equally important, for medical as well as astrological purposes. Among the most striking works demonstrating this is a Latin manuscript Astronomical and Medical Miscellany, which contains a medieval revolving calendar called a volvelle. A set of overlapping parchment disks, marked with the changing positions of sun, moon, and zodiac constellations, could be rotated to determine their particular relations on any day in the year. Used in conjunction with the lunar and zodiacal chart on the previous page, it could help to determine the causes of a sick person’s ailments, and the timing of religious observances such as Easter.[4]

“The Royal Couple with Astrologists”

Hagenau, Alsace, 1469

Follower of Hans Schilling

Barlaam and Josaphat. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

There are other manuscripts which recall just how often, in the Bible, sun, moon, and stars play an active role, as in the Star of Bethlehem, which led kings and shepherds to the Nativity of Jesus, or the “Woman clothed in the sun” of the Apocalypse. The luminous halos which surround holy figures in these manuscripts, often decorated with gold leaf, also recall the radiance of the sun and stars. These celestial elements of the Christian art appear well-represented in the Books of Hours on display. A Book of Hours was a popular devotional book containing prayers and psalms for laypeople, laid out according to the time of day and of year when they should be said. These days and times were, naturally, also determined by the movements of the sun and moon, completing the cycle of reference to and interpretation of the celestial bodies in medieval life.

The “Wondrous Cosmos” described in the Getty exhibition’s title was deeply infused with many spiritual, scientific, and metaphorical meanings. All its observers, from the farmer to the astronomer to the monk, had something to learn from watching the sky. The curious can share their experience of the heavens at the J. Paul Getty Museum until July 21st.

[1] From the museum label “Comets”, in German, shortly after 1464, Ulm, Germany; Augsburg, Germany.

[2] From the museum label “Nimrod and his companions venerating Fire: Jonicus, the First Astronomer”, Regensburg, Bavaria, about 1400-1410, by Rudolf von Ems,

World Chronicle (Text in German).

[3] From the museum label “The Royal Couple with Astrologists”, Hagenau, Alsace, 1469, By a Follower of Hans Schilling, Barlaam and Josaphat (text in German).

[4] From the museum label “Astronomical Table with Phases of the Moon”, Volvelle, Oxford, shortly after 1386, Astronomical and Medical Miscellany (text in Latin).

World Chronicle

“Rudolf von Ems, a German knight and prolific writer, composed his World Chronicle in German (Weltchronik) toward the middle of the 1200s. In rhymed couplets, the chronicle weaves biblical, classical, and other secular texts into a continuous history of the world, beginning with Creation. Its overarching theme is the revelation of God's plan of Christian salvation through the course of time. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

World Chronicle

“Rudolf von Ems, a German knight and prolific writer, composed his World Chronicle in German (Weltchronik) toward the middle of the 1200s. In rhymed couplets, the chronicle weaves biblical, classical, and other secular texts into a continuous history of the world, beginning with Creation. Its overarching theme is the revelation of God's plan of Christian salvation through the course of time. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.