Sign, American Museum of Natural History, NY, Feb. 2024.

Download PDF The New NAGPRA- ‘traditional knowledge’ in, artifacts out.

“These regulations clarify and improve upon the systematic processes for the disposition or repatriation of Native American human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, or objects of cultural patrimony. These regulations provide a step-by-step roadmap with specific timelines for museums and Federal agencies to facilitate disposition or repatriation. Throughout these systematic processes, museums and Federal agencies must defer to the Native American traditional knowledge of lineal descendants, Indian Tribes, and Native Hawaiian organizations.”

43 CFR Part 10, Department of the Interior Summary of the Final Rule revising and replacing definitions and procedures for lineal descendants, Indian Tribes, Native Hawaiian organizations, museums, and Federal agencies to implement the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990, December 13, 2023.[1]

“The artifacts in this case have been removed from view because the Museum does not have consent to display them.”

Sign at the American Museum of Natural History, NY, Feb. 2024

Precis

When Congress passed the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act in 1990, it represented a huge step forward in recognizing the rights of Native American, Alaskan, and Hawaiian communities. Congress intended NAGPRA to right many past wrongs against America’s indigenous peoples, such as the U.S. government’s 19th and early 20th centuries prohibition of Native religion and the wanton seizure of sacred artifacts and inhumane treatment of ancestral remains. NAGPRA has done much to ensure honor and respect for Native American property, cultural, and religious rights.

Thirty-four years later, many tribal entities are understandably frustrated at how long it has taken federally funded institutions to identify and return all ‘ancestors’ – the term for human remains – to the tribes. Others are motivated by a sense that Native rights have been usurped by the ownership of art and artifacts by non-Natives, and the belief that the trade in Native art, which has been very active for the last 150 years, is a form of exploitation. Some activists argue that only the return of all Native artifacts will serve as therapeutic action to heal damaged communities. Others believe that rights to ownership, control, and research on indigenous art and artifacts in both public and private hands, regardless of its history in trade, should rest entirely with current Native organizations. They argue that objects, however old and however originally acquired, should only be purchased and sold with the approval of current tribes.

Tipi bag, ca. 1890, North Dakota or South Dakota, USA: Lakota/ Teton Sioux, Charles and Valerie Diker Collection of Native American Art, Metropolitan Museum, NY. During the early reservation period, the United States government outlawed the Lakota’s annual Sundance and instituted 4th of July celebrations instead. The American flag and interpretations of the Great Seal of the United States became popular beadwork motifs at this time.

These concerns are addressed in the rewriting of the purpose of the NAGPRA regulations to give explicit recognition and deference to Native American traditional knowledge. Section 10.1(a) Purpose, of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Regulations states in paragraph 3:

“Consistent with the Act, these regulations require deference to the Native American traditional knowledge of lineal descendants, Indian Tribes, and Native Hawaiian organizations.” [2]

New regulations for NAGPRA came into force in January 2024, intended to speed the return of ancestors and artifacts to tribes and to give Native Nations’ governments greater authority in how Native heritage is managed in institutions receiving federal funding. For the most part, these are U.S. federal agencies, museums and educational institutions. However, libraries, historical societies, parks and other entities that are funded by cities or counties that receive federal funds are also specifically covered under the new rules.

The most dramatic and obvious change is that new NAGPRA regulations, in concert with the deference expressed in paragraph 3 of the Purpose above, require free, prior, and informed consent by the represented tribes before any exhibition of, access to, or research on human remains or cultural items.[3] Some museums are closing galleries and removing objects from public view until the requisite permission is obtained from tribes, restricting public access to Native American, Hawaiian, and Alaskan art and heritage nationwide.

New rules on repatriation may enable expanded claims to ancient objects and identification of objects as sacred or cultural patrimony based on tribal traditions rather than historical or scientific evidence, making some removals permanent. At the least, the requirement for prior consent to display ‘cultural items’ will require museums to obtain permission from Native American tribal governments, Native Hawaiian Organizations and Alaska Native Corporations whose cultural items are represented in their collections.[4] The new regulations also recognize direct descendants of the original owners as having a say in how objects are handled and displayed. Since there are over 550 federally registered tribes in the continental U.S. alone, obtaining permissions for even a limited number of objects may be a daunting task.

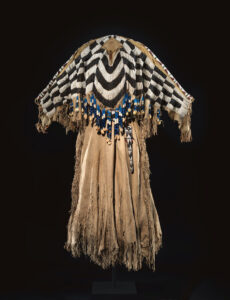

Dress and belt with awl case, ca. 1870, made in Oregon or Washington, USA, Wasco, The Charles and Valerie Diker Collection of Native American Art, Gift of Charles and Valerie Diker, 2019. Garments of superior craftsmanship incorporating trade goods, such as this example, expressed personal identity and a family’s high status. The dress is accompanied by its own belt and awl case.

The regulations do not address the possibility that a tribe and museum may disagree as to what is a cultural item subject to restrictions on display. What if a tribe does not answer a request for consent? Does the object languish forever in a storeroom? What if the tribe refuses the request? Can the museum seek a non-binding decision from the NAGPRA Committee or seek relief from a Federal Court? Is it assumed that the item for which consent is refused should be repatriated unless a museum meets the high standard for proof of a right of possession?[5] There are many unanswered questions.

While some of 2024’s regulatory changes to NAGPRA are useful and practical steps intended to streamline processes and facilitate repatriation of objects, many appear focused on “restorative justice” to the point of endangering legitimate scholarship, the preservation of the human record, and the public interest. Instead of improving the law’s administration, other changes will encourage ad hoc decision-making by tribes without public accountability.

Honest, straightforward consultation between museums and tribes is essential for the proper operation of NAGPRA and the achievement of its goal to return ancestral remains, sacred objects needed for ceremonies today, and inalienable items of cultural patrimony to tribes.

But the new rules create uncertainties that will discourage private collectors of Native American, Hawaiian and Alaskan art from donating artworks to museums for the public’s education and enjoyment, fearful that gifts will become subject to unpredictable tribal demands.

The 2024 regulations already constrain museums to meet drastically tightened schedules for return without providing funding to get the work done and requiring deference to undefined forms of ‘Native American traditional knowledge’ that need not be continuous or old, and may supersede scientific or historical evidence. The requirement for obtaining permission for display was a last-minute addition to the NAGPRA regulations, not raised for public consultation before the issuance of new rules in December 2023, that prompted museums’ withdrawal of objects from exhibition. Whether intended or not, the effect of the new regulations has been to substitute tribal demands for museums’ decision-making, even though the Department of the Interior denies that this is the case.[6]

New NAGPRA regulations: The impact on museums, educational institutions, donors and researchers.

Photograph, Interior of Indian museum showing Northwest coast Native American artifacts with group of school children gathered for lecture, Tacoma, Washington, ca. 1905. University of Washington, Albert Henry Barnes Collection.

Visitors to US science, art and natural history museums in 2024 are finding galleries closed and vitrines that once held historic and beautiful examples of Native American pottery, masks, carvings, costume, and forms of adornment shrouded – some bearing notices that say, “The artifacts in this case have been removed from view because the Museum does not have consent to display them.”

The removals and closures are museums’ response to release of new regulations implementing NAGPRA, the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. The new rules, which went into effect on January 12, 2024, not only require a wholly appropriate consultation with tribes on the care and treatment of art and artifacts in U.S. museums but include a new provision requiring explicit permission from the originating tribes for exhibition.

Native American art is the most popular and widely held form of art in the U.S. There are over 550 federally recognized tribes today – and hundreds of U.S. museums hold a wide range of contemporary, antique, and ancient objects made by Native peoples from Florida to Alaska. Many museums have built positive consultative relationships with Native American nations within their state or region or with tribes represented in their holdings. Under the new rules, this is not enough. And these are just some of the concerns museums are facing under the new regulations.

Tribal consent required before exhibition of “cultural objects.”

Lakota (Sioux), Post-Contact Beaded Child’s Vest, Date c. 1890, Cleveland Museum of Art, accessioned 1984.105, Bequest of David S. McMillan, CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain.

The unexpected addition of a requirement for museums and federal institutions to obtain consent from tribes prior to any exhibition of, access to, or research on human remains or cultural items limits access to objects in museums even more than the proposed changes originally announced by the US Department of the Interior in October 2022. Shuttered museum galleries are just the most obvious of a host of changes that may dramatically alter public and scholarly access to the American continent’s early history.

On January 26, 2024, President Sean Decatur of the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, the largest natural history museum in the world, announced that the museum would close its entire Native American exhibit halls, covering 10,000 square feet, pending determinations of compliance with the new rules. “The number of cultural objects on display in these halls is significant, and because these exhibits are also severely outdated, we have decided that rather than just covering or removing specific items, we will close the halls,” he said. The museum, which has 4.5 million visitors a year, is “rethinking” its field trips for students in light of the closures.

The Denver Museum of Art has removed a display case of ceramics, the Cleveland Museum of Art has covered three of its six cases of Native North American art, the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University will remove all funerary belongings from exhibition. The Metropolitan Museum in New York has removed objects from its musical instruments displays. The Seattle Art Museum has removed five Northwest Coast objects of Tlingit origin from its galleries, deeming them ‘cultural objects’ for which permission to display them must first be obtained and is considering removing more.

It’s no wonder that museums were surprised by the new regulations. A 2021 draft overview stated only that the new rules would require “museums and Federal agencies to exercise a duty of care prior to repatriation.” In the 2022 proposed rules, Section 10.1(d) Duty of care, required museums to “Consult, collaborate, and obtain consent on the appropriate treatment, care, or handling of human remains or cultural items,” not their exhibition and public display.

As the announcement by the Cleveland Museum pointed out, the 30-day period between announcement and the regulations taking effect was insufficient to determine who needed to be consulted, who had authority to grant permission, or the process to obtain consent.

Museum collections of Native American objects are almost entirely made up of secular objects. Most Southwest and Plains Indian collections were made from objects collected after tribes began commercial production of Native arts in the 1870s and 1880s. Commercial trade by Northwest Coast and Alaskan Native Tribes dates even earlier, to the late 18th century. Art museum collections reflect their donors’ interest in objects from the 150-200 years of legal trade in Native American art and artifacts. While items that were acknowledged as sacred and ceremonial objects were common in museum collections in the past, this is far rarer today as tribes that wanted to repatriate them have been able to claim them through NAGPRA for more than 30 years.

What is the current status of returns of human remains and associated funerary objects under NAGPRA?

Socorro black-on-white storage jar. ca. 1050–1100, Ancestral Pueblo. Charles and Valerie Diker Collection of Native American Art, Promised Gift, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY.

While the changes to NAGPRA regulations have been reported in the press as intended to speed up the repatriation of human remains and associated objects, the sudden museum closings are only tangentially related to any requirement to return objects to tribes. It’s the addition of a requirement to obtain explicit consent from each tribe to display “cultural items” that has pushed museums to take precipitate steps to remove all public access to their exhibition halls.

It’s important to note that the items being removed from exhibit were not human remains or funerary goods “looted from freshly dug graves” as one ill-informed museum curator described the situation.[7] U.S. art museums display artworks and a range of cultural objects, not Native American human remains.

Educational institutions and federal repositories hold the largest number of Native remains or partial remains; the University of California at Berkeley held the largest number of culturally unidentified remains, approximately 97,000, and the University of New Mexico one of the smallest, about 750, pending notice in 2020.

NAGPRA was enacted in 1990 primarily in order to ensure that hundreds of thousands of Native American, Alaskan and Hawaiian human remains – often referred to as ‘ancestors’ – held in research institutions and science museums were returned to their descendant tribes.

The National Park Service reported in 2020 that:

- As of Sept 2020, 116,857 human remains are pending consultation and/or notice.

- Between 1990 and 2020, 91.51% of culturally affiliated human remains – that is, remains whose tribal affiliation can be determined – have completed the NAGPRA process.

- Over 1.78 million associated funerary objects have been transferred along with human remains.

- 28% of museums subject to NAGPRA have resolved all Native American human remains under their control.

- More than 332,000 unassociated funerary objects have been repatriated.

- About 21,000 other cultural items have been repatriated.[8]

Bandoleer Bag, ca. 1870, Delaware, Metropolitan Museum, NY, Gift of Charles and Valerie Diker, 1999.

By September 2023, 86,000 human remains were culturally identified, reported under NAGPRA and their disposition was completed. 26,000 were not culturally identified but reported and completed. From 2020 to 2023, approximately 22,000 more were reported as completed. Of the 95,000 human remains whose disposition had not been completed, 90,000 have not been culturally identified. In its 2020 report, however, the National Park Service noted that NAGPRA activity was steady and that, “Cultural affiliation studies and in-depth consultations could resolve the rights to many of these individuals.”

The 2024 regulations both encourage consultation and effectively loosen the requirements for how culturally unaffiliated remains should be identified, making it possible for institutions holding them to return them to likely related tribal groups. But the rules also repurpose NAGPRA to give authority and control over potentially all Native American art and artifacts in museums and federal agencies to tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations – effectively requiring tribal permission for museum and institutional management and administration of historical collections.

The oft-repeated requirement in the rules to obtain consent from consulting parties prior to any exhibition of, access to, or research on human remains or cultural items also raises serious questions regarding scholarly and public access to information. It is not stated whether publication or other documentation of cultural objects would require tribal permission. A few tribes have called for a halt the publication of images of sacred objects; some have demanded that prior publications be censored or destroyed. Going forward, would publication of objects by museums also require tribal permission? Some museums have removed photographs of Native American objects from their online catalogs.[9] Will tribes be able to impose restrictions of museum’s republication of earlier books and catalogs?

Notes on the new regulations.

How does the Department of the Interior (DOI) define “deference” to traditional knowledge? If a tribe claims an object, is it theirs?

Basket bowl, artist: Maggie Mayo James, Washoe, 1870–1952, ca. 1910, Lake Tahoe, California/Nevada.

Loan from the Charles and Valerie Diker Collection, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY.

The DOI states that “We have not defined “deference” in these regulations. The term should be understood to have a standard, dictionary definition: “respect and esteem due a superior or an elder; also affected or ingratiating regard for another’s wishes”… The requirement for deference is not intended to remove the decision-making responsibility of a museum or Federal agency … but is intended to require that a museum or Federal agency recognize that lineal descendants, Indian Tribes, and NHOs are the primary experts on their cultural heritage.”[10]

The new rules state:

“Native American traditional knowledge means knowledge, philosophies, beliefs, traditions, skills, and practices that are developed, embedded, and often safeguarded by or confidential to individual Native Americans, Indian Tribes, or the Native Hawaiian Community. Native American traditional knowledge contextualizes relationships between and among people, the places they inhabit, and the broader world around them, covering a wide variety of information, including, but not limited to, cultural, ecological, linguistic, religious, scientific, societal, spiritual, and technical knowledge. Native American traditional knowledge may be, but is not required to be, developed, sustained, and passed through time, often forming part of a cultural or spiritual identity. Native American traditional knowledge is expert opinion.” [11]

By failing to set limits of any kind, the rules do not provide a meaningful definition of Native American traditional knowledge, while making it key to determining whether a tribe can claim an object for repatriation under NAGPRA. Such ‘traditional knowledge’ also need not have been held, as one might suppose, traditionally. It can be new or relatively newly held. “Native American traditional knowledge may be, but is not required to be, developed, sustained, and passed through time.”[12]

In order to justify this broad use, the DOI points to how ‘Native American traditional knowledge’ has been a component of numerous legal agreements having to do with lands or water rights and therefore can legitimately be used to identify cultural affiliation.

Navajo, Post-Contact, Transitional Period Rug, between circa 1890 and circa 1900, Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of J. H. Wade.

One wonders how this mandated deference can fairly be applied to Hawaiian ‘traditions.’ Hawaii has no permanent ‘tribal’ organizations or established community ownership of ‘inalienable’ property. The Native Hawaiian traditional religion was abolished for all practical purposes by King Kamehameha II in 1819. The Kingdom of Hawaii, a feudal society in which property was held by a ruling elite (ali’i), was itself overthrown by American sugar planters in 1893. Today’s more than 125 Native Hawaiian Organizations are effectively self-designated and federally recognized for 5-year periods only. They encompass a very broad range of social, spiritual, and business organizations without any consistent ‘traditional knowledge.’

For similar reasons, there is no logical entity to go to to obtain full, informed and prior consent to the management, usage or display of Hawaiian materials. Native Hawaiian Organizations are not tribes, and no one organization can speak for all Native Hawaiians. [13] The new regulation does not provide any guidance as to what the consent of Native Hawaiian organizations will look like. Is consent required from all 120 plus organizations, the majority of organizations, a few organizations or just one of them in order to meet this mandate under § 10.1 (d)?

The Act includes Hawaii’s state government’s Office of Hawaiian Affairs as a ‘‘Native Hawaiian organization,’’[14] but this state office is prevented from being made up exclusively of staff of Native Hawaiian ancestry by a U.S. Supreme Court decision. Will this preeminent Hawaiian Organization be the voice for all Native Hawaiians – and if not, who will?

What are “cultural items” subject to repatriation under NAGPRA and how are they defined?

Ceremonial Manta, dated 1863, plain weave with embroidery: cotton and wool, Cleveland Museum of Art, accessioned 1921, Pueblo, Post-Contact, Late Classic Period, Gift of J. H. Wade.

The NAGPRA definition of a “cultural item” has been redefined in part adding the words “according to the Native American traditional knowledge of a lineal descendant, Indian Tribe, or Native Hawaiian organization.”

“Cultural items means a funerary object, sacred object, or object of cultural patrimony according to the Native American traditional knowledge of a lineal descendant, Indian Tribe, or Native Hawaiian organization.”[15]

There are three criteria under NAGPRA for the repatriation of an unassociated funerary object, sacred object, and object of cultural patrimony: the establishment, as appropriate, of lineal descent or cultural affiliation to identify which tribes have a claim; the establishment of the identity of the object as a cultural item; and the presentation of evidence which, if standing alone before the introduction of evidence to the contrary, could support a finding that the museum or Federal agency did not have a right of possession to the cultural item.

In its discussions prior to passage of NAGPRA Congress explained ‘cultural affiliation’ as including anthropological and archaeological evidence – assuming an essentially historical or scientific evidentiary basis for determining who could claim otherwise unidentified remains. The DOI’s extensive commentary on research to determine cultural affiliation states that it is “appropriate that museums and Federal agencies must obtain consent from lineal descendants, Indian Tribes, or NHOs before conducting activities that might physically or spiritually harm human remains or cultural items.”[16] The 1990s statutory language in NAGPRA is interpreted by the DOI very broadly today; the 2023 comments state that “research” and “scientific study” are not required in order to determine which tribes may claim objects or human remains and that, in general, repatriation may not be delayed in order to allow scientific study. Under the new rules, ‘traditional knowledge’ may be sufficient for establishing identification, if other information is not already available in previous documentation.

The written definitions of ‘cultural patrimony” and “sacred” in the new NAGPRA regulations stay the same. The DOI acknowledges that when NAGPRA was passed, Congress made clear that not all objects could be deemed “sacred” or “cultural patrimony.”[17] However, the DOI states that it added the phrase “according to Native American traditional knowledge” into this definition in order “to ensure meaningful consideration of this information during consultation.”[18]

Cultural patrimony.

To qualify as “cultural patrimony” an object must have “ongoing historical, traditional, or cultural importance central to the Native American group or culture itself,” as opposed to “property owned by an individual Native American, and which, therefore, cannot be alienated, appropriated, or conveyed by any individual…[and which must be] considered inalienable by such Native American group at the time the object was separated from the group.”[19]

Sacred.

To qualify as a “sacred object,” the new rules state that:

“Sacred object means a specific ceremonial object needed by a traditional religious leader for present day adherents to practice traditional Native American religion, according to the Native American traditional knowledge of a lineal descendant, Indian Tribe, or Native Hawaiian organization. While many items might be imbued with sacredness in a culture, this term is specifically limited to an object needed for the observance or renewal of a Native American religious ceremony.”[20]

Hunting hat, Unangan or Alutiiq, Alaska, 1800s, Peabody Museum, Harvard University, photo by Daderot, 27 May 2017, public domain.

The DOI also commented that a specific object may be deemed to be a sacred object if, based on Native American traditional knowledge, the object was ceremonially interred as part of a traditional Native American religious practice in the past, the object was subsequently disinterred, and today, it is needed by a traditional Native American religious leader to renew the ceremonial interment of the specific object by present-day adherents.[21] Congress’ express requirement that a sacred object be needed for current ceremonial use has thus been replaced with a desire by a current tribe to rebury funerary items or destroy sacred objects no longer in ceremonial use. Under the new regulations, a tribe’s intention to bury or destroy the object now qualifies as a religious practice.

Deference to currently held ‘traditional knowledge’ may lead to unexpected results. An object that was not previously considered a sacred item of that tribe may now be repatriated based on a claim by current tribal government or IPO that it is sacred. This tribal redefining means that Congress’ original requirements that a ‘sacred object’ be one that is used in current religious practice may be met so long as a tribe now incorporates it into religious practice or deems it part of their religious practice to repatriate and rebury or destroy it.

Blackfoot. Headdress Case, late 19th century, Brooklyn Museum.

Consider the recent repatriation of a group of false-face masks to the Tonawanda Band of Seneca Indians of New York, in which the perspective held by a tribe today superseded the tribal perspective of the Native American artists who actually made the work. The situation was described by historian Rob McCoy:

“A 2010 [NAGPRA] notice of intent to repatriate seemed to run directly counter to the law’s intent, as articulated by the Senate Committee. The notice announced plans to transfer 184 “medicine faces” – False Face masks – from the Rochester (New York) Museum & Science Center to the Tonawanda Band of Seneca Indians of New York. Claimants characterized these pieces were both “sacred objects” and “objects of cultural patrimony.” This, despite the fact Senecas carved the pieces specifically for public exhibition between 1935-1941 while working with the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration.”[22]

The new rules will make is easier for unrelated current tribes to claim artifacts from long extinct prehistoric tribal organizations who lived in the same regions. The provision would enable current tribes to claim objects like ancient Mimbres pots and artifacts and bury or destroy them if that reburial or destruction now becomes part of their religious practice.

In recent years. the NAGPRA committee has lowered the bar for the inclusion of objects in the ‘sacred’ and ‘cultural patrimony’ categories in repatriation claims and increasingly, subsumed the two categories in NAGPRA notices and reports. It is not uncommon now to see a claims for an object as both “sacred” and “cultural patrimony.”

Funerary object.

Chaco Culture National Historical Park, photo National Park Service, a center of Puebloan culture between AD 850-1250. The Chacoan sites are part of the homeland of Pueblo Indian peoples of NM, the Hopi and the Navajo Nation. Wikimedia Commons.

A funerary object is an object “…reasonably believed to have been placed intentionally with or near human remains. A funerary object is any object connected, either at the time of death or later, to a [death rite or ceremony of a] Native American culture according to the Native American traditional knowledge of a lineal descendant, Indian Tribe, or Native Hawaiian organization.” The term funerary object does not include any object returned or distributed to living persons according to traditional custom after a death rite or ceremony. Funerary objects are either associated funerary objects or unassociated funerary objects.[23]

The definitions of associated and unassociated funerary objects have been sources of long-standing confusion and the DOI attempted to clarify this in the 2022 Proposed Rule, stating that “…determining if the funerary object is associated or unassociated does not require identifying the specific individual with which the object was placed, but rather, only requires identifying the location of the related human remains.” [24]

The DOI Commentary issued with the final rule states:

“If the location of the related human remains is unknown, the funerary object meets the definition of unassociated funerary object. If cultural affiliation of the unassociated funerary object is reasonably identified by the geographical location where the unassociated funerary object was removed, the unassociated funerary object may satisfy the criteria for repatriation, provided the museum or Federal agency cannot prove it has a right of possession to the unassociated funerary object.”[25]

Museums and institutions “duty of care” is key to new interpretations of NAGPRA.

Section 10.1(d)(1) requires museums and Federal agencies to consult with tribes on the appropriate storage, treatment, or handling of human remains or cultural items. (This is reiterated throughout, including in revisions to §§10.4, 10.9, and 10.10.)

Section 10.1(d)(2) requires museums and Federal agencies to make a reasonable and good-faith effort to incorporate and accommodate requests made by consulting parties (see Comment 14).

Section 10.1(d)(3) requires museums and Federal agencies to obtain consent from consulting parties prior to any exhibition of, access to, or research on human remains or cultural items (see Comment 15-17).

The DOI interprets “full knowledge and consent” considering the history of Indian country and recognizes that “full knowledge and consent” does not include “consent” given under duress or because of bribery, blackmail, fraud, misrepresentation, or duplicity on the part of the recipient.

“Possession or control” and “custody.” Are privately owned objects loaned to museums subject to NAGPRA repatriation, treatment of the object, or constraints on exhibition?

The DOI commentary states that “possession or control” is a jurisdictional requirement for human remains or cultural items subject to the regulations and for repatriation.[26] Whether a museum or Federal agency has a sufficient interest in an object or item to establish “possession or control” is a legal determination that must be made on a case-by-case basis.

Cradleboard ca. 1890, Possibly made in Colorado or Utah, USA.

Ute, Charles and Valerie Diker Collection, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY.

It appears that as before, objects loaned by private owners to museums will not be subject to NAGPRA repatriation. The DOI Commentary states that having possession or control means a museum or Federal agency has an interest in human remains or cultural items, or, in other words, it may make determinations about human remains or cultural items without having to request permission from some other entity or person. This interest is present regardless of the physical location of the human remains or cultural items. A museum may have physical possession of a loaned item but legal possession and control over where the object is kept and how exhibited is based on the loan agreement, a contract agreed to by both the owner and the museum. To illustrate this concept, the DOI commentary notes that a person has the same interest in property that is in the person’s home as in property that same person keeps in an offsite storage unit. The person can make determinations about the property in the storage unit without having to request permission from the storage facility.

For practical purposes, it would be advisable for future loan agreements to make clear the scope of the museum’s responsibility and duty of care with respect to loaned objects. Loan agreements should also address a museum’s exhibition and management policies in light of these NAGPRA regulations. Many museums already consult with tribes regarding these issues, and consultation with tribes about loaned objects is common as a matter of museum ethics and policy. However, lenders may not have been apprised of changing practices in the handling and management of objects. If there are changes in museum practice under the new regulations, it seems appropriate that museums should memorialize these within loan agreements as well.

How are federal and tribal lands defined?

The questions of when and where an object in circulation today originated or was found – Whether an object was found on Indian or federally-owned or controlled land can determine if it is legally owned under both NAGPRA and the Archaeological Resources Protection Act of 1979.

Swift Dog Strikes an Enemy, Author Swift Dog Hunkpapa Lakota/ Teton Sioux, 1845–1925, ca. 1880, Made in Standing Rock Reservation, North Dakota, Charles and Valerie Diker Collection, Metropolitan Museum. In the 1860s, Plains men began to render their personal histories and those of their people on sheets of paper and in ledger books that were captured from the military or obtained in trade.

For purposes of NAGPRA:

Tribal lands means: (1) All lands that are within the exterior boundaries of any Indian reservation; (2) All lands that are dependent Indian communities; and (3) All lands administered by the Department of Hawaiian Home Lands (DHHL) under the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act of 1920 (HHCA, 42 Stat. 108) and Section 4 of the Act to Provide for the Admission of the State of Hawaii into the Union (73 Stat. 4), including ‘‘available lands’’ and ‘‘Hawaiian home lands.’’[27]

Tribal trust land outside the exterior boundaries of a formal reservation would be considered an “informal reservation,” still qualifying as Tribal land for purposes of NAGPRA.[28]

“Federal lands means any lands other than Tribal lands that are controlled or owned by the United States Government. For purposes of this definition, control refers to lands not owned by the United States Government, but in which the United States Government has a sufficient legal interest to permit it to apply these regulations without abrogating a person’s existing legal rights. Federal lands include:

Any lands selected by, but not yet conveyed to, an Alaska Native Corporation organized under the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (43 U.S.C. 1601 et seq.);

Any lands other than Tribal lands that are held by the United States Government in trust for an individual Indian or lands owned by an individual Indian and subject to a restriction on alienation by the United States Government; and

Any lands subject to a statutory restriction, lease, easement, agreement, or similar arrangement containing terms that grant to the United States Government indicia of control over those lands.”[29]

Hopi Pueblo (Native American). Kachina Doll (Paiakyamu), late 19th century. Museum Expedition 1904, Photo: Brooklyn Museum.

The DOI Commentary states that because many different agencies and authorities can establish federally controlled lands, the determination of whether the land on which objects are found qualify as federally controlled will be made on a case-by-case basis. In some circumstances, the definition may include lands leased by the Federal agency, depending on the nature of that lease, the Federal agency’s statutory authority, and other circumstances. The DOI states that it cannot instruct Federal agencies on their own circumstances or statutory authorities, and recommends Federal agencies consult with their legal counsel in making such determinations.

This does not address the status of an object that is known to have been found on private land that has at one time or another been leased to a federal agency but the date of finding is unknown.

A DOI commentary states that “when a museum with custody of human remains or cultural items cannot identify any person, institution, State or local government agency, or Federal agency with possession or control, the museum should presume it has possession or control of the human remains or cultural items for purposes of repatriation under the Act and these regulations.” Likewise, if a Federal agency that can’t identify the type of land where an object was found or whether an item came to it before or after November 16, 1990, should it presume that a museum had ‘control’ for purpose of repatriation?[30] Instead of adopting a proposed “geographical affiliation” means of determining cultural affiliation, the final rules effectively make geographical proximity, without any definition of how close current tribal lands are to findspots sufficient for cultural affiliation, if that is all the information available. [31]

Receiving federal funds? A tricky question.

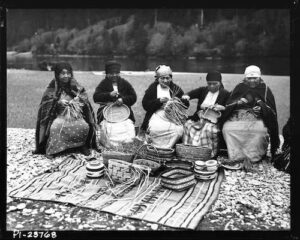

Native American women making baskets on a beach, probably on Washington’s Olympic Peninsula. Possibly at Tahola, on the Quinault Reservation, February 1926. The women from coastal Washington’s native tribes made twined, coiled and plaited baskets for gathering clams and berries, storing and serving food and many other purposes. By the 1920s, many were made for the tourist trade. Photo Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

According to the new NAGPRA rules, “receives Federal funds” means an institution or State or local government agency (including an institution of higher learning) “directly or indirectly receives Federal financial assistance after November 16, 1990, including any grant; cooperative agreement; loan; contract; use of Federal facilities, property, or services; or other arrangement involving the transfer of anything of value for a public purpose authorized by a law of the United States Government.”

This term includes Federal financial assistance provided for any purpose to a larger entity of which the institution or agency is a part. Except for procurement of property or services for the direct use of the United States Government or Federal payments that are compensatory, if the State or local government or private university receives Federal financial assistance for any purpose, then the institution or agency receives Federal funds for the purpose of these regulations.

An example of an institution receiving federal funds in the 2022 proposed regulations was of a school that received federal funds through a Pell Grant to a needy student to subsidize their tuition.

Expanding the definition of a federally-funded institution could make thousands of unsuspecting schools, libraries, and other public service institutions subject to NAGPRA reporting requirements.

This interpretation could significantly broaden the number and type of institutions required to inventory, send notices to tribes, and potentially repatriate objects– now solely under a claim based on ‘traditional knowledge.’

Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture Tour, Author Seattle City Council, 9 January 2017, CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

A curious example of the perils of the federal funding provision occurred in 2018 involving objects donated in 1880 to the Medford Public Library by James G. Swan, a Medford resident who served as a U.S. Indian agent and ethnographer in Washington State and who also collected objects for the Smithsonian. The library had located the objects by accident after they’d been stored for more than 100 years and intended to sell them to help fund building a new library. Under the assumption (absent any evidence) that the objects had been purchased under duress, the library, which receives funding from the City of Medford, which receives federal funding for unrelated projects, was told that not only was it in violation of NAGPRA for not inventorying the objects, but received widespread press coverage alleging, incorrectly, that the items were “stolen” and that an institution receiving federal funding “must return Native American artifacts to tribes,” a gross distortion of NAGPRA regulations.[32]

Among the DOI’s comments regarding federal funding issues is the statement that, “Regarding the nature of funds received through specific Federal programs, a case-by-case determination as to the nature of such funds is outside the scope of this regulatory action. We recommend seeking technical assistance from the National NAGPRA Program on specific Federal programs.”[33]

What is a right of possession and how will that be applied to museum collections?

Acomita polychrome water jar, ca. 1790, Acoma Pueblo. Charles and Valerie Diker Collection, Metropolitan Museum, NY, 2018.

Right of possession means possession or control obtained with the voluntary consent of a person or group that had authority to alienate the object. When a repatriation request is made, the request “must include information to support a finding that the museum or Federal agency does not have right of possession to the unassociated funerary object, sacred object, or object of cultural patrimony. The museum or Federal agency has an opportunity to respond by proving that it has a “right of possession.”

Right of possession is given through the original acquisition of:

(1) An unassociated funerary object, a sacred object, or an object of cultural patrimony from an Indian Tribe or Native Hawaiian organization with the voluntary consent of a person or group with authority to alienate the object; or

(2) Human remains or associated funerary objects which were exhumed, removed, or otherwise obtained with full knowledge and consent of the next of kin or, when no next of kin is ascertainable, the official governing body of the appropriate Indian Tribe or Native Hawaiian organization.

The DOI states that it is unlikely that a museum or federal agency will have a right of possession to an object of cultural patrimony, given the definition of that term.[34] It notes that to establish possession or control is a legal determination that must be made on a case-by-case basis.

According to the DOI Commentary, a museum should presume it has possession or control of the human remains or cultural items for purposes of repatriation when it cannot identify another holder with superior title. When a federal agency cannot determine if human remains or cultural items came into its possession or control before or after November 16, 1990, or cannot identify the type of land the human remains or cultural items were removed from, the Federal agency should presume it has possession or control of the human remains or cultural items for purposes of repatriation.

The DOI notes that, “when human remains and associated funerary objects are excavated from State or private land, requirements under State law may not equate to right of possession.” A museum should ensure it can prove it has a right of possession to human remains and associated funerary objects independent of State requirements.

Rachel Sahmie Nampeyo (Hopi Pueblo, Native American, born 1956). Jar, late 20th century. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Joan and Sanford Krotenberg, Photo: Brooklyn Museum.

Critics of this position have raised the issue that repatriation under these circumstances may be circumscribed by the Takings Clause in the U.S. Constitution. As an example, one commentator suggests that “if a museum has a Mimbres bowl in its collection that was excavated in 1914 on private property with the consent of the property owner, although it lacks a “right of possession” as defined by NAGPRA because it was acquired without the consent of the original owner or tribe, forcing a repatriation of the bowl would result in a 5th Amendment taking of property as the museum has good and lawful title to the bowl under State law. Mandating the removal of a museum’s collection pending required third party consent may well constitute an unlawful taking or partial taking.” [35]

A public comment submitted to the NAGPRA Committee objecting to this rule noted that this change to the existing regulations ‘‘. . . is being made without a formal review of its Fifth Amendment takings implications under Executive Order 12630’’ and will ‘‘create an opportunity for lawsuits to overturn these rules.”[36]

The subjects of Executive Order 12630 are “Federal regulations, proposed Federal regulations, proposed Federal legislation, comments on proposed Federal legislation, or other Federal policy statements that, if implemented or enacted, could effect a taking, such as rules and regulations that propose or implement licensing, permitting, or other condition requirements or limitations on private property use, or that require dedications or exactions from owners of private property.”[37]

Executive Order 12630 states that:

“Executive departments and agencies shall, to the extent permitted by law, identify the takings implications of proposed regulatory actions and address the merits of those actions in light of the identified takings implications, if any, in all required submissions made to the Office of Management and Budget. Significant takings implications should also be identified and discussed in notices of proposed rule-making and messages transmitting legislative proposals to the Congress, stating the departments’ and agencies’ conclusions on the takings issues.”[38]

The administrative burden on museums and other institutions with Native American collections.

Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture Tour, Author Seattle City Council, 9 January 2017, CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

The proposed regulations appear likely to expand the administrative, staffing, and particularly the financial burden already imposed on museums and Federal agencies. Unfortunately, virtually all museums have limited resources for accomplishing this task. Tribes also lack funding needed to work with museums. Even prior to issuance of the new rules requiring permission from tribes prior to display or exhibition, Indian tribes also submitted serious concerns about their ability to respond to requests for consultation – and the consultation requirement has just expanded a hundredfold due to the requirement for permission to exhibit.

The DOI Commentary includes numerous aspects of collections management by federal agencies and museums in responding to new discoveries (for agencies) and inventory, summaries, notices, etc. for both. Estimations by various agencies and museums and other public institutions of the likely costs and time requirement of compliance with the new regulations differed widely. Rather than attempt to summarize five full pages of the Federal Register, we refer readers to the linked notice, 43 CFR Part 10, Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act Systematic Processes for Disposition or Repatriation of Native American Human Remains, Funerary Objects, Sacred Objects, and Objects of Cultural Patrimony, Vol. 88, No. 238, December 13, 2023.[39]

What is the schedule for compliance?

Under NAGPRA, a museum or Federal agency must compile a summary of cultural items and an itemized list of human remains and associated funerary objects in its possession or control.[40] The schedules for completion of summaries, lists and inventories, for reporting on collections held in museums, and for responding to requests for repatriation, and for notice are detailed and timelines vary from 14 days to five years. Detailed instructions for the repatriation process may be found under §10.10.[41]

Lakota canvas tipi, circa 1900, Smithsonian National Museum of the Native American, photo 2012, photo by Tim Evanson from Cleveland Heights, Ohio, CCA-SA 2.0 Generic license.

The new NAGPRA rules extend the timeline proposed under the 2022 proposed rules “to allow five years (rather than two as proposed) for museums and Federal agencies to consult and update inventories of human remains and associated funerary objects.”[42] These timelines may be very challenging for institutions to meet, as almost all of the human remains they still hold are classified as unidentified as to cultural affiliation. Tribes are no longer required to submit a written request for consultation, but consultation is of course required. The new regulations express a firm intention to hold institutions to these deadlines.

A speeded-up schedule for repatriation of human remains would certainly be a positive achievement for both holding institutions and tribes. However, requirements to accelerate completion of NAGPRA inventories and notice, at the same time as consulting with tribes to update which objects they deem sacred or cultural patrimony, plus the requirement to obtain permission for display of ‘cultural items’ – the timely completion of all these tasks will be extremely burdensome for institutions and museums that hold objects from many different tribes.

CCP spoke to an administrator at a smaller museum with holdings of both local and regional Native American art and donated artifacts from many different tribes across the country. She said that despite already having a local tribe in a permanent consultative role, the institution’s only curator for Native American objects would probably have to spend the next three years doing nothing but NAGPRA work – instead of planning educational programming for local schoolchildren and the public.

Unintended consequence: Museum collections not previously considered cultural patrimony, sacred or funerary objects may be redefined – even non-Indian “human remains.”

It appears that exhibition of human-related items from other cultures not previously considered sacred or funerary objects may also be redefined as a result of the changes to NAGPRA. One museum, apparently overreacting to rules imposed on Native American objects and the purported ‘sensitivity’ that all must show to human remains, is removing Tibetan objects such as ornaments with ‘human bone’ beads (most of which are yak bone anyway), along with religious paraphernalia such as skull drums that any Tibetan would view as ordinary and respectful usage of human remains. What museums will do in the future with African statuary that frequently incorporates human hair and bits of bone is another matter. These objects are bought, sold, and displayed in museums around the world including in Africa, and in India and Nepal, now the home of many Tibetan exiles.

A closing example.

The DOI Commentary contains just a few examples of determinations made on potential NAGPRA claims. The following example is illuminating in regard to NAGPRA decision-making:

Oval lidded birchbark box decorated with porcupine quillwork, made for sale; Mi’kmaq, second half of 19th c., Missouri History Museum

“[A] museum has information that a pipe was acquired and accessioned in 1985 from an individual donor, a doctor, who originally received the pipe in 1965 as a gift. During consultation, a traditional religious leader identified the pipe as a sacred object needed by present-day pipe carriers for a traditional pipe ceremony. By speaking with elders, the traditional religious leader learned that in 1954, the U.S. Government terminated the Indian Tribe of the last Native American to own the pipe. Termination resulted in the Tribe’s land base being sold, relocation of the Tribe’s people to multiple urban areas throughout the U.S., and the forced suspension of the traditional religious practice associated with the pipe. The Native American owner relocated to the metropolitan area of the museum in 1957 and was unemployed from 1963 until the end of his life in 1966. The terminated Indian Tribe and the Indian Tribe who identified the traditional religious leader have a relationship of shared group identity through their origin stories, inter-marriage, and pipe ceremonies. The historical context surrounding the acquisition of the sacred object by the museum would be evidence to support a finding that, while the Native American owner had the authority to alienate the pipe, this transaction was not made voluntarily or fully freely. Consequently, in making its request for repatriation of this sacred object, the Indian Tribe could state 1) the pipe is a sacred object, 2) the Indian Tribe has cultural affiliation to the pipe based on historical information, kinship, and expert opinion, and 3) the historical information surrounding the acquisition of the sacred object shows that the museum does not have a right of possession to the sacred object.”[43]

Here, the implied involuntary acquisition of the sacred object from an unrecognized tribe is what shows the DOI that the museum does not have a right of possession to the sacred object under NAGPRA.

Do the changes overstep the law? Are the changes in line with Congress’ intent in passing NAGPRA?

Many of the changes to NAGPRA represent a reversal rather than a strengthening of Congressional intent in passing NAGPRA. The new rules raise constitutional questions of takings by government without compensation and the future of museum loans that must be the subject of another article. One thing is clear – the changes have resulted in the summary closure of museum galleries, loss of access to research and limiting of future scientific study to all Americans, including Native Americans, who seek to understand the remarkable diversity of Native cultures and their impact on the continent for thousands of years.

NOTES:

[1] 43 CFR Part 10, Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act Systematic Processes for Disposition or

Repatriation of Native American Human Remains, Funerary Objects, Sacred Objects, and Objects of Cultural Patrimony, Final Rule, Federal Register, Vol. 88, No. 238, Wednesday, December 13, 2023, at 86452, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2023-12-13/pdf/2023-27040.pdf

[2] Id. at 86518.

[3] Supra, n. 1, at 86519, § 10.1(d) Duty of Care

[4] The National NAGPRA Program maintains contact information on its website at https:// grantsdev.cr.nps.gov/NagpraPublic/Home/Contact. Indian Tribes, NHOs, Federal agencies, and museums provide contact information on a regular basis according to National NAGPRA. The Advisory Council on Historic

Preservation keeps an updated list of Federal Preservation Officers for each Federal agency at

https://www.achp.gov/protecting-historicproperties/ fpo-list. The Bureau of Indian Affairs maintain contact information on Tribal Historic Preservation Offices at https:// grantsdev.cr.nps.gov/THPO_Review/index.cfm and Tribal Leaders at https://www.bia.gov/bia/ois/tribal-leaders-directory/.

[5] For explanation of the right of possession, see Supra, n. 1, at 86531.

[6] Supra, n. 1, at 86459-86460.

[7] Margo Vansynghel, Seattle Art Museum removes Native objects amid new Federal rules, Seattle Times, Fe. 2, 2024, https://www.seattletimes.com/entertainment/visual-arts/seattle-art-museum-removes-native-objects-amid-new-federal-rules/

[8] National Park Service, FY 2020 Annual Program Report, https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/Reference/Profile/2285321.

[9] To give one example, the Detroit Institute of Arts has removed photographs of non-contemporary Great Lakes Native American Collections, including Chippewa, Otoe-Missouria, Ottowa, Osage and Ojibwa materials from its online catalog of the collections “out of respect”. https://dia.org/collection

[10] Supra, n. 1, at 86467.

[11] Supra, n. 1, at 86521.

[12] Id.

[13] Office of Native Hawaiian Relations/Department of the Interior, Native Hawaiian Organization Notification List, September 27, 2023, https://www.doi.gov/media/document/nhol-complete-list-pdf

[14] Supra, n. 1, at 86477.

[15] Supra, n. 1, at 86520.

[16] Supra, n. 1, at 86465

[17] From the 1990 Congressional Record: “The term sacred object is an object that was devoted to a traditional religious ceremony or ritual when possessed by a Native American and which has religious significance or function in the continued observance or renewal of such ceremony. The Committee intends that a sacred object must not only have been used in a Native American religious ceremony but that the object must also have religious significance. The Committee recognizes that an object such as an altar candle may have a secular function and still be employed in a religious ceremony. The substitute amendment requires that the primary purpose of the object is that the object must be used in a Native American religious ceremony in order to fall within the protections afforded by the bill.” NAGPRA Senate Report 101-473 (1990): 7

[18] Supra, n. 1, at 86460.

[19] Supra, n.1, at 86477.

[20] Supra, n.1, at 86521.

[21] Supra, n.1, at 86521

[22] Ron McCoy, “Is NAGPRA Irretrievably Broken?”, Cultural Property News, December 19, 2018, https://culturalpropertynews.org/is-nagpra-irretrievably-broken/ As McCoy notes:” “The museum’s Indian Arts Project was the creation of Arthur C. Parker, the institution’s part-Seneca director. Between 1935 and 1941, 31 Tonawanda Seneca men and women – joined the first year by 39 residents of the Senecas’ reservation at Cattaraugus – received fifty-cents an hour while creating 6,000 “wood carvings, beaded outfits, silver jewelry and other accessories, baskets, cornhusk dolls, and bottles, as well as more than 200 easel paintings illustrating ceremonies, traditional stories, historic events and daily activities of the people of the Reservation. They saw themselves as renewers and reclaimers of Seneca traditions and values….Parker hoped that the Indian Arts Project would nurture craftswork that could help the participants continue to earn a living. Only a few, however, continued with painting or carving that could be sold to collectors. Their work remains one of the best documented collections of Seneca materials in the world.” “The Indian Arts Project (1935-1941),” Rochester Museum & Sciences Center (n.d.: Rochester, NY), http://www3.rmsc.org/museum/exhibits/online/lhm/IAPmain.htm. One of the participants was famed author, mask carver and Cattaraugus native Jesse Cornplanter [1889-1957], who “provided designs and models for false face masks that the other carvers followed

[23] Associated funerary object means any funerary object related to human remains that were removed and the location of the human remains is known. Any object made exclusively for burial purposes or to contain human remains is always an associated funerary object regardless of the physical location or existence of any related human remains. Associated funerary object means any funerary object related to human remains that were removed and the location of the human remains is known. Any object made exclusively for burial purposes or to contain human remains is always an associated funerary object regardless of the physical location or existence of any related human remains”. Supra, n. 1 at 86520. “If the location of the related human remains is unknown, the funerary object meets the definition of unassociated funerary object. If cultural affiliation of the unassociated funerary object is reasonably identified by the geographical location where the unassociated funerary object was removed, the unassociated funerary object may satisfy the criteria for repatriation, provided the museum or Federal agency cannot prove it has a right of possession to the unassociated funerary object.” Supra, n. 1 at 86473.

[24] Supra, n.1, at 86471.

[25] Supra, n.1, at 86473.

[26] Supra, n.1, at 86453.

[27] Supra, n.1, at 86482.

[28] Id. See also Oklahoma Tax Comm’n v. Citizen Band Potawatomi Indian Tribe of Oklahoma, 498 U.S. 505, 511 (1991).

[29] Supra, n.1, at 86520.

[30] Supra, n.1, at 86520.

[31] Supra, n.1, at 86521.

[32] Natalie Guevara, Native Artifacts from PNW to go into storage after auction is cancelled. Seattle Post Intelligencer, November 21, 2018, https://www.seattlepi.com/seattlenews/article/PNW-Native-artifacts-auction-cancelled-Medford-13409799.php.

[33] Supra, n.1, at 86480.

[34] Supra, n.1, at 86502.

[35] William Hughes, Esq. Personal communication to the Committee for Cultural Policy, Inc. February 2, 2024.

[36] Supra, n.1, at 86505.

[37] Executive Order 12630 of Mar. 15, 1988, https://www.archives.gov/federal-register/codification/executive-order/12630.html, see also 53 FR 8859, 3 CFR, 1988 Comp., p. 554.

[38] Id.

[39] Supra, n.1, from 86509 to 86513.

[40] 25 U.S.C. 3003(a) and 3004(a).

[41] Supra, n.1, at 86532-86537

[42] Supra, n.1, § 10.10(d) Chart, Deadlines for completing an Inventory, at 86534

[43] Supra, n. 1, at 86502.

Native American gallery, American Museum of Natural History, c 1900-1918.

Native American gallery, American Museum of Natural History, c 1900-1918.