Τον κόρον υπό του πλούτου γεννάσθαι, την δε ύβριν υπό του κόρου.

Satiety comes of riches and hubris comes of satiety. Solon (630-560 BCE)

At times it seems that older gods have it in for Washington, DC’s Museum of the Bible, built and supported by craft-store billionaire Steve Green. The museum has been dogged by scandal since its opening in 2017. Some, though not all, of its vicissitudes bear the marks of hubris.

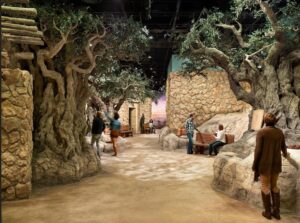

Museum of the Bible, Inside the World Of Jesus of Nazareth exhibition. Courtesy MOTB.

On January 27, 2021, the museum returned over thirteen thousand objects with “insufficient reliable provenance” to Egypt and Iraq. The objects appear to have been collected by Green and Hobby Lobby in the decade prior to the museum’s opening in 2017. The repatriated objects include a collection of 8,168 clay objects of Iraqi origin and approximately 5,000 papyri fragments and other items returned to the Arab Republic of Egypt. The Egyptian objects were returned to Cairo and the Iraqi objects to Baghdad by representatives of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

Shaaban Abdul Jawad, head of the retrieved antiquities department told Gulf News that all of the Egyptian-origin objects in the Museum of the Bible’s possession were being returned to Egypt. They include manuscripts and fragmentary texts, funerary masks and decorated coffin elements. The museum and Egyptian authorities are said to have been in negotiation for the return since 2016. Other Egyptian government officials have said explicitly that all had come from illegal excavations, not from the country’s museums or museum storehouses. Egyptian officials announced that the returned objects would be placed in Cairo’s Coptic Museum.

In conjunction with the transfer, Board Chairman Green announced that title to the Iraqi objects had been transferred to its government in May 2020 and title to the 5,000 Egyptian items to the Government of Egypt a few days later. Having learned that another 3,800 objects turned over to the Iraqi Embassy in Washington in 2018 were still there, awaiting shipment, the MOTB assisted in shipping these back to Iraq at the same time.

Iraqi cuneiform tablets

The objects still sitting at the Iraqi embassy appear to be those seized by U.S. Customs from a shipment labeled as “handcrafted clay tiles” that was sent to Hobby Lobby in 2011. Asserting that it was unaware of U.S. laws prohibiting their importation, Hobby Lobby settled in 2017, paying a three million dollar fine and agreeing to return the artifacts to Iraq. Following the settlement, the Museum of the Bible stated, “We have been made aware of the settlement between Hobby Lobby and the government. The Museum of the Bible was not a party to either the investigation or the settlement. None of the artifacts identified in the settlement are part of the Museum’s collection, nor have they ever been.”

Subsequent to Hobby Lobby’s prosecution by U.S. authorities in the Iraq matter, the Museum of the Bible has undertaken a number of internal reforms and investigations of its collections to determine whether past acquisitions by Hobby Lobby donated by the Green family were licit or not.

‘Dead Sea scroll’ fragments

The Greens have had poor luck with other acquisitions. Among the most well-publicized assets gifted to the museum were sixteen fragments of parchment identified as pieces of Dead Sea scrolls, the earliest renditions of texts of the Hebrew bible. These had been purchased over time from collectors around the world, but some could be traced back to sales by a Bethlehem antiquities trader, Khalil Iskander Shahin, aka Kando in the 1950s. Although at first only a few were known, at least 80 more fragments located around the world were identified as coming from Kando’s family after 2002.

Museum of the Bible, Drive-thru History exhibition. Courtesy MOTB.

The Museum of the Bible’s opening exhibition in 2017 included a display of these ‘Dead Sea scroll’ fragments. However, a number of biblical scholars questioned their authenticity and the museum sent the fragments for testing, first by the Federal Institute for Materials Research in Germany and then by Art Fraud Insights. The analysis by Art Fraud Insights found, among other discrepancies, that although the leather base for the writings was very likely ancient, the ink had been applied on top of the encrustations of age rather than being found under it. In March of 2020, the MOTB formally announced at an academic conference held at the museum that all sixteen of the museum’s fragments were forgeries.

MOTB CEO Harry Hargrave said to National Geographic, “We’re victims—we’re victims of misrepresentation, we’re victims of fraud.”

The museum made the best of a bad situation, using the discovery that the Greens, together with a dozen other collectors, had been tricked as a springboard for research into the purported ancient texts. Jeffrey Kloha, a chief curator, told National Geographic, “We really hope this is helpful to other institutions and researchers, because we think this provides a good foundation for looking at other pieces, even if it raises other questions.”

Papyrus Biblical Texts

The Museum of the Bible was recently caught up in – and helped to uncover – a theft of ancient Egyptian papyri from an Oxford institution. Professor Dirk Obbink, a world-famous biblical scholar currently at Oxford University in England, has been accused of taking ancient

Museum of the Bible, King James Bible exhibition. Courtesy MOTB.

papyrus texts from the collection of the Egypt Exploration Society (EES). In June 2019, the EES issued a release identifying links between EES materials and a “copy of a contract of 17 January 2013 between Dr Dirk Obbink and Hobby Lobby Stores for the sale, for future delivery, of 6 items to Hobby Lobby Stores, including, according to the appended list, one parchment fragment of Matthew and one papyrus fragment each of Mark, Luke and John, all dated by the seller to circa AD 100.”

The EES is the institutional home of Oxford’s Oxyrhynchus Papyri Project, which was overseen by Dr. Obbink. Thousands of fragments of biblical texts that came to be known as the Oxyrhynchus Papyri were found by British archaeologists Bernard Pyne Grenfell and Arthur Surridge Hunt in 1896 in excavations of an ancient midden, or garbage dump at Oxyrhynchus (modern name Al-Bahnasa) in Egypt. In studies over the last century, the texts were identified as previously unknown apocryphal sayings of Jesus. The earliest identified material published by Grenfell and Hunt in 1898 was from the Gospel of Thomas. In 2018, the Oxyrhynchus Society published new discoveries from the Gospel of Mark, in The Oxyrhynchus Papryi Volume 83 (2018), edited by Daniela Colomo and Dr. Obbink.

The MOTB alerted the EES to its concerns after doubts were raised about the provenance provided by Dr. Obbink. In October 2019, the MOTB announced the results of a joint investigation with the Egypt Exploration Society (EES) into thirteen of the museum’s papyri biblical texts. According to the MOTB, Hobby Lobby had purchased eleven of these texts from Dr. Obbink. The investigation found that not only were thirteen fragments held by the museum missing from the EES. In some cases, their catalog card reference and photographs had also disappeared. Professor Obbink was arrested on suspicion of theft and fraud in April of 2020; he has denied any wrongdoing. Investigations are said to be continuing.

Displays and excavations to build the case for historicity of the Bible

The exhibition space at the Museum of the Bible is non-standard as far as museum displays go. As Cultural Property News noted on the museum’s opening in 2017:

Museum of the Bible, Nazareth exhibition. Courtesy MOTB.

“The Museum of the Bible asks all people to “engage with the Bible” by showing the depth and breadth of its influence. Despite the inclusion of other approaches to Christianity and a bow to Judaic tradition, these exhibits have a bit of the feel of an “honorable mention” about them. The museum also seems designed to stun and amaze its visitors with technologically advanced displays. It features a virtual “flyby” in the exhibit Washington Revelations that highlights the areas around the capital where Biblical passages are cited or quoted. The museum also has an innovative digital guide for ease of navigation and planning. The World Stage Theater utilizes a digital 3-D mapping technique that allows the production to unfold around the audience.”

However, beyond the entertainment value so well captured in these exhibitions is an underlying message linked to an evangelical argument that the Bible is not only an expression of and testament to the true faith, it is true in the sense that it is factual and historical. Author Cavan Concannon has noted that this perspective carries over into the museum’s funding of archaeological work. He says, “The discipline of archaeology, as it is presented in the Museum’s exhibits, is understood to vouchsafe the stability and accuracy of the biblical text.” The argument that archaeology proves the truth of the Bible is certainly not new; it was the focus of much popular archaeology in the 19th and early 20th century (and in a way, goes back as far as the circular argument that relics such as the nails and fragments from the cross brought to Europe during the Crusades must be real because they perform miracles, and that miracles prove the authenticity of the relics).

The Museum of the Bible has also come under fire for its sponsorship of archaeological excavations in the West Bank. Archaeologist Michael Press has written about the Museum of the Bible’s funding of World of the Bible Ministries and Liberty University professor Randall Price’s excavations at Qumrun. Price claimed that the joint American-Israeli project located a twelfth Dead Sea Scrolls cave at Qumrun. While no scrolls were found in the excavation, Oren Gutfeld of Hebrew University said that, “The findings include the jars in which the scrolls and their covering were hidden, a leather strap for binding the scroll, a cloth that wrapped the scrolls, tendons and pieces of skin connecting fragments, and more.”

Press describes the excavation and removal of artifacts as “ethically dubious” given that due to its location, Israel, Jordan and Palestine all claim an ownership interest in the site. Numerous artifacts were taken during the actual 1967 war – a violation of the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict, to which Israel is signatory. Press also correctly notes that the Hague Convention restricts archaeological activity in occupied territory.

Press’ examination of the Museum of the Bible’s 990 non-profit tax filings shows that it provided more than $3 million in funding for scholarly research and publications related to the museum’s collections, much of which went to Christian educational institutions. Press also noted a very substantial grant of $225,311 to an unnamed individual for research into the Oxyrhynchus papyri. Press assumes, due to the research subject and the fact that Dr. Obbink is known to have done research for the museum , that this grant went to Dr. Obbink. (Press’ article predates the announcement of the theft of the EES papyri.)

Press describes the broader message of the museum’s archaeological sponsorship, research funding and the tenor and content of the museum’s displays as building “an implicit Christian — and particularly Protestant — bias throughout the museum’s narrative.” He asks, why does this matter? The museum does not deny that it is an evangelical Christian institution, although it is careful to remain inclusive of Jews in its telling of biblical history. Press sees more serious problems in how the Green’s and the museum’s money influences how research and study is directed – “what material is studied and what isn’t.” The MOTB will influence public perceptions of what biblical scholarship is, and its funding will result in at least implicit endorsement by academic scholars – further expanding its influence.

And, he says, “If there is a battle between Museum of the Bible funding and scholarly ethics in the study of the ancient world, then it appears that the money is winning. Hands down.”

Museum of the Bible, Giving of the Law exhibition. Courtesy MOTB.

Museum of the Bible, Giving of the Law exhibition. Courtesy MOTB.