A groundbreaking new book has been published by Factum Foundation, The Aura in the Age of Digital Materiality: Rethinking Preservation in the Shadow of an Uncertain Future (Silvana Editoriale, 2020). The publication was to accompany the opening of the exhibition, La Riscoperta di un Capolavoro (The Revealed Masterpiece) originally scheduled March 12-June 28, 2020 at the Palazzo Fava in Bologna, but now closed due to the coronavirus situation in Italy. Fortunately, the book itself is available not only in hard copy, but also through a download on the website of Factum Foundation.

The Aura in the Age of Digital Materiality is essential reading for everyone in the art, museum, and cultural heritage field. It is an extraordinary collection comprising some fifty essays by art historians and professionals in museums, architecture, the sciences, ethics, indigenous rights and other fields. Altogether, it is remarkable work of advocacy for connecting individuals, communities and countries through art.

Adam Lowe during his talk ‘Applying Technology Preserving the Past… Informing the Present’ at the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum in June 2018. © Bilbao Fine Arts Museum

The book and its many influential authors go far beyond the convention-bound approaches of institutions such as UNESCO and ICOMOS to challenge how we think about monuments and objects of art – how we stockpile or share them, and how digitization and documentation can facilitate a new dialog about art across cultures. Rather than focusing on technical issues of preservation and documentation – although tremendously informative about those processes – the book demands that we rethink our relationship to art, art history, and cultural heritage. For many of the contributing authors, the discussion continues and expands on the issues of originality and authenticity raised by Walter Benjamin’s seminal essay, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. In clear, precise language, they show how relevant individual memories and perceptions are to how we see art. An artwork, a restoration project, or specific experience shows how art has been seen by other people and cultures, sometimes over centuries, and raises surprising new questions for academics and historians. We leave the book with a broader understanding of the meaning of artworks and art scholarship as they exist within time and space, and a desire for more.

Otto Lowe demonstrating photogrammetry at the Shaden resort in AlUla, training programme carried out in collaboration with RCU and Art Jameel. © Annette Gibbons-Warren (RCU)

Factum Arte and the Factum Foundation for Digital Technology in Conservation have initiated and been part of numerous exhibitions, studies, conservation training, and unprecedented joint projects involving major artworks and monuments from around the world. A short list includes past works such as the recreation of Lamassu sculptures from the palace of Ashurnasirpal at Nimrud, the tomb of Tutankhamun, and Salviati’s Ceiling at Palazzo Grimani. Ongoing projects include training in photogrammetry in Saudi Arabia, documentation of the Birdman cult on Easter Island, reconstructing the lost silver map of al-Idrisi, digitization of works by Diego Velázquez, a facsimile of the Djehuty Garden in Luxor, and documenting, conserving and raising awareness about the Bakor monoliths of Nigeria.

Cultural Property News Editor Kate Fitz Gibbon spoke with founder Adam Lowe about Factum Arte, the Factum Foundation, the publication of The Aura in the Age of Digital Materiality and the varied calls to action that the book’s authors make.

INTERVIEW

Q: Why this book and why now?

Lowe: This is really quite a Bible – actually I think it’s an important publication. We did it relatively fast. As soon as we had agreed on all the details, we put the book together in three months and printed it. It’s an amazing line-up of writers.

Q: Let’s start with just one. Hartwig Fischer’s article, ‘Collections Entail Responsibilities,’ [also published in Cultural Property News in March] dives into the necessity for change at the British Museum and shows how differently the Museum is working already.

Lowe: I am very pleased that Hartwig agreed to include his essay Collections Entail Responsibilities in the book. We were talking a lot at the end of last year following the donation of facsimiles of two Lamassu to Mosul University. Factum actually recorded these in the Museum in 2004 but some things take time to find their right form. I have great respect for Hartwig. I think being a German director of the British Museum during the time of Brexit in the time of Brexit must be a very challenging job. The name ‘The British Museum’ is certainly problematic. The term ‘British’ has both nationalist and colonial overtones.

The installation of a facsimile of one of the lamassu from Ashurnasirpal’s palace at Nimrud, now in the British Museum, into the entrance of the student hall at the University of Mosul in 2019. © Luke Tchalenko for Factum Foundation

I am optimistic that something really remarkable can happen under his leadership. He is in charge of this absolutely cacophonous chatter of objects from all over the world that really inform each other. He is surrounded by scholarship and we are in a time when technology can help with both preservation and dissemination. I feel strongly that preservation should precede ownership, and, in a digital world, things like ownership can be renegotiated in new ways that aren’t just a binary: it’s not just ‘yours or mine’. Neil MacGreggor’s History of the World in 100 Objects showed there is a real appetite for this. But the debate is in flux and questions proliferate; how you can have shared ownership? How you can share data? How you can make it active? And how you can transform a discrete museum object into a vital subject?

40 or 50 years ago, going to museums was about admiring things out of context in an environment where aesthetic considerations dominated – rather than being deeply articulate subjects that allow you to get in and think about them, share, question and discuss them. To me, books, objects, paintings, come alive in the act of discussion. It’s very much about extracting the thought processes from the material evidence.

Q: We were talking about how that also happens with some contemporary art – like the work of the superb Russian photographer Boris Savelev, which Factum Arte has editioned. (Czernowitz 1978-2018 Boris Savelev, Printed and Published by Factum Arte.)

From the Bus, 2010. From the portfolio Boris Savelev 1978-2018 Chernowitz, © Boris Savelev

Lowe: Just think of Boris for a second. What I love about Boris is that, as you said, it’s like a direct access into his mind. I find, looking at Boris’s photographs, I see things in a way I haven’t seen them before. Seeing the world through someone else’s eyes can be an exceptionally alarming experience, but in Boris’s case it’s an exceptionally generous one. But I think the whole of what museum objects, historical objects and contemporary objects do, is actually to allow us to think thoughts that aren’t ours, to give us access to philosophies that we may not have experienced, or religions, or social structures or other things. Through, if you like, a forensic engagement, a close and careful engagement with a painting, an object, a sculpture, you start to read it. There’s a whole host of books like Vermeer’s Hat by Tim Brook, that looks at Vermeer through the hat he’s wearing and expands out into cultural trade at the time and the role of Holland at the time of Vermeer, etc. I do think there are obvious ways that works of art reveal things about the world, but they are also deeply subtle ones.

Q: Give us an example of a project you are engaged in now that is bringing new information on art and art history to light.

Lowe: One of the things we’re doing at the moment is working on a collection of Spanish paintings for Bishop Auckland in the north of England, where there is a remarkable group of paintings by Francisco de Zurbarán that were acquired by Jonathan Ruffer. He’s now building Auckland Castle, the Zurbarán center and the Spanish gallery. We’ve set up what I believe to be a very innovative structure. He has a good private collection of Spanish paintings and sculptures, it’s not comparable to the Prado, but it’s a very interesting collection assembled over recent years. What we’ve done is helped to build relationships between Jonathan Ruffer and for example Fundación Casa Ducal de Medinaceli, one of the oldest and greatest collections of buildings and objects in Spain, that is cared for by the Duke of Segorbe and the Medinaceli family. By high-resolution recording, by building facsimiles by taking, for example, Berruguete’s sarcophagus of Cardinal Tavera and showing it before and after the damage that it experienced during the Spanish Civil War, suddenly four or five subjects are intertwined.

Alonso Berruguete is not very well known outside Spain – he’s better known in America since the National Gallery did a show of him last year – but Berruguete’s work is amazing. He’s one of the great Renaissance sculptors who doesn’t really travel much because most of his things are too big and too fixed. He was one of the few Spanish artists who had a direct connection to Michelangelo, a very direct line bringing the Italian Renaissance tradition to Spain. Berruguete also painted a bit. His sepulchre of Cardinal Tavera is one of the amazing sculptures owned by Casa Ducal de Medinaceli. We’re making a facsimile that will initially be shown at Bishop Auckland, alongside Berruguete’s painting of Cardinal Tavera and the death mask he made to inform the sepulchre. And we show these together with an El Greco portrait of Tavera that was painted fifty years after his death, from the death mask – it’s a painting that Francis Bacon would have loved. Suddenly you’ve got a dialogue that crosses generations and introduces a wonderfully melodramatic Spanish take on the world.

Francesco del Cossa and Ercole de’Roberti. 1472-1473. Recording and realization of a facsimile of the Polittico Griffoni. The project involves 3D scanning and color recording of the 16 painted wood panels that form the work (now scattered around different museums in the world) with the intention of realizing a facsimile for the chapel of San Vicenzo Ferrer in the Basilica of San Petronio, Bologna.

If we can complete the display, there’s also a tabernacle which is one of the few sculptural works by El Greco, that’s also on display at the Hospital de Cardinal Tavera in Toledo. The figure of Christ resurrecting is enigmatic and thought provoking- I remember seeing it years ago in the Prado restoration studios. The tabernacle itself is incomplete, so based on drawings and historical research (and discussions with people who really know the subject), we’ll reconstruct the tabernacle to reveal how it might have worked as a dynamic object when it was paraded through the streets of Toledo in religious festivals with the figure of Christ resurrecting up through the tabernacle into a window at the top. For me this is the absolute joy, when history comes alive, when it can be interpreted, when it can actually give you access to things that are so easy to overlook, especially in an age where it’s increasingly difficult to gain access to things in a way that allows you to engage with them with time to reflect.

Q: I see parallels in what you do to the archaeological argument that context is everything, that without context an object is meaningless. You have turned the archaeological argument on its head by using other tools than stratigraphy to read history. Your work takes knowledge about the object itself, its construction, technique, and materials, and combines that with history as well as art history, documentation of communications between artists and artistic communities, and what you might call ‘extreme connoisseurship.’

Lowe: I love the idea that we are applying the practice of archaeology to art– forensic study is itself an artform. Archaeology is a great discipline, about reading layers of information, and trying to extract and identify information and facts out of stratigraphic readings of data and the analysis of materials.

Titian (1490-1576), The Flaying of Marsyas, circa 1570-1576, Kroměříž Archdiocesan Museum, Czech Republic.

What I think we do with the digital recording and the digital study is give people access to things. This began many years ago when I was at the Genius of Venice exhibition [Royal Academy, 1983-1984] and I was fascinated by the fact that every artist I knew, from Francis Bacon to Frank Auerbach to Lucien Freud to Leonard McComb to Craigie Aitchison – different groups of people, different painters, but everyone is transfixed by one painting – The Flaying of Marsyas. I was at the Royal College, just about to leave, very much a figurative painter trying to be a realist figurative painter but with a notion of realism that wasn’t photographic and wasn’t fixed – that was my obsession.

I started thinking about why painters were so interested in in Titian’s Flaying of Marsyas? In this show there were a lot of great paintings, so what is it about this painting? Strangely, it had two qualities. One was the subject of the painting: about skin. In the Flaying of Marsyas, the act of removing the skin is really this battle between Apollo and reason and Marsyas and emotion. Much more importantly than that, I discovered that the painting had no significant restoration history. That’s not something declared in the catalogue. Suddenly that was the eureka moment. I thought, if I can record the surface of paintings, this will reveal the fluid dynamics, the brush marks – it will focus on the paint itself– how it was applied, how its aged. Paint changes over time, it expands and then it shrinks, some of the pigments lose their opacity and others discolour. Ageing is dynamic. This idea that there’s originality, that there’s a fixed moment of originality, seems to me a misunderstanding of the inherent nature of what art is. By its nature, we’re constantly seeing it through new eyes, and its ability to reflect back something that we’re projecting onto it is part of the dialogue.

Q: What you see are the layers of history and a new set of questions?

Lowe: If you understand the material nature of something, and how it ages, this can open up into a whole lot of amazing conversations. I was talking to Stephen Greenblatt over dinner many years ago, and he said ‘could you really record a painting so accurately that I could make assumptions about surface and transparency? I said, ‘Well, up to a point. From surface recording I can tell certain things. From high resolution colour recording, I can tell other things. From a mix of those two things I can tell more things. With x-ray and infra-red and ultraviolet and historical data all layered together you can tell more things. Suddenly you can go through the surface.’ And Stephen said, ‘But Adam, what I’m really interested in is, was Lazarus painted to be greener than other figures in many of the paintings of Lazarus? Now it’s hard to tell, because white paint and skin tones become transparent, and were almost always painted over green under paint. So my interest is, was Lazarus more green than the Virgin Mary, for example, in a another painting, or more green than Christ resurrected? Christ at that point is not dead.’

Q: How can you account for the changes – or know the intent of the artist at that time specifically? And these are artists who encountered people who were dead, who are green.

Lowe: That’s right! Stephen’s argument is that, what happens in the painting as it ages, skin becomes green, not because they’re dead, but because the white becomes transparent and there’s a green under painting. The question is, would we be able to ascertain whether the Lazarus was painted intentionally green, even though now he’s aged to being green? It’s this kind of question that I love. The poetry that lies in the act of looking very hard – that’s what Boris Savelev’s photos are about, that moment when you actually see something.

Adam Lowe standing in front of Factum Arte’s facsimile of the Wedding at Cana in Palladio’s refectory on the island of San Giorgio Maggiore, Venice, the space for which the original was conceived and painted. © Factum Arte

The greatest privilege that I have now – I’ll come back to how we got there – to be able to spend five weeks every night recording and working with Caravaggio’s three paintings in San Luigi dei Francesi, or spending about the same time in the Louvre recording the Wedding at Cana. In that case, the real privilege was not only being with the Wedding at Cana, but having the Mona Lisa there all the time, and you can look at it, because they’re in the same room. To be able to look at a painting like that, without anybody else present – but also with a few of my team who share interesting ways of looking and thinking. To me, the kind of work we’re doing is a little bit like going on a long car drive, those ones you must be experienced with in America. Your body is doing enough things for your mind to be completely free. There’s a sort of repetition, and I tend to have many of my most lucid thoughts in that state. When you’re recording a painting, to be able to look at it, but still be busy – the idea of sitting and looking as a passive thing, receiving information, is very different to looking actively.

Q: Your brain is going to work differently, and you’ll end up with different questions.

Lowe: That’s right! We tend to see things, notice something. The second part of the privilege is working with amazing people. In the Berruguete exhibition, C.D. Dickerson who was the curator of that show was here with Juan Manuel Albendea who runs the Fundatión Casa Ducal de Medinaceli, who knows Berrugeute’s work so well. Or working with Matthias Wivel and Gabriele Finaldi (who was at the Prado and is now at the National Gallery), or Faiza Haikal and Salima Ikram in Egypt or Ali AlJuboori in Mosul – any number of people we work with on different projects, many of whom have written in the book. You go really deep, and for me the great joy is not just gathering the data but gathering the data and then entering into the dialogue…sharing ideas.

Q: Does that dialogue result in a different kind of curatorial presentation? I am thinking about the essay in the book by Bryan Markowitz on the Scanning Seti exhibition at Basel’s Antikenmuseum. He describes the poetic powers of museums, how they can ‘police’ fact and fiction. He shows how underneath the mystery and Gothic overtones of museums’ presentations of Egyptian artifacts, Factum Arte’s work also ‘asks us to see the Ancient Egyptians’ religious devotion through the aesthetic and moral quandaries that a precision reproduction presents.’ That’s deep.

Lowe: To me there are those little moments in life that absolutely amaze me. I got more or less that essay – this is a slight exaggeration, but not very big – more or less that essay, as an email from Bryan who visited the exhibition in Basel. For me, that was just the greatest sense. Charlotte Skene Catling who designed the exhibition and helped frame the subject – her essay in the publication is about Boucher, the Madame de Pompadour in the Frame exhibition at Waddesdon Manor. Charlotte and I worked very closely on the exhibition design and thinking it through. But actually, how do you tell stories? I mean most exhibitions tend to adopt as you say a kind of didactic tone, they’re telling you something. For me an exhibition should be an active journey of discovery– you need the curators to embed their ideas in a way that leads people and allows ideas to percolate. But they need to allow the objects to reveal their biographies allowing the visitor to make the discoveries for themselves. They should not be told what to think. If you understand how the visual logic works, you can kind of lead someone through an experience, which is what a great exhibition does.

Carlos Bayod and Aliaa Ismail recording in the tomb with Lucida 3D Scanners, 2016. © Factum Foundation

If I think about some of the great exhibitions I’ve ever seen: Jean Claire, ‘L’âme au corps,’[1] is one of the great exhibitions. Jean Claire would be up there as one of the great exhibition curators. One or two of Norman Rosenthal’s shows at the Royal Academy I think really get there. But that email I got from Bryan Markowitz, someone I had never met until he travelled to Madrid after spending several days in Basel, confirmed that it really is possible to share complex ideas. He went to the exhibition in Basel and writes something which more or less corresponded exactly to the conversations Charlotte and I were having. That’s the moment when you know you’re communicating.

Q: Do you relish the role of showman as well as scientist?

Lowe: I don’t think of myself as a scientist or a showman. The truth is, this is a bit of a difficult one, I try to deal with this in the conclusion to the book. The truth is I think like a painter. I never touched a computer until I was 34. I didn’t have a mobile phone until I had to around the end of the millennium. I’m a Luddite when it comes to technology. My son, who is now in charge of a large part of the 3-D recording at Factum, particularly the photogrammetry, teases me that I can hardly use email, let alone do anything more complicated. But I have a totally different set of skills around reading, looking at, analyzing, responding to, knowing what’s important in what we record – and demanding that we record things differently and with more correspondence to the object. For thirty years I’ve been trying to record the surface of paintings – no more than that. What has become increasingly clear is that digital artisans and physical artisans need to work together.

Q: But you’re always testing that. You don’t accept anything without recording it, testing it, making sure it’s there.

Lowe: That’s true, but I would preface this by saying that in 2000, with Simon Schaffer, a great historian of science (Boris Savelev has a generous eye and Simon has a generous mind!), I curated an exhibition that I’m still very proud of, called Noise. It was at four museums in Cambridge and the Wellcome Institute in London. It was an exhibition about noise and information, in all their aspects, which had, I think a hundred different people involved, five Nobel prize winners, it crossed so many professional boundaries but we never used the words art or science. The only ground rule was, we don’t judge any one for being either a scientist or an artist. It’s all about the relationship between noise and information – about understanding the physical world. When the radio is tuned between channels, that’s white noise. Noise, not sound. Everything we do in Factum is about the relationship between information and noise. The important thing to remember is that the radio, or the television tuned between channels, actually contains more information than if it’s only tuned to one channel. How you prioritise, access, differentiate between foreground and background, figure and ground is dependent on hundreds of decisions made by many people. One of my favourite works we have made at Factum was Mindful Hands[2] a film made by Luke Tchalenko that follows every action from the killing of the goat, the making of the vellum, the production of the pigments, the binding agents in the paint, the brushes and application of paint, the binding into book form. I like to think that Factum is an example of teams of people working together with different types of embedded knowledge and no professional barriers. The fact that I was pre-digital meant that in a digital age I needed to be part of a team because no one person can do everything. I started Factum Arte with Manuel Franquelo, who is a painter and an engineer. We were joined by Pedro Miró, who is a free-thinking digital trouble-shooter – sometimes brilliant, sometimes the noise dominates – but that’s part of life. When you are trying to build a team that is doing things that haven’t been done before you very quickly realise that detailed and specific communication is exceptionally difficult. [Mindful Hands trailer.]

There’s an interesting video that was made recently with Bank of Santander about this subject. I was working with Ana Botin to look at different notions of value. I think this is the really critical social issue now….in a post coronavirus age the relationship and understanding of both creativity and money will change dramatically. Banco Santander and Factum reflect very different value systems. There’s something I like very much in this film and as a result of this engagement and dialogue Banco Santander created ‘Fondo Smart’ to help creative businesses – it probably doesn’t go far enough but it’s a very positive start of a process of re-evaluation. [Bank of Santander video]

Ferdinand Saumarez Smith recording one of the Bakor Monoliths in Nigeria. © Factum Foundation

Q: Looking at value systems that are very different is one of the things that I wanted to talk about. Simon Schaffer’s essay in the book also seems deeply informed by his wife Anita Herle’s work. [Dr. Herle is Senior Curator at the University of Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology and a world-renowned specialist in Oceania.]

Lowe: Yes, that’s true. Anita and Simon are an amazing pair who give to and take so much from each other. When we did Noise, one of the venues was the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in Cambridge and there were many very rich conversations that I am still digesting. The relationship with indigenous communities in Torres Straits Island and the work that Simon has done with Anita over many years in Canada – of course that feeds and informs what he wrote for the Aura in the Age of Digital Materiality. The essay that Simon wrote grew out of some work that Factum have been doing with indigenous communities in Mato Grosso and a presentation we gave together at CRASSH in Cambridge. (Clare Foster who runs CRASSH has also provided a text for the book.) Simon’s essay is sandwiched between Hartwig Fischer’s text and a description written by Ferdinand Saumarez Smith about the work we are doing in Cross River State with the Trust for African Rock Art. When Factum started the project to record the Bakor monoliths it was impossible to predict what would follow. The first trip was funded by Paula and Jim Crown from Chicago – they have been great friends and supporters of the foundation making it possible to start projects that would otherwise not have happened. They put up $15,000 to help us send a team to Nigeria to start recording some of these monoliths in three dimensions and to build a relationship with the University of Calabar. While he was there Ferdie started talking to some of the local community leaders and started to understand the problems of preserving the monoliths. Most of our work only makes sense looking backwards, it’s a journey of discovery. It’s a very important part of how Factum works, that don’t always know where we will end up when we begin. Most grant applications tend to be targeted with predetermined outcomes. Factum has never been very good at getting grants as our work is focused on engagement, understanding local needs, transferring skills and technologies and helping to establish an infrastructure that prioritizes the preservation of articulate objects. Factum’s work tends to be focused but untargeted, and I think this is a very different way of thinking.

In conversation Ferdie discovered that half of one of the monoliths was now in a major museum and that many other monoliths had been removed. The last survey was carried out in the 60’s by Philip Allison. This archive, now in the Bodleian Library in Oxford, was published in 1969, when the Biafran Civil War was at its height. It seems that many monoliths were removed at this time but we soon found that the removal of these UNESCO listed works is still happening. It took about fifteen minutes to find that the missing top half of that monolith was in the Metropolitan Museum, in New York. Yaëlle Biro and Alisa LaGamma at the Met were very helpful and we were given permission to send a team to the museum to scan it. We wanted to make a direct comparison between the top half in NY and the bottom half that remained in its original location. We proposed making a facsimile of each part so that a complete monolith could exist in both sites.

The Lucida 3D Scanner recording the surface of the walls in the tomb of Seti I © Factum Foundation

The UNESCO second convention on the trading of illicit goods was formulated in 1970. Allison’s work was published in 1969 so our work started to take a different direction and Ferdinand and the rest of the team started searching for monoliths that appear in Philip Allison’s documentation but are no longer in Nigeria. The next one we found was in Quai Branly, so we obtained permission and recorded this. Technology played a part in the next discovery – during an Instagram search it appeared in the background of a photograph taken in a garden on Long Island. We eventually identified the owners and talked to them, but the Monolith had been donated to the Israel Museum. We got permission and recorded this in the autumn of 2019. But while these negotiations were going on, we got lucky. We found one with a dealer in Brussels. He allowed us to go to his warehouse to record it. While we were there we recorded two monoliths. Neither was the one we went to record. So they definitely had three. Then looking at a book published by the collector and dealer Pierre Dartevelle we saw a photograph of another that can be clearly identified as one recorded by Allison. This kind of research takes time. It is unpredictable. It raises many more questions than it answers. It demands much more work.

My interest is long term preservation and both communicating and understanding the objects themselves. It is for museum professionals, lawyers and politicians to make moral judgements about ownership and repatriation. What we’ve done, and what I hope we will still be able to do with the British Museum in October to celebrate the 50th anniversary of UNESCO’s second convention, is do create an exhibition that can raise many questions about what these monoliths are, how they are being moved around the world, how they are best looked after, where they can be most appreciated and understood, why they are being copied, how can they help the local communities whose ancestors made them and how they can be shared in future.

The story just gets richer and richer. And takes new twists and turns. The British Museum has a Bakor monolith that was acquired in the 1970s. We found a very similar one in the Israel Museum and another almost identical one was recently purchased by a museum in New Orleans. Documentation of all kinds informs Factum’s work and video was recorded of two stone carvers who are producing monoliths now. When shown photograph of the British Museum’s monolith they both said; ‘that’s a modern stone.’ These guys should know – they make them.

The more you start to put your story together, the richer and more complicated that story becomes.

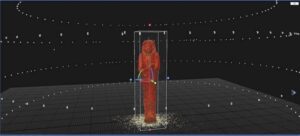

Ushabti. RealityCapture showing the different camera positions used to create the photogrammetry model © Factum Foundation

Working with the Carène Foundation, we’re going to design the BM show so that it can travel within Nigeria. It won’t contain original objects so it can travel to places without climate-controlled conditions. The objects will be able to visit the sites they originally came from. Assuming we can finalise all the permissions we will leave a copy at its original site and we will work with the communities to teach them how to do high-resolution photogrammetry in order to create a complete archive of all the monoliths at each site. Thanks to the generosity of the Carène Foundation we will set up a small didactic museum in Alok where we’ve been offered a building to act as a focal point….a living archive helping to preserve the monoliths wherever they are. Our task will be to create a detailed high-resolution archive of all the monoliths in their current condition. This will be vital to monitor their condition and to track their movements.

I always remember a very old friend of mine who is an antiquarian and book dealer. He owned an amazing book, and I remember saying to him once, where did he think it would end up, I assumed it would go to a library. He said, ‘Probably, but I hope not. That’s like sending it to prison with no parole. In a library no one can handle it, it’s not something that can be shared. It will be digitized and locked away.’ Using technology to bring things back into the physical domain while exploiting the ability to share data around the world has become Factum’s main task. It’s also a recurrent theme in the Aura in the Age of Digital Materiality. There is a picture taken in the Louvre followed by a picture of the facsimile of the Wedding at Cana in Palladio’s refectory at the Fondazione Giorgio Cini…. In one you can’t see the painting – in the other you can contemplate a facsimile in its intended location.

Q: This a photograph taken in the Louvre where everybody’s looking at the Mona Lisa and nobody’s looking at the Wedding at Cana?

Lowe: No one can look at anything in that context. If you want to study either the Mona Lisa, or Veronese’s Wedding at Cana, you need privileged access. Susan Tallman wrote a very good piece entitled The New Real in 2009, in Art in America. I think hers is one of the early pieces that picks up what’s going on and what we are doing. She said, ‘no one argues that the heavily restored, repainted version hanging at the wrong height, in a gold frame that it was never intended to have, on a shitty brown polished plaster wall, with zenithal light in the Louvre, is in large part original. But is the experience of seeing a copy of the level of exactness of our copy, in its intended location, without a frame, hanging at the right height, with the light conditions that it was painted for, more authentic than the experience of seeing it at the Louvre?’ And the answer without doubt is that the experience is more authentic in Venice. What we’ve done is to separate originality from authenticity. Of course if you want to study the pigment, if you want to analyze it, if you want to really look in different ways, you’d need to go to the Louvre at night, or when the museum’s closed. Ideally you need to see it without a frame. You’d need to look at what was done to it.

This is all in a book that was published by Cierre Edizioni for the Fondazione Giorgio Cini entitled The Miracle of Cana – the Originality of the Reproduction. It was edited by Pasquale Gagliardi and contains essays by Giusippe Pavanello, Bruno Latour, Simon Schaffer. The Cini also published the talks form the Dialoggo di San Giorgio in 2008, – Coping with the Past. It contains the essay we reprinted in the Aura in the Age of Digital Materiality by Richard Powers, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Overstory. He observed; ‘I have been listening to this group move toward a provisional starting point for how we might begin to tell impoverishing stories from enriching ones: impoverishing narratives collapse reciprocal, dynamic processes into amnesiac packaged products. Enriching narratives release products into long-time processes. Bad stories are full of monolithic, privileged certainties that stop time and collapse focal perspective to a controlling view. Good stories move the reader freely across all three tenses, through a country full of voices. Bad stories get us to side with the hero. Good stories get us to change sides, and even to change the sides themselves.’

The lamassu were recreated using scagliola (plaster marble), a material that can be made to closely resemble the Mosul marble from which the original statues were carved. © Luke Tchalenko for Factum Foundation

Q: To me what Factum Arte and Factum Foundation do better than anyone is re-invigorate the study of art, in and outside of museums.

Lowe: That’s what we set out to do. We try to tell enriching stories in new ways that allow people to think freely and ask complex and pertinent questions. The first project we did with Hartwig Fischer at the British Museum involved the return of two exact facsimiles of the Lamassu from the palace of Ashurnasirpal II in Nimrud to the University of Mosul. It was one of the most emotional things I have done. In collaboration with the Spanish ambassador in Iraq, the Spanish Ministry of Defence and Mosul University, the two vast Lamassu were shipped from Madrid to Mosul and installed at the entrance to the student building next to the University Library that had been bombed by the US air force before being totally destroyed by Islamic State. Seeing a library of over one million books and manuscripts destroyed only reinforced the need to digitize and spread knowledge. This was the time when Hartwig and I really started talking – I hope that the British Museum is going to do something unbelievably bold and bring Factum Foundation in to help launch a programme of high-resolution recording, archiving and storytelling. This would be the best way to demonstrate that the BM is really addressing its role as a museum of world culture.

The reason I talked at length about the Bakor monoliths is because it shows how all issues of preservation are far more subtle than the type of post-colonial theory contained in the Savoy/Sarr report for President Macron. Here the focus is on the argument of ownership, of righting colonial wrongs, of sending these things back.

Q: But it’s only a fraction of the argument, of the facts.

Lowe: While all of them are important, they bring with them costs which many countries cannot afford or don’t have the infrastructure to provide. This topic needs to be opened up not closed down by nationalist and impoverished agendas.

You have to create the environment, where these things bring benefit, rather than bring cost. I believe there will be a moment when there can be a fluid flow of objects (in both original and facsimile form), that really allow history to be seen very differently. This is a theme that runs through Simon [Schaffer]’s essay, where you hear Anita [Herle]’s voice – I hear it too, very strongly. Simon is very clear about reasons to return and not to return artefacts. I have had very insightful conversations with him about reasons why communities may not want things back – for example Maoris regard their objects as being like ambassadors taking the Maori point of view around the world – expelling an ambassador is not constructive. Many people on the Torres Straits Islands were converted to Christianity but they are fully aware of the power of their artefacts, and they don’t want them back. Then there are communities where the objects served a ceremonial function after which they were discarded. If Europeans value this waste that was left to rot, that is up to them. There are many ways of looking at and thinking about objects and they tell many different stories. Objects migrate for different reasons. Some need correction, some don’t.

Abdel Raheem Ghaba, Amany Hassan Mohamed and Mahmoud Salem scanning with two Lucida 3D Scanners in 2019. © Gabriel Scarpa for Factum Foundation

Much more important for me than the question of repatriation is one of empowerment. How can culture give the local community work and a source of income that leads to heritage being valued and preserved? In the Valley of the Kings, which is the last section of the book, Factum Foundation and the University of Basel are working with the Ministry of Antiquities to run the Theban Necropolis Preservation Initiative. A team of ten people have now been equipped and are being paid well to digitize and record in the Valley of the Kings. It costs less to run a full Egyptian team, all of whom are from the West Bank in Luxor except Aliaa Ishmail, who is a graduate of the American University in Cairo. This creates a local economy, and it transfers skills and technologies. Why is UNESCO not doing this? Why are the people who are supposedly looking after culture not actually empowering local communities to do precisely that?

Recently I was talking to the Minister of Culture and the Swiss ambassador in Cairo. They want people to focus on this initiative as it is one of the very few examples of capacity building that is really effective. Theban Necropolis Preservation Initiative has been going on for eight years. It has carried out the full restoration of Hassan Fathy’s Stoppelaere House with the Tarek Waly Centre for Architecture and Heritage and it has generated revenue for the ministry from the exhibition in Basel. During this time we have received a couple of small donations, but the work has been entirely funded by Factum. And what does it cost? The direct costs are about 15,000 euros a month. We have been working in Egypt for 20 years. I’m amazed in all this time that we have never found a philanthropist to support the work: it is so rewarding – you get far more out than you put in.

The Hall of Beauties re-created following watercolours produced by Alessandro Ricci for Belzoni, for the exhibition Scanning Seti: the Regeneration of a Pharaonic Tomb at the Antikenmuseum Basel, 2017-2018. © Oak Taylor Smith for Factum Foundation

Q: Perhaps you’re telling a different story from what UNESCO wants to hear.

Lowe: Perhaps…. You asked me about ReACH[3]. ReACH began when Ferdinand Saumarez Smith and I went to Bill Sherman at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 2017 and pointed out that it was the 150th anniversary of the 1867 Convention for Promoting Universally Reproductions of Works of Art for the Benefit of Museums of All Countries. That was Henry Cole’s great opening gambit for the V&A, and the cast courts were all built as a result of this initiative. Factum introduced the Peri Charitable Foundation (with whom we were working in Dagestan and other parts of Russia). The aim was to make the discussions international – the opposite of the colonial royal powers who were the main signatories of the initial convention.

ReACH stands for the REproduction of Art and Cultural Heritage. For me it means the recording of art and cultural heritage. Without high-resolution recording, you can’t have a good reproduction. The reproduction is one of the outcomes of good quality recording. In a way, everyone says, Factum makes facsimiles. Yes, we do. The facsimiles are evidence that you can, for example, go and record a painting by Raphael, El Greco or Velazquez and bring the data back to the studios where it is assembled into a complete archive from which we can recreate the surface and colour at 1:1. The result can then be compared side-by-side with the original source. If we have done our work correctly it should be identical under normal viewing conditions in terms of shape, size, colour and surface. We did this with a Boucher from Lord Rothschild’s collection. The two now hang side-by-side in the exhibition Madame de Pompadour in the Frame… Are there differences… Yes, but they are really so small that they force you to look far more carefully than you are accustomed to.

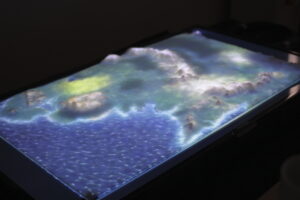

The 3D map of the Tolkien’s Middle-earth at the Bodleian Library, Oxford. © Factum Arte

Reproductions in a book don’t replicate an object properly; scale, surface and colour are normally lacking. More importantly, images are prepared with a white balance that changes the tonal range and contrast so it can be lithographically or, (more frequently now), digitally printed. A good-looking reproduction in a book is normally very different from the way the painting or object looks. It’s not a true reflection of what the ‘thing’ is like. The fact that most art historians now do most of their art history from secondary sources fascinates me. It’s understandable now that museums are so crowded and so many things are stored away in freeports. But unless the secondary sources contain the right information, you’re not going to observe the right things. I would much rather use images like Aby Warburg. Postcards, reproductions, black-and-white slides, an epidiascope projection of the page from a book and photocopies don’t pretend to be the things themselves. They are simply pointers that facilitate discussion – they don’t stand in for the object. You need to know the object as well as knowing the context. In a way, what we’re doing is merging what Piranesi was doing by valuing the object as its own evidence, and the philological approach that Winckelmann introduced. You’ve got these two sides coming together. It’s a mixture of academic study and observation, always prioritizing the object as the primary source of evidence. It’s a new age of digital connoisseurship that is going to transform our access to and understanding of the evidence of the past.

Q: You work with modern artists in the same way, going to immense trouble to achieve the artist’s goal. We had a connection before we met, in knowing the great Russian photographer Boris Savelev.

Lowe: As I mentioned earlier, I started working with Boris in the mid 1990’s, before Factum Arte started. I was involved in pigment transfer printing at that time – trying to get the photograph to work with a manual expressive mark like a brushstroke on the same surface… That meant I had to get them to be made of the same, or at least compatible, materials. Pigment and gelatin seemed to be the answer. I was making the photographs in sensitized pigmented gelatin and inter-layering them with more gestural marks. It took me far longer than I’d ever dreamt and it brought me into contact with people like Anish Kapoor, Sarah Moon, Richard Hamilton, Jeff Wall and Boris Savelev.

Yellow Boots, 1991. From the portfolio Boris Savelev 1978-2018 Chernowitz, © Boris Savelev.

Boris appeared out of the blue – I never quite understood how he found me in my studio near London Bridge. There was a shop in Waterloo called SilverPrint that sold photographic materials, and all the Russians would get the things they needed to print with historic processes. One of Boris’s friends, I think it was Valerie Orlov, had gone there to buy chemicals for Boris. He talked to the owner, Martin Reid – and Martin had said ‘Oh there’s a mad artist I know doing pigment transfer prints,’ and that got back to Boris. So when Boris started working with his German gallery, M Bochum, and they said they wanted to do an edition of photographs. Boris said they had to be pigment transfer prints and there was only one person who could do it. We ended up in this strange situation where Boris probably knew far more about pigment transfer printing than I did. With Michael Ward we started working together to make his prints exactly as he wanted them. That’s really what I’ve done ever since with different artists.

Many people are quite surprised by the way Factum works. I’m a painter and I worked as an artist through until about the late ‘90s. I was stopping painting in my own name about the time I met Boris. At that time I was concerned with representation and how paintings could capture the physical world we inhabit. It links directly to my interest and why I’m now in Spain. From looking at Velázquez, looking at Valdés Leal and many Spanish artists, it seemed to me that they actually were very consciously trying to articulate in the language of paint a fleeting ephemeral world seen from a human viewpoint with a divine, constant, non-perspectival representation, Often this was happening within the same painting.

Q: The book is full of essays that deal with specific objects and their history and then raise giant questions about how we look at art and how we can do better and change the way we think about it, whether its ancient or contemporary. But it also includes strange serendipitous happenings that seem to take place around art. That make art history seem human and right, and funny too.

Lowe: Serendipity makes me feel that things are on the right lines. As I talk to you I am looking at a white relief 3D print made with Océ’s elevated printing technology. It is the surface of a painting by Monet that was destroyed in a fire in MoMA in 1958. There’s a series of television programs we made with Ballandi Film for Sky Arts. We have now made eight one-hour programs about great paintings destroyed in the twentieth century. One of them was about a Monet painting of Waterlilies.

When we were asked to make this program I first tried to get the best reproduction I could. I talked to the conservation department at MoMA, they sent me a little black-and-white reproduction. I went and saw the conservation department on my next visit to New York, and we had a very interesting meeting. I said I really needed to see all the records they have about this painting and its destruction. Surprisingly they said they didn’t have much. It was destroyed in a fire in 1958, it had been bought a few years earlier and had been constantly on display. It was highly celebrated amongst the New York painters at the time. It had a real impact on Abstract Expressionist painters who were able to experience the field of light and colour and see what Monet was doing with his Grand Designs, he was effectively creating painted environments that immersed the viewer in the materiality of paint and gesture. I asked what had happened to the destroyed canvas? Was it burnt to a shred? Most of the things were fire damaged but some part of the work remained. The team working at the museum didn’t know what had happened to the canvas but said they could search the records that followed the insurance claim. It was a good settlement and with the insurance money they bought new paintings from the artist’s estate.

I teach at Columbia, a practical course on how to do what Factum does. We were doing a midterm crit, and Carlos Bayod, with whom I teach, had invited Michele Marincola, who teaches conservation at NYU. In a break we were talking about what was going on in Factum. I mentioned the meeting at MoMA and the challenge to remake the lost Monet. Michele said, “Adam, it’s in my office.” After the fire, the painting was considered a total loss and used by the students as a test for patching fire damaged paintings. We sought permission to record it. This was done as a joint teaching exercise. The digital restoration then began to remove the patches stuck on by the students and remove any blisters caused by the heat. While the painting was a mess the surface was remarkably intact.

The colour has been turned a greyish black but with analysis and a lot of light it was possible to establish the colours Monet had used and with reference to a painting in the Met we introduced subtle transitions of colour, hue and tone. The surface and the reconstruction are on show in the exhibition in Bologna alongside a Van Gogh Sunflowers that was recreated with the help of the National Gallery in London. This kind of serendipity happens a lot…When it does, I think we are on the right track.

Q: What will Factum Arte and the Foundation change next in the history of art?

Lowe: We are trying to develop a self-learning software for reading artworks, together with Elizabeth Bolman and physics professor Ken Singer from Case Western Reserve University. In The Aura in the Age of Digital Materiality there’s a brief text I wrote about what we are trying to understand about El Greco. We’re trying to see whether we can read the difference between the hand of one person and the hand of another in the three-dimensional traces left on the paint surface, which is right back to where I began, with Titian and the Flaying of Marsyas. If we can do it, it’s going to change art history. The first tests run by Ken are surprisingly accurate. If the fluid dynamics of the paint and the movement of the brush can reveal the identity of the artist and the presence of more than one hand in many, if not most, paintings, it’s a very exciting moment… If we can identify, from the surface of the painting, the hand of El Greco, the hand of his son, and the hands of other people from the studio, and possibly the hand of different restorers and conservators, then we are at a turning point that will facilitate a dynamic approach to painting, its initial production, its ageing and its conservation. I especially enjoy the fact that El Greco, even though he’s an idiosyncratic painter, worked with a studio and copying systems.

I would use Goya as another example. We have recorded all of Goya’s black paintings at high resolution, in 3D and color, in a project with Manuela Mena and the Prado. I’m disappointed that this data isn’t yet in the public domain. That’s an incredible exciting moment, that will lead to a much deeper understanding of what Goya did, and how the paintings might have changed since they were removed from the walls of the Quinta del Sordo.

New technology may involve the undoing of some prejudices and deeply entrenched points of view – but it will lead to a new era of preservation and sharing…we still need to solve the critical problem of long-term storage of digital data…but we are working on this too.

[1]See L’âme au corps arts et sciences 1793-1993 : catalogue réalisé sous la direction de Jean Clair : Galeries nationales du Grand Palais 19 Octobe 1993-24 January 1994. Paris : Réunion des musées nationaux [with] Gallimard /Electa, 1993.

[2] The exhibition Mindful Hands. Masterpieces of Illumination was a collaboration between the Fondazione Giorgio Cini, Michele de Lucchi and Factum Arte, shown at the Fondazione Giorgio Cini in Venice in 2017.

[3] The initiative “Reproduction of Works of Art and Cultural Heritage” (ReACH) was spearheaded by the Victoria & Albert Museum London in partnership with the Ziyavudin Magomedov Charitable Foundation Peri, was launched on International Museum Day, at an event jointly organized by UNESCO and the V&A at UNESCO Headquarters on 18 May 2017.

Detail of the facsimile of St Lucy. As part of the process of re-creating the Polittico Griffoni, some of the panels were hand gilt by Factum Arte´s restorer. The original, painted by Francesco del Cossa, is in the collection of the National Gallery of Art, Washington. © Oak Taylor Smith for Factum Foundation.

Detail of the facsimile of St Lucy. As part of the process of re-creating the Polittico Griffoni, some of the panels were hand gilt by Factum Arte´s restorer. The original, painted by Francesco del Cossa, is in the collection of the National Gallery of Art, Washington. © Oak Taylor Smith for Factum Foundation.