Joanna van der Lande

Joanna van der Lande has worked in the art and auction business for over 30 years. Having read Ancient History and Archaeology at Birmingham University in the 1980s she set up the Antiquities Department at Bonhams Auction house, London in 1990. She served on the UK Ministerial Advisory Panel on Illicit Trade (ITAP) from 2000 until it was disbanded in 2006. It was ITAP who advised the UK Government to accede to the 1970 UNESCO Convention. She is current Chair of the UK based Antiquities Dealers’ Association. She advised the UK Government on aspects of the Cultural Property (Armed Conflicts) Act 2017. She regularly chairs vetting committees at London based art fairs. She is an independent consultant providing valuations and advising on authenticity, provenance and political issues affecting the antiquities market, while also acting as a valuer to the Treasure Valuation Committee, the Government body responsible for establishing the value for UK treasure finds.

This article presents the perspective of a professional within the antiquities trade on the evolution of the market since 1989. It is based on an article that will be published by UNIDROIT later in 2021.

This is Part 1 of a three-part article and contains the following sections:

- Introduction

- Background

- Terms: antiquities, cultural goods, legitimate, illicit, important, and provenance all lack definition

- Academic relations with the trade and the question of provenance

- “Orphan” antiquities and provenance research

- The 2000 date

- Export licenses from source countries – how useful are they?

- Part 2 : archives, transparency and changing practices, fighting crime, false data, seizures, and the internet.

- Part 3 : the law, European Union and U.S. developments, art fair seizures, legal trade, orphans and fair compensation, and the way forward.

Introduction

Beginnings

Anne Claude Philippe, Comte de Caylus, 1692-1765, Recueil d’antiquités égyptiennes, étrusques, greques et romaines, 1752. Boston Public Library.

On graduation from University in the late 1980s, with an ancient history and archaeology degree, I discovered there were art dealers buying and selling ancient artefacts. I took up the opportunity to work for a reputable dealer in the West End of London; I was soon hooked. After over thirty years of handling and living with artefacts made often thousands of years ago, the perspective this has given me feels like a gift. Some of these objects are undoubtedly beautiful, while others are mundane, but all were hand-crafted by now lost cultures. Handling objects creates intimacy. Like us, the creators of these artefacts were people who lived their lives for better or for worse and we exist because of them – they are tangible evidence of who we are and where we come from.

The dealer I worked for produced small academic catalogues, useful for identification and provenance to this day. Many of the prices were surprisingly low – affordable for the school teacher as well as the tycoon. All of us prioritise how we spend our money and some collectors I’ve known live very modestly but with a passion and a discerning eye; they have put together collections of ancient artefacts which has undoubtedly brought their lives greater meaning and joy. Most buy the best they can with available resources and it is perfectly possible to collect ancient artefacts for modest amounts of money.

Why antiquities and not copies?

Sophia Schliemann, wearing “the treasure of Príam,” discovered in the excavation of ruins believed to be Troy.

Put simply, a plaster copy does not connect us to the past in the way an object created over 1000 years ago does. They are a silent, yet physical testimony to the time and society in which they were made. This is powerful stuff – it roots us. A colleague in the trade shared with me why a small crudely made cosmetic pot with a commercial value of less than £50 is a favourite antiquity from his private collection – inside it has a fingerprint of the person who made it 3000 years ago. This direct connection with the past has been repeatedly mentioned to me by colleagues as the reason they love handling ancient objects. This connection with an object has the capacity to transport one’s imagination to a different place and time.

Tales of Greek heroes and the epic story of Troy fueled the imagination of another dealer as a small boy, who said they pointed to a “brightly coloured, epic past, vastly different from the mundane market town in Oxfordshire” where he grew up. Yes, we can view antiquities behind glass in a museum which in itself is a wonderful privilege, all the more so now when we have felt so deprived these past months during the pandemic. For many, or indeed most people, seeing objects in museums is enough, but for

Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo (1727–1804) Procession of the Trojan Horse in Troy, circa 1760, National Gallery, London.

others this lacks the intimacy and spark of having an ancient object in one’s everyday life where it is possible to be touched by what has gone before us, to study and discuss with others – a past-time enjoyed for many centuries.[1]

The collecting instinct is deeply embedded in our psyche[2]. One of the benefits of the past decades of often rancorous debate has been the increasing requirement to carry out more research into the provenance of objects, which has often meant their more recent above-ground histories have been unearthed and recorded, revealing how this history of knowledge has been recycled and will continue to be so for future generations – collectors are but temporary custodians. There is now a sense of greater responsibility in passing on and sharing knowledge rather than just keeping it to oneself.

The role of museums and the private collector

Installation view, Parthenon marbles in the exhibition Defining Beauty, British Museum. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Many voices criticise the private collecting of antiquities because the objects are not available for the public to see. I can understand this sentiment when it comes to exceptional objects, but the vast majority of objects are not exceptional and are well represented in public collections. While there is too little said about how much is not on public display in museums, and while it can be possible to ask permission to study these objects, this is not in reality a possibility for the majority of the general public. For many museums only a tiny fraction of their collections are on public display; the British Museum has only 1% of its 8 million objects on display in its galleries.[3] This is far from unique, with the basements of most museums already full.[4] Attempts are being made to put more objects online and to build other storage and research facilities, as is the case with the British Museum[5], but this is a herculean task. Putting collections online is certainly one way to open up collections to the wider public but this requires high levels of funding and will take many years, while digitisation is likely to apply to only a small percentage of museum holdings. The task of making public collections more widely available will be all the more of a challenge in light of the dent in both public and private finances caused by the pandemic. Even prior to the pandemic some public galleries in many museums were unable to remain open due to lack of funding.

In view of the vast wealth of treasures housed and often hidden in museums worldwide, the art market, which is enjoying ever greater public exposure, aided by the digital revolution, has a valuable role to play in bringing a love and understanding of culture to the wider public. While many private collectors understandably keep their collections private, until such time as they reappear on the market, others make theirs available either online or in galleries or privately funded museums. Bearing in mind the number of objects available to view in the many public collections, is the private holding of antiquities really such a cause for concern? Moreover, I am concerned that increasingly persistent and public claims for the return of cultural property, either on sale or in private collections, will inevitably lead to less transparency. This cannot be a desirable outcome; there are greater benefits in encouraging a fruitful dialogue and relationships – the role in society of both public and private collectors should be viewed as complementary.

The market

There are many perspectives on how best to protect cultural objects but thirty years in this business has helped me appreciate the cultural mix of those involved in the trade and collecting as well as the diverse opinions on the ethics of a market which, while often stimulating, have not always been productive. Looting still happens, the trade is still blamed. The art trade is more regulated than ever before and this over-simplistic attitude no longer stands up to scrutiny. The time has assuredly come to formulate lasting and workable solutions, with the trade and collectors central to this process. The existence of an antiquities market is real; millions of objects are legally circulating, more than enough to serve the market. This genie cannot be put back in the lamp.

Background

Egyptian gallery, 29 May 2018, Photo by Macmougins, Mougins Museum of Classical Art, Mougins, France. CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

One of the great joys of working in this business has been the rich fusion of people and cultures – both dealers as well as collectors from all over the world. When the centuries-old antiquities trade closed down in many Middle Eastern countries, the people who operated it were displaced, many to Europe, North America and Australia. An antiquities trade continues in Israel, while in some Middle Eastern and European countries it remains legal to privately own antiquities under strict regulation, with collectors buying antiquities in the knowledge they will never be able to re-sell or export their collections, sometimes leading to the enrichment of national collections[6] or to the foundation of private museums[7], which can lead to controversy but also shows bravery on the part of private individuals who feel passionately about bringing cultural objects back to their region.[8]

From Beyond Attica- The Art of Magna Graecia at the Hellenic Museum, Melbourne, Australia. Loaned by the Koumantitakis Family.

With ancient states and borders often bearing little relation to the countries and people living in those localities today, and with the diaspora of many cultures from these ancient lands living all over the world, it is understandable why many of these communities want to be able to see their culture in the country where they now live. The Greek diaspora in Australia are a long way from their ancestral lands, but

Australians of Greek ancestry have funded and founded the Hellenic Museum in Melbourne[9], which houses a mixture of original artefacts acquired on the antiquities market, as well as replicas. Some of the world’s foremost historians on the history of Magna Graecia and particularly on the identification of pottery from that region have been based in Australia. A British collector founded a museum in Mougins, France[10], bringing considerable benefits to the local community and to international scholarship. He acquired these objects on the antiquities market.

Terms: antiquities, cultural goods, legitimate, illicit, important, and provenance all lack definition

A Roman coin, Denarius of Carausius, reported to the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) illustrates the irregularities that can most easily enable identification of a specific coin. 3rd C CE. (County of findspot) West Berkshire. Surrey County Council. CCA 2.0 Generic license.

The art trade is divided into different disciplines, of which the antiquities trade is one; “ancient art” is a term used interchangeably with “antiquities”. From the international art market’s perspective, this does not cover all ancient archaeological artefacts but only those artefacts (not including coins) from Egypt, Europe, the Near East and the classical world, from the earliest man-made objects of prehistory up until the fall of the Roman Empire to the Byzantine Period.

The legitimate trade in antiquities makes up less than 0.5% of the global art and antiques market[11] with an estimated global value of €150 million – €200 million.[12] When we read newspaper headlines such as ‘Kapoor’s Assistant Pleads Guilty to Possession of Illicit Antiquities’[13], this has nothing to do with the antiquities trade; instead it refers to what the industry categorises as Asian art. Arms & Armour, Asian art, Islamic & Indian art[14], Ceramics & Glass, Ethnographic, Jewelry, Numismatics and Works of Art are all disciplines in the art trade that can sell items of an archaeological nature. Dealers in these disciplines do not regard themselves as part of the antiquities trade and the antiquities trade do not regard those disciplines as part of their trade.

Low value antique glass fragment. Private collection.

While governments, academics, journalists and bloggers call all archaeological artefacts “antiquities”, their definitions do not mirror how the art market operates and this causes issues with data, perception and, importantly, the message doesn’t always get through to areas of the market it needs to. In fact, the inconsistency among definitions of antiquities worldwide is an issue academics and archaeologists struggle with too.[15]

[Ed. Outside of the UK and EU, the term “antiquity” is often used by the market and collectors in reference to any ancient object; under many countries’ heritage laws, an “antiquity” can be any object subject to that country’s heritage laws, being an object more than 100 years old, and in some cases only over 50 years old, while in others it refers to an object more than 1000 years of age. The markets in antique cultural goods of other types are also minuscule compared to contemporary and modern art.]

Anatomy of a horse, manuscript page, Egypt 15th century. University Library, Istanbul.

Most data reporting refers to “cultural goods”, “cultural heritage” or “cultural property”, which contain a wide array of goods. There is a lack of consistency and a lack of understanding in international law, with different understandings in different languages and under different legal regimes.[16] In addition, these terms do not meet the UNDROIT[17] or UNESCO[18] definition that an object must be “of importance”, which means different things to different people. Is every single ancient artefact to be regarded as important regardless of rarity or quality?[19]

The term “illicit” means different things to different people – an object legitimately on the market is called illicit by some on moral rather than legal grounds, but with no clear definition of the term. Some regard any object that at any time left its country of origin without appropriate documentation as illicit, regardless of when this took place and regardless of national laws or whether it is legally circulating on the market. It creates the impression that the antiquities market is saturated with artefacts which are not legally on the market, which is not the case.

When the trade talks about “provenance”, it refers to the collecting history of an object. Antiquities have been collected for hundreds of years, with some collections forming the basis of public museums. Meanwhile if archaeologists talk of provenance, they refer to the exact find spot of an object, something that is rarely known for privately owned antiquities.

Academic relations with the trade and the question of provenance

There is little understanding of the mutually beneficial relationship between the trade, academics and the museum sector. Such relationships matter to us, although in the past 25 years there has been increasing disapproval to the point where many academics are actively discouraged from fraternising with the trade, and not just the antiquities trade but the art market more widely. It can only be beneficial to have others, who are open and not afraid, to have constructive relationships with the trade.

Egyptian glazed steatite bowl, Bolton Museum, Bolton, UK.

Bolton Museum in the UK was a recent beneficiary of such collaboration when a long lost section of an Egyptian glazed steatite dish, dating from the New Kingdom, was spotted by an Egyptologist who was invited to preview objects shortly before it was offered for sale at auction. The Egyptologist knew the other part of the dish from his days curating antiquities at the Bolton Museum. Thanks to private donors, including those within the trade, the two parts of the dish were reunited and are now on display at Bolton Museum.[20]

In an article reflecting on The Illicit Trade Research Centre (1996-2007)[21], Dr Neil Brodie says that:

“Histories of archaeology are, in effect, histories of this process of purification, from antiquarianism to science. But once it became non-archaeology, the antiquities market ceased to be a legitimate object of archaeological reflection or research, and became instead an object of archaeological ignorance and fear—the non-archaeological other. The separation of archaeology from the antiquities market has now become institutionalized…..”[22]

The study of ancient coins has primarily been outside of archaeological context. Major research has been done by collectors and dealers rather than archaeologists. This silver drachm of a bearded male head wearing a crested ‘Corinthian’ helmet was minted in Judea in the 4th C BCE. Published in the first catalog of the British Museum of coin and medal collections by Taylor Combe, Keeper of Antiquities, in 1814. © Trustees of the British Museum.

It has never been in the interests of the trade to separate the objects from academic scholarship; this has been driven by academics and not by the trade. The Brodie article acknowledges that “while academic archaeology has attempted to insulate itself from entanglement with the antiquities market, it has failed.”[23] An article about Cypriot antiquities from the Desmond Morris collection, with the sub-title “orphan artefacts and reconstructed provenances”, clarifies the position of many archaeologists in saying that:

“reconstructed provenance does not fulfil the criteria of archaeological context (placement in the tomb, association with other artefacts…); from a scientific point of view it is still orphan. Moreover, beyond ethical concerns, orphan artefacts with a reconstructed provenance raise scientific issues………. is it scientifically sound to use an object with presumed reconstructed provenance in a study ……. together with other artefacts of secure provenance?”[24]

Collectors and dealers tend to hold a very different view. Each object can tell us something about the culture and people who created it – it has value in all senses of the word. It strikes me and many colleagues in the trade that if archaeologists see so little value in an object once it is out of its archaeological context, then those many hundreds of thousands of objects already out of the ground and circulating on the market have no intrinsic archaeological value and should be allowed to continue to circulate without bringing the opprobrium of academics and governments. There must be a way to record, then to move on and put greater resources into protecting cultural objects in situ along with archaeological sites and monuments.

Many academics who have researched unprovenanced or “unacceptably provenanced antiquities” are often criticised, which is discussed in the Brodie article. Unfortunately, the past twenty-five years have seen a decline in relations between the trade and many academics to the detriment of scholarship, understanding and transparency. It doesn’t have to be this way.

“Orphan” antiquities and provenance research

Saleroom of the Antiquities Service in the Cairo Museum, 1960s. Source International Association of Dealers in Ancient Art (IADAA).

The past ten years have seen a seismic change in how the antiquities market operates, with a much greater emphasis on due diligence, with auction houses and dealers now focusing even greater attention on establishing provenance as best they can. The lack of evidence of provenance cuts to the heart of the problem for the trade. It’s hard to get away from the fact that generally there has been no legal obligation to keep business records beyond 7 to 10 years and for private buyers there is no legal obligation to keep any paperwork at all. Consequently, there are millions of objects legally in circulation without much or any paperwork. These are referred to as “orphan” objects.

When I started out in my career, provenance was only listed in a catalogue if it had belonged to somebody of some importance and this applied to relatively few objects on the market. Unfortunately over the years even this information has often been lost, which is why a dealer’s name or a past auction is often used as provenance. It is really tragic to have lost such information but research does bring some success in piecing together stories and this inevitably enhances an object’s value. In short, good provenance is good for business while insufficient provenance frequently renders an object either unsaleable or has a detrimental effect on its value.

A significant amount of time is spent by auction house specialists and dealers in researching provenance, which can vary from talking to the owner or their descendants, searching databases and visiting libraries, to consulting academics wherever possible, to leafing through old auction catalogues, checking insurance schedules and other documents including receipts, old letters and photographs – this is not an exhaustive list and can be a painstaking and frustrating process as I know only too well from experience. It is important to use one’s judgement and instincts when assessing all available information.

Photograph of two pages from the Register of the Sale Room of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. Università degli Studi di Milano, Eg. Arch. & Lib., Bothmer Collection. Plate 1, Forming Material Egypt: Proceedings of the International Conference, London, 20-21 May, 2013, Patrizia Piacentini, “The antiquities path: from the Sale Room of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, through dealers, to private and public collections. A work in progress. EDAL IV, 2013/2014.

Increasingly dealers and auction houses contact each other to try and establish previous ownership history but this is highly problematic. There is GDPR[25] to consider, combined with differing non-EU national compliance regulations. In the United States, the Jenack vs Rabizadeh ruling[26] set a legal precedent at an appeal court hearing in 2013 where, under New York State law, covering the world’s biggest art market, it was ruled that an auction house cannot be forced to disclose the identity of a consignor. However, changes now coming into force under the 5th Anti-Money Laundering Directive (5AMLD)[27] – already law in the UK and being implemented in EU Member States – may affect this to a degree, although buyers will still not be entitled to know the identity of the seller under this Directive because of conflicting legal rights regarding personal data. The situation is set to change in the United States with the expansion of anti-money laundering laws which will include “dealers in antiquities” under the Bank Secrecy Act.[28]

Members of the trade increasingly have to rely on the goodwill and co-operation of trade competitors to contact their clients or former clients all over the world, often with a language barrier to compound this difficulty. Many clients are no longer contactable, let alone alive, and memories fade with age or illness, while objects from deceased individual’s estates seldom come with any information. There are often legal as well as cultural reasons why initials instead of a name are given as a provenance.

Showcase on the first floor of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, probably 1913. Università degli Studi di Milano, Eg. Arch. & Lib., Varille Collection. Plate 23, Piacentini. “When the Museum moved to Midan Ismailya — now Tahrir, in the first years of the Twentieth century, the Sale Room was located in room 56 of the ground floor, accessible from the western entrance…

(pls xvii-xviii). Id. at 116.

It’s worth bearing in mind that auction houses with specialist antiquities departments tend to hold auctions twice a year, with some other smaller houses holding them up to four times a year, leaving limited time to conduct research. While dealers have more discretion in how long they choose to spend researching an object, their income is predicated on selling objects and ultimately a decision about how extensive the provenance research should be will be influenced by value as well as other factors.

It’s important to address whether it’s practical to expect the same amount of due diligence to be conducted on an Egyptian bead, an arrowhead or an ancient seal worth less than €500 as on a marble sculpture of Aphrodite worth €50,000. Should a non-professional be held to the same standards as a dealer when buying cultural property? The antiquities market is not the exclusive domain of the rich and in fact is one of the areas of the art market where it’s possible to buy something ancient for less than €100. Yet the trade is now expected by some to produce documentary evidence that an object left its country of origin legally or to provide proof it was acquired before 1970 or 2000 when there were no legal requirements to keep any documents and the object might have negligible commercial value.

It’s worth reflecting on what each of us owns – perhaps some art and antiques – do you have any documentation proving it’s yours or when and where you acquired it? Do you have receipts proving an unbroken line of legal ownership? If you acquired something as a gift or by inheritance, how likely are you to have the receipt let alone any other documentation back to the time the object was first made or painted? Should anyone else be able to reclaim it from you if you acquired it in good faith and under what circumstances should you receive compensation? This is the reason why most countries have statutes of limitations in their property laws, which should be respected.

For the millions of antiquities in private collections which have been circulating for decades or centuries, owners will face the same difficulties. While many objects are turned down by the antiquities trade if they do not have acceptable provenance, a solution must be found for the millions of “orphan” objects; these are objects in circulation but without sufficient paperwork. This does not mean they are illegally on the market – on the contrary, for most of them legal statutes of limitation have long since passed. You don’t have to like the trade or agree with it, in order to recognise this truth.

The 2000 date

A 1955 Cyprus export license lists a red polished bowl with white slip, a Roman cooking pot, and a plain white Hellenistic jug, and an Iron Age painted jug. No further descriptions or measurements are included.

For the three most prominent auction houses selling antiquities, the year 2000 is often now used as a date before which evidence of provenance must be provided, although this is not a legal requirement and is an arbitrary date. It is fair to say the auction houses and elements of the trade started to ask for provenance information for antiquities in a more concerted way around 2000, but it was not until at least 2010 that this practice became more universally adopted. The date of 2000 has been used as an unofficial cut-off date since about 2013 and the Art Loss Register (ALR) applies this date rigorously when applicants request an ALR certificate to confirm an item does not appear on a stolen art database. Often information on provenance provided is not deemed sufficiently robust and applications are rejected.

Unfortunately, when a date is retroactively applied it inevitably causes problems and has contributed to creating hundreds of thousands of “orphan” antiquities that have become difficult to sell with the principal auction houses. Without a 2000 provenance, the ALR will not search their databases to confirm whether or not an object appears on a stolen art database; their assumption seems to be that without a provable provenance dating back to 2000 the object is somehow tainted. Unfortunately their decision can taint a previously untainted object by refusing to check it and ironically it means if an object does appear on a stolen art database it will be more difficult to establish. Fortunately the trade can search the INTERPOL database of stolen cultural property, which is proving to be a helpful tool in carrying out due diligence.

A 1975 Cyprus export license has even less information: one Roman glass bottle. Credit Joanna van der Lande.

With difficulty in obtaining provable provenance information back to 2000, how much more difficult or impossible is it to obtain provenance information back to 1993, which is the date of the European Council Directive 1993/7/EEC on the Return of Cultural Objects Unlawfully removed from the Territory of a Member State[29], or to April 1972 when the 1970 UNESCO Convention[30] came into force in those few countries that ratified it early on?

Export Licences from source countries – how useful are they?

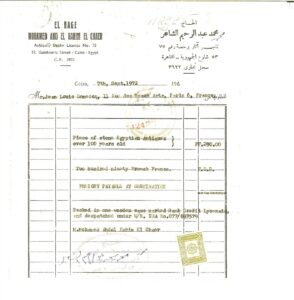

Export Licences from source countries are rarely found and in any event should not be regarded as the great panacea. With no identifying photographs, often no individual description, seldom any measurements and usually a sheet listing unidentifiable objects, it’s almost always impossible to link them with objects currently in circulation.

In Egypt, it was legal to export antiquities under licence until 1983. There was a thriving trade with over 100 licensed dealers in Cairo and the highest known licence No. 127 was still active in the early 1980s.[31] In addition Egyptologists became key agents to collectors and museums who could buy directly from the Director of the Antiquities Service, while the Egyptian Museum in Cairo operated a saleroom from 1888 until the late 1960s.

When it came to export licences, this was controlled by a tax paid and invoices stamped with crates officially sealed but not always inspected. The licence as such was not kept with exported items, and the invoices rarely survived, or where they did were almost never detailed enough to identify the objects they listed with absolute certainty. They often simply listed a numbered quantity of objects on a single line, such as “49 statues”. There was no requirement for the buyer to retain paperwork and there were no photographs, so how is it possible now to link these invoices with objects in circulation?

Egypt Export Permit 1972, issued by licensed dealer El Hage-Mohamed Abd El Rahim El Chaer. Courtesy International Association of Dealers in Ancient Art.

In Lebanon an export licence could be applied for antiquities up until 1988. The system did not differ much from Egypt, with official stamps on invoices listing multiple items now impossible to identify and without photographs. The crates were officially sealed with no export licence accompanying the exported objects. In Cyprus export licences were issued until at least 1980 and some objects had lead export tags attached to them as well, though both tags and licence rarely survive.

When an artwork is exported from the UK or the EU, the export licence does not remain with the exported item. In France a passport can remain with an item but only applies to objects above a specific value threshold and for certain types of cultural property. Paper passports and export licences, where they do exist, are not likely to stay with an object for the next 100 years and beyond.

If the documentation is available, we are only too happy to use it, but in reality documentation that might satisfy the trade’s critics seldom exists; if it does, it lacks any meaningful information which could be matched to an object. Then all it takes is for a source country to cry: “fake documentation”, something no-one can verify and is likely to lead to the authorities confiscating the object. I do not seek to excuse the activities of the trade over the years, but the thorny issue of evidence of provenance needs to be addressed pragmatically, or legitimate trade will become impossible.

END OF PART 1

Read part 2 of The Antiquities Trade: A reflection on the last 25 years, which covers archives, transparency and changing practices, fighting crime, false data, seizures, and the internet.

Read part 3 of The Antiquities Trade: A reflection on the last 25 years, which covers the law, European Union and U.S. developments, art fair seizures, legal trade, orphans and fair compensation, and the way forward.

Author’s Note: I thank UNIDROIT and its Principal Legal Officer & Treaty Depositary, Marina Schneider, for inviting me to present this paper for publication and contribute to the Conference celebrating the 25th Anniversary of the UNIDROIT Convention.

– Joanna van der Lande, Chairman, Antiquities Dealers’ Association

[1] The collecting of antiquities formed part of Cabinets of Curiosity, in both princely and private collections on the Continent then in England centuries ago. They were frequently well ordered and scholarly, within sophisticated settings, long before independent public institutions came into being. Johann Zoffany’s painting of Charles Townley (1737-1805) with his sculpture collection in the library at Park Street, Westminster from 1782, typifies some of these private collections; with his sold to the British Museum in the years following his death. (https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/charles-townley-and-friends-in-his-library-at-park-street-westminster-151327) The 19th Century saw a flourishing of public institutions with their foundations in the philosophy and science of collecting, rooted in the private collections which had abounded in the preceding centuries. The Sir John Soane’s Museum in London was established as a museum in Soane’s lifetime and established as such by an Act of Parliament in 1833, to come into effect on his death in 1837. The requirement was that No.13 Lincoln’s Inn Fields should remain as it was at the time of his death, which it largely has and provides an insight into the breadth and quantity of objects held by just one collector but which was replicated in a multitude of settings both on the Continent and in the British Isles.

[2] “Direct examples of collection building were also offered by many records demonstrating Roman obsession with Greek antiquities. Instances of Greek monumental statuary being appropriated to Roman temples and sanctuaries are well documented” Arthur MacGregor, Curiosity and Enlightenment, New Haven and London 2007, p.2.

[3] British Museum Fact Sheet. https://www.britishmuseum.org/sites/default/files/2019-10/fact_sheet_bm_collection.pdf

[4] The New York Times, Robin Pogrebin, Clean House to Survive? Museums Confront Their Crowded Basements, 12 March 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/03/10/arts/museum-art-quiz.html

[5] The Art Newspaper, Khabir Jahla, British Museum to display hundreds of thousands of archived artefacts in new storage facility, 20 August 2019. https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/british-museum-to-open-new-storage-facility

[6] Ekathimerini, Alexandre Koroxenidis, Private antiquities to go public, 20 January 2003. https://www.ekathimerini.com/11453/article/ekathimerini/life/private-antiquities-to-go-public

[7] ‘Friends since their youth, successful businessmen Jawad Adra, Fida Jdeed, and Badr El-Hage began to ask themselves, “How can we give back?”’ Cultural Property News, Bonnie Povolny, Nabu Museum Opens in Lebanon, Three friends build a museum for antiquities and contemporary art, 24 October 2018. https://culturalpropertynews.org/nabu-museum-opens-in-lebanon/

[8] While critics say some of the artefacts are looted, the founders believe the best way to prevent looting is to encourage collectors to come out into the open. With the collection listed in compliance with the 2016 law which requires collectors in the Lebanon to register their objects with the authorities. “Adra said even before the 2016 decree was passed, he had sent letters to Lebanese, Iraqi and Syrian authorities to inform them of his personal collection, and that he remains open to cooperating with Iraqi authorities to return some or all of the objects.” “Come at our cost, see it, let’s discuss it and let’s sign a protocol.” Abby Sewell, Museum tangled in debate over heritage, 11 April 2019. https://www.dailystar.com.lb/News/Lebanon-News/2019/Apr-11/480893-museum-tangled-in-debate-over-heritage.ashx

[9] Hellenic Museum, Melbourne. https://www.hellenic.org.au/

[10] Mougins Museum. https://www.mouginsmusee.com/en/static/the-mougins-classical-art-museum

[11] The Art Basel and UBS Global Art Market Report 2020, which reflects the figures for 2019, estimates the Global sales of art and antiques to have been approximately $64.1billion. https://d2u3kfwd92fzu7.cloudfront.net/The_Art_Market_2020-1.pdf

[12] Research undertaken by IADAA (the International Association of Dealers in Ancient Art) into the legitimate global trade in antiquities, undertaken in 2013, estimated its value at between €150 million and €200 million. While an American non-profit global policy think tank recently published the RAND Corporation Report Tracking and Disrupting the Illicit Antiquities Trade with Open-Source Data (June 2020), p.84, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2706.html estimates both the legitimate and illicit market for all antiquities as ‘a few hundred million dollars annually’. The RAND Corporation Report includes coins and more extensive data on what is sold via the online selling platforms. In spite of the intervening years and the broader range of objects, their findings are very close to those of IADAA.

[13] Centre for Art Law, Angela Selleck, Kapoor’s Assistant Pleads Guilty to Possession of Illicit Antiquities, 6 January 2014. https://itsartlaw.org/2014/01/06/kapoors-assistant-pleads-guilty-to-possession-of-illicit-antiquities/

[14] In the article it refers to “antiquity smuggling” when the market would identify these as tiles from the Islamic art market, The Guardian, Mark Brown, British Museum to repatriate ancient tiles smuggled into UK in a suitcase, 11 October 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2020/oct/11/british-museum-to-repatriate-ancient-tiles-smuggled-into-uk-in-a-suitcase

[16] IRRC, Vol.86 , no.854, Manlio Frigo, Cultural property v. cultural heritage: A “battle of concepts” in international law?, June 2004, p.377. https://international-review.icrc.org/sites/default/files/854.pdf

[17] UNIDROIT Convention on Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Objects, Rome 1995, Article 2. https://www.unidroit.org/instruments/cultural-property/1995-convention

[18] The UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property 1970, Article 2. http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=13039&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html

[19] “A large segment of the public labors under the delusion that all objects of a certain age, regardless of their rarity, quality, or aesthetic appeal, are priceless. There is also an assumption that museums worldwide are somehow deprived of this material by private collectors and that every scrap of it must be held and maintained in perpetuity in a public institution.” International Journal of Cultural Property (2019) 26:227–238, Randall Hixenbaugh, The Current State of the Antiquities Trade: An Art Dealer’s Perspective, p.229. https://iadaa.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Hixenbaugh-current_state_of_the_antiquities_trade_an_art_dealers_perspective-09-2019.pdf

[20] Apollo Magazine, Tom Hardwick, The Victorian collectors who loved art from Ancient Egypt, 25 January 2020. https://www.apollo-magazine.com/bolton-ancient-egypt-museums-collecting/?fbclid=IwAR0Ks3w6-kvanZQpwkjHMekCpKM-AHHWPTzq4kmL_FfgUxbp8Zi-wMP69HI

[21] The Illicit Antiquities Research Centre (IARC), founded in 1996, was part of the McDonald Institute of Archaeological Research at Cambridge University; it changed the pace and tempo of the criticisms leveled at the antiquities trade. It was established to assess the true scale of the illicit trade and decided “to communicate a continuous stream of information and argumentation through whatever channels were available” (Brodie, p.3), from producing publications to press stories. IARC survived until 2007 when it ran out of funding. During that period, it was influential, albeit a thorn in the side to the trade, and had political clout because the Director of the McDonald Institute was Lord Renfrew of Kaimsthorn, a member of the House of Lords.

[22] Neil Brodie, The Illicit Antiquities Research Centre: Afterthoughts and Aftermaths, p.7. https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:eb05ca26-3597-4f4d-958b-c9a7b3c74c5c/download_file?file_format=pdf&safe_filename=The%2BIllicit%2BAntiquities%2BResearch%2BCentre%2Bafterthoughts%2Band%2Baftermaths.pdf&type_of_work=Book+section

[23] Brodie, p.8.

[24] Netcher, Social Platform for Cultural Heritage, From Cyprus to London and back again: Focus on the Desmond Morris collection of Cypriot antiquities. 3 September 2020.

[25] Official Journal of the European Union, text for General Data Protection Regulation – Regulation (EU) 2016/679 27 April 2016. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32016R0679&from=EN

[26] Art Law Report, Jenack v. Rabidazeh Decision Reversed. https://blog.sullivanlaw.com/artlawreport/2013/12/17/jenack-v-rabidazeh-decision-reversed-auction-sellers-and-consignors-can-remain-anonymous/

[27] Official Journal of the European Union, Directive (EU) 2018/843, 30 May 2018. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32018L0843&from=EN

[28] New York Times, Zachary Small, Congress Poised to Apply Banking Regulations to the Antiquities Market,

1 January 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/01/arts/design/antiquities-market-regulation.html

[29] Official Journal of the European Communities, Council Directive 93/7/EEC, 15 March 1993. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:31993L0007&from=EN

[30] Text on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property 1970. http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=13039&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html

[31] Fredrik Hagen and Kim Ryholt conducted a fascinating study of the Antiquities trade in Egypt based on the H.O. Lange papers and provides a valuable though incomplete insight into how the trade functioned between 1880-1930. See Scientia Danica. Series H, Humanistica, 4.vol.8, Fredrik Hagen and Kim Ryholt: The Antiquities Trade in Egypt 1880-1930. The H.O. Lange Papers, December 2015. https://www.royalacademy.dk/en/Publikationer/Scientia-Danica/Series-H4/H4_8_The-Antiquities-Trade-in-Egypt

Giovanni Paolo Panini, The philosopher Diogenes throwing down his bowl, Photo by Macmougins, Mougins Museum of Classical Art, Mougins, France. CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

Giovanni Paolo Panini, The philosopher Diogenes throwing down his bowl, Photo by Macmougins, Mougins Museum of Classical Art, Mougins, France. CCA-SA 4.0 International license.