Committee for Cultural Policy and Global Heritage Alliance, Written Testimony submitted to Cultural Property Advisory Committee, Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, U.S. Department of State, on the Proposed Memorandum of Understanding Between the United States of America and the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan

To Chairman Sabloff and the Members of the Cultural Property Advisory Committee to the President:

The Committee for Cultural Policy (CCP)[1] is an educational and policy research organization that supports the preservation and public appreciation of the art of ancient and indigenous cultures.

CCP supports policies that enable the lawful collection, exhibition, and global circulation of artworks and that preserve artifacts and archaeological sites through funding for site protection. CCP deplores the destruction of archaeological sites and monuments and encourage policies enabling safe harbor in international museums for at-risk objects from countries in crisis. CCP defends uncensored academic research and urges funding for museum development around the world. CCP believes that communication through artistic exchange is beneficial for international understanding and that the protection and preservation of art is the responsibility and duty of all humankind.

Global Heritage Alliance (GHA)[2] advocates for policies that will restore balance in U.S. government policy in order to foster appreciation of ancient and indigenous cultures and the preservation of their artifacts for the education and enjoyment of the American public. GHA supports policies that facilitate lawful trade in cultural artifacts, and promotes responsible collecting and stewardship of archaeological and ethnological objects.

The Committee for Cultural Policy and Global Heritage Alliance jointly submit this testimony on the Proposed Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) for the imposition of import restrictions between the United States and the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan.

The Jordanian Request Fails to Establish the Criteria Set By Congress

Both the Committee for Cultural Policy and Global Heritage Alliance support the Congressionally mandated application of the 1983 Cultural Property Implementation Act (CPIA).[3] However, the Committee for Cultural Policy and Global Heritage Alliance concur that the request by the Government of Jordan (Jordanian Request) fails to meet the criteria under the Act. Further, both object strongly to the State Department’s failure to publish a complete text of the request; a publicly available statement of the evidence meeting the statutory requirements is necessary in order to determine whether the request actually meets the criteria set by Congress in the CPIA.

Based upon the U.S. Department of State (the “Public Summary”), the Jordanian Request fails to provide sufficient information on current looting or other threats to heritage in order to meet any of the statutory requirements of the Cultural Property Implementation Act.

The Jordanian Request is Excessively Broad: It Applies to All Antiques and Antiquities from Prehistory to 1750 C.E. Without Showing that Looting is Happening Today

The Public Summary of the Jordanian Request calls for a broad ban on all antique and ancient objects from Jordan from the Paleolithic (1,500,000 years to 20,000 years ago) through 1750 C.E., roughly correlating to the later Ottoman period. The request is for restrictions on:

“archaeological materials in stone, metal, ceramic and clay, glass, faience and semi-precious stone, mosaic, painting, plaster, textile, basketry, leather, bone, ivory, shell and other organics, as well as human remains.”

Instead of substantiating the claim that all the above classes of objects are subject to looting for a U.S. market, the Public Summary of the Jordanian Request refers generally to a longstanding trade in the 19th and early 20th centuries in Biblical and Holy Land artifacts. It blandly states that “100 sites with Islamic period occupations have been affected by looting,” but does not even provide estimates or general timeframes for when that looting took place. It acknowledges that “it is challenging to determine” statistics on looting in Jordan.

Regrettably, the State Department has routinely executed blanket agreements that extend to a nation’s entire cultural history.

As James Fitzpatrick has noted,[4]

“on their face, wall-to-wall embargoes fly in the face of Congress’ intent. Congress spoke of archeological objects as limited to “a narrow range of objects…”[5] Import controls would be applied to “objects of significantly rare archeological stature…As for ethnological objects, the Senate Committee said it did not intend import controls to extend to trinkets or to other objects that are common or repetitive or essentially alike in material, design, color or other outstanding characteristics with other objects of the same type…[6]”

This is just such a proposed wall-to-wall embargo. Yet nowhere in the Jordanian Request is there specific information on current looting or on recent U.S. imports of looted examples of any of these materials.

Instead, the Jordanian Request mentions looting that took place between 1934 and 1996, and looting in the 1990s generally – that is, over twenty years ago. It fails to even attempt to provide evidence that the vast range of materials for which import restriction are requested is currently subject to looting in Jordan, and does not meet the requirements set by Congress in the Cultural Property Implementation Act. It has thus failed to satisfy the determinant required by 19 U.S.C. § 2602(a)(1)(A) that the specific items of cultural patrimony for which import restrictions are sought are in jeopardy from pillage, or that pillaged artifacts are entering the U.S.

Mandatory statutory determinations should be met based on evidence and facts, not speculation. The Jordanian Request is completely inadequate to satisfy the determinants required by the Cultural Property Implementation Act.

Both the Jordan Summary and Public Comments Demonstrate Jordan’s Failure to Protect Sites

Mosaic of the god Oceanus Petra, Jordan. June 2010. Photo Gilles Mairet. Wikimedia Commons.

Clearly, the Public Summary of the Jordanian Request fails to show that Jordan has taken steps to adequately protect its ancient sites. It has thus failed to satisfy the determinant required by 19 U.S.C. § 2602(a)(1)(B) that the State Party has taken measures consistent with the Convention to protect its cultural patrimony.

It appears, therefore, that absent evidence supplied by the requesting country, the CPAC will rely on statements submitted to it by the public.

Yet these statements either undercut the argument that Jordan meets the criteria for import restrictions by recognizing that Jordanian authorities are not taking steps to protect sites, or fail to acknowledge that the movement of antiquities from Jordan to Israel and their subsequent illegal sale as Israeli antiquities by Israeli dealers has ended with the very restrictive and strictly enforced provisions of new Israeli laws and regulations on the trade.

For an example of the first, submissions from archaeologists working in Jordan to this committee state that looting takes place in a permissive atmosphere, at times with the collusion of the authorities. To quote from the letter submitted by Dr. Gary Rollefson to this committee on March 22, 2019 regarding excavations conducted by him in the Black Desert since 2008:

“As an example, the week before we were scheduled to begin the excavation of a 5,000-year-old tomb, looters trashed it (Fig. 2); while the looter worked, members of the Badia Police station brought him tea! Our DoA representative spoke to the Badia Police (they didn’t know looting was illegal) and to visitors (who were in the desert to loot sites), discussing with them our excavations, and telling them that it was illegal to dig without a permit. Unfortunately, these were probably the same people who would return to destroy the remarkably well-preserved Neolithic buildings we had been excavating in the Black Desert (see Figure 3 [undated])..”

Dr. Bert DeVries also wrote is his submission to CPAC that police and site guards are not doing their jobs:

“…The day included a very frank presentation of site security issues by the Dept of antiquities regional Director, Dr. Ismaeel Melhem. He spoke in Arabic, with all the site guards present, and laid out the socio-economic issues – poverty and unemployment – that have made looting endemic, and also the lack of power local guards have as members to the community without police authority to arrest. It also became clear that these local guards are so afraid of the looters, that they do not patrol the site from sunset to sunrise, the very period when 99% of looting activity takes place. The speech was translated into English for Mr. by UJAP, site supervisor Muaffaq Hazza. (I, Muaffaq and my staff feel that there is an extent of liaison between some of the guards and some of the looters.)”

If the police do not know that looting is illegal, and are bringing looters tea, the Jordanian authorities are clearly failing to enforce Jordanian laws and protecting cultural property as the CPIA requires.

Smuggling Antiquities to the Israeli Market is No Longer Viable

Dr. Morag Kersel’s argument for imposing import restrictions on Jordanian imports in her letter to CPAC submitted March 22, 2019,[7] places great weight on the movement of antiquities from Jordan through illegal sales from antiquities dealers in Israel, perhaps because there are not U.S. sales of Jordanian objects to point to. She does not mention that new Israeli regulations requiring online, registered inventories in Israel now make introducing smuggled antiquities into the Israeli market virtually impossible.

Regulations require antiquities dealers to document their entire commercial inventory through an online inventory management program. The new regulations require computerized documentation, including photographs, to be uploaded into a database which is managed by the Israel’s Antiquities Authority. Every ancient artifact has an individual commercial identification number and registered photograph. The program allows computer tracking of exchanges between dealers and issue of export licenses.

In August and September of 2016, Israel’s Antiquities Authority (IAA) moved to close down several licensed dealers for failure to complete inventories required under new laws upheld by Israel’s High Court in January 2016. One dealer had 100 boxes of antiquities seized by the IAA, solely for failing to register them timely. Historically, Israel permitted a limited trade in antiquities, in which objects found after passage of the Antiquities Law of 1978 became state property, but registered dealers were allowed to continue to sell old stock. The system was widely considered susceptible to cheating, as items were sold and replaced with other similar items in the dealers’ handwritten books. Between fifty and sixty registered dealers, many of them of Palestinian background, operated legally in Israel.[8]

The loopholes cited by Dr. Kersel, which allowed trade in smuggled antiquities, have been closed.

The Jordan Summary Shows That Jordan Prohibits All Trade on Paper, But Fails to Halt Jordanian Domestic Trade in The Same Items It Seeks to Prevent From U.S. Import

The Public Summary of the Jordanian Request fails to show that Jordan has taken steps to halt sales within Jordan to tourists of the coins, trinkets, and low value items sold openly at tourist-frequented ruins such as at Petra. Jordan has a broad general law placing all immovable property under the ownership of the government of Jordan, and requiring approval of the Cabinet for the export of movable antiquities outside the Kingdom.[9]

However, Jordan has not closed down the domestic and tourist trade in its generally low value antique objects and there is an annual coin show held in Amman at which foreign and domestic buyers may acquire coins. In “International collectors flock to Amman for stamp, coin fair,” The Jordan Times, July 28, 2016, Sawsan Tabazah described how the mayor of Amman inaugurated an exhibition at the fair, which was organized by the Jordan Philatelic and Numismatic Society in cooperation with the Greater Amman Municipality, the Ministry of Culture, Jordan Post and Petra Travel and Tourism Co. The article further states:

“Collectors from Jordan, the Arabian Gulf, Iraq, India, the Netherlands and the US are sharing currency and stamps collected from all over the world at the fair, said Ibrahim Arnaout,”… and “Tariq, a Jordanian collector, said coins from the Sasanian Empire, the Byzantine Empire and the Roman Empire were on display.” A Saudi Arabian collector noted that, “items in his collection are worth between JD1 and JD20,000.”[10]

Nor does the Jordan Summary provide information on whether Jordan prohibits or licenses metal detectorists. Such actions would appear to be necessary in order to meet the requirements under both 19 U.S.C. § 2602(a)(1)(B) and 19 U.S.C. § 2602(a)(1)(C)(ii), which conditions import restrictions on the fact that remedies less drastic are not available.

Jordan Does Not Enforce Its Own Laws Requiring Documentation By Private Owners

Jordanian law requires that “whoever owns or has possession of any movable antiquities shall provide the Department a list of the objects specifying their quantity and including pictures and other identifying details for each object, including a brief description. The Department may, if it deems proper, register these objects.[11] The Public Summary of the Jordanian Request does not even mention a register of such objects, if it exists.

The Jordanian Request Does Not Establish That There Is A U.S. Market For Jordanian Artifacts

The Public Summary fails to show that the United States is a significant market for recently looted Jordanian antiquities (in fact, it fails to show that there is any significant market today for recently looted Jordanian antiquities anywhere), and that U.S. import restrictions will have a significant effect in preventing current looting in Jordan, if such exists.

The Public Summary notes that a single gallery in Colorado has offered a single object actually identified as Jordanian for sale in 2017. (This is the same Artemis Gallery that seems to be referenced in every new request for import restrictions, as it is one of the very, very few U.S. galleries that still auctions antiquities, the majority of auction venues having decided that it is too much trouble for too little money to continue.)

I spoke with Artemis Gallery owner Bob Dodge, who told me that this Nabatean object was one of only two objects from Jordan that his gallery had sold in the last twenty years, stating that his gallery buys its “Holy Land” antiquities primarily from licensed galleries in Israel, or else from old U.S. collections (made since the early 19th century and collected by Americans on tour to the region long before today’s national boundaries existed). The only other Jordanian object the gallery has had is a small redware cup, which is priced under $1100 and has twice failed to sell. The Nabatean bronze was published in 2006 by another U.S. gallery, which had purchased it from a gallery in France. The Nabatean bronze, which the Jordanian Summary describes as selling for between $15,000 and $25,000, actually sold for just above $5000. Mr. Dodge stated that his gallery does not purchase objects from any country that have recently entered the U.S., holding to the 20-year safe harbor provisions of the CPIA as a standard.

Obviously, the sale of the single Nabatean bronze in 2017 does not demonstrate that the U.S. has a significant market in Jordanian antiquities, much less potentially looted Jordanian antiquities. Section 303(a)(1)(C) of the CPIA states that U.S. import restrictions may be implemented only if:

“the application of the import restrictions set forth in section 307 with respect to archaeological or ethnological material of the State Party, if applied in concert with similar restrictions implemented, or to be implemented within a reasonable period of time, by those nations (whether or not State Parties individually having a significant import trade in such material, would be of substantial benefit in deterring a serious situation of pillage…”

Thus, the request has failed to show that U.S. import restrictions, in concert with similar restrictions implemented, or to be implemented within a reasonable period of time, by those nations (whether or not State Parties) individually having a significant import trade in such material, would be of substantial benefit in deterring a serious situation of pillage. Jordan has failed to satisfy the determinant required by 19 U.S.C. § 2602(a)(1)(C)(i).

Finally, the statute requires a showing that the application of the import restrictions is consistent with the general interest of the international community in the interchange of cultural property among nations for scientific, cultural, and educational purposes. Jordan has failed to meet even the generous terms under which this committee has interpreted claims that a sufficient number and commitment to museum loans and traveling museum exhibitions sent to the U.S. will compensate for the curtailing of entry of Jordanian art and artifacts to the U.S. market.

Severe Shortage of Museum Loans From Jordan

While the Jordanian government has enabled a number of international archaeological excavations and projects, including U.S. archaeologists, to excavate in Jordan, it has not sent Jordanian international travelling exhibitions to U.S. museums. Archaeologists may benefit from friendly relations between the U.S. State Department and Jordan, but the general U.S. public does not.

Conclusion

Jerash old city with ancient monuments, October 2014, photo Britchi Mirela. Wikimedia Commons.

In sum, both the Public Summary written by the Department of State, and the comments submitted to CPAC in support of a Memorandum of Understanding with Jordan fail to demonstrate that the Jordanian Request meets the criteria set by Congress for an agreement under the CPIA. The committee does not need to be reminded that every one of the statutory criteria must be met in order for the U.S. to implement import restrictions under the Cultural Property Implementation Act.

Imposing import restrictions in defiance of the mandatory requirements of the Cultural Property Implementation Act is not only wrong, it makes a mockery of the law and the eight year legislative process in which Congress balanced the need to protect precious archaeological resources and deter pillage, and at the same time, to ensure that U.S. citizens and U.S. museums had access to global cultural resources. Over time, the scope and duration of import restrictions under the CPIA has expanded to provide for near permanent bans on the import of virtually all cultural items from the prehistoric to the present time from the countries which have sought an agreement under the CPIA. This not only dismisses Congress’s goal of maintaining a rich cultural life and viable economic trade in art in the U.S. It also has failed to heed legitimate Congressional concerns that the 1970 UNESCO Convention would lend itself to exclusively statist rather than internationalist approaches to heritage, and become a victim to nationalist and political goals.

When the CPIA was passed, Congress never indicated that it was in the interests of the United States to block imports of all art and archaeological materials from source countries. Congress contemplated a continuing trade in ancient art except in objects at immediate risk of looting. Nor did Congress state that halting the trade in art was a positive goal. On the contrary, Congress viewed the CPIA as balancing US academic, museum, public and commercial interests by both assisting art source countries to preserve archaeological resources and ensuring the U.S.’s continuing access to international art and antiques through a relatively free flow of art from around the world to the U.S.[12]

As both the Committee for Cultural Policy and Global Heritage Alliance have stated in the past, and doubtless will state again, the Cultural Property Advisory Committee should live by the law that created it, and apply a plain reading to the four determinations it must make . CPAC can follow the dictates of Congress. It can honor and respect the limitations of the law – by not signing a Memorandum of Understanding or imposing excessively broad import restrictions in a situation such as this unmerited request from the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, in an instance in which the facts and the law do not support it.

[1] The Committee for Cultural Policy, POB 4881, Santa Fe, NM 87502. www.culturalpropertynews.org, info@culturalpropertynews.org.

[2] The Global Heritage Alliance. 1015 18lh Street. N.W. Suite 204, Washington, D.C. 20036. http://global-heritage.org/

[3] The Convention on Cultural Property Implementation Act, 19 U.S.C. §§ 2601, et seq.

[4] James F. Fitzpatrick, Falling Short – the Failures in the Administration of the 1983 Cultural Property Law, 2 ABA Sec. Int’l L. 24, 24 (Panel: International Trade in Ancient Art and Archeological Objects Spring Meeting, New York City, Apr. 15, 2010).

[5] Senate Report No. 564, 97th Cong., 2nd Sess. at 4 (1982)

[6] Senate Report No. 564, 97th Cong., 2nd Sess. at 6 (1982)

[7] Letter from Dr. Morag Kersel to the Cultural Property Advisory Committee, dated March 22, 2019, https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=DOS-2019-0004-0004

[8] Ilan Ben Zion, In new crackdown, antiquities authorities tighten noose around dealers, thieves, Times of Israel, 5/16/2016, https://www.timesofisrael.com/in-new-crackdown-antiquities-authorities-tighten-noose-around-dealers-thieves/

[9] Jordanian Law of Antiquities No. 21 of 1988 as amended by Law No. 23 of 2004, Art. 24.

[10] The Jordan Times, July 28, 2018. http://jordantimes.com/news/local/international-collectors-flock-amman-stamp-coin-fair. Last visited March 25, 2019.

[11] Jordanian Law of Antiquities No. 21 of 1988 as amended by Law No. 23 of 2004, Art. 7.

[12] 19 U.S.C. § 2602(a)(1)(A-D) and 19 U.S.C. § 2602(a)(4)

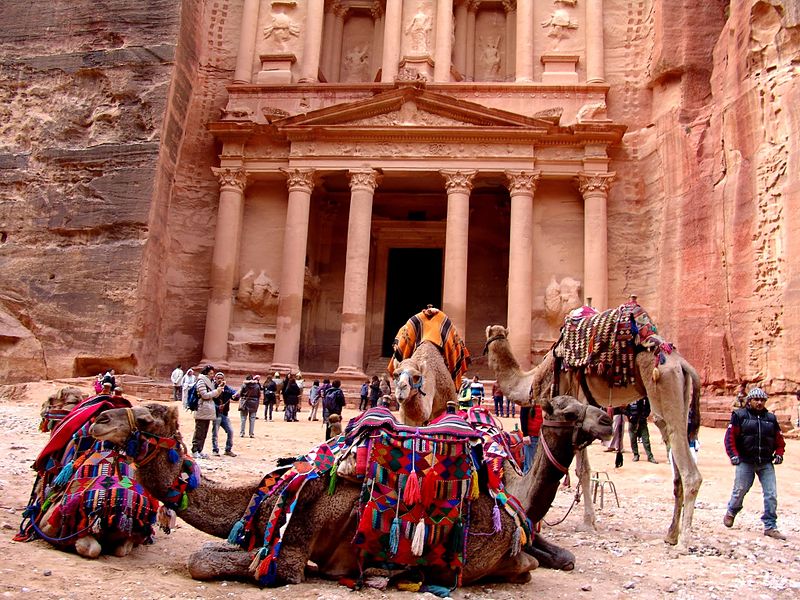

Petra, Jordan, "Tourist attraction," January 4, 2014, photo Leon Petrosyan.

Petra, Jordan, "Tourist attraction," January 4, 2014, photo Leon Petrosyan.