An article posted September 13, 2017 on the website of the National Coalition of Syrian Revolution and Opposition Forces reported that the Directorate of Museums in the Free Idlib Provincial Council plans “to file lawsuits in international courts to recover the looted relics that Assad’s militias stole and smuggled out of Syria.”

Idlib Museum director, Anas Zeidan stated, “the Assad regime militias loot antiquities from the historical sites in the areas under their control to sell them on the black markets.” Plans are in the works to compile a list of missing artifacts for the lawsuit as well as to share with UNESCO.

However, since both the US and the EU have been extremely effective in blocking imports of Syrian antiquities (and Western art dealers have refused to sell them), any missing objects are likely to be found in Middle Eastern countries that surround Syria, and which have political relationships with the Assad regime – or in Middle Eastern or Asian nations that are not as subject to UNESCO’s influence as the West.

A Fractured Region of Many Loyalties

Idlib is located in northwestern Syria, and has been a stronghold of the Syrian resistance over the years. The Idlib Museum is officially one of five museums under the auspices of the General Directorate of Antiquities and Museums of the Syrian Ministry of Culture. However, the town of Idlib is not under Syrian government control. An alliance of anti-government groups formed in January and linked to al-Qaeda, called Hay’et Tahrir al-Sham, currently controls much of Idlib province. (The region has been unstable for years, and in the last week, institutions in Idlib have been under particularly aggressive attack. The UK-based Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (SOHR) said on September 20 that Syrian and Russian jets struck four facilities, including a maternity hospital, in a retaliatory assault. At least four hospitals have been targeted by air strikes in Syria’s northwestern province of Idlib. In August, seven White Helmet medics were killed in an armed attack that resistance forces say may have been intended to harm the image of the Al-Qaeda-linked Nusra front.)

Government Bombings Sparked Looting of Museums by Militias

Virtually every Syrian group, but especially government and government-supported forces are said to have been involved in looting. In spring 2015, Idlib museum workers sealed the collections into underground rooms to protect them from imminent fighting. Within a few days after a coalition of rebel fighters – including Ahrar a-Sham, Jund al-Aqsa and Jabhat a-Nusra – took the city of Idlib, a barrel bomb (from Syrian government or Russian planes) struck the top of a storeroom and exposed its contents.

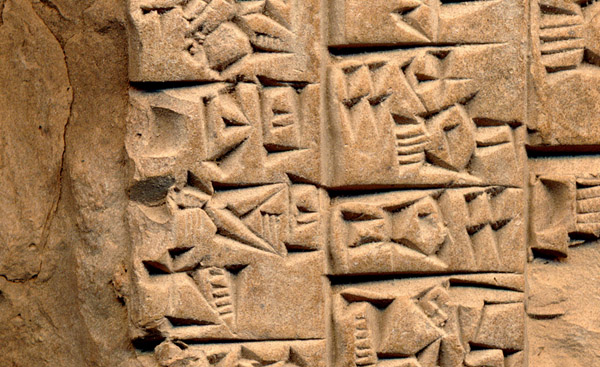

Although museum staffers were not allowed by anti-government forces in to the bomb site, it was reported that the exposed items were taken. Later, in 2016, Syria Direct reported that plastic boxes filled with pottery shards in museum-numbered bags from earlier excavations were seen in photographs taken in a rural headquarters belonging to Jund al-Aqsa in the Idlib region. These were immediately recognized by museum staff as from the museum. Although of no commercial value, the shards were archaeological research materials. It was not known at the time what happened to the boxes of shards, nor what else might have been taken from the museum, despite the collections having been buried and sealed into walled in rooms. Ayman Nubu of the Syrian Idlib Antiquities Center said in 2016 that the items of greatest concern were some 15,000 cuneiform tablets stored at the museum.

http://syriadirect.org/news/some-looted-idlib-national-museum-artifacts-resurface-fate-of-others-a-mystery-amidst-%E2%80%98thriving-black-market-trade%E2%80%99/.

In a History of Pillage, Who Is to Blame?

If an international court were to hear the Idlib Museum’s complaint, the question remains as to how the repatriation issue could be resolved even if the museum was able to successfully sue. The museum’s current claims are against the Syrian government. Yet it is unclear how many times the museum has been pillaged, and by whom. As control of Idlib has shifted between various pro and ant-government forces, it may not be possible to identify the culprits who took items or how they were transferred among forces. Would the same people that looted the items – according to the museum, Syrian government militias – get them back? In this situation of crisis, is there a better argument for Western museums to offer Syrian items “safe harbor,” as multiple governments, including the US, have offered to do?

Study Shows Assad Regime Has Failed to Protect Heritage, Engaged in Looting

The complaint by the Idlib Museum is not the only one about Assad’s troops being chief among Syrian looters. This is old news, though little known, since the Western press is completely focused on claims that ISIS is responsible for looting for profit. A September 2015 Dartmouth-led study published in Near Eastern Archaeology analyzed satellite imagery of nearly 1,300 archaeological sites in Syria, and revealed that the Kurdish YPG, opposition forces and the Syrian regime have also been involved in looting, often in the immediate proximity of Syrian government and YPG troops, who collude in the looting.

The study states that one of the best-known and most chronically looted sites in Syria was Apamea, a large Roman city in Western Syria, where looting with bulldozers reportedly took place on a block-by-block basis with Assad’s Syrian government troops some 200 yards away. The study was headed by Dr. Jesse Casana, Middle East archaeologist and associate professor of Anthropology at Dartmouth. Dr. Casana was also director for remote sensing at ASOR’s Cultural Heritage Initiatives, and is currently directing an archaeological survey in Kurdistan, Iraq.

Dr. Casana stated:

“Most media attention has focused on the spectacles of destruction that ISIS has orchestrated and posted online, and this has led to a widespread misunderstanding that ISIS is the main culprit when it comes to looting of archaeological sites and damage to monuments.”… “Using satellite imagery, our research is able to demonstrate that looting is actually very common across all parts of Syria, and that instances of severe, state-sanctioned looting are occurring in both ISIS-held and Syrian regime areas.”

The Stolen Art Is Not in the West – US and European Dealers, Collectors and Museums Have Opposed Trade in Stolen Art

Calls for repatriation must be directed to countries without the protections – or the anti-looting commitment – of the US and UK. No items looted from Syria have been identified as coming to the US, and very, very few to Europe or the UK. A massive investigation and search operation across 18 European countries in 2016 called Pandora found not a single item looted from the war-torn Middle East. Several thousand items looted or stolen from Syria have been returned to its government by Lebanon, and it appears that looted items are most likely to be found in countries neighboring Syria. It is hoped that the Idlib Museum items were documented while in the museum, in order to ensure identification.

Importantly, the US already has strong laws in place to prevent the import of stolen cultural property from any nation. Any items stolen from the inventory of a museum or church or other institution can be seized and returned under the Cultural Property Implementation Act of 1983. In addition, items stolen from inventory could be seized and returned as goods stolen under the National Stolen Property Act. Such items could never be lawfully sold in the US.

Imports of Cultural Property from Syria Are Already Banned in the US

It is worth repeating that the US Congress has also responded specifically to the issue of Syrian cultural property. Congress passed the Protect and Preserve International Cultural Property Act on May 9, 2016.[note]Authority for the import restrictions are found under 5 U.S.C. 301; 19 U.S.C. 66, 1202 (General Note 3(i), Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (HTSUS)), 1624; Section 12.104k also issued under Pub. L. 114-151, 130 Stat. 369; 19 U.S.C. 2612.[/note] This Act bans the importation of Syrian antiquities. The US Federal Register has published “Import Restrictions Imposed on Archaeological and Ethnological Material of Syria” also known as the Designated List, that identifies all items covered, and was effective August 15, 2016.

No items on the Designated List can be imported into the United States unless Syria issued a permit for export or unless other conditions were met. Items can be temporarily held in the US for their protection under “safe harbor,” at the request of the Syrian government, but must be returned to Syria at its government’s request – i.e. to the Assad regime.

The Syrian Designated List applies to all items exported from Syria on or after March 15, 2011. It covers virtually all items from 1,000,000 BC to 1920 AD. The periods covered are from the Paleolithic, Neolithic, Bronze and Iron Ages, Persian, Greco-Roman, Byzantine, and Islamic until the end of the Ottoman Period. Materials include stone, metal, ceramic, glass, ivory, bone, shell, plaster, stucco, textiles, paper, leather, paintings and drawings, mosaic, and writing.

Regardless of the Idlib Museum’s success in filing an international lawsuit to recover stolen artifacts, it may rest assured that any museum items that came to the US could not be placed on the market. However, there are also questions that go to the larger issue of access to Syrian art and artifacts.

Overbroad Law Hurts Legitimate Collectors, Christians and Jewish Minorities in the Middle East

US laws already ensure that stolen art and artifacts from Syria are not sold in US markets. But there are still questions about the principles of blanket repatriation. Is it right and proper for the US to promote the return of Syrian items belonging to religious and ethnic minorities to the Syrian government? Does it matter that the Syrian government places a low priority on cultural protection, has multiple times knowingly bombed museums, claiming terrorists were hiding there? Does it matter that Syria is a fractured state that has condoned horrific human rights violations against religious and ethnic minorities?

Religious and liturgical objects on the Designated List may not be imported into the US. These specifically include manuscripts, Bible caskets, Kiddush cups and Torah pointers. As it exists today, US law requires that the communal property and personal possessions of religious minorities and refugees fleeing Syria be seized and sent back, and without proof of lawful prior export, Christians and Jews who earlier fled the repressive Syrian regimes might lose these heirlooms if they attempted to bring them into the US.

What about the effect of a too broad law on items that may not even be from Syria? Popularly collected items such as Roman Imperial coins that might conceivably have circulated in Syria are included on the Designated List, and will be seized on import. There is less fear, then, that the Idlib and other museum collections could be unlawfully sold, and more to worry about in a blanket ban that prevents the legitimate possession of religious and other heirlooms by those fleeing the conflict-riven region. There is also concern that because of its breadth, the current US law on Syrian art may become a virtual US ban on import of all Near Eastern objects.

Cuneiform tablet from the Idlib Museum. http://cdli.ucla.edu/collections/syria/idlib_en.html@section=3.html.

Cuneiform tablet from the Idlib Museum. http://cdli.ucla.edu/collections/syria/idlib_en.html@section=3.html.