The Rubin Museum in New York City has opened a truly exceptional exhibition, Faith and Empire-Art and Politics in Tibetan Buddhism, which highlights the dynamic political aspects of the Tibetan artistic tradition, particularly through Sino-Tibetan artistic exchange, from the 7th to the 19th century. The exhibition runs from February 1- July 15, 2019.

Major works of painting, woodblock, sculpture, silver, and silk embroidery, have been gathered for the exhibition from numerous private and public collections. Carlton Rochell, one of the many supporters of the exhibition, said that he was “highly impressed to see individual works from the Cleveland Museum of Art, The Musee Cernuschi, Paris, the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco and the Pritzker Collection in the context of Imperial art commissions in Tibet and China. Many of these works are historically important in this context as they have inscriptions which attribute them to particular aeteliers and time periods.”

The Buddha Amityaus; possibly Chengde (Jehol), China; Qing dynasty, reign of the Qianlong Emperor (1736–1795); hollow dry lacquer; 40 x 27 x 18 in. (101.6 x 68.6 x 45.7 cm); Asian Art Museum of San Francisco; The Avery Brundage Collection; B60S16+; photograph © Asian Art Museum of San Francisco

The exhibit is receiving rave reviews from many in the art world: “Faith and Empire is in my opinion the best show that the Rubin Museum of Art has put on in years so far as the quality of the material, the depth of the scholarship, and the appeal of the display,” said gallerist Walter Arader.

A scholarly and very beautiful catalog accompanying the exhibition is edited by Rubin Museum senior curator Karl Debreczeny. The Rubin Museum will also hold an international academic conference on Tibetan Buddhism and Political Power in the Courts of Asia on April 5-6, 2019, featuring Tsering Shakya as keynote speaker, with panels on Political Legitimacy and the Birth/Spread of Empires, Militant Lamas and Magical Warfare, and Systems of Power and Control of Knowledge.

The exhibition challenges present day popular perceptions in the West of Buddhism as an inherently apolitical and nonviolent religion, placing Tibetan Buddhist artworks into historical and political contexts spanning over a thousand years. The Buddhist artworks in the exhibition show how the conquest dynasties of Inner Asia melded an imperial program with religious authority to strengthen and perpetuate their rule.

The Tibetan state’s official adoption of Buddhism in 779 AD supplied it with a universal model blending sacral and temporal authority and a basis for the expanding political power in which political authority was inseparably intertwined with religion.

The Chakravartan, universal wheel-turning ruler was an Indian concept imported into Tibet under which the ruler was endowed with unquestionable authority and special powers in order to spread religion. Buddhist belief granted the ruler an esoteric means to physical power, using ritual magic to ensure success against his enemies. It also legitimized political succession through reincarnation. Shared Buddhist belief also provided a basis for transcending clan divisions, and uniting disparate political entities.

The exhibition takes the visitor through Tibetan and Chinese history, demonstrating how successive dynasties embraced Tibetan Buddhism as a means of fulfilling the role of the Chakravartan ruler, a sacrosanct rulership, exercising authority over the four continents.

Chogyel Phakpa (1235–1280); Tibet; 16th century; copper alloy with silver and copper inlays; height: 7 5/8 in. (19.5 cm); Yury Khokhlov Collection; photograph by Bashir Borlakov

Tibetan rule expanded far outside its mountain borders to become the chief rival to Tang dynasty China in the 7th century. Tibetans ruled over Chinese populations in the eastern area of the Silk Route. Tantric rites were an embodiment of its power, and magic became a tool of war as well.

When the Tibetan empire collapsed in the 9th century, Tibetan Buddhist practices and both Tibetan and Chinese artistic styles were incorporated by the succeeding Tangut court. In the Tangut kingdom, Buddhist rulers merged religious and political traditions under lavish imperial patronage. Tangut patrons utilized a deliberately multi-cultural strategy, mixing artistic styles and multiple languages to express the breadth and range of their ruling power.

The Mongol ruler Chengiz Khan was said to have been impressed by the magic powers of the Tangut preceptor in the field of battle against his forces, causing a dam to break by magic and overwhelm them. Mongol rulers brought Uighurs, Tanguts, and Tibetans to their courts, and after being installed as emperor, Kublai Khan was initiated into Tibetan Buddhist rites. Kublai Khan not only made his Tibetan preceptor the highest religious authority in Eastern Mongol state (it would become traditional for Mongol rulers to have a Tibetan preceptor) he eventually installed him as ruler and granted him suzerainty of Tibet.

Moving forward several centuries, in Tibet proper, the 5th Dalai Lama was identified as the incarnation of the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, cementing the theological underpinning for government authority, and linking present rule to past dynasties through the cycles of rebirth. The Potala palace in Lhasa also expressed a conscious linking of the sacred and temporal realms in architectural terms. (The building itself was reproduced in the Manchu summer capital in Chengde, Heibei Province.)

Ming rulers, especially the Yongle emperor (1403-1424) were also enthusiastic patrons of Tibetan Buddhism. The emperor Wuzhong styled himself as an emanation of the 7th Karmapa and taking the name of Rinchen Peldan.

Bodhisattva Manjushri as Tikshna-Manjushri; China; Ming dynasty (1368–1644), Yongle reign mark (1403–1424); gilt brass, lost-wax casting; 7 1/2 x 4 3/4 x 3 1/2 in. (19.1 x 12.1 x 8.9 cm); The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Rogers Fund, 2001; 2001.59

In the 17th -18th century, Chinese rulers claimed to be inheritors of the tradition of sacrosanct rule. The Qianlong emperor (1736-1795) is portrayed as Manjushri, and Tibetan inscriptions are included which identify him as Manjushri. Even the court painter Castiglione portrayed the Qianlong emperor as holding the golden wheel of the universal sacral ruler, and poised above him is his Tibetan court chaplain, Changkya Rolpe Dorje, reinforcing both the emperor’s divinely sanctioned rule and a priest/patron relationship harking back as far as Kublai Khan’s Mongol rule. There was even a belief that the Qianlong emperor himself was an incarnation of Kublai Khan.

The exhibition and catalog provide a rich and rewarding explanation of a thousand years of integration and enmeshing of artistic styles between Tibet, China, and Inner Asia, while political dynasties utilized a common religion as a basis for dynastic propaganda and even as a tool of conquest.

Sources: Courts, Politics, and Sino-Tibetan Artistic Exchange with Karl Debreczeny and Symposium: Art, Politics, and Tibet’s Eastern Neighbors

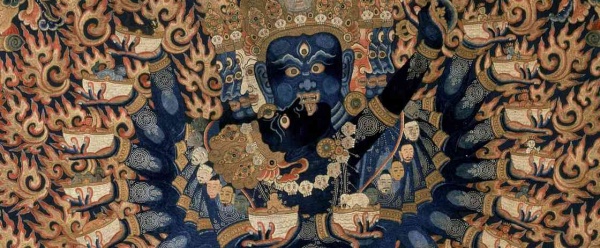

Detail of Hevajra; China; Ming dynasty, Yongle period (1403-1424), ca. 1417–1423; silk embroidery; 51 3/5 x 32 in. (131 x 81 cm); Pritzker Collection; photograph by Hughes Dubois, Detail permission courtesy Rubin Museum of Art.

Detail of Hevajra; China; Ming dynasty, Yongle period (1403-1424), ca. 1417–1423; silk embroidery; 51 3/5 x 32 in. (131 x 81 cm); Pritzker Collection; photograph by Hughes Dubois, Detail permission courtesy Rubin Museum of Art.