The following expansion of our September 5, 2023 article on Nepal is drawn from testimony to the Cultural Property Advisory Committee, Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, U.S. Department of State on the 2023 Request for a Memorandum of Understanding Between the United States of America and the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal.[1]

Please note that this website content is intended for informational purposes only. Nothing herein is intended to constitute legal advice.

PREFACE

We have addressed the Four Determinations below in the manner appropriate for the Cultural Property Advisory Committee, which is required by statute to make a judgment based upon whether a country’s request meets these criteria.

However, all the available evidence shows that an MOU ‘protecting’ the cultural heritage of Nepal under the CPIA is unnecessary.

This is not because Nepal’s government has done a good job protecting heritage.[2] In fact, the Nepalese government does not do a very good job of protecting and conserving the monuments it does control. While a few ancient monasteries and a number of shrines within Kathmandu have been beautifully restored since the 1990s (unfortunately, some of the most exceptional were severely damaged again in the 2015 earthquake) much of this work was undertaken early by independent foreign organizations such as the Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust, and since the quake by NGOs and grander international entities, not Nepal’s government.

Statute of Vishnu, Thakuri period, 1105, gilt copper, presented by His Majesty Mahendra Bir Bikram Shah to Chester Ronning, (c) Metropolitan Museum of Art.

An MOU is not needed because the time when Nepalese art and artifacts were being taken out of the country has long since passed. When Nepal opened to foreign visitors in the 1950s, it could be characterized as a country of weak domestic laws, barely enforced outside the Kathmandu Valley, in which ancient art and heritage was taken for granted, where shrines were poorly maintained and often completely neglected, and where responsibilities for monuments were delegated to their unpaid custodians. The government took a laisse faire attitude toward countryside monks who kept temples running by selling and replacing old gods with new ones, well-to-do rural landowners with an eye to the market were absentee or not closely tied to village communities, and officials, including from Nepal’s royal family, were eager to get a cut of a burgeoning tourist business that included an antiquities trade on the side.

Many objects now in US museums were knowingly waved through Nepalese Customs onto international flights by complacent officials who were given permission to do so by people at higher levels of government. Antiquities and antiques flowed like water over open borders out of Tibet and Nepal to India in the 60s and 70s. Ancient Nepalese and Tibetan objects were literally sold on the sidewalks of Janpath in New Delhi in the 1950s and early 1960s. One American visitor at the time, who became a major collector, expressed curiosity about the traditional paintings with cloth borders, thangkas, that he’d never seen before. The bemused owner of a Delhi antique shop led him to a large upstairs room where thangkas were piled four or five deep across the entire floor. There were hundreds and he bought the best thirty. The thangkas were long ago donated to American institutions.

The situation today is very different as a result of Internet repatriation campaigns, not responsible Nepalese government action.

The responsibility of the Nepalese government to protect ‘national heritage’ has been superseded by an intense publicity campaign led by Internet crusaders hostile to Western museums and the art trade. Their campaign is echoed by press journalists, mostly quite young, who have flooded the Internet with accusations that collecting art is an immoral, ‘colonial’ activity and that virtually all objects that left Nepal in the mid to late 20th century are stolen and must be returned. The stories are ubiquitous – it’s easy to find several a week having only to do with Nepal. Add in India and Southeast Asia and China (where the Xi government is strongly backing anti-Western cultural sentiment on social media[3]), and the number of “cultural claims” is uncountable.

Nepalese demands for repatriation began just a few years ago. The Lost Arts of Nepal (LAN)[4] and the Nepal Heritage Recovery Campaign (NHRC) originated with different groups of young activists, including many who came from the elite circles of Brahmin society in Nepal. The LAN uses crowdsourcing and computer image-matching to locate objects in online museum records, auction catalogs and advertising. Their primary references are the works of Ulrich von Schroeder and other scholars who collected and cataloged thousands of photographs taken by early travelers in Nepal. These black and white, often grainy images are ‘matched up’ with objects in museums and collections around the world.

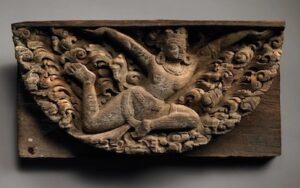

14th-century carving of a garland-bearing apsara, or spirit, that was originally part of an ornamental window in a Kathmandu monastery. Voluntarily returned to Nepal in 2022. Photo courtesy Rubin Museum.

On this basis, the bloggers allege that matching or similar objects were either stolen from temples or purchased legally from individual owners and exported without extant records of permission. As they see it, it does not really matter which. Because the premier antiquity hunters on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Tik Tok are anonymous, they can’t be held accountable when their claims far overstep the facts. Neither they nor the journalists that publicize these claims publicly hold Nepalese officials of their parents’ and grandparents’ generations responsible. The activists then push the otherwise somnolent Nepalese government to make claims for specific objects after the activists have located them.

It is certainly appropriate to identify and recover objects actually stolen from temples. No one questions the importance of doing so. U.S. museums have investigated these claims and in a number of instances, have returned objects to Nepal. However, the activists’ blanket approach has also resulted in claims for dozens of objects that left Nepal 40-50-60 years ago and for which there is no actual evidence of theft. Perhaps because the Nepalese government is sensitive about how government officials facilitated exports in the past, no evidence has been presented about when, where or how the objects left Nepal.

An MOU, which would only apply to objects that left Nepal less than ten years before its signing would have little or no use today because Nepalese art is no longer leaving the country for the United States. With weekly, sometimes daily articles appearing in the Nepalese press about ‘stolen artifacts’, no Nepalese official can look the other way while an object leaves the country. Although under Nepalese law, legal export is still possible today with authorization by Nepal’s government, no official or Customs officer in Nepal is likely to give permission for export, as has happened thousands of times before, for money or friendship. It would be political and professional suicide.

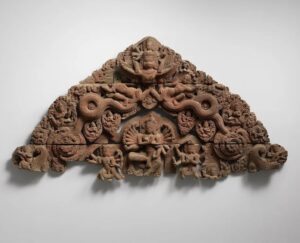

17th century torana taken from a temple complex in Nepal. Courtesy Rubin Museum of Art

Even more objects are being returned through U.S. museums’ own provenance research and thanks to additional publications of early photographs and drawings done decades before in Nepal. [5] Furthermore, with the constant threat of an anonymous claim of “looting’ or ‘theft’ punctuating the Internet, no U.S. museum would acquire an object or auction house sell an antique without first performing due diligence using Ulrich Von Schroeder’s books and other resources to ensure that the object was not stolen.

The greater weight given to Internet accusations over actual investigations makes clear the necessity and value of detailed documentation today. It also shows how imbalanced and weighty a burden is placed on museums and collectors of objects that left source countries decades ago, when source countries failed to follow the 1970s UNESCO recommendation that they establish permitting regimes and instead simply closed their eyes to the export of cultural property. Virtually every antiquity in America today legally entered the U.S – by law, all that U.S. Customs required was an accurate description and honest statement of age and value. No one wanted source country export documents and they were rarely kept. Because art source countries failed to follow their own rules, U.S. museums and legitimate dealers and collectors are at significant hazard today.

Introduction

The Cultural Property Advisory Committee is tasked by Congress to review applications under the 1983 Cultural Property Implementation Act (CPIA) for import restrictions on art and artifacts. In this case, the request comes from the Republic of Nepal. Our testimony below about the Four Determinations, shows how and why Nepal does not meet the criteria for an MOU under the CPIA today.

Manjushri #280 at National Museum of Nepal, Photo Anup Sadi, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

This request fails to meet the first and most essential criteria under the CPIA – that a country’s cultural heritage is in jeopardy – because Nepal’s cultural heritage is no longer threatened.

Neither collectors nor museums in the U.S., Europe, or other developed nations would consider purchasing an antique or ancient object from Nepal without a provenance far longer than one that would automatically exclude it from coverage under an MOU signed today.

There are large numbers of antique Nepalese objects in U.S. museums and private collections because in the more distant past, the Nepalese government ignored or was complicit in the export of objects by routinely allowing export. Government officials and even members of the royal family (such as a well-known ‘playboy Prince’) participated in the antiquities trade. For the last two decades, after such exports had ceased, Nepal’s government has ignored this history, because it caused embarrassment at the highest level. However, in the last few years, while the government remained largely silent, blogger organizations and the Nepalese press have very frequently reported that all antique items were not just illegally exported, but “stolen.”[6] They demand that foreign museums and collectors return objects that have been in global circulation for 30-70 years and have pushed Nepal’s government to follow through with official claims.

Nepal earthquake, 26 April 2015, photo by Nirmal Dulal, CCA-SA 4.0 International.

While the Nepalese government has been involved in heritage projects within Nepal, primarily the rebuilding and restoration of temples in the Kathmandu Valley, this involvement remains dependent of foreign organizations and foreign aid. Despite the terrible destruction in the massive 2015 Kathmandu earthquake, there is no indication of looting or removal of architectural heritage from damaged buildings as a result. The Western market wants nothing to do with such immoral activity.

Nepal’s request for import restrictions is misguided because import restrictions will not act to reclaim objects that left the country decades ago. The Cultural Property Implementation Act’s purpose is to remedy a serious situation of current looting that is bringing artifacts to the U.S. That is not the situation today.

What Criteria Must Be Met Under U.S. Law for an Agreement Under the Cultural Property Implementation Act (CPIA)[7]?

The request must satisfy all four requirements set forth in the statute. The requirements are:

- The cultural patrimony of the State Party (Nepal) is in jeopardy from the pillage of archaeological or ethnological materials of the State Party.

- The State Party has taken measures to protect its cultural patrimony.

- The application of the requested import restriction if applied in concert with similar restrictions implemented, or to be implemented within a reasonable period of time, by nations with a significant import trade in the designated objects, would be of substantial benefit in deterring a serious situation of pillage, and other remedies are not available.

- The application of the import restrictions is consistent with the general interest of the international community in the interchange of cultural property.

Nepal’s Request Fails to Meet Legal Criteria Under the CPIA

Determination #1: Is Nepalese cultural patrimony (its ancient and ethnographic art) currently threatened by pillage?

Manjushri with Shakti #264, National Museum of Nepal, CC license.

Nepal’s cultural patrimony is not currently threatened by pillage. Bronze and stone objects and architectural woodcarvings were frequently sold by custodians or stolen outright from temples and other sites in the 1970s and into the 1980s. An MOU will not address this earlier trade. U.S. import restrictions are intended to ameliorate current situations of looting, not to apply to objects that left a country 30-60 years in the past, when many Nepalese art objects were exported. The CPIA’s provision allowing import after an object is ten years out of the source country means that ordinary import restrictions would not apply. However, any object documented as stolen can be seized on entry without the need for import restrictions under the CPIA’s Section 308.[8]

Other US laws that are vigorously enforced today, notably the federal National Stolen Property Act, can and do make it illegal to knowingly possess, sell or otherwise transfer stolen goods, no matter how long ago they were stolen.[9]

Current Nepalese claims are not related to looting today.

No one can condone stealing votive sculptures or architectural elements. However, it is very clear from the extensive documentation now being undertaken by independent groups in Nepal – not the government, that thefts are now quite rare. There has been one widely publicized example of a theft from a temple in 2023. Two statues, one several hundred years old and one a replica on top of it were taken. Either of these items, regardless of age, would be deemed a stolen object in the U.S. and subject to immediate return, without an MOU. If these stolen statues are ever taken out of Nepal, the only places they will be welcomed are countries without US and Europe’s scruples about collecting such items. The Peoples Republic of China, where both Nepalese and Tibetan art is enthusiastically privately collected, would be their most likely destination.

U.S. museums and auction houses have recently returned a number of objects identified as formerly belonging to Nepalese temples by Internet activists.[10] U.S. museums are committed to reviewing their holdings to find others. However, some Nepalese activists continue to say that all Nepalese items in U.S. museums are “stolen,” despite lacking any evidence showing by whom, when or how they were illegally taken from Nepal.

Lakshmi-Narayana taken in 1984 from Nepal, returned by the Dallas Museum of Art. Photo courtesy Dallas Museum of Art.

Submissions to the CPAC urging signing of an MOU refer over and over again to “thefts” in 1972, 1982, and 1984, and other equally distant takings. Sculptures and other objects that have been identified as originally belonging to looted temples and shrines are being returned without question by U.S. and international museums. Thanks to research by the NHRC, a 12th century Laxmi-Naryan said to have been taken from Nepal 37 years ago was returned in 2021 by the Dallas Museum of Art. A gilded Mulchowk Torana stolen from Patan in the early 1980s was removed from an auction within 24 hours. No U.S. law or MOU was needed to force such returns.

However, during the same 40, 50 and 60 years ago period that objects like these were stolen by unscrupulous thieves, other free-standing sculptures and architectural elements were sold by the legal custodians of temples and replaced with newer idols, a typical practice in shrines. The majority of antique Nepalese votive figures that left Nepal in the 20th C were not taken from temples or village shrines, but legally sold by families. It is true that Nepalese law prohibited their export without authorization from government officials, but this was generally obtainable through shipping agents with government contacts.

Much of the art that has left via Nepal is Tibetan, not Nepalese.

Nepal also was a major transit point for Tibetan art that was rescued from Chinese seizure and destruction inside Tibet. Precise numbers are not available, but it is known that that much of the antique art that was exported from Nepal is not of Nepalese origin.[11] This art was rescued from Tibetan monasteries and temples by fleeing monks and other refugees and brought across the open border with Nepal to safety.

It is well established that Newari craftsmen from Nepal were some of the primary artisans working in Tibet for centuries. Further complicating the difficulty of identifying what is Nepalese and what is Tibetan is the fact that much of the finest art that has come from within the borders of today’s Nepal did not come from the Kathmandu Valley. Mid-20th C Nepalese considered the limits of “Nepal proper” to be the Kathmandu Valley and the Tibetan-speaking peoples who dominated regions outside the valley did not consider themselves “Nepalese.”[12]

If an MOU is signed with Nepal, China might have an equal or greater legal claim for Tibetan or Tibetan-like objects seized under an MOU. An MOU would favor China’s aggressive cultural claims and threaten Tibetan interests.

Determination #2: Has the Nepalese government taken steps to protect its cultural patrimony?

Nepalese laws allowed private ownership and export with official permission.

Nepalese laws on cultural heritage evolved in similar forms with other aspirational heritage legislation in the 1960s and 1970s in undeveloped countries around the world. Unlike many other heritage laws of the period, Nepalese laws did not vest ownership of antiques and antiquities in the State. Nepalese laws were not and still are not what are called ‘national ownership laws” today. However, like many other heritage laws in less developed countries, Nepalese laws were written without the administrative or enforcement support to implement them.

Visitation of the Bhairavnath temple of Bhaktapur Katmandu Valley, Nepal 1970s, photo by United Archives / Walter Rudolph, CCA-SA 3.0 Unported.

Historically, the focus of Nepal law has been on monuments and objects of reverence of Hindu or Buddhist origin. Private ownership of both antiquities and monuments was permitted although the government could purchase objects or sites at risk for a ‘reasonable price’. Objects for private worship were also not required to be registered, although it does not appear that objects in temples and monasteries were documented either. The types of objects restricted from export under 1956, 1968, 1969 and 1970 laws were in many cases unclear, and the government continued to have discretion to allow export throughout the 20th and early 21st century.

Neither the UNESCO Database of National Cultural Heritage Laws[13] nor the International Foundation for Art Research ICPOEL database[14] has an original copy of Nepal’s 1956 Ancient Monument Preservation Act. IFAR has only amended versions for 1994 and 2013, which have footnotes generally indicating changes made through the various amendments.

A single page from the Nepal Gazette of April 7, 1969 contains the earliest unamended document available on the UNESCO website.[15] It describes the types of historical, archaeological and artistic objects which are “prohibited the export thereof from the Kingdom of Nepal or their movement from one part of the Kingdom of Nepal to another without the prior permission of His Majesty’s Government” (my emphasis):

“1. Historical Objects

Hand-written Vamshawalis giving historical accounts of any country; Manuscripts, gold-plate inscriptions, stone inscriptions, copper-inscriptions, wood inscriptions, birch-leaf-inscriptions, palm-leaf inscriptions, documents, coins, houses where historical events had occurred or which were occupied by historical personalities, and objects used by such personalities.

- Archeological objects

Objects made or used by human beings of the pre-historical period.

- Artistic Objects

Any important part of the house constructed in an impressive manner with figures carved on wood, stone, clay, bone, cloth, paper, metal, etc; objects used in such houses, images, temples of god and goddesses, pagodas, statues, inns, etc built with or without such reproductions of animals and birds or of both animate and inanimate objects.”

The 1996 Fifth Amendment to the law[16] attempted to require regular maintenance and conservation of temples and shrines. However, the Department of Archaeology was only tasked with conserving major monuments:

“(1) The Conservation, maintenance and renovation of the ancient monuments under private ownership which are inside the Protected Monuments area shall be carried out by the concerned person. Provided that if it is deemed necessary to conserve, maintain and renovate the private ancient monuments which are of importance from the national and international view point, by the Department of Archaeology, the Department of Archaeology may, conserve, maintain and renovate such ancient monuments.”

At the same time, the government pushed responsibility for maintenance on to religious organizations:

“3E. Operation of Religious Temples, Monasteries, etc. (1) The person operating a religious temple, monastery etc. shall use up to fifty percent of the amount of the donation offered to such temple or monastery for the conservation of the temple or monastery and for bringing reformation in its surrounding environment.”

Santaneshwar Mahadev located at Indra Chowk, Kathmandu. Devotees who do not have children come here to worship and hope for children. Photo Rajesh Dhungana, 18 July 2021, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

Nepal’s 2010 amendment of the 1956 Ancient Monuments Preservation Act, 2013 [2013 Nepal year is the original year enacted, equal to 1956 CE], lists eight amendments to which it has been subject, ending in the Republic Strengthening and some Nepal Laws Amending Act of 2066 [Nepal year] (2010 CE). This last Act includes significant updates to the types of Ancient Monument to include houses, temples and institutional buildings of importance and more than 100 years old (only added by the 1986 Amendment). An “Archaeological Object” can include a very wide variety of objects that are either “pre-historic” or “any immovable or moveable objects which depict the history of any country.” The 2010 Act requires government permission for various types of development including the use of explosives at a protected monument.

The 2010 Act continues to place responsibility for maintenance and care of “private ancient monuments” on the private owners, who must allocate half of the monument’s revenue for upkeep and repair. It states briefly that Private Ancient Monuments may be purchased by the State if the Government deems it necessary for an “evaluated price,” but has many more pages on the various responsibilities of private owners.

Article 13 of the 2010 Act is consistent with the 1964 Amendment[17] that prohibits any historical, archaeological, or artistic object from being transferred to other places around Nepal or exported from Nepal without prior approval of the Government of Nepal.

One can assume, based upon Nepalese law in 1996 and even 2010 that during prior decades when most Nepalese artifacts were taken from the country, export without government permission was unlawful, but Nepal did not claim government or national ownership of antiquities. Religious sculptures, certain shrines and other religious edifices, ancient monuments on private lands, and family gods and religious paraphernalia such as thangkas, manuscripts, and paintings continue to be lawfully held in Nepal under private ownership today.

Temple of Bhringareshwar Mahadev, Photo Rajesh Dhungana, 27 August 2021. Photo Rajesh Dhungana, 11 October 2021, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

The 1970 law,[18] which was in force during the latter part of the period when most objects left Nepal, states that the identification of what constitutes an archeological object prohibited from export is in His Majesty the King’s discretion. (my emphasis) There was an open commercial trade and frequent export of various ethnographic materials, books, metalwork, costumes, woodcarvings, antique rugs and textiles from Nepal in the 1970s and 1980s without restriction. In practice, Nepalese export laws do not appear to have pertained to objects other than religious materials at this time or to have been strictly enforced.

Under Nepalese law, objects requiring government permission for export included antiquities that were imported into Nepal without official registration. Notably, this could be interpreted as a claim to Tibetan objects brought into Nepal by fleeing refugees, which like all imported antiquities, are supposed to be registered on entry, but never were. Nepalese laws also allowed for re-export of registered foreign cultural property, but as registration was practically unknown, this would make Tibetan objects un-exportable by default .

In the 20th C, Nepalese rulers encouraged export for exhibition and study of Nepalese art.

His Majesty King Mahendra Bir Bikram Shah of Nepal (1920-1972) at his coronation in 1955

Regardless of the statements on paper under Nepalese law, Nepal was not only lax in enforcement of its cultural heritage laws, the Nepalese government often gave official blessing to export of very important artworks. Some of the earliest major exports were made for the express purpose of having exhibitions in Western museums in order to show the beauty of Nepalese art and celebrate the skill of its artisans. The return of these works has never been expected or sought by the government of Nepal.

As a landlocked country that was all too aware of the need to get along with its far more powerful neighbors, India and China, Nepal’s royal family was eager to promote Nepalese culture and celebrate Nepalese identity. In the 1950s and 1960s, there were no barriers placed to the export of objects collected by the scholar Stella Kramrisch for the Philadelphia Museum of Art or to other exports of objects for study and museum collections. Nehru himself facilitated Kramrisch’s exports from India.[19]

Scholars and the art dealers who came soon after were probably aware that there were laws on paper forbidding export, but also knew that with the active support of the Nepalese elite, export continued to be allowed. Given the direct involvement of royal Princes of the Rana dynasty in the art trade, the availability of objects for sale, and the fact that air shipping agents routinely acquired permission for export, the ways and means of export were common knowledge.

In a recent article, Gautam Vajra Vajracharya states that the promotion of Nepalese art through international exhibitions in the 20th century led to a rapid expansion in international collecting:

“During the reign of King Mahendra and a few decades before that, Nepali artefacts… had started to be respectfully displayed in various international museums. From an immediate point of view, this was a matter of pride for Nepal… King Mahendra’s intention was to make Nepal famous not only as an independent country but also as a beautiful country in the lap of the Himalayas full of its own art. So King Mahendra was overjoyed when Stella Kramrish, a senior curator at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, proposed organizing the first international exhibition of Nepali art [in 1964]. It was not difficult to get permission to take Nepali artefacts out of the country for some time for the exhibition to be held outside the country.”[20]

Cultural property laws were one element in King Mahendra’s mid-20th C deliberate project of nationalism.

Ethnographic map of Nepal. Dr. Harka Bahadur Gurung (1939–2006), 24 December 1998, CCA-SA 4.0.

Nepal was recognized as a national entity by its neighbors, but before the mid-20th C., within Nepal itself, there was not a concept of “Nepal-ness” among its citizens outside of Kathmandu. King Mahendra selected a “national language” from among a huge variety of tongues, deliberately displacing Hindi as a lingua franca, made use of Nepali rather than Indian currency compulsory, introduced a constitution, a national flag and a national anthem, set development policies, regulated hitherto unregulated industries, and brought electrification to the countryside. Nepal became a member of the United Nations in 1969 and King Mahendra traveled outside the country to make diplomatic connections.

It was during the same period, the mid-1950s to mid-60s, that the first laws on cultural heritage were promulgated. These laws should be seen within this context, as another facet of Mahendra’s attempts to define a Nepalese identity within the diversity of cultures that was Nepal and as part of his campaign to show the world that Nepal could act as other nations did on the world stage.

Nepal’s population around Kathmandu is largely Hindu, while many rural regions are predominantly Buddhist, speaking Tibetan or Tibetan-related dialects.

Ashoka Pillar at Gotihawa in Kapilvastu District. Photo Rajesh Dhungana, 11 October 2021, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

Hindu, rather than Buddhist art, is more closely tied to Nepalese “identity.” Nepal is home to powerful competing forces within its strong caste system: the descendants of Buddhist merchants and priests, urban Sresthas, village patrons, Brahman kingly councilors, and various lower castes.[21] For all the claims by activists of “national identity” being harmed by the removal of Buddhist art and artifacts, in Nepal’s 2011 census, the most recent completed, Hindus constituted 81.3 percent of the population, Buddhists 9 percent, Muslims (the vast majority of whom are Sunni) 4.4 percent, and Christians (of whom a large majority are Protestant and a minority Roman Catholic) 1.4 percent. Buddhists are very much a minority, there being only twice as many Buddhists as Muslims.[22] Tibetan refugees, who are Buddhists, are not registered, so while the number of people with a “Buddhist identity” is somewhat higher, they are neither Nepalese citizens nor do they have access to even the limited social services and opportunities available to Nepalese.

Nepal’s impoverished rural communities could not maintain temples or resist Nepalese feudal lords who sold objects from the countryside.

Vajracharya also notes that the various parties’ role in land reform and the impoverishment of Newar communities was a factor limiting public religious activities and that the unfunding of temples enabled idols to “disappear unnoticed.”[23] Traditionally, local shrines and temples had been supported by the communities surrounding them. The communities’ ability to maintain them had been decreasing for decades as a result of village and rural impoverishment under Nepal’s oppressive feudal structure. The 1996-2006 civil war with Maoist insurgents in the countryside did nothing to remedy the hardship and privations of country people’s lives and further discouraged the maintenance of disused or abandoned shrines.[24]

Western observers, not the Nepalese government, raised the first objections to removal of objects. These observers blamed Nepalese officials for not enforcing laws and allowing export.

The inner part of the Bhadrakali Devi of Kathmandu. Photo Rajesh Dhungana, 09 July 2021, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

In 1998, Jürgen Schick’s The Gods Are Leaving The Country; Art Theft from Nepal, first made public how idols were taken from shrines and monuments in the Kathmandu Valley in the second half of the 20th century. Schick’s book made clear that the Nepalese government had not only failed to protect historical monuments of great importance, even within the capital of Kathmandu, but that Nepalese officials either ignored or were complicit in the removal of sacred statues.

As Schick stated in 1998 in The Gods Are Leaving the Country:

“There is, to be sure, a law stating that no work of art more than one hundred years old may be taken out of the country. That’s what is written on paper; the reality of the situation makes a mockery of the law.

Nepalese have been waiting in vain for effective countermeasures by the state, even though it is normally the duty of the government to protect the nation’s art treasures. Thus it is up to the affected persons themselves, the faithful, the priests, the temple watchmen, to provide assistance on their own, to the extent they can.” [25]

Schick blamed the removal of the gods primarily on the influx of foreign aid into the country and the kindling of desire for consumer goods like motorcycles, radios and household luxuries among the Nepalese. He blamed a growing number of problems in Nepal on materiality and argued naively for a return to a much less sophisticated “natural,” even primitive way of life.

The Itumbaha Museum. Goodwill or ‘neo-colonialism’?

Itumbaha Museum, Nepal, Photo courtesy Rubin Museum NYC.

An important example of how the CPAC should be wary of accepting statements by Nepalese activists about rampant theft by U.S. museums and collectors may be seen in the response to a Nepalese community’s request for help from a U.S. museum. A recent gift of funding and offer of technical expertise from the Rubin Museum in New York that enabled a community group to open a local museum planned since the 1990s has met with solid support from some Nepalis and fierce criticism by others.[26]

In the early 1990s, local residents discovered over 500 ancient items in very bad condition in a storeroom in an important 11th-century monastery complex in the Kathmandu Valley. They established an organization, the Shree Bhaskardev Sanskarita Keshchandra Krit Paravat Mahavihar Conservation Society, to preserve the objects and developed a plan for an Itumbaha Museum to exhibit them, but eventually abandoned the plan because the government declined to fund it.

Itumbaha Museum, Nepal, Photo courtesy Rubin Museum NYC.

After the 2015 earthquake, foreign organizations became involved in restoring the building complex and the museum plan was revived. Each ancient item was removed from storage and cleaned. Still unable to obtain Nepalese government assistance, the locals contacted the Rubin Museum in N.Y. and asked for help. The Rubin provided $20,000 in funding as well as technical expertise. A new Itumbaha Museum was completed and opened in July 2023. Throughout, the project was designed and developed by Nepalese, with the support of foreign organizations.

However, since the opening of the Itumbaha Museum this July, at least a dozen articles in the Nepal press have focused on objections to the project, alleging that the Rubin’s gift was a continuation of the museum’s abuse of Nepalese heritage and a conspiracy intended to replace the community’s traditional ownership with a Western-imposed perception of culture. Unjustified claims of theft by the Rubin Museum proliferated. One article critical of the Rubin Museum featured an illustration that was simply a page from the online catalog of the Rubin Museum, where the museum identified objects as either from “Nepal” or “Tibet or Nepal.” The news article labeled it, “List of idols stolen from Nepal.”[27]

Some applauded the Rubin’s offer of financial and technical assistance to the community. A Nepalese cultural specialist, Swasti Rajbhandari from Lumbini Buddhist University, said that “Rubin helped the Itumbhal residents in their long-standing dream of opening a museum in their vihara… Many viharas have such wealth lying around, there is no record. Becoming a museum in this way is positive.”[28]

However, other extreme opinions dominated press coverage in Nepal. “Instead of apologizing for hurting cultural and spiritual sentiments, Rubin has taken the lead in showing a new form of colonialism,” said the Chairman of Museum of Stolen Art, Ravindra Puri.[29]

Determination #3: U.S. import restrictions may be implemented only if applied in concert with similar restrictions implemented, or to be implemented within a reasonable period of time, by nations with a significant import trade in the designated objects, would be of substantial benefit in deterring a serious situation of pillage, or establish that other, less drastic remedies are not available.

There is no evidence that a U.S. market for Nepalese antiquities and ethnographic materials has triggered a current “serious situation of pillage.” Therefore, an MOU cannot be “of substantial benefit” in stopping something that is not occurring. There are currently more than adequate numbers of objects on the art market in the U.S. and Europe from collections made in the mid to late 20th century now being dispersed due to the death or old age of the collectors. Import restrictions will only impede the circulation of art that has been outside of Nepal for 30-60 years, but which no longer has records of legal export.

Determination #4: Is the application of the import restrictions consistent with the general interest of the international community in the interchange of cultural property?

Artistic and Cultural Borders are Not the Same as Political Borders

Outside the Samai Mai temple, an idol of an elephant is offered when the wishes of the devotees are fulfilled. Photo Rajesh Dhungana, 22 November 2021, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

Enforcement of a blockade on “Nepalese art and artifacts” based upon today’s recognized international boundaries also makes little sense because of the difficulty in distinguishing between Tibet-made and Nepal-made objects and the inconsistency of today’s boundaries with those at the times that objects were originally exported.

For example, as Nepal was not widely opened to tourists until the 1960s, India was the first marketing destination for Tibetan art in the1950s. According to art historian Dr. Pratapaditya Pal,[30] who traveled to Nepal in 1957 to document Nepalese art and architecture, there was no passport required and no Customs between India and Nepal at that time, and even later, in the 1960s. Dr. Pal recalls clearly how in 1952 or 1953, when he was an undergraduate in Delhi at St. Stephens College, he was shocked to see that the footpaths of a main shopping street, Janpath, in front of two hotels, were taken over by Tibetan refugees selling art. He recalls purchasing several sculptures, including a very old Indian Ganesh, but brought from Tibet by Tibetans, which he gave to his mother.[31]

Treasures brought by Tibetans to Nepal included “foreign” antique Indian textiles from the 12th-15th century that had been brought to Tibetan monasteries centuries ago by pilgrims. Would such objects be deemed restricted under an MOU with Nepal? [32]

Scholarly Knowledge and Research in the West

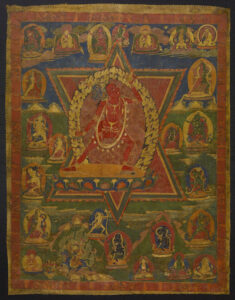

Anonymous (Nepalese). ‘Mandala of the Sun God,’ 16th century. watercolors on cotton. Walters Art Museum.

While Nepal is today producing dedicated students of Nepalese heritage, scholarship inside Nepal itself cannot yet be compared with the art historical scholarship, technical understanding and the deep knowledge of Buddhist practice that six decades of solid study has built in the West. This is not “western” scholarship, since many of the greatest Nepalese and Indian (and also Japanese and Chinese) scholars of Buddhist and Hindu art have emigrated to Europe and America and work together within a truly international academic milieu. There is simply an enormous body of scholarly work extant in the West that has benefited by decades of truly international scholarship and expertise.

European and American universities and museums support an international scholarly community that welcomes emerging scholars from across the globe. U.S. museums in particular have built major collections of Tibetan and Nepalese art within the Tibetan tradition with the support of knowledgeable collectors who want more than anything to donate their collections for the public benefit.

The expansion of scholarly knowledge regarding Nepalese art could not have taken place on this scale without a number of very successful U.S. museum exhibitions featuring Nepalese and Tibetan art, global awareness of the shocking destruction of heritage by China in Tibet and the popular enthusiasm for Tibetan Buddhist thinking and widespread, global adoption of Tibetan Buddhist practice in the second half of the 20th century.

Politics in Nepal: The Nepal – Tibet – China Problem

Policy regarding Nepalese art and heritage inevitably involves the future of Tibetan heritage as well. Unlike any other art-source country in the world, a high proportion of antiquities exported from Nepal in the past are not of Nepalese origin. They are from another country, Tibet. Tibet was invaded by China in the years 1950-59, its sovereignty usurped, and its ruler, the Dalai Lama, was driven into exile with thousands of his followers. In this period and in the Cultural Revolution that followed, China destroyed 95%-98% of the monasteries and shrines in Tibet.

Tibetan (Artist)

18th century

tempera and gold on cloth, Walters Art Museum. CC license.

It is a fact that it requires a specialist art historian to identify the difference between Nepalese and Tibetan artworks – that is, between (1) votive images and other artworks made in Tibet by Tibetans, (2) artworks made in Tibet by Newari (Nepalese) artisans as commissions for Tibetan monasteries, (3) artworks made by Newari (Nepalese) artisans in Nepal and (4) artworks that were made for communities in Greater Nepal that are actually Tibetan in language, culture, and religious practice. Even scholarly, well-respected art historians can differ on the actual origin of an object – and its life and travels over a period of centuries.

The majority of ancient Buddhist sculptures, thangkas, religious implements, textiles, manuscripts and books that were shipped out of Nepal in the second half of the 20th century were actually objects brought by Tibetans fleeing from China’s destruction of religious institutions and the subsequent violent oppression of the Tibetan people and their Buddhist religion. Religious leaders, humble monks from lamaseries and other religious organizations and refugees carrying personal possessions fled to Nepal and to northern India, bringing whatever precious religious texts and ceremonial objects they could carry with them. Western interest in the art of the region was greatly spurred by the arrival of these thousands of examples of Himalayan art.

The Dalai Lama on Western Museums and Tibetan Art

The 14th Dalai Lama has reminded the world many times of the key role that objects from Tibet and Nepal have played as messengers around the globe for Buddhist and Hindu thought. His Holiness has also spoken many times about the importance of collectors and museums safeguarding Himalayan art and artifacts so that Tibetan culture can be preserved for future generations. The Dalai Lama has actively supported the collecting of Tibetan art by Western and other foreign collectors and its display in global museums.[33]

View of Tibetan shrine room from the Alice S. Kandell Collection at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Asian Art, screenshot from 3D image by John Bigelow Taylor (2017).

Objects from Tibet, despite some being made by Newari Nepalese craftsmen, have very different roles than as ‘national heritage.’ The outside world has an obligation to steward the relics of a Tibetan culture that was deliberately destroyed by Communist Chinese forces.

Exhibitions of Tibetan art have had enormous public educational benefit. They have been instrumental in making the public aware of the scope and range of Asian art and cultural expression. With the active encouragement of Tibetans in the diaspora, Tibetan art has become a vehicle for spreading Tibetan cultural and religious ideals. With the Dalai Lama acting as a spiritual ambassador at large, the Western world has been exposed and opened to ideas previously little known – the Buddhist values of contemplation, meditation, and compassion.

As well as being distinct historical objects of art and connoisseurship, Nepalese and Tibetan artworks are displayed in several museums in ‘shrine rooms’ intended as religious spaces that will encourage visitors to appreciate the spiritual values they embody. In 2011, when Dr. Alice Kandell gave the National Museum of Asian Art at the Smithsonian several hundred objects forming a complete Tibetan shrine[34] (an exhibit that became the most popular in the museum’s history), the Dalai Lama attended the announcement of the gift.

The Dalai Lama told Kandell:

“Your intention is very good. Showing Tibetan art and providing an explanation is important. People will gain a deeper understanding of the Buddha and a way of thinking that is very much based on peace and compassion.” [35]

Enactment of an MOU with Nepal could have catastrophic consequences for the preservation of Tibetan heritage outside Tibet. Due to the similarities between Tibetan and Nepalese artworks, there is significant risk that Tibetan objects would be caught up in import restrictions on Nepalese art, harming Tibetan efforts to preserve Tibetan heritage in the diaspora. This would only add to the United States’ and the rest of the free world’s serious concerns about China’s ongoing, brutal destruction of Tibetan culture, religion, language, and heritage within Tibet.

Tibetan Human Rights in Nepal

The Nepalese government has discouraged rather than encouraged the preservation of Tibetan culture in Nepal. It has recently made life considerably more difficult for its long-resident Tibetan refugees in an apparent bid to strengthen its relations with China, with which Nepal shares a lengthy and sometimes contested border. The Nepalese government’s ongoing relations with China have specifically included cooperation with China’s Belt and Road Initiative.[36]

In 2021, the Nepalese government once again failed to accept recommendations regarding its treatment of Tibetan refugees during its United Nations Universal Periodic Review (UPR). Speaking of the UPR report on Nepal, Secretary-General Adilur Rahman Khan, Secretary General of the International Federation for Human Rights, made clear that while Nepal should be praised for hosting Tibetan refugees for decades, its government should take urgent steps to grant them legal status and ensure that their fundamental human rights are protected.[37]

The United Nations UPR drew attention to Nepal’s failure to accept a recommendation that it register and verify Tibetan refugees, and follow up by providing them with identity documents, which they are currently denied. The report described,

“the challenges Tibetan refugees face in Nepal, including lack of access to education, legal work opportunities, or medical and other government services. This lack of legal status leaves them vulnerable to crime and human rights violations with no recourse before the law.”

Nepal also would not accept the recommendation that it commit to the respect the principle of non-refoulement – that is – not to send refugees back to countries where they would face persecution or danger.[38]

Dalai Lama speaks to a large crowd on the National Mall during the 2000 Smithsonian Folklife Festival which featured a program on Tibetan Culture Beyond the Land of Snows. Photo by Jeff Tinsley, 2000, Wikimedia Commons.

Nepalese government interference extends to ordinary celebrations among the refugee Tibetan Buddhist community. According to the International Campaign for Tibet, events such as the July 6 celebration of the Dalai Lama’s birthday, an event marked with traditional worship by the Tibetan community at the Boudha stupa in Kathmandu, have periodically been forbidden, with dozens of police in full riot gear blocking the entrance to worshippers.[39] Political events such as the international Tibetan Uprising Day and Tibetan Democracy Day are completely forbidden.

The U.S. State Department’s Nepal 2022 Human Rights Report concurs, stating that the Nepalese government routinely denies freedom of expression among Tibetan refugees and restricts their freedom of assembly and freedom to travel. Nepal has not issued personal identification documents to Tibetan refugees for 25 years, subjecting them to police harassment and halting their ability to travel both inside Nepal and internationally. Since 1995, even refugee children born in Nepal have not been given identification documents or allowed to attend school in Nepal. Tibetan refugees are officially denied permission to work, although most manage to find at least poorly paid labor. The Nepalese government allows NGOs to provide separate schooling and other basic services but does not permit Tibetans to attend higher education, even in private institutions – or to obtain professional licensing in medicine, nursing or engineering. They cannot have driver’s licenses, bank accounts, or own property.[40]

When Tibetan refugees risk their lives to escape China, they hope to make their way to India where they can receive documents and hope to work there or to travel further to the West, where they can be received as refugees. Nepal has ignored its informal agreement with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees to allow Tibetans to travel through Nepal enroute to India. Instead, Tibetan refugees are being arrested far inside Nepal, robbed by police and returned “to Tibet at gunpoint, where they are typically imprisoned and not uncommonly tortured by the Chinese.”[41]

“According to a confidential U.S. embassy cable published by WikiLeaks in 2010, China “rewards [Nepalese forces] by providing financial incentives to officers who hand over Tibetans attempting to exit China.” Another cable stated, “Beijing has asked Kathmandu to step up patrols … and make it more difficult for Tibetans to enter Nepal.”

“In 2009, Beijing promised to promote tourism to Nepal, invest in major Nepalese hydropower projects, and increase its financial assistance by approximately eighteen million dollars annually. In return, Kathmandu pledged to endorse Beijing’s “one-China policy” (which decrees that both Taiwan and Tibet are “inalienable parts of Chinese territory”) and to prohibit “anti-Chinese activities” within Nepal.”[42]

The situation is said to be worsening today as Nepal actively pursues strengthening its economic relations with China. Concerns over Nepal’s abusive denial of basic human rights to Tibetans raise an important argument against an MOU with Nepal, based on the already precarious situation of Tibetan culture and the threat posed by Nepal’s closer relations with China today. Nepalese politicians and public officials have recently parroted specific policies set forth by Chinese officials characterizing Tibetan refugees as “infiltrators” and potential terrorists.[43]

In effect, an MOU with Nepal could easily result in the seizure of Tibetan artworks, made in Tibet by Tibetan or Newari craftsmen. Claims to these artworks by China, which also has an MOU with the U.S., would be devastating for the Tibetan community in exile. China is currently going further than ever before to crush Tibetan, language, Tibetan religion, and Tibetan identity inside Tibet. Through its forced sterilization programs and its mandatory taking of 900,000 Tibetan children from their families and placing them in locked boarding schools, China is committing genocide in Tibet. Tibetan artistic culture in Tibet has been another victim of Chinese repression and its campaigns touting Han superiority.

Under all these circumstances, the application of import restrictions cannot be consistent with the Fourth Determination required for an MOU, that it would “serve the general interest of the international community in the interchange of cultural property.” An MOU with Nepal should be denied on the basis that it does not meet the statutory requirements set by Congress and enshrined in U.S. law.

Cultural Property News wishes to thank Dr. Pratapaditya Pal, the world-renowned authority on Indian and Nepalese art, for sharing his many insights into early scholarly research and collecting in Nepal. Stay tuned to CPN for a wide-ranging interview with Dr. Pal, the author of some 90 works on Asian art, and one of the first to bring exhibitions and museum collections of South Asian art to American museums, coming soon.

NOTES

The content of this website is for informational purposes only. Nothing herein is intended to constitute legal advice.

[1] The original testimony was submitted by the Committee for Cultural Policy, Inc. POB 4881, Santa Fe, NM 87502. www.culturalpropertynews.org, [email protected], 505-216-9369. Global Heritage Alliance, Inc., 5335 Wisconsin Ave., NW Ste 440, Washington, DC 20015, [email protected], (202) 331.4209.

[2] Nor is it because Nepal is short of temples full of idols. Most Nepalese households, Hindu or Buddhist, still maintains a shrine for daily worship and many family shrines hold gods that are also valuable antiques. Nepalese law does not interfere with objects for private worship and limits full government control to ‘public monuments,” generally the most ancient and imposing in the Kathmandu Valley.

[3] For example, the Chinese government appears to have backed a high production value series of videos called Escape from the British Museum, in which a very attractive Chinese “influencer” in ancient dress explains that she is actually a Jade Teapot that has been weeping inconsolably because she is trapped in the British museum and wants to go home. The series has racked up almost 300 million views on Tik Tok.

[4] These campaigns began as Nepalese versions of the hunt-for-the-missing-idol efforts of expatriate Indian blogger Vijay Kumar’s India Pride Project but have outdistanced his early efforts. See: https://theprint.in/theprint-profile/vijay-kumar-the-art-blogger-enthusiast-who-helped-modi-bring-back-157-artefacts-from-us/741055/

[5] For example, in August 2022 the Metropolitan Museum of Art in NY returned a 13th century wooden Temple Strut with a Salabhinka that it was given in 1991 to the Government of Nepal, after the museum’s research determined that it came from the Itumbaha monastery in Kathmandu. Earlier, a tenth century stone sculpture, Shiva in Himalayan Abode with Ascetics, a gift to the museum in 1995, was transferred to Nepal in September 2021after the museum determined that it belonged to the Kankeswari Temple (Kanga-Ajima) in Kathmandu, Nepal. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Returns Sculpture to Nepal, August 15, 2022, https://www.metmuseum.org/press/news/2022/return-of-sculpture-to-nepal

[6] See, for example, “Another museum inside Itumbahal Vihar with the help of a foreign museum that has accumulated heritage stolen from Nepal! It has become an easier way to steal: Heritage expert Sudarshan Tiwari,” Ekatipur, July 22, 2023, objecting to the gift of $20,000 in funding from the Rubin Museum to a Nepalese community group as a new form of colonialism. ekantipur.com/news/2023/07/26/169037594004595679.html.

[7] Convention on Cultural Property Implementation Act, 19 U.S.C. §§2601-2613.

[8] Stolen Cultural Property: 19 U.S.C. § 2607, “No article of cultural property documented as appertaining to the inventory of a museum or religious or secular public monument or similar institution in any State Party which is stolen from such institution after the effective date of this chapter, or after the date of entry into force of the Convention for the State Party, whichever date is later, may be imported into the United States.”

[9] The National Stolen Property Act of 1934 (NSPA) (18 U.S.C. §§ 2314 et seq.) prohibits the transportation in interstate or foreign commerce of any goods with a value of $5,000 or more with the knowledge that they were illegally obtained and prohibits the “fencing” of such goods.

[10] https://nepalheritagerecoverycampaign.org/laxmi-narayana/ and https://nepalheritagerecoverycampaign.org/mulchowk-torana/

[11] Personal communication, Interviews with Dr. Pratapaditya Pal, May 2023, Los Angeles. Dr. Pal, the author of more than 90 books on South Asian and Nepalese art, has worked in Nepal since 1957.

[12] Id.

[13] UNESCO Database of National Cultural Heritage Laws, https://en.unesco.org/cultnatlaws.

[14] IFAR International Cultural Property/Ownership & Export Legislation, https://www.ifar.org/icpoel.php?region=asia.

[15] Nepal Gazette, Vol. 18, No. 51, Chaitra 25, 2025 (April 7, 1969) Issued by the Ministry of Education and signed by Dirgha Haj Koirala, Acting Secretary to HMG.

[16] Ancient Monuments Preservation (Fifth Amendment) Act, 2052 (1966), 8 March 1996.

[17] Ancient Monuments Preservation (First Amendment) Act, 2020, 1964.

[18] Ancient Monuments Preservation (Second Amendment) Act, 2027 (1970).

[19] Personal communication, Interviews with Dr. Pratapaditya Pal, May 2023, Los Angeles. Dr. Pal worked very closely with Stella Kramrisch during his first journeys around Nepal in the 1950s and later throughout her academic career.

[20] Gautam Vajra Vajracharya, How Did Nepali Idols Get From Temple to Museum, Himalkhabar, 16 August 2023 (2078), https://www.himalkhabar.com/news/125661

[21] Contested Hierarchies: A Collaborative Ethnography Of Caste in the Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. Edited by David Gellner and Declan Quigley. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995

[22] 2022 Report on International Religious Freedom: Nepal, Office of International Religious Freedom

[23] Supra fn 20.

[24] “The Nepalese Civil War was a protracted armed conflict that took place in the former Kingdom of Nepal from 1996 to 2006,” Nepalese Civil War, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nepalese_Civil_War

[25] Jürgen Schick, The Gods Are Leaving the Country; Art Theft from Nepal,1998, Orchid Press Publishing, p 39.

[26] Another museum inside Itumbahal Vihar with the help of a foreign museum that has accumulated heritage stolen from Nepal! It has become an easier way to steal: Heritage expert Sudarshan Tiwari, Ekantipur, July 22, 2023, objecting to the gift of $20,000 in funding from the Rubin Museum to a Nepalese community group as a new form of colonialism. ekantipur.com/news/2023/07/26/169037594004595679.html.

[27] Id.

[28] Id.

[29] Nasana Bairacharya, Itumbaha Museum: A new era of reviving heritage or a cautionary tale for the impending chaos?OnlineKhabar, August 13, 2023.

[30] Personal communication, Interviews with Dr. Pratapaditya Pal, May 2023, Los Angeles.

[31] Id.

[32] Similar textiles, which had been imported into the U.S. in the 1970s, then exported to the U.K., were offered to an American museum in the 2010s, which declined them on the grounds that their legal provenance (Indian, Nepalese, or Chinese) could not be determined.

[33] The author had the privilege of meeting the Dalai Lama in Los Angeles in the 1980s, where he attended an exhibition of Tibetan art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art hosted by its Collecting Council for Indian, Islamic and Ancient Art, and spoke with approval of Western museums safeguarding and sharing Tibetan heritage.

[34] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Receives Leading Collection of Tibetan Buddhist Art from Alice S. Kandell, Smithsonian, July 20, 2011, https://www.si.edu/newsdesk/releases/arthur-m-sackler-gallery-receives-leading-collection-tibetan-buddhist-art-alice-s-kandell.

[35] Id.

[36] International Campaign for Tibet. Nepal prevents Dalai Lama birthday celebrations in Kathmandu, further undermining Tibetans’ rights, July 9, 2019, https://savetibet.org/nepal-prevents-dalai-lama-birthday-celebrations-in-kathmandu-further-undermining-tibetans-rights/

[37] International Campaign for Tibet. Nepal: Government denies rights of Tibetan refugees in UN review, July 8, 2021, https://savetibet.org/?s=Nepal%3A+Government+denies+rights+of+Tibetan+refugees+in+UN+review

[38] Id.

[39]International Campaign for Tibet. Nepal prevents Dalai Lama birthday celebrations in Kathmandu, further undermining Tibetans’ rights, July 9, 2019, https://savetibet.org/nepal-prevents-dalai-lama-birthday-celebrations-in-kathmandu-further-undermining-tibetans-rights/

[40] United States Department of State, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, Nepal 2022 Human Rights Report, https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/415610_NEPAL-2022-HUMAN-RIGHTS-REPORT.pdf, 11, 13-17.

[41] Jon Krakauer, Why is Nepal Cracking Down on Tibetan Refugees? The New Yorker, December 28, 2011.

[42] Id.

[43] Supra fn 39.

Three saddhus seated at temple on Kathmandu's Durbar Square, Nepal, performing the vitarka mudrā. Photo Markus Koljonen, May 10, 2008, CCA-SA 3.0.

Three saddhus seated at temple on Kathmandu's Durbar Square, Nepal, performing the vitarka mudrā. Photo Markus Koljonen, May 10, 2008, CCA-SA 3.0.