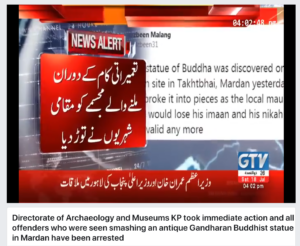

A widely disseminated video posted on Twitter showing construction workers smashing a large Buddhist statue with sledgehammers has raised serious concerns about the treatment of antiquities, especially pre-Islamic antiquities in Pakistan. The builders encountered the massive stone statue while excavating earth for the foundations of a house being built in Mardan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. The construction workers who smashed the Buddhist statue filmed themselves destroying the ‘idol.’ The contractor was ostensibly told by a local cleric that he would “lose his imaan (faith) and his nikah (marriage) will also not remain valid any more.”

Screenshot, Dr. Abdul Samad Twitter feed.

Dr Abdul Samad, the recently reappointed Director Archaeology and Museums, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, appeared on television on July 18 to say that the authorities had located where the destruction had taken place and that the construction workers would be identified and arrested soon.

Many Pakistani citizens have appreciation for ancient pre-Islamic monuments, especially those who live in areas of the country where Buddhism and Buddhist iconography and sculpture once were prevalent. Others are ignorant of the historical importance and heritage such finds represent. Unfortunately, there are strongly held beliefs in much of the population that merely allowing Buddhist monuments to exist is contrary to the teachings of Islam. For centuries, it has been considered a positive act to behead or destroy pre-Islamic statuary, resulting in thousands of ancient objects being smashed, decapitated, and most recently, blown up by the Taliban.

Regrettably, Pakistan has devoted little funding to preservation of monuments, construction of museums, or public education on Pakistan’s early history. Ancient objects are generally regarded as objects of interest only to outsiders, and more have been preserved in the 20th and 21st century because they were seen as valuable objects for sale than because they represented an educational resource for society.

As CPN noted in a 2017 report, the authorities’ indifference to the historical value of ancient art has often resulted in damage and destruction of Pakistan’s heritage.

Gandharan Buddhist head in trash heap at National Museum, Karachi. Photo Athar Khan, Express Tribune, November 17, 2017.

In 2017, one of Pakistan’s most important museums made headlines after Gandharan period stone statues were discovered in a rubbish pile, visible from the street, at the National Museum in Karachi, Pakistan. The statues, from the 3rd-5th century, had been seized in a 2012 raid on a smuggling ring in 2012 in the Awami Colony in Karachi five years before. Two of the five statues were used to decorate the doorway of the antiquities director-general’s personal office, the others were tossed into a rubbish heap outside. There was no information available on the fate of the other 330 “rare objects” recovered in the Awami Colony raid.

National Museum director Mohammad Shah told the press, “We believe this sculpture dates back 1,500 years and it will be given an original look when we wash it.” Questioned by Hafeez Tunio in The Express Tribune, the director said, “We have put these sculptures over there ourselves.” He claimed that they were naturally protected from the elements by the black schist stone they were constructed from.

Tunio wrote:

“Unfortunately, these sculptures are facing the same fate as hundreds of other artefacts and dozens of archaeological and heritage sites, which are in an absolute shambles due to the archaeology and antiquities department’s neglect.”

Gandharan sculptures lying in trash heap at National Museum, Karachi. Photo Athar Khan, Express Tribune, November 17, 2017.

A National Museum employee, who requested anonymity, said that the treatment of the Buddhist statues highlights the general neglect of antiquities and cultural heritage sites rampant under the archeology and antiquities departments of Pakistan. Many other artifacts have been neglected and improperly stored. The employee elaborated, “no one has looked after them for years and many are now rusted and stained. I cannot tell you how pitiful the condition of the rare objects inside the museum is.”

It seems that the items supposed to be housed in the National Museum were lucky even to make it to the museum’s garbage pile. Other seized antiquities from 2012 were smashed while in police custody. There, according to the Express Tribune, sweating laborers argued whether the items were Hindu or Buddhist, ignoring the fact that their rough handling was breaking them:

“The work, which began at about 8am turned the Awami Colony police station into a mangled museum of Gandhara art of over 30 pieces. “We’ll open a museum right here,” joked one of the police officers. “Here, you want to take one home?”

An earlier CPN article, The Dolorous Case of Pakistan’s Museums, April 8, 2016, noted that:

“Despite the hard work of a small number of dedicated academics and archeologists, museums and ancient monuments in Pakistan are generally as moribund as cemeteries for art and artifacts. Pakistan’s cultural institutions have also been victims of the cupidity of several generations of corrupt officialdom. In March 2016, the anti-corruption department in Peshawar announced that it was launching an investigation into the replacement of original sculptures and coins from the Peshawar Museum by fakes.”

However, visiting foreign experts have long held that a number of important Buddhist sculptures in the Peshawar museum had already been replaced by fakes in the 1970s and 1980s.

Neglect within Pakistan’s government museums is an even greater concern than rampant theft. In July 2015, artifacts from the Moenjodaro and Mehrgarh civilizations at the archaeology department in Karachi were dumped into open boxes awaiting transport to the National Museum. According to Pakistan’s national newspaper Dawn, archaeologists were alarmed by the abrupt transfer of archaeological collections and a valuable library of rare books to the National Museum:

“There were boxes lying on the dusty floor. It looked like as if someone had packed them in haste. If there were artefacts in the cartons in which products of daily use are normally kept, it’s a terrible mistake because experts believe that the department is in possession of objet d’art and other articles dating back to ancient times.

The boxes were lying in the middle of a large room that looked like a badly kept library. It is not. The books are no less valuable than the artefacts. According to the person who was at the branch at the time and did not wish to be named, the books belonged to the federal government. In one corner, one could see broken pieces of pottery. It seems they are part of the materials found by local and foreign archaeologists over the course of their excavations and got damaged while being removed to be transferred to another site.”

Screenshot, Dr. Abdul Samad Twitter feed.

Screenshot, Dr. Abdul Samad Twitter feed.