Briton Sentenced to 15 Years in Iraqi Jail for Smuggling Antiquities is Released

Ruins of the North Palace of the Neo-Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II at the ancient city of Babylon, Iraq. 6th century BC. 30 January 2012, Author Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg). CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

In June, a fifteen-year sentence for smuggling antiquities was handed down in a court in Baghdad. James Fitton, a British national, was arrested at the airport when small pottery shards were found in his bag. His companion, Volker Waldmann, was likewise arrested but was released without trial. The court’s decision shocked not only Fitton’s family and his lawyer, but also the international community. The law under which Fitton was sentenced dates to the Saddam era, and is intended to prosecute thefts of cultural objects of archaeological or monetary value, not fragments of the kind Fitton was charged with stealing.

Fitton’s legal representative appealed the ruling on the grounds that Fitton took only miniscule and valueless shards, which he found in an unguarded site, and picked up without knowledge of the illegality of his actions. The fact that Fitton made no effort to conceal the shards in his luggage was also raised as evidence of his lack of criminal intent.

Soud’s argument was successful, and the sentence was overturned last week. Fitton will likely soon be freed to return home, much to the relief of his family, having been detained in prison since his arrest on March 20th. The case drew considerable international attention to Iraq’s apparently arbitrary enforcement of its cultural property laws. Despite the overturn of his disproportionately severe sentence, news of Fitton’s experience may have a chilling effect on Iraqi tourism, which is only slowly rebounding after the past decade of turbulence, especially as the country relies on Iraq’s historical sites to attract visitors.

Yale University Artifacts Seized by Manhattan DA

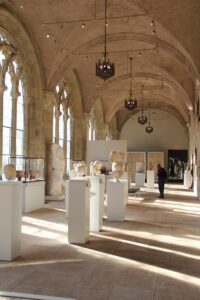

Sculpture Hall of the Old Art Gallery of Yale University Art Gallery after 2013 renovation, exhibiting Greek & Roman statuary. Photo by Nick Allen, 8 March 2014, CCA-SA 3.0 Unported license.

This Spring, the Yale University Art Gallery, in cooperation with the Manhattan District Attorney’s office, relinquished twelve art works from its collection. The Yale Gallery was made aware of the object’s illegal provenance as the result of long-running investigations by the New York District Attorney’s office into the criminal activities of several antiques dealers in that city. Nine of the Yale objects had been purchased from Subhash Kapoor, a Manhattan-based dealer in South Asian art who was the object of a nine-year investigation by the DA, dubbed ‘Operation Hidden Idol,’ which concluded in 2019. Kapoor was charged with theft and smuggling in India in 2011, where he awaits trial, and a probable subsequent extradition to the USA to face further charges. Kapoor sold the nine artifacts in question to the non-profit Rubin-Ladd Foundation, which subsequently donated them to the Yale University Art Gallery

Two more of the objects handed over to investigators by Yale were previously sold by Doris and Nancy Wiener, New York antiquities dealers with close ties to Kapoor. Doris Wiener passed away in 2011; in 2021, her daughter Nancy was charged with conspiracy and possessing stolen property, and pled guilty.

The DA’s office was assisted in the identification of the stolen objects by the India Pride Project, an online group of anti-art-trafficking activists focused on securing the restitution of stolen objects pertaining to Indian culture.

The Yale University Art Gallery, like all museums, places a high value on responsible and ethical collecting. To support that cause, a full list of objects in the Yale collection whose provenance is uncertain or incomplete is available on their website, and at the AAMD’s Object Registry. Research into these objects’ provenance is an ongoing part of the Gallery’s work as responsible caretakers and art educators.

Ethiopian Jewish Family Rescues Manuscript

Abandoned Synagogue with Painted Stars of David – Wolleka (Falasha Jewish Village) – Outside Gondar – Ethiopia. 28 April 2013, Photo Adam Jones from Kelowna, BC, Canada. CCA-SA 2.0 Generic license.

Thirty years ago, an Ethiopian Jewish family fled their hometown for Israel. They left as part of the Israeli airlift of Ethiopian Jews from Addis Ababa in response to persecution by the Ethiopian government and the outbreak of civil war. They left in the night, and in secrecy, circumstances that forced them to leave behind one of their family’s most treasured possessions: a parchment book of psalms, written in Ge’ez, an ancient Semitic language used by Ethiopian Jewish clergy, and annotated in red ink by a kes, or rabbi. The book is a priceless artifact of the religious traditions of a Jewish community that now largely exists in diaspora.

The family left the book in safe-keeping with non-Jewish neighbors, but never forgot it. For years, they were unable to retrieve the book, which had fallen into the hands of a Christian priest, who demanded that they pay a steep ransom for its return.

Having received information that the priest had been arrested, and was in immediate need of money, three members of the family flew to Ethiopia to negotiate with him. Ultimately, they paid the priest $1,200 to surrender the book.

Now, it is back with their family in Israel. It is a priceless survival of a fading tradition, for very few people today can read the language it is written in. The family plans to restore the fragile book, in the hope that it will serve as an anchor for the Ethiopian Jewish community in Israel.

Carabinieri Seize $2M Artemisia Gentileschi Painting

Artemisia Gentileschi’s Roman Charity, which Italian officials say was illegally exported.

Carabinieri Cultural Heritage Protection Squad via AP.

A painting by the seventeenth-century painter Artemisia Gentileschi, Caritas Romana, was recently seized by Italian cultural police from an Austrian auction house. Dorotheum, which had not yet offered the painting for auction, has papers showing that the painting was legally exported in 2019, but the Carabinieri Command for the Protection of Cultural Heritage disputes that claim. At issue is whether the painting’s value and cultural significance were significantly understated at the time of export.

Prior to its seizure, the painting had been caught up in a legal battle for some years, since the export license was revoked in 2020, after the painting had left Italy. It is now in Bari, Italy, in the keeping of the Italian government.

Italy’s cultural patrimony laws are intended to prevent the export of works important to Italian history and culture. Artemisia Gentileschi was not only a master Italian artist of her period, but also one who has enjoyed increasing fame in recent years. Her art often reflected on themes of gender violence and the suffering of women; in her own life, Gentileschi was a rape survivor who faced court-ordered torture in her attempt to seek justice for the crime. Works by Gentileschi now hang in many of the world’s greatest museums. If the Italian government succeeds in prosecuting its current owners, Caritas Romana will become property of the nation, and will likely go on display in a museum in its home country.

Statue of Kubera, formerly in Yale University Art Gallery, photo courtesy Manhattan District Attorney's Office.

Statue of Kubera, formerly in Yale University Art Gallery, photo courtesy Manhattan District Attorney's Office.