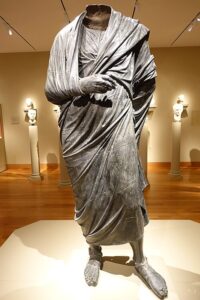

Statue of an Unknown Philosopher, photo by Gordon Makryllos, 11 May 2017, Cleveland Museum of Art, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

The Cleveland Museum of Art announced in February 2025 that it would return one of its most famous artworks, a larger than life-sized, headless bronze statue, to the Republic of Turkey. The statue was long thought to represent a Roman emperor but is now identified as a Greek philosopher. In the last five years, there have been numerous claims by the Turkish government that major bronze sculptures that have been in U.S. museums for decades were taken illegally from the site of Bubon in ancient Lycia in southwestern Turkey, where an acropolis, a theater and a Sebasteion, a shrine dedicated to the Roman Imperial cult, were located.

The Sebasteion at Bubon, built by the Emperor Nero in the first half of the 1st century CE, was a monumental complex erected by local elites to honor the Roman emperors. It once featured a series of bronze statues atop stone pedestals, which remained buried for 1800 years, until villagers began uncovering them in the 1960s. According to recent investigations and interviews, the villagers sold the statues to a dealer in Izmir, where they were funneled to a dealer known as ‘American Bob’, now identified by prosecutors as antiquities dealer Robert Hecht. The villagers who sold the bronzes appear to have kept their find secret from government officials for decades. Meanwhile, the bronzes were given false histories and fed into the international art market, making their way into major museums and private collections.

Portrait head of Drusus Minor, returned by Cleveland Museum of Art to Italy in 2017 when identified as having been stolen in 1944. Photo Cleveland Museum of Art.

The statue had been on display at the Cleveland Museum of Art since 1986, the most celebrated artwork in its classical Greek and Roman collection. However, it was the extensive scientific testing by the museum that provided compelling evidence linking the statue to the ancient site of Bubon.

A 2022 article by Colgate University’s Professor Elizabeth Marlowe in Hyperallergic is credited with “renewing interest in the Bubon statues with Turkish authorities.” They in turn contacted the Manhattan District Attorney’s Antiquities Trafficking Unit (ATU). The ATU then began a years-long pursuit of statues from Bubon in U.S. collections. Wary of the ATU’s well-known tactics of seizing antiquities first and only rarely asking questions afterward, the Cleveland Museum of Art took steps to ensure that the museum would be able to determine for itself if there was justification – and solid evidence for the return.

It should be said that Cleveland did not take lightly the claim that the sculpture had been taken illicitly from Bubon. The Cleveland Museum has a history of returning ancient artworks to their countries of origin upon uncovering evidence of illicit activity. In this case, the museum argued that there was insufficient evidence for Turkey’s claim and that the New York District Attorney had failed to show that the museum did not have rightful and legal ownership of the artwork.

The museum asked the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Ohio, Eastern Division, to declare it the statue’s rightful owner. In response, the Manhattan DA announced that it was preparing legal papers to fight for its custody and return it to Turkey. But until the scientific analysis and pending return was announced, Cleveland held on to the statue. Only after it was completed did the museum end its legal claim.

The process of investigating an artwork’s history can be simple – or take decades to unravel through scholarship. Scientific study, provenance research and public transparency are now key elements of museum operations. The investigation by the Cleveland Museum validated the maxim that a museum is the best place to discover the truth about an object or to uncover a checkered history.

Scientific Analysis Reveals Statue’s Origins

The main entrance of the 1916 wing of the Cleveland Museum of Art, photo by Zenbikescience, 23 April 2013, CCA 2.0 generic license.

At the heart of the museum’s decision to return the statue was a multi-faceted scientific analysis, involving advanced materials testing, soil analysis, and 3D modeling. A breakthrough came from studying the statue’s feet, which include a preserved lead plug in the left foot. Researchers made molds of the feet and compared them to stone pedestals still in situ at Bubon’s Sebasteion sanctuary, where similar holes once anchored bronze statues.

To strengthen the case, photogrammetric 3D models were created of both the statue and the pedestal blocks, allowing precise digital comparisons. These visual matches were supported by lead isotope analysis, which showed that the lead plug in the statue’s foot chemically matched lead residues from a Bubon pedestal.

In a third line of inquiry, scientists conducted soil analysis, comparing sediment found within the statue to soil samples taken from three locations at Bubon, as well as from another statue known to have originated at the site. The mineral signatures aligned, reinforcing the conclusion that the Philosopher had once stood at Bubon’s Sebasteion.

Together, these independent lines of evidence—physical fit, elemental analysis, and geochemical consistency—enabled the museum to conclude that the statue had almost certainly been unearthed at Bubon.

Cleveland Museum of Art, 14 August 2021, photo by Erik Drost, CC by 2.0 license.

The new evidence also led to a reassessment of the statue’s identity. Originally believed to be a representation of Emperor Marcus Aurelius—whose name appears on a separate inscribed base at the Sebasteion—the statue is now more likely a generic representation of a Greek philosopher. The pedestal to which the statue appears to match bears no identifying inscription.

So far, 15 artifacts taken from the Bubon site, now worth tens of millions of dollars, have been repatriated from museums and private collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Fordham University.

As a result of its scientific findings, the Cleveland Museum not only withdrew its legal claim to ownership but is working cooperatively with Turkish authorities. Discussions are underway about the possibility of a temporary exhibition of the statue in Cleveland before its final return, as part of a broader initiative for cultural exchange.

In announcing the return, the museum stated: “The museum appreciates the cooperation of Turkish officials and the Manhattan D.A.’s office in resolving this matter through rigorous scientific research… Without these investigations, we would not have been able to determine with confidence the statue’s true origins.”

Cleveland Museum of Art, 26 April 2015, photo by Erik Drost, CC by 2.0 license.

Cleveland Museum of Art, 26 April 2015, photo by Erik Drost, CC by 2.0 license.