More than 60 years after a 15th century sculpture disappeared from a temple in Southern India, an independent scholar (who has chosen to remain anonymous) has located it in the holdings of the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford. The scholar discovered that the Ashmolean’s sculpture was identical to one in a 1957 photograph in the archives of the Institut Français de Pondicherry and the Ecole Française d’Extrême-Orient (IFP-EFEO) showing the statue in the temple of Sri Soundarrajaperumal, near Kumbakonam in Tamil Nadu province. Neither local worshippers, nor Indian officials, nor the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) had reported that the original statue had been removed or that a substitute was left in its place.

The 60cm tall bronze statue depicts Tirumankai Alvar (also known as Thirumangai Mannan). Tirumankai Alvar was a saint-poet and a devout Vaishnava who discouraged Shaivism, Buddhism, and the Jain religion. He was the most recent of the twelve Alvar saints of southern India, and is believed by religious adherents to have lived around 2700 BC. Modern scholars date his life to 7th-8th century CE. Tirumankai Alvar is thought to have been a military commander, a chieftain and a reformed robber.

Kumbakonam ramasamykovil கும்பகோணம் இராமசுவாமி கோயில், Festival in Kumbakonam, Author பா.ஜம்புலிங்கம், 9 September 2015, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, Wikimedia Commons.

Ashmolean officials contacted the Indian government, which determined that the statue presently in the temple was indeed a copy. On February 14, Rahul Nangare, the First Secretary of the Indian High Commission in London, thanked the Ashmolean Museum and Oxford officials for their work in investigating the provenance of the statue and issued a formal request for its restitution.

The Ashmolean Museum had purchased the statue in 1967 from Sotheby’s auction house. The Art Newspaper reports that it had been sold for £850. The seller was a Dr. J.R. Belmont of Basel Switzerland, who was known to have an exceptional collection of Indian sculpture.

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, photo by Lewis Clarke / Oxford : Ashmolean Museum / CC BY-SA 2.0

The Oxford University museum has stated that it will work with the scholar who discovered the link to the Indian temple to clarify the object’s history. A spokesperson for the Ashmolean stated that if on further investigation the statue’s provenance is questionable, it will work with the Indian government to return the object. Since Indian authorities were completely unaware of the substitution for 60 years, it may be challenging to determine the facts of the supposed theft.

To many, it may seem obvious that the sculpture was stolen. But a glance at a very famous temple theft of approximately the same period shows that there are other possibilities in which local collusion, the sub rosa granting of an export permit, or other factors may be present. The example is merely illustrative of the fact that there may be more to the story of the Ashmolean statue than is now apparent. It is incumbent on the museum to thoroughly research its provenance in order to find out as much of the truth as possible before taking any other steps.

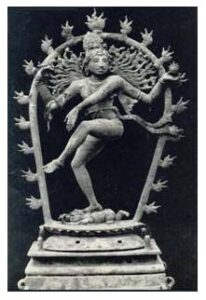

An Example: The Norton Simon Sivapuram Nataraja

The Indian government made its first repatriation claim against a foreign-held object, a large and beautiful bronze sculpture of Siva as Lord of the Dance, known as the Sivapuram Nataraja, in the 1970s. In 1951, this statue had been found together with five others in a farmer’s field in Thanjavur district, Tamil Nadu. Although legally, the statue was government property under India’s Treasure Act, the statue was placed in custody of the nearby Sivagurunathaswamy temple. Five years later, several individuals conspired to send the statues to an Indian restorer who made copies which were returned to the temple while the originals were sold. The authentic Sivapuram Nataraja was sold first to collector Lance Dane in Bombay, and then passed into the well-known Indian private collection of Boman Behram in Bangalore. In 1969, Behram sold the statue to New York art dealer and collector Ben Heller. Heller sold the Nataraja to California businessman and philanthropist Norton Simon in 1972 for $900,000 for his new museum in Pasadena, California.

Sivapuram-Nataraja, bronze, Norton Simon Foundation.

Meanwhile, in 1965, British Museum curator Douglas Eric Barrett had inspected the sculptures in the Sivagurunathaswamy temple and informed academic colleagues that the sculptures stored there were fakes. Although the Sivapuram Nataraja sculpture was generally known to be in the Norton Simon Foundation collection, it was only as a result of publicity surrounding a major exhibition at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of the Norton Simon Foundation’s Indian art collection in 1973 that Indian authorities became aware that the Nataraja was in the U.S.

Soon after, the Indian government claimed the sculpture and asked for its restitution, at the same time filing civil lawsuits against the Norton Simon Foundation and Ben Heller in California and New York. India claimed that the statue was exported by means of false statements and in knowing violation of Indian law. The Foundation argued that the statue had been legally imported into the U.S. and that the Indian government had abandoned its interest, having been able to discover the statue’s whereabouts for years and taking no steps to recover it while it was displayed notoriously as part of the Boman Behram collection.

The case was resolved through an out of court settlement. The Norton Simon Foundation agreed to recognize India’s ownership and return the statue to India. India agreed to allow the statue to be displayed in the Norton Simon Museum for ten years, and gave the Foundation carte blanche to purchase any Indian antiquity already outside of India with complete immunity from suit for a period of one year.

Does the Ashmolean Statue have such a complex chain of custody? Was it actually stolen, or was it sold from the temple? It may not be possible to determine what really happened at this late date, but the actions or inaction of Indian officials or widely-exploited loopholes in Indian law at the time could be relevant to a decision to keep or to return the statue. Only a thorough investigation can begin to answer those questions.

Indian laws over time

Indian newspapers and bloggers and the archaeological press have reported the discovery of the Ashmolean statue as yet another case of ‘colonial’ abuse, theft and smuggling. They blame Western collectors and museums for taking precious and inalienable Indian heritage from the country. However, the situation is more complex than it sounds. While India has had laws on the books since the 19th century restricting the export of monuments and specific antiquities, at certain times these laws allowed for the payment of a fine in lieu of having an export license, or granted minor officials leeway to issue permits. The dates on which events took place make a difference. Certainly, there is evidence that during the first half of the 20th century, if not for longer, Indian laws regarding restrictions on export of antiquities were honored mostly in the breach. It is incumbent on the Ashmolean Museum and representatives of the Indian government to work together to research the provenance of the sculpture.

Temple in Kumbakoman, Author Devsasi, 24 August 2011, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license, Wikimedia Commons.

For example, the Ancient Monuments Preservation Act (Act No. VII of 1904) did not nationalize ownership of antiquities. If antiquities were sold or exported “to the detriment of India or any other country,” the government could prohibit export by publishing a notice in the official Gazette of India. Sculptures, carvings, bas-reliefs or similar items in danger of being moved or damaged could be subject to compulsory purchase by government authorities at a fair market price. However, the right of government authorities to compulsory purchase did not extend to any religious object currently in use, or to anything which the owner reasonably desired that was personal to himself or his family. The 1904 Act was never officially repealed.

The Antiquities Export Control Act, 1947 (Act No. XXXI of 1947) and its Rules regulated the export of antiquities, which were “any article, object or thing declared by the Central Government by notification in the Official Gazette to be an antiquity for the purposes of this Act, which has been in existence for not less than one hundred years. After the 1947 Act, a Customs officer would no longer have discretion to impose a fine in lieu of seizure or confiscation. Only the Central Government could do so.

But it was only after the Antiquities and Art Treasures Act 1972, which came into force on April 5, 1976, that the Indian government explicitly claimed control over movable cultural property consisting of antiquities and art treasures. The Act regulated the export trade, prevented smuggling and fraudulent dealings in antiquities, and enabled the compulsory acquisition of antiquities and art treasures for preservation in public places. This Act was supplemented with the Antiquities and Art Treasure Rules 1973, also in effect from April 5, 1976, and repealed 1947 Antiquities Export Control Act.

The Ashmolean’s statue of Tirumankai Alvar may indeed have been stolen and smuggled out of India. If it was, then it is accepted museum practice in Europe or the United States to return objects when there is evidence that they are stolen. It is to be hoped that the statue, if returned, would actually go back to the town and temple from which it was taken. It has not been Indian government practice to return icons to their original temples. Other returned objects have simply been stored in warehouses and neither placed in museums nor returned to their original owners. More and more ancient sculptures from extant temples are being removed from them and placed in ‘icon centers’ where bronze disease is rampant and their fates have been uncertain. As more objects are returned from Western collections, thanks to the diligent research of museums and independent scholars, it is hoped that India will devote its energies toward developing cultural property practices better attuned to current Indian social and educational needs and to religious practice.

In the case of the sculpture of Tirumankai Alvar, as in many others involving Indian artworks, it was a researcher who did the work to identify the object, and a museum that stepped forward to report the possibility of theft, not the Indian government. The sale of the statue at Sotheby’s from a known Swiss collection was documented and therefore traceable. What has never been documented are the literally hundreds of thousands of Indian temples and monuments from which such objects were removed both legally and illegally under Indian laws dating back to the mid-nineteenth century.

Indian government commissions established by its national legislature, have been by far the harshest critics of India’s Ministry of Culture for its failure to enforce its own regulations, provide adequate staffing, account for funding, document thousands of objects, or to update in any way the system of care for Indian heritage which has not changed since the early 20th century. It is as a result of these failures, detailed in government reports such as the Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India on Performance Audit of Preservation and Conservation of Monuments and Antiquities (Report No 18 of 2013), that India has never photographed or even counted the objects that are supposed to be under its care. Following the recommendations in these government reports to improve documentation, conservation, and public access to India’s cultural heritage would enrich it far more than the return of any icon.

Statue of the saint Tirumankau Alvar, 15th c., bronze, Ashmolean Museum, copyright Oxford University/Ashmolean Museum.

Statue of the saint Tirumankau Alvar, 15th c., bronze, Ashmolean Museum, copyright Oxford University/Ashmolean Museum.